A few years back we were on a trip to New Zealand, where I had been asked to give three lectures at a conference in Auckland. We had decided it was pointless for me to fly there alone and straight back, so we arranged a tour encompassing Dunedin, Queenstown, the west coast of South Island, a drive across to Christchurch (I got a speeding ticket then), a flight to Wellington and a drive to Napier before returning to Auckland.

While in Queenstown we arranged a trip to Milford Sound in a small plane. I loved it. My wife did not, not helped by our homestay owner asking jocularly as we set off for the airport whether we had made our wills. I had promised my wife a larger plane than the six-seater we had. The scenery as we crossed the mountains was amazing and as it turned out the pilot had been a barman in one of our local pubs in England. After we had landed, he said we had been lucky as the weather forecast the next day was for cloud, so he would not be flying. My wife asked why not. “Well,” he said, “you can never tell whether a cloud might have a hard centre.”

That’s a long anecdote to illustrate a principle. The principle is – if you don’t know, perhaps you should not take a chance. Clouds can hide mountaintops. But in medicine there are many ‘don’t knows’, and while it might be acceptable to judge the risk-benefit on an individual basis it may not be appropriate to apply a blanket approach for an entire population.

Of course, if you don’t know that there is a risk you might construe that as being that there is no risk. But if you don’t know, well, you don’t know. And what if someone raises the possibility of a risk? Would you still plough on regardless, or would you wait until you knew for certain?

There’s an Arab proverb: “He who knows not, and knows not he knows not, he is a fool — shun him; he who knows not, and knows he knows not, he is simple — teach him; he who knows, and knows not he knows, he is asleep — wake him; he who knows, and knows he knows, he is wise — follow him.” My father added another two: “He who knows not, and knows that he knows, is dangerous – avoid him. But he who knows, and knows that he knows not, he is wiser still – take heed, for he has true understanding”.

I would like to think I am one of those last.

I posted a response to an online essay as follows – it was in response to one of the growing number of analyses of Covid vaccine risks:

One thing bothers me, and always has – with this and all other disputed items [the issues of Covid and climate change have become interweaved]. If the so-called vaccine deniers who have done careful analyses of available data like this are wrong, why are these analyses not properly and scientifically debunked? All we get is bluster, very occasionally quoting improperly conducted trials. There is of course a good reason they are not debunked, and that is because they are correct. Am I wrong?

This concern is especially important right now as there are official mutterings about the worry of a coronavirus resurgence and the need for booster vaccinations. But there are many unknowns. What is the real risk of post-Covid vaccination myocarditis? What are the potential risks of DNA contamination of mRNA vaccines? Could the introduction of plasmids cause short or long-term changes within cells that have substantial and perhaps frightening consequences?

The answer is, we don’t know. Maybe, but maybe not. The research has not been done (or if it has the results have not been revealed). Given the potential risk, particularly the long-term risk of incorporating foreign DNA into cell nuclei, would it not be wise to suspend vaccination programmes until we do know?

Consider Maryanne Demasi’s interview with Phillip Buckhaults, a cancer genomics expert at the University of South Carolina. Initially fearing that a report by another expert, Kevin McKernan, on the risk of DNA contamination was “conspiracy” he decided to debunk the work, only to find out that his own investigation confirmed it. In a remarkably balanced and non-polemical set of answers he makes the point that there may be risks – but we don’t know whether there are, what they are and, if so, how big they are. He suggests:

It’s possible that long bits of DNA that encode spike are modifying the genomes of just a few cells that make up the myocardium and cause long term expression of spike… and then the immune system starts attacking those cells… and that’s what’s causing these heart attacks. Now, that is entirely a theoretical concern. But it’s not crazy and it’s reasonable to check.

Frankly, there’s an awful lot of concern. It needs to be allayed.

The above principle of ‘don’t know, don’t do’ also applies to climate change. There is undoubtedly climate change and there always has been. Is what we are seeing now due to human activity? I think some of it is, but it may pale into insignificance compared to the effects of sunspot activity, volcanic eruptions and other natural processes and I suspect that the contribution of fossil fuel use may be less important than deforestation and water diversion (see Brazilian rainforest and Himalayas for examples of the first, and the shrinking of the Aral Sea for the second).

Does an increase in CO2 actually matter? Probably not, as it will aid plant growth. Is the global warming trend as steep as is being made out? Probably not, as temperature measurements are distorted by changes in the local environment of sensors (for example, by becoming more urbanised, or in the most egregious case of the U.K.’s hottest day ever in 2020 possibly being caused, extremely short-term, by jet aircraft roaring past the sensor with their afterburners going).

Most of the ‘need for change’ is driven by modelling, so is no more than prophesy, not least if the models have garbage going in, for then garbage will come out. Many people have raised serious and credible concerns on this and pointed to the reality of observational data which contradicts the prophesies. Even in the here and now, contrary to the dire predictions, Great Barrier Reef coral bleaching has reversed, Antarctic warming and ice loss is occurring over the top of active underwater volcanos, and the biggest greenhouse gas problem likely came from the Tonga volcanic eruption which threw vast quantities of water vapour into the high atmosphere. I have yet to see any serious and credible counterargument explaining why the sceptics who state these facts are wrong. If there were such arguments, surely they would and should have been deployed. That they have not lends credence to the accuracy of the sceptics’ views and makes one wonder whether the whole climate crisis is just an artificial one that has somehow turned into a kind of cult.

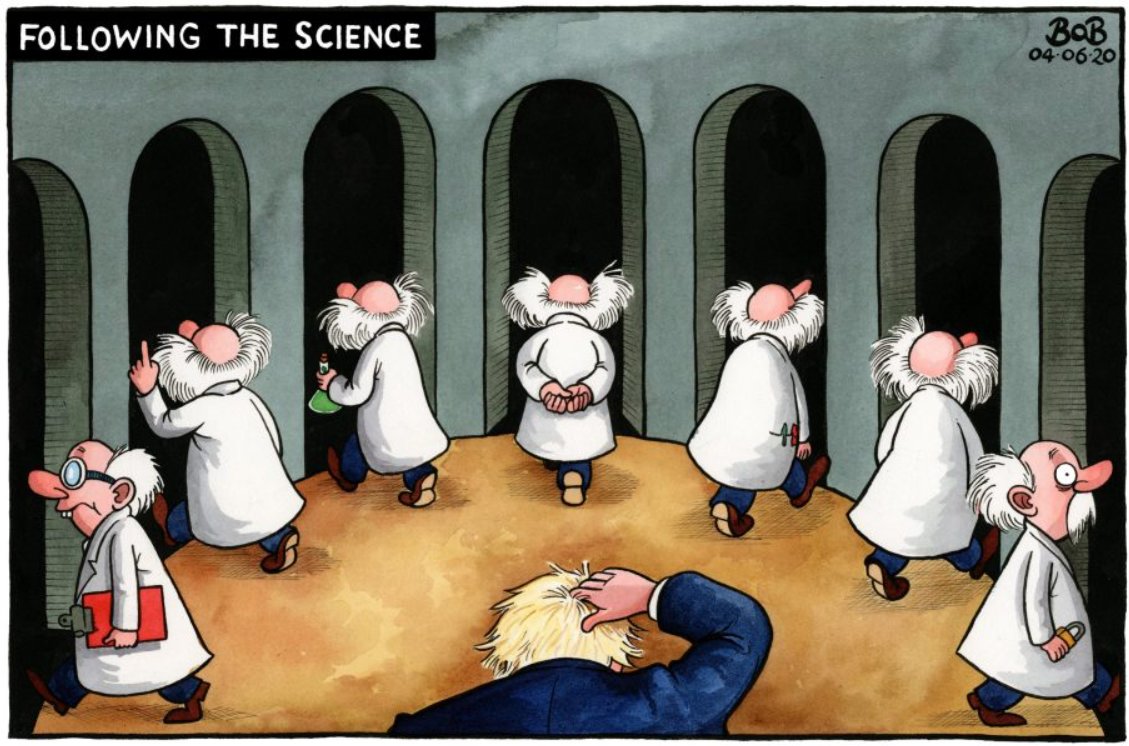

If the major drivers of climate change are natural phenomena we are only fiddling with the fringe. And that’s before we examine the practical question: is Net Zero economically feasible? Is the overall cost of going electric higher than the cost of the status quo? Can we go all-electric with vehicles when there are insufficient charging points and the demand on the National Grid will be unmanageable? I fear our politicians and some of our scientists are people who know not and know not that they know not. Maybe some are beginning to grasp reality, but the rest are, as in the proverb, fools. Some are in the know not, but know that they know group, and are dangerous. If we don’t know, let’s not do until we do know, and meanwhile beware of false prophets.

I am not alone in thinking this. Earlier this week Dr. David Seedhouse posted a piece on the Daily Sceptic, which he concludes by saying:

We are constantly bombarded with unanalysed assumptions, often presented to us by people with obvious vested interests. Some years ago there was a variety of ways to challenge these assumptions. For example, decent journalists in serious publications would do this and these challenges would filter into the public consciousness. But this seems to happen less and less in the mainstream, where ‘experts’ are presented as authoritative voices on X or Y simply because they say they are, or have a prestigious title, and it is impossible to challenge them directly.

The failure to think deeply, the abandonment of reason, the rush to the preferred conclusion, the desire – even the need these days – to go along with the majority view without questioning it – these are symptoms of a cultural descent into myth, superstition and collective madness. The truth is what we want it to be and what our ‘experts’ say it is and that’s all you need to know.

I submit that this abject thoughtlessness – not ‘the climate crisis’ – is the real ‘test of our times’.

Hear, hear.

Dr. Andrew Bamji is a retired consultant rheumatologist.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.