How do you get people to take pharmacological action against something that hits them on average once a year and lasts a few days, like acute respiratory infections? They have been around since creation and are extremely familiar to everyone around the globe, including animals.

Acute respiratory infections manifest themselves with a range of symptoms – from none all the way to pneumonia and death from respiratory failure. Thankfully this happens only in a small minority of cases.

To sell, you have to have a market, but familiarity breeds contempt. So you have to create a market for your products, be they medicines, opinions, careers, research funds or whatever.

One approach is to confuse a syndrome with a disease. This means using the F-Word ‘flu’, a terrible Anglo-Saxon colloquialism which is used all over the world, even by WHO and the U.S. CDC. Using the F-word, you are bundling up familiar signs and symptoms, fever, ache and pains, tiredness, cough and runny nose due to numerous but uncountable microorganisms (a syndrome) and implying that it is due to a single agent (influenza).

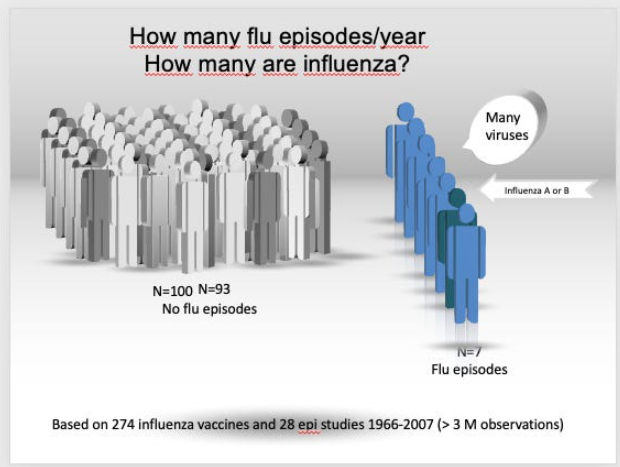

In a pie study, we did nearly 20 years ago, we showed that based on three million observations in an average year, only one out of nine F-word episodes are due to influenza.

When ministers blame winter crises on ‘flu’, we do not really know what they are talking about (neither do they), but they do have a solution: vaccines and antivirals. That is because, up until very recently, influenza was the only seasonal respiratory agent for which licensed pharmaceuticals (antivirals) or biologics (vaccines) were available. Now the tune has changed, they blame it on ‘Flu and Covid‘ (F- and C- words), but it’s just an update of the same manipulation.

Politically this is a helpful strategy. Because instead of admitting there is little that can be done to minimise the impact of the seasonal F-word and the ‘new’ C-word, you can be seen to be doing something like railing about low vaccine uptakes or putting pressure on pharma to produce more antivirals.

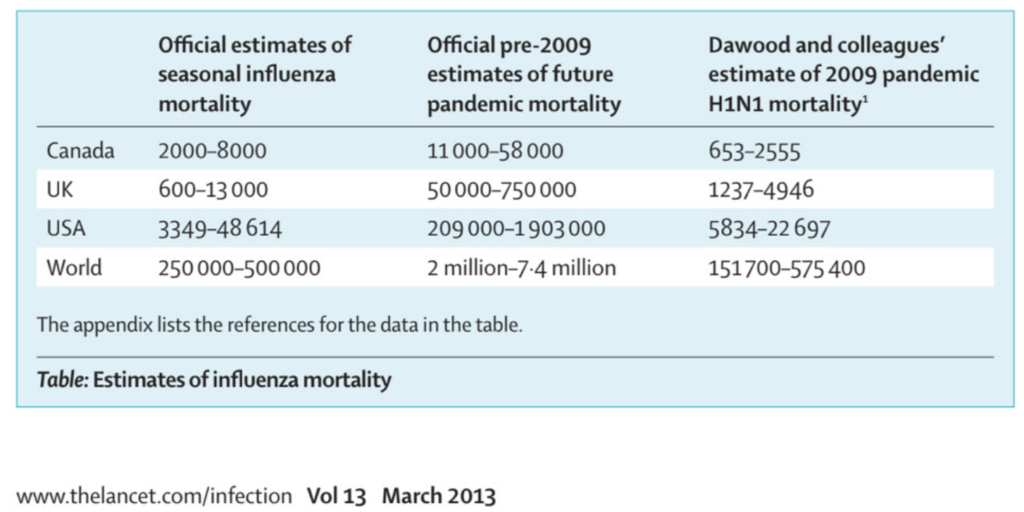

A second approach is to frighten everyone into thinking that the yearly death tally for the F-word (influenza) is a lot higher than what is verifiable and that the next pandemic is around the corner.

You do need the media’s help to frighten everyone, but you can always find editors to oblige.

Some media may be owned at least in part by pharma, which makes life a lot easier to get your message across.

We have seen this approach in detail with Covid and the yearly F-word ‘flu’ for at least fifty years. How do you inflate deaths? That’s easy! You start with taking the bundle ‘influenza and pneumonia’ on a death certificate as a true, verified fact. We have explained just how imprecise this method is. For example, in the U.K., in 2015, there were three verifiable influenza deaths per million inhabitants, rising to roughly 24 per million in 2018. Is this a health crisis? Hardly enough to justify doing much. This is why incidentally, influenza vaccines and antiviral trials show an absence of evidence on death prevention: the outcome is too rare even for a large trial.

The next step is to ask modellers to forecast deaths either in what you will call interpandemic or in intrapandemic years.

In going back to models, note the use of the two terms (interpandemic and intrapandemic), which subtly introduced the concept of the inevitability of a pandemic. “It’s just a question of time.”

A third approach is to appoint those who most benefit from creating fear to run or inform your Government of ‘protection measures’, as pointed out by Philip Alcabes at the dawn of the 2009 influenza pandemic:

We are supposed to be prepared for a pandemic of some kind of influenza because the flu watchers, the people who make a living out of studying the virus and who need to attract continued grant funding to keep studying it, must persuade the funding agencies of the urgency of fighting a coming plague.

This is why the worst-case scenario is always presented.

A further approach is to create a cartel of key opinion leaders apparently hugely knowledgeable and capable of giving advice even on newly identified agents. This is the case for the European Working Group on Influenza (or ESWI), which is funded by pharma companies and has been hugely successful in influencing opinion and even policymaking. Many of the ESWI member names recur in our series on antivirals.

Keith Duddlestone pointed us to a further refinement: adding ‘community groups’ to the chorus of voices building pressure. Patient involvement is an old marketing technique, but continuous funding by the industry points to their importance in creating demand.

Then you should present your product as the pharmacological equivalent to a Gucci bag or Rolex watch, a designer drug tailored and produced to keep the monster at bay. Yes, such articles exist, written by people who should have known better because they have a long history of doing good work in this area.

Linked to this is the other approach to turn funders and industrialists into saviours. This happens time and time again when politicians are running out of fig leaves – we will publish three of the contracts that states stipulated with vaccine manufacturers in the run-up to the 2009 influenza pandemic.

We would be very surprised if the model had changed during the last pandemic.

Last but not least, you can change definitions such as ‘pandemic’ to fit what is going on rather than the other way around. This way, the facts always fit the definition, and you can keep everyone on their toes and provide the magic button to be pressed to activate sleeping contracts and emergency laws: it’s a pandemic! Panic stations.

Here is a rather blatant example: the 2009 influenza pandemic was nowhere as severe as the marketeers forecast, so they needed to change a few things, better if done without creating too much fuss.

Manipulation apart, the WHO ‘pandemic preparedness’ page shows a further and now discredited equation: that ‘pandemic’ means influenza. In the end, the most perceptive observer of the many transformations, Peter Doshi, concluded that there is no universal definition of an (influenza) pandemic.

So are we sleepwalking into something much worse than the last three years if the WHO is true to form?

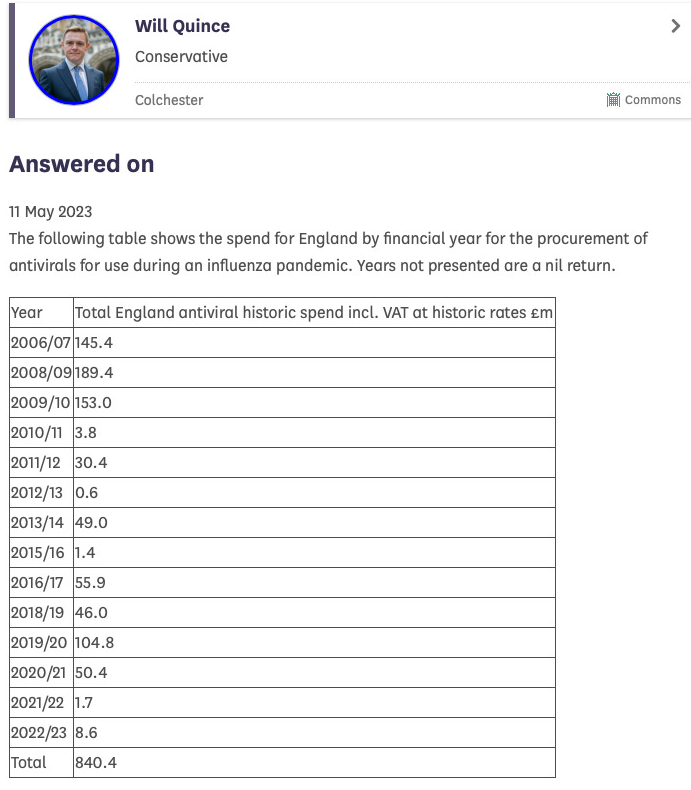

But make no mistake: the creation of the market for antivirals has been hugely successful, as a reply to a Parliamentary question shows:

Pandemics are good for the business model of antivirals: £840 million spent so far. Not a bad return for ‘modestly’ performing drugs!

Dr. Carl Heneghan is the Oxford Professor of Evidence Based Medicine and Dr. Tom Jefferson is an epidemiologist based in Rome who works with Professor Heneghan on the Cochrane Collaboration. This article was first published on their Substack blog, Trust The Evidence, which you can subscribe to here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Indeed. $cientism, Church of. Word salads. Fraudulent models with poor coding and corrupt data sources. Meaningless junk output. A priesthood who inspect the junk models and entrails and who offer their divine interpretation. Chosen Apostles. The lurgy and Gospels. Heretics burnt. Children and the old sacrificed to Moloch. All for profits. No science, just $cientism the merger of government, tech and data into a religion.

Steve Kirsch on substack is asking anyone, anywhere, for a single study on any stab effectiveness, ever. He is offering money. No takers, no offers, because no proof has ever existed. Ever. Ask your local quack or vet for one they have no clue.

But as the article says, scamdemics, made-up virus scariant stories and stocking the kitchens of brain dead hypochondriacs is good for business and profits. Why else is the Tranny fascism so ardently pursued? Pharma makes U$1 mn per mentally ill midget who thinks his johnson is a vagina. Rona produced some £40 billion in profits it is estimated. Yet the sheeple idiots can’t figure any of this out.

Bit surprised they didn’t mention the hated PCR mass testing as I would have thought that tool alone was integral to manufacturing a faux Covid pandemic. It’s how they tried to trick us that flu had mysteriously disappeared for the first time since the dawn of time anyway. And we all know that the flu jabs are just money-making bollocks but here’s one observational study looking at 14 years of data anyway. Their conclusion matches that of a recent big Japanese study looking at the efficacy of flu jabs featured on Dr McCullough’s substack.

”Results: The data included 170 million episodes of care and 7.6 million deaths. Turning 65 was associated with a statistically and clinically significant increase in rate of seasonal influenza vaccination. However, no evidence indicated that vaccination reduced hospitalizations or mortality among elderly persons. The estimates were precise enough to rule out results from many previous studies.

Conclusion: Current vaccination strategies prioritizing elderly persons may be less effective than believed at reducing serious morbidity and mortality in this population, which suggests that supplementary strategies may be necessary.”

https://sci-hub.se/10.7326/M19-3075

I’ve mentioned elsewhere that my Mum (who, unlike me, is on Facebook) saw a post some moron did where he Lateral Flow tested himself five times in one day. The fifth test was positive. ‘Just goes to show you can’t be too careful!’ said the self-righteous jerk, who was likely looking forward to two weeks leave paid for by the likes of me!

All it said to me was that he got a false positive using a crappy test that didn’t even look for COVID-19.

I’ve prided myself on never having taken a single test, never wearing a mask and never having a jab.

I recall they covered mass testing in another post

They have been getting angrier and closer to explicit denouncement of the jabs

I guess they thought that reason would prevail and now realise it won’t

What if the PCR was not just inaccurate but 0% accurate?

The philosopher Karl Popper gave the Black Swan explanation as a way to show that a scientific theory was false.

He said that if the scientific theory was that all swans were white then we could spend an eternity counting white swans but we would only need to find ONE black swan to show that the theory was false.

For PCR the theory is that PCR can detect illness.

However there was a PCR Black Swan event that occured at the Dartmouth Hitchcock medical centre Whooping Cough outbreak in 2006 where the PCR was proved to be 0% accurate at detecting Whooping Cough. To make matters worse, Whooping Cough is a bacteria and logically much easier to calibrate the PCR to detect it and yet, in this instance, it failed.

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/22/health/22whoop.html

If it can’t detect a bacteria then how can it detect a virus, an entity orders of magnitude smaller than a virus?

The theory that Covid is an imaginary virus that exists only in the mind, remains extremely plausible.

Christ, this is depressing. Is anyone in the Stamford region who can verify this? I was hoping it was fake news ( or perhaps they were queuing for an art exhibition! ) and people were getting wise to the toxic shots but it looks like the brain-dead Covidian force is strong in this neighbourhood. 🙁

”People are queuing around the block at Stamford Arts Centre for covid jabs.

The booster vaccinations are being offered to those over 75 today (Friday, May 12) on a first come, first served basis.

On Wednesday, the drop-in session closed after just two hours when the centre ran out of the 140 jabs that were available.”

https://www.stamfordmercury.co.uk/news/people-queuing-around-block-for-covid-19-booster-jabs-9312358/

There’s a very popular drug called Paracetamol whose exact mechanism of action is – to this day – entirely unknown. Some people claim it works for them, some other people claim it doesn’t. Some experts claim to be convinced that it works. Some other experts believe that – if it has any effect – this must be a placebo effect. The only thing that’s really certain about it is that it kills people and that the number of people killed increase with increasing dosage. It’s available over the counter everywhere and the NHS recommends it (together with Ibuprofen) as universal medicine against everything (Take paracetamol and wait until it’s over). Because of this, people buy it and take it.

COVID shots are a currently more fashionable medicine of the same kind and you even get to see a real medical practioner, quite a rare experiences these days. Why wouldn’t people queue for getting them? At least, there’s a silver lining to this cloud. We’ve gone from Get needled or else … ! Survival of mandkind depends on it! to 140 members of a so-called high risk group can get a free shot here (and the others may then go home again).

That’s an implicit admission that COVID really isn’t dangerous, not even for people supposed to be especially at risk because of it.

I lived in Stamford for 14 years and now not that far away. Know the Art Centre well and they are clearly queuing for the hall at the back, which makes sense for a jabathon. For an art exhibition you’d go in at the front and head down to the right. So, I’m afraid the walking dead clearly abide in Stamford. Has a population of well over 20,000, though, so not quite so bad, perhaps

I live 12 miles away.

My ex used to live in Stamford but moved to Oakham because she regarded the middle class people of Stamford as charmless thick snobs.

Divorce forced us to leave, but I occasionally return for the meal out with my now grown up kids. Was in a Turkish restaurant on Thursday celebrating my son’s 18th and staring up at me from the “wait to be seated” table was the execrable, “Stamford Living”, a magazine so loaded with self-satisfied middle class mediocrity and self-congratulation that it could almost be satire at first glance. Thank heavens it wasn’t dropping on my door mat during lockdown – I dread to think of what sanctimonious drivel it would have been promoting.

A friend of my Mum’s has just had her SIXTH jab!! She won’t believe that there’s anything wrong with them, saying it’s ‘antivaxxers’ making things up, even though my Mum’s heart was severely damaged when she had a third jab (my Mum’s never having another one!)

My parents (both in the first half of their eighties) stopped after the third because my mum (generally a common-sense person but generally trusts in authorities as well) came to the conclusion that people had been sticking needles in her arm for enough times now. They’ve also both had COVID before, in between and afterwards.

Damned idiots.

A lot of people are wondering if a new pandemic/plandemic emerges would there be as much compliance. I would say yes, although a bit smaller, but this isn’t really the important thing. More important is how well-organised and well-glavanised the resistance would be in such a situation and it really would be locked and loaded. And this force is more like a fart in the wind in that it just puts it out there and waits for attention. I understand why people fear the recurrence of this pseudoevent but I think world events are about to intervene in such a way that this will seem like some schoolboy prank from long ago. If you don’t covet your own life or the lives of your loved ones then everything changes. He who loves his life shall lose it, what more is there to be said?

Well, let’s hope not. Maybe there will be a degree of (psychological) immunity to it the next time round. We are doing out best to achieve that.

The real worry for us and the prize for govts and industry is mandatory vaccination.

They had to do it for a number of reasons. If you recall just before it was announced Trump killed Iranian General Soleimani. The whole economic situation was about to go into freefall. I don’t excuse their actions but to give them their due there was simply no other option and at least it delayed the suffering for a few years more. At this point in time we no longer have that luxury,. We don’t have anything to bargain with or sell. We grow up taking for granted international trade and we forget that it is a serious matter if it dries up.This situation requires huge and raidcal action on the scale of the agreement after the last war.

Another great summary. Does flu (or whatever you choose to call one of the bugs giving you respiratory symptoms) matter? Mostly no. 99.5% no. Forget the antivirals that mostly don’t work. Even forget the vaccines because they don’t seem to stop bug acquisition, but if you don’t get very ill so what? Concentrate on the 0.5% who get really sick. Work out who might get very sick and why. Sort out the testing to identify them before they get too sick, and apply the correct treatment. Oh, I forgot. I said this already. In May 2020. If it doesn’t make you ill it doesn’t signify.

I do not understand why supposedly clever scientists cannot grasp this, nor why, despite my urging, they have not read the textbook explaining it all (which came out in 2019).

It is difficult getting a scientist to understand something when his funding stream depends on not understanding.

The secret is to NEVER believe anything the government tell you and everything will be just fine. Bunch of Handkrankers

A Pandemic Manufactured by lies

************************************

Stand in the Park Make friends & keep sane

Sundays 10.30am to 11.30am

Elms Field

near play area

Wokingham RG40 2FE

I’m extremely embarrassed to admit that I don’t understand the mechanism of how drugging people to the eyeballs benefits the government.

The revenue flows from treasury to pharma, as I understand it, so where do the kickbacks happen?

I can understand how a pandemic benefits HMG by facilitating power grabs and more legislation but how do they gain financially?

Other steps:

This has been a masterful plan.