Back in March of last year, I pointed out that Covid’s impact on mortality had been small relative to pre-existing differences across Europe. In other words: increases in mortality within European countries were smaller than the differences that existed between them before Covid arrived.

At the time, I relied on a crude measure of mortality: number of deaths per 100 people aged 65+. We can now observe the same pattern using the latest data on life expectancy.

Life expectancy in a particular year is defined as the number of years a person born in that year could be expected to live if he or she experienced the current age-specific mortality rates (at each age 0, 1, 2, etc.) during the course of her life. It is therefore closely related to the age-standardised mortality rate.

Both statistics take into account the ages of those who died, as well as the age-structure of the overall population. Hence they’re ideal for comparing across countries and over time. The only advantage of life expectancy is that it’s easier to interpret: talking about the number of years someone can expect to live makes more sense than talking about a standardised rate of something.

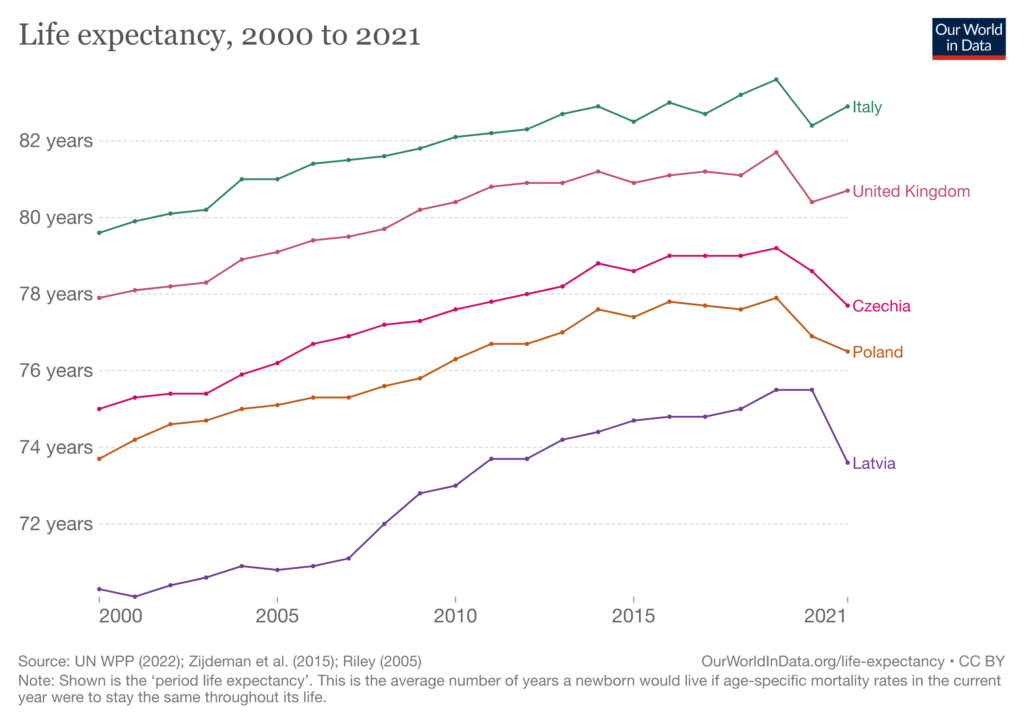

Consider the chart below, which show life expectancy in selected European countries from 2000 to 2021.

Of the countries shown, Latvia saw the largest decline in life expectancy of around two years. (That’s using 2019 as the baseline. If we used the average of 2015–2019 as the baseline, the decline would be somewhat less than two years.)

Is this a large amount? In terms of year-on-year changes, yes. Latvia hadn’t seen such a big decline since the fall of the Soviet Union. But in terms of pre-existing differences across Europe, not really. In 2019, Italy’s life expectancy was 8 years higher than Latvia’s. So in a normal year, Latvia experiences four pandemics worth of mortality, relative to Italy.

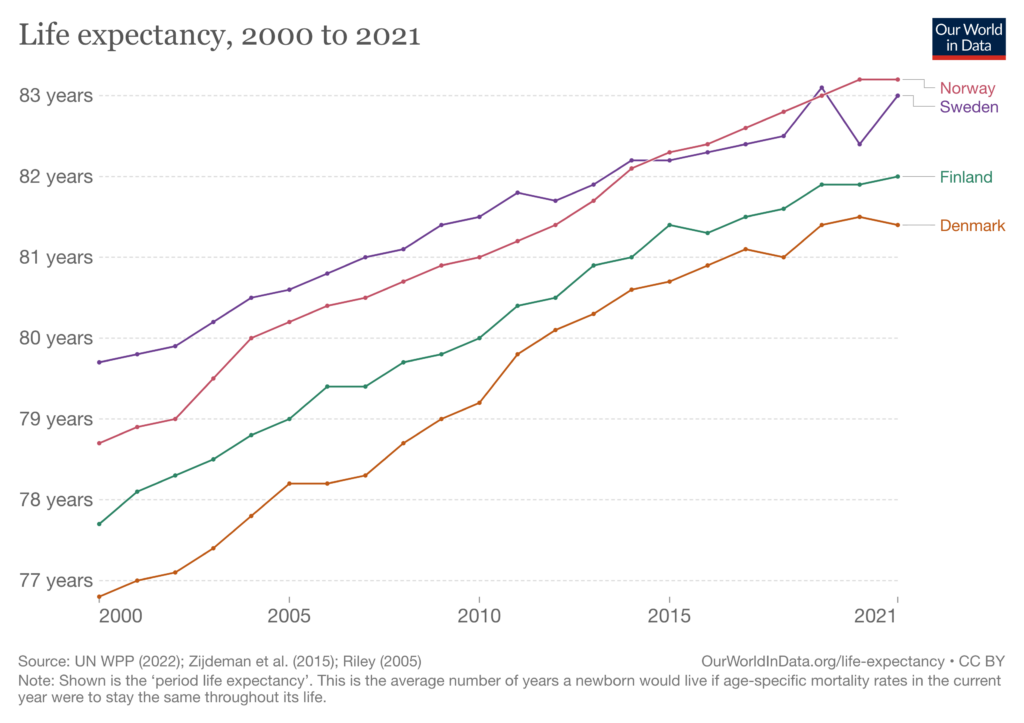

We can also compare Sweden to the other Nordic countries, as in the chart below. The first thing to notice is that even in 2020, when Swedes supposedly faced “disaster”, they actually lived longer than both Danes and Finns. At the height of the pandemic, Swedish life expectancy was 82.4, compared to ‘only’ 81.5 in Denmark.

The next thing to notice is that although Swedish life expectancy did fall in 2020, that was largely because it had risen the year before (which led to the build up of ‘dry tinder’). As you can see, Swedish life expectancy in 2020 was approximately the same as in 2018 – an unremarkable year when no one spoke of “disaster”.

If you smoothed-out the rise and subsequent dip in Sweden’s life expectancy, its trajectory would look similar to that of other the Nordic countries – contrary to the oft-heard claim that Sweden was an outlier among its peers.

Of course, the declines in life expectancy would have been larger if we’d done nothing in response to Covid. But the point is: there are already much greater differences across European countries, and these haven’t caused anything like the reaction we saw to Covid. Which would suggest that we overreacted.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

“Of course, the declines in life expectancy would have been larger if we’d done nothing in response to Covid.”

I am not absolutely sure I agree with this, and do not think the “of course” prefix is justified. And the comparison drawn implies that we had two options – do what “we” did or do nothing – whereas we could have done something in between, like Sweden or the Great Barrington Declaration.

We know there are things “we” did in response to Covid which probably reduced life expectancy – such as mass vaccination using mRNA injections or cancelling cancer screenings or generally limiting or deterring access to the NHS or rejecting the use of alternative treatments for Covid (such as HCQ or IVM) or putting patients on ventilators … etc

If we’d done nothing – and particularly not rolled out the injections – I am not at all convinced that natural immunity following infection and recovery for most people would not have been better in terms of life expectancy. And the as-yet unrecognised (officially, at least) harms to life expectancy through the impact of the injections would also have been avoided.

I agree. I’ve never seen any compelling evidence that any of the covid responses were helpful

There is no evidence that lockdowns, masks, reduced Covid deaths prior to vaccination, and given the months it took to double-dose large sectors of the population in 2021 most of whom not at risk of death from CoVid, there is no evidence that ‘vaccination’ reduced the death rate.

However. Isn’t it also the case that there was a significant increase in non-CoVid deaths at home and later in hospital due to failure of seriously ill people either seeking or getting prompt medical attention for treatable diseases?

The people most likely to die of CoVid were going to die anyway of something else most likely within the next 12 months. CoVid just advanced their death. But those dying at home/hospital for lack of medical care died prematurely, as have those killed by the mRNA experimental dosing.

Had we done nothing, or the third option of targeted care and vaccination, many of those non-CoVid deaths would not have happened

So we might say, ‘of course’ had we done nothing life expectancy would be little affected.

Steve Kirsch has an interesting piece on cause of death in the USA since 2020 which shines a light on the medical interventions for covid treatment & injection.

https://stevekirsch.substack.com/p/now-everyone-can-easily-prove-the

I’m not sure if this is replication, but it’s an interesting article & raises questions about the role of adult RSV infections in the jabbed adult cohort & the increase in paediatric RSV cases around the world.

IMMUNE TOLERANCE

The trainwreck of all trainwrecks: Billions of people stuck with a broken immune response

“The massive surge in RSV that Western nations are seeing, is a consequence of vaccinated adults now beginning to tolerate RSV, thus leading to a jump in infections in children, as they’re exposed to it more often.

With children now getting these infections from vaccinated adults rather than from other children, the infectious dose they receive will tend to be higher. This could be sufficient to explain the higher virulence observed in children.”

https://www.rintrah.nl/the-trainwreck-of-all-trainwrecks-billions-of-people-stuck-with-a-broken-immune-response/

I suspect China will make an interesting case study. Within a couple of months the majority of the population will have had some brush with covid. As a proportion of normal fatalities there’ll be barely a blip.