Up until April of 2020, the basic case for lockdown was still intact: there’s a virus going round with a 1% mortality rate; it will continue spreading until two thirds of the population has been infected; if we don’t lock down, hundreds of thousands of people will die; therefore we must do so.

Now, I’m not saying this case was strong. After all, it completely ignores the issue of civil liberties – even if locking down had saved hundreds of thousands of lives, doing so might have still been wrong given the massive constraint on freedom it entailed. Another weakness is it assumes the only way to stop people dying was by locking down; in reality, we could have tried focussed protection.

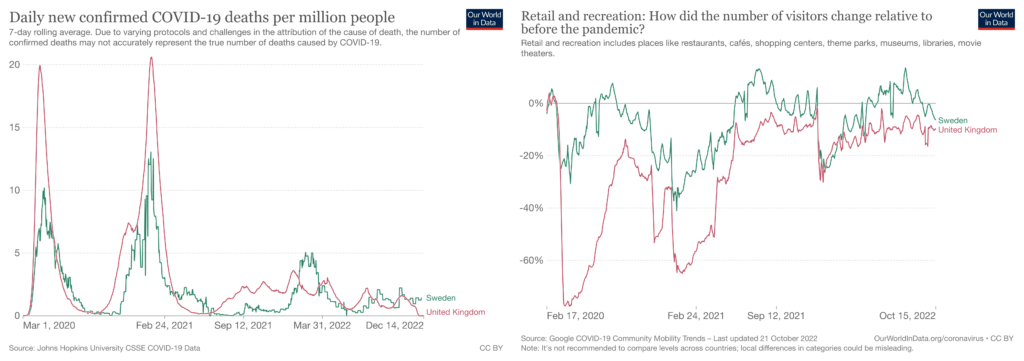

Nonetheless, the premises at least appeared sound. This changed at the end of April 2020, when Covid deaths in Sweden began trending downward (left-hand chart below).

Aside from closing high schools and banning large gatherings, Sweden did almost nothing to halt the spread of the virus. There was no stay-at-home order, and no forced business closures. Despite this, daily deaths began falling at exactly the same time as in Britain – which had gone into lockdown at the end of March.

It’s often claimed that Swedes locked down voluntarily by drastically reducing their time spent outside. But this simply isn’t true, as Google mobility data shows (right-hand chart above). Swedes reduced their time spent on retail and recreation by only a quarter as much as Brits.

Sweden’s experience clearly undermined the second premise in the case for lockdown: that Covid will continue spreading until most people have been infected. After Sweden, it was no longer possible to argue that lockdown was necessary to halt the spread. You could still argue it made a difference, but not that it was the only thing standing between us and armageddon.

Which raises the question: why did so many people continue calling for lockdown? Why didn’t it dawn on them that the cost/benefit ratio was much greater than they’d initially believed? And I’m not just talking about joe public, who massively overestimated the risk of dying. Many ‘experts’ who were perfectly aware that the risk was low continued banging the lockdown drum.

Three reasons come to mind.

First, the benefits are concentrated (on those who are protected), whereas the costs are widely dispersed. Second, the benefits are immediate, whereas the costs are largely delayed (inflation, government debt, worse educational outcomes). Third, measuring the benefits is easy (or at least, was presented as being easy), while measuring the costs is somewhat harder.

For these reasons, I suspect, the costs were more difficult for people to “see” – in the sense of Frédéric Bastiat’s essay ‘What is seen, and what is not seen’. It’s not just the magnitude of costs that affects decision-making, but also their ‘visibility’.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

I remember perfectly what happened.

When it became clear that it wasn’t that dangerous the authorities insisted on pretending it was much more dangerous than it was. And it made sure the truth was suppressed and only their message got out.

That’s what happened.

.

March 19th 2020: Covid19 is declassified as a High Consequence Infectious Disease

March 23rd: Lockdown starts…

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/high-consequence-infectious-diseases-hcid#status-of-covid-19

And that right then and there should have been the end of the debate. And lockdowns should have been completely off the table from day one.

Of course, another reason why it was downgraded could have been so the government would not be required to provide early treatment and prophylaxis (HCQ, IVM, Pulmicort, various vitamins, etc.). Because if they did, that would have taken the wind out of the sails for the jabs.

Many understand this to be the primary reason, as the vaccines would be hugely profitable and the known therapeutics (IVM, HCQ, VitD, etc.) not. Always follow the money.

Not this rubbish again. A HCID classification requires specialist measures including treatment in dedicated facilities, by specially trained staff. It is used for the quarantine and treatment of Ebola cases and suchlike.

Once Covid began spreading widely it was clear that it would not be possible to send all infected persons to the limited amount of specialist facilities we have available. There is no smoking guns in the downgrading of Covid, it was simply a reflection on the infectiousness and trajectory of infections at the time.

BINGO. If it was really anywhere near as bad as they said, they wouldn’t have to tell anybody twice. They would instead be trying their darnedest to calm everyone down.

There’s a much simpler explanation – that it was never about public health.

nail on head

BINGO. It’s all about power and control.

Regarding the second reason, one of the major long term costs is quite likely to be reduced life expectancy, or not to put too fine a point on it, death. A graph showing excess deaths might be useful. In effect, the whole idea will be proven to be contradictory in the long run.

Of course, there will have been other reasons, such as financial benefits to certain organisations, e.g. the pharmaceutical trade. The declaration of Emergency Use Authrorization (EUA) will have been a bonanza for that lot. No shortage of opportunism either.

joe public was barraged by round the clock covid propaganda from the government and big pharma. the majority of politicians as well as ‘experts’ even those who were doubtful about lockdowns decided to play along for the fear of being hanged (literally or metaphorically) by the angry mob. There were also ‘experts’ funded by the pharma and Gates from whom it was pointless to expect anything but compliance.

I wonder what would have happened if in 2020 there was something else in the news. A war or something so that the joe public would switch channels when covidian clowns from SAGE were presenting their models and scare graphs.

Why?

1-They were told to. UK Totalitarians under that idiot Johnson and the SAGE Communists spent £500 million on endless propaganda. The Sheeple were sufficiently terrified. It was all planned (Event 201, endless patents stretching back 10 years, countless confabs and international coordination).

2-But even beyond the propaganda the real issue is that the Sheeple pray to the $cience. Fascism just has to invoke that religious narrative and wheel out the idiots in white jackets with models. $cience is now the secular religion of choice. If the $cience says LDs work but only if you eat Dog Shit 3 x a day and inject poisoned junk you can’t pronounce or name, the Sheeple will comply. Their religion, rituals, rites, obeisance demands it.

“Up until April of 2020, the basic case for lockdown was still intact”

No it wasn’t. Diamond Princess. And of course the knowledge that “lockdowns” were useless, which was orthodoxy before the CCP went mad.

“For these reasons, I suspect, the costs were more difficult for people to “see” ”

No they were not. I did some calculations on the back of a postage stamp and it was obvious the cost benefit analysis could never stand up, even without including a cost for lost liberty.

And the USS Theodore Roosevelt as well.

And the Charles de Gaulle.

That is 3 ships with contained populations showing the differences in age susceptibility.

Research was published and largely ignored from all 3 episodes.

Let’s not forget the ‘outraged’ reaction to the Great Barrington Declaration by all the “Experts” hand picked by our Beloved Leaders.

Add in the fact that lots of people thought lockdowns were great. Still being paid (most Public “Servants”), or paid at 80% (the furloughed) and not having to do a tap of work.

Several I know were off in their cars, for long walks. Only the unlucky got shouted at by drones.

I seem to remember that one of the big arguments about where the ‘pandemic’ was going after the first ‘wave’ was that it wouldn’t come back as ‘viruses don’t do waves’. When it did come back, they called it a ‘ripple’ or some such. So the intellectual heavyweights pronouncing the end of the ‘pandemic’ in Summer 2020 were, in the eyes of the public and many of the decision makers, proven wrong.

However, this picture is greatly distorted by the fact that the second ‘wave’ was quite different from the first as ‘cases’ had by then been redefined as positive test results, rather than hospital presentation with symptoms. Yet the numbers are even now shown side by side as though they represent the same thing. This, in my opinion, was one of the worst deceptions of the whole story, as it enabled lockdown proponents and Professor Ferguson’s modellers to make a superficially plausible case for the continuation of costly NPIs.

And regarding deaths, the definition of a Covid death has been notoriously vague. The second peak shown in the article probably includes all the respiratory deaths that normally occur in winter, as it was impossible to die of a respiratory disease that wasn’t Covid.

Add in the NHS backlog from the lockdowns and then you get a recipe for a very nasty winter of death!

Being run over by a bus also counted, if it was suggested that the victim might have had covid.

It started with deaths, then when the deaths weren’t there, hospitalisations. When those weren’t that bad, it was “infections”. And to make sure there were enough of those, the definition of an infection became a positive PCR test.

They took the lockdown step, they quickly decided on the exit – vaccines (almost certainly pushed by the pharmas and the Gates organisation via the health authorities which they control) – and after that they just stayed the course and came up with whatever justifications and data they needed to justify the plan.

Many were also looking for a significant reduction in that “demon pollutant” CO2 (harmless and essential for all life on Earth).

In that they were disappointed.

But the Psy-Ops Project Fear practice, they adopted wholeheartedly. And are still at it with enormous enthusiasm.

Viruses do waves because each wave only infects a fraction of the population at a time before it trips on itself and crashes, well below the true herd immunity threshold. Rarely is there only one wave for a widespread and highly contagious virus, as it typically takes at least two waves to reach true herd immunity.

First one was about 15% of the population, the second was about 20-25% (cumulative 40% or so), third was another 20% or so (cumulative 60-65% or so), and the various Omicron waves ultimately put the final cumulative total at about 90%+ or so. The final cumulative total would have been probably closer to 50-60% had there not been the virus-magnet jabs and the jab-driven poorly-matched variants.

Ergo, the true mathematical herd immunity threshold (pre-jab and pre-Omicron) was about 40% plus some overshoot above that. Omicron, which is much more contagious, put the threshold at around 80-90% with some overshoot above that as well, not including reinfections that were rare before the poorly-designed jabs ultimately collided with Omicron but have been commonplace ever since.

Regardless, it’s truly endemic now and has been for nearly a year already. The excessive jabs and boosters basically resulted in high endemicity rather than the low endemicity we see in the least-jabbed countries now.

Why did lockdowns continue?

Nothing to do with safeguarding public health and everything to do with control. In other words, pure bloody evil.

Indeed, all about power and control from the get-go.

Four: Paying everyone to stay at home.

What was possibly not to like? (When you’re a moron that is.)

Indeed. (Plays world’s largest hurdy-gurdy, because it sounds like “hurr durr”)

People were manipulated. There were endless posts on all sorts of social media calling for a lockdown, and calling out the government because they hadn’t done so. How many of these posts were genuine? I would say very few. The hard of thinking, which unfortunately seems to be a great many people these days, just followed the herd, and nodded along, with, of course, the carrot of months of ‘holiday’ paid for by the government. The only conclusion I can draw from the whole business is that a lockdown was always the aim, and it was a plan looking for a reason. If covid hadn’t come along they would have thought up something else. B*****ds.

Don’t forget that all the Political Parties in opposition ceaselessly screamed for “Sooner, Harder, Longer”.

Which makes their present moans about the economy and those poor strikers, a trifle hypocritical.

Lockdowns should NEVER have been on the table, period, full stop:

https://brownstone.org/articles/we-need-a-list-thou-shalt-nots-of-public-health/

The biggest question of all: Why no early treatment and prophylaxis (HCQ, IVM, Pulmicort, various vitamins, etc.)? Because if they did, that would have taken the wind out of the sails for the jabs.

Even a focused protection strategy, if one is not careful, can end up making too many concessions to lockdowners. Especially those who exaggerate its effectiveness and ignore or omit early treatment and prophylaxis. The Swiss Doctor was certainly right about that.

Noah’s precise and proportionate analysis is exactly what we need to challenge the public health police state we lived through. Saying things like “we knew that”, and “tell me something i didn’t know”, is as ignorant and thoughtless as any neurotic twitter Covidian. I am sure he will go into more detail on his superb substack but behind these are many nested sub reasons. . What Noah has done is systematically set out three cardinal explanations for what we should call “long lockdown”. I think we can all add further heft to the argument. Mine would be the convenient primacy of behavioural scientists with an authoritarian zeal, and if course the spotlight it gave to mediocre “social control scientists” like Devi Shridhar and Susan Michie.

I don’t know. You could argue as a matter of tactics that it’s good to frame the argument less confrontationally. But personally I am done with backing down or giving people the benefit of the doubt.

“Saying things like “we knew that”,”

Well, we did. Or at least “predicted”. Almost everything that was predicted by nutjob anti-vax granny-killing conspiracy theorists came true.

And interestingly, as El Gato Malo noted some time ago, guess who’s mobility data looks very similar to Sweden’s? NORWAY. Except for maybe one or two weeks where mobility was lower in Norway, they were both pretty similar.

So Norway’s relative stringency was clearly NOT the reason why Norway had far fewer deaths than Sweden during the first wave, or even the second wave either. And in the summer between waves, death rates in both countries were similar despite Norway actually being LESS strict than Sweden for many months in a row. Norway was simply an unusually good outlier for most of the pandemic. Until Omicron, that is, when they got slammed pretty hard overall.

Until Omicron, which came after the mass injections.

True, the jabs were very poorly matched to Omicron, and the resulting herd antigenic fixation (or original antigenic sin) from the jabs then collided with Omicron.

The biggest reason of all was the supposed “moral loophole” of utilitarianism (aka consequentialism):

https://brownstone.org/articles/we-need-a-list-thou-shalt-nots-of-public-health/

Thus, despite the fact that lockdowns clearly flunk any remotely honest cost-benefit analysis, and were thus not part of any Western country’s pandemic playbook, in the absence of strong ethical principles inherently precluding lockdowns outright, the loophole persisted.

That, ladies and gentlemen, is the very root of the problem.

Thanks for the link. I can only recommend the text, despite it’s more food for thought than an answer to anything.

Ultimately, I think what it comes down to is that the vast majority of people are followers not leaders, aka sheep. Even so-called experts. They follow the prevailing wind rather than stick their necks out, and what is more, they convince themselves that they are doing the right thing even when it goes against their natural instincts or professional experience.

From the ever-insightful Dr. Steve Kirsch’s recent Substack article, in a nutshell:

Read that again, and again, and again and let it sink in. Vitamin C, Vitamin D, and Zinc. Those three things alone would have largely defanged and declawed this overall already relatively humdrum virus to begin with, which was basically a classic super-flu at worst, and never an existential threat.

And let’s not forget Quercetin, Thiamine Niacin, NAC, and stuff like that as well.

It seems more obvious that this was all planned, lockdowns included. Too many countries did exactly the same thing, like keeping big box stores open while closing small businesses. The extreme and constant fear propaganda, redefining what a Vax it, declaring emergency powers allowed unfettered government spending, billions unaccounted for, the vilification of opposing medical opinions, the trashing of existing pandemic responses, the arbitrary and baseless covid rules, those in charge ignoring all their covid rules. It’s been the biggest robbery of western countries treasuries in history, If you still believe this wasn’t a planned event, there is not much hope.

Some people during lockdowns enjoyed being paid not to work others liked skiving at home without the need to go into an office and actually do some work. some of these people are now happy to live on benefits with a few cash in hand undisclosed work opportunities and others are refusing to return to their offices. In addition to the many other harms lockdowns caused it has generated a work shy group of people, still getting away with it. We also had an incompetent chancellor who wasn’t adequately flagging up the cost of the money he was dishing out or putting sufficient controls on the massive frauds that were happening. That person has now been undemocratically apointed as our prime minister.