For roughly three hundred years, the Western world – meaning Western Europe and its former colonies – has dominated the world.

The European powers (notably Britain, France and Spain) were dominant from the early 1700s to the early 1900s. And the U.S. has been dominant for most of the 20th century. Western power reached its apogee in the year 1990, with the collapse of the Soviet Union. Two years later, Francis Fukuyama could refer to the “end of history”.

Yet the era of Western hegemony may now be coming to an end.

This is not because the West suffered some obvious strategic defeat. It is simply the inevitable result of population growth and economic development in other parts of the world.

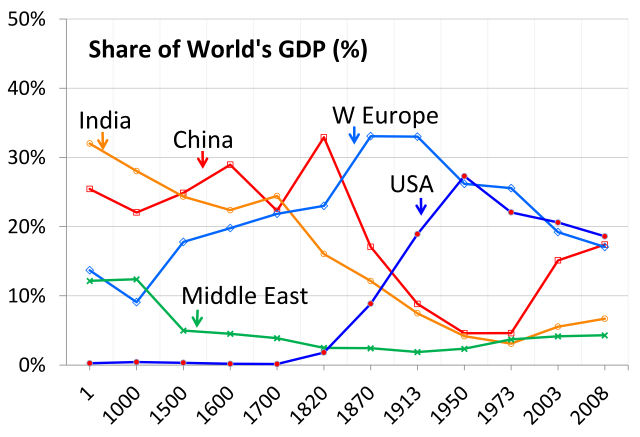

As the populations of non-Western countries have grown, and as their economies have developed, their share of global GDP has risen. In 1990, the West accounted for 60% of global GDP. Over the last two decades, the West’s share has fallen to around 45%. And it will decline further over the next two decades.

Why does this matter?

Although some countries punch above or below their weight, a country’s power can be roughly approximated by its share of global GDP. The U.S. and China have by far the largest economies, and they are the two most powerful. Large economies can afford to spend more on their armed forces, thereby projecting greater military power. They also have more leverage in the economic sphere, where sanctions and trade deals are the tools of statecraft.

Liechtenstein may have the highest standard of living, but it doesn’t get a major say in world affairs because its overall economy is tiny.

This year, challenges to Western hegemony have been more apparent than in any year since the end of the Cold War. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is the most obvious example. But there was also China’s response to Nancy Pelosi’s “provocative” trip to Taiwan, and Iran’s decision to supply Russia with attack drones for use in Ukraine.

Just as revealing as what these three ‘revisionist’ powers have done, is what most other countries around the world have not done, namely sanction Russia. Despite considerable diplomatic pressure from the U.S., they’ve opted to maintain normal economic relations with Moscow.

Meanwhile, the BRICS alliance has sought to expand its membership, as it develops an alternative reserve currency to rival the dollar. And OPEC openly defied the U.S. by announcing oil production cuts at precisely the moment that benefits Russia.

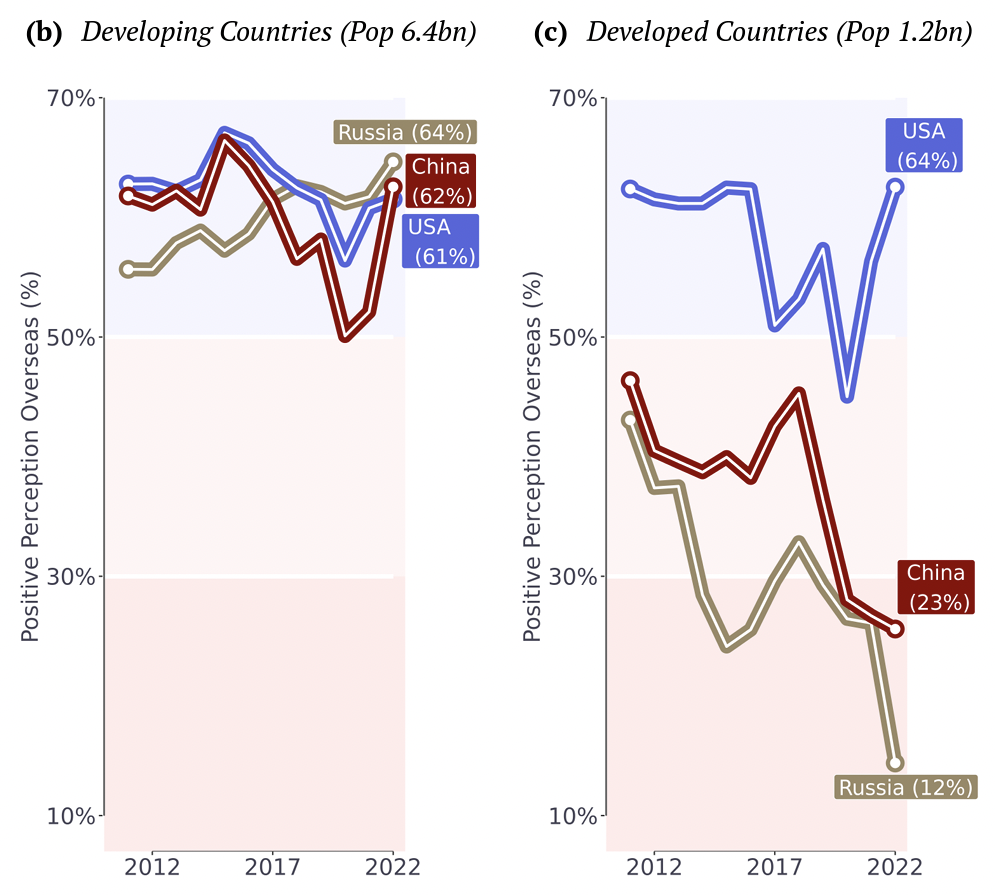

The challenge facing the U.S. and its Western allies is illustrated in a recent report by Roberto Foa and colleagues. Using data from several international surveys, these researchers examined public perceptions of Russia, China and the U.S. in different countries around the world.

Their main finding was as follows. Although most countries have favourable views of the U.S., outside the West most countries also have favourable views of Russia and China. This finding is shown in the chart below.

Developing countries – which account for roughly half of global GDP – view Russia and China just as favourably as the U.S. It is only among developed countries where opinion of Russia and China has grown substantially less favourable.

Given how difficult it proved for the U.S. and its allies to isolate Russia (a declining power), isolating China will be all but impossible. Most countries simply don’t want to pick sides. As China’s economy grows, it will therefore be increasingly able to challenge Western hegemony.

The world, it seems, is returning to multipolarity. And Western countries may just have to live with it.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

It the West retains its current level of hubris with respect to the rest of the world it will continue to lose friends and the decline will speed up.

“And Western countries may just have to live with it.”

Oh we’re doing much better than that – we are actively accelerating our decline through evil and stupidity.

Anyway, I don’t totally buy this. The ability to innovate and commercialise innovation so it is useful is still disproportionately concentrated in the rich world countries. I can see China and India making inroads into that, other regions not so much.

A multi polar world, specifically a world with the US removed as world hegemon is precisely the goal of the globalists. After all what is the point of a world government if the USA, kept to its constitutional framework was able to simply opt out?

The network of trans nationalist oligarchs with their post democratic fiefdoms is the basis for the 1984 like structure of power. The masses will be subject without choice to these totalitarian regimes emiserated by climate policies, sickened by experimental injections, muzzled by hate speech laws and censorship, corralled by travel restrictions and monitored and punished by digital currencies first and international police forces if you dare to protest too much.

Unless we start waking up and rejecting en mass very soon….

..just trying to understand what you are saying. Are you suggesting that the USA is the best hope because it isn’t putting in place all of those things, or putting up some kind of resistance to those things?

Because from where I’m standing they look as though they are as bad as anyone else…if not worse…and a great deal of the ‘globalists’ pit hing these ideas actually originate there?!

I’m suggesting that the US as it was constituted offers the blueprint to counteract tyranny in all its forms. It’s under attack for sure at all levels because it represents the biggest threat to the globalists.

The MAGA Americans have been resisting and there are at least 74 million of them and many are armed.

The globalists are so concerned about them they are willing to throw the country into a second civil war. And yes that is in my mind where the last stand for freedom in the West will happen. The globalist junta that took over illegitimately in 2020 and is again rigging the results in 2022 will do everything they can to grind these people down and force them to react, or red flag them as an excuse to round them up and intimidate them into submission.

I gues we shall see how that goes but things are falling apart so fast they could lose control of the situation.

Just my musings of course.

It depends what you mean by being “dominant”. At the moment, while scribbling this comment, I’m using some kit designed in America, manufactured in China, and no doubt transported by shipping into Southampton or Felixstowe. Some years ago, I worked for an NY registered firm that had an awful lot of employees based in India. No doubt there are many more similar stories from others in a wide variety of industry as well.

FWIW in Clown World, Russia not too bad.

It’s the USA and China that worries me.

Got to hand it to China, helped cause the “pandemic” and will profit from it, to put it mildly.

Conned the BBC/Guardian useful idiots (not too difficult though…).

If the sheep go along with it (and there’s no sign they won’t) they deserve everything they’ll get.

Sadly it would seem they’ll drag us down with them.

Resist.

I think the problem with the West is our adherence to “Human Rights”, which can effectively cripple us, as with illegal migration. We wring our hands at every infraction but are rarely tough enough to do anything about it. Another example is being hamstrung by the EU over N. Ireland. We surround ourselves with a tangle of rules.