With the stock prices of both Credit Suisse and Deutsche Bank under pressure, many in the financial field are becoming concerned the world could be facing a renewed financial crisis. But this time around events could play out very differently. It might not even be banks that pose the greatest financial risk to consumers. It could be payment providers like PayPal.

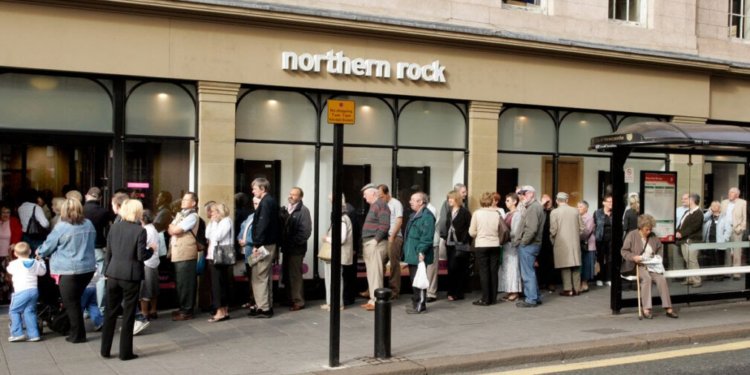

The really big difference between 2007 and 2022 is that bank runs no longer look like the image above, they look like this:

That’s what I was faced with when I tried to transfer £500 from my PayPal account to a regular bank account. On Sunday morning the same message was still occurring. A quick scan of social media proved I was not alone.

“Boycott PayPal” was also trending on Twitter.

So what might the error message indicate about the business?

Here’s what we know so far.

In the last 48 hours a sneaky amendment to PayPal’s acceptable use policy widely captured the public’s attention. Free speech advocates had spotted that customers agreeing to the update would be allowing a sum of $2,500 to be lifted from their accounts if PayPal ever found them guilty of “sending, posting, or publication of any messages, content, or materials” that “promote misinformation” or “present a risk to user safety or wellbeing”.

When word got out, those already concerned about the company’s draconian turn started shutting their accounts and urging others to do the same on social media.

For some, the action proved the final straw.

On Saturday evening U.K. time, PayPal’s former president David Marcus distanced himself very clearly from the action. Elon Musk, whose pathway to billionairehood started in 2000 when his company X.com was merged with Peter Thiel’s Confinity to create the PayPal of today, later tweeted that he agreed.

Readers of the Daily Sceptic and members of the Free Speech Union (such as myself) will already know that over the past few months PayPal has been on a whirlwind tour of shutting down the accounts of platforms and media sites it has deemed guilty of spreading misinformation. In many instances, those affected, such as the Daily Sceptic, were not even consulted ahead of the fact and had little idea of what specific text, post or media had violated PayPal terms.

So why exactly would PayPal descend to this level of reputational self-harm?

It’s hard to know for sure, but chances are the decision rests on pressures PayPal itself is facing with respect to its legal duty to enforce Know-Your-Customer (KYC) and Anti-Money Laundering (AML) rules. If I was to take an educated bet, it’s the counterterrorism section of the rulebook that is most relevant.

These days it’s hard to imagine that banks weren’t always responsible for screening transactions and making judgements about their legitimacy. But until the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) was formed in 1989 with a view to combatting money laundering, banks only really cared about screening credit risk. It wasn’t until 2001 and the 9/11 attacks on the Twin Towers (and the introduction of the Patriot Act) that the scope of banks’ responsibilities in this field was expanded to include combatting the financing of terrorism too.

Tackling terrorist financing and criminality was easy enough when everyone was on the same page about what constituted terrorism or financial crime. But one man’s freedom fighter is another man’s terrorist. And in an increasingly polarised world, it’s become harder for ordinary bank employees to differentiate free-speech critical of authority from radicalising terrorist content, such as that distributed by Isis on social media to recruit new members.

It wasn’t the job they were hired to do.

Three factors have muddied the waters further.

The first is the scale of penalties directed at banks found in breach of AML/KYC regulation. The fear of being slammed with fines has made banks and payment providers like PayPal hugely risk-averse and inclined to err on the side of caution when facing any ambiguity. If something even whiffs of misinformation, from their point of view it’s better to shut it down than to run the risk of getting a fine.

Second, is a lack of resources. Human arbitration is costly, and screening activities would be unaffordable if they were to be done by living, breathing individuals. This is why banks and payment providers like PayPal have invested huge sums of money in cost-saving screening technology to detect illegal transactions both actively and preemptively. The problem here is that most of these tools, known as suptech or regtech, are algorithmically applied with limited human oversight. That means it’s mostly artificial rather than human intelligence deciding who gets to stay on a platform and who gets frozen out. As yet, robots are not well known for their sense of nuance, empathy or capacity to process ambiguity. How they decide what they decide is a black-box interpretation of the inputs they’ve been programmed with.

The third issue is the structure of the KYC/AML policing system itself. Since the scale of the task is so enormous, it goes beyond the scope and capacity of any existing government agency. Knowing this, governments, very similar to how they managed the enforcement of lockdown policy, realised it would be more cost-efficient to outsource the policing of their own rules to the banks and payment companies directly. But this is a strategically coercive dynamic. If payment companies don’t fall in line, they risk having their licences removed and their businesses shut down. Non-compliance is therefore not an option. PayPal isn’t perfect, but the pressure it is facing is very similar to the pressure pubs, restaurants and supermarkets faced under Covid. The structural problem here, as with the retail sector during Covid, is those payment companies are not legislative specialists. They take for granted that the governments know what they are doing and that the rules they are setting are human rights compatible and in line with the laws of the land. Nor do the payment companies have the capacity to investigate the rights and wrongs of every case. This is a job for the legal system, which is already excessively costly to access for most ordinary individuals.

This in itself is a huge blind spot for the financial system. There’s a very strong case to be made that the way democratic governments have gone about enforcing AML legislation is not compatible with human rights at all. The enshrined right of habeas corpus might even be under threat. The FATF has itself belatedly realised this. Back in October 2021, it noted in a “stock-take on the unintended consequences of the FATF standards” that (my emphasis):

Situations have arisen in the course of FATF evaluations concerning the interaction between the FATF Recommendations on combating TF (particularly R.5 and R.6) and due process and procedural rights (e.g. to legal representation, fair trial, and to challenge designations, etc.), which have been considered on a case-by-case approach as they arise in specific country contexts. In addition, the FATF has also been made aware of instances of the misapplication of the FATF Standards, which are allegedly introduced by jurisdictions to address AML/CFT deficiencies identified through the FATF’s mutual evaluation or ICRG process, potentially as an excuse measures with another motivation. This information often comes as a result of stakeholder input or when the attention of the FATF or its members is drawn to a particular issue, such as when another international body is reviewing legislation or actions are taken by national authorities. Analysis in the stocktake has therefore focused on the due process and procedural rights issues most often arising in evaluations or feedback.

The stock-take identified the following factors as key examples of where misapplication of FATF standards had affected due process and procedural rights:

- excessively broad or vague offences in legal counterterrorism financing frameworks, which can lead to wrongful application of preventative and disruptive measures including sanctions that are not proportionate;

- issues relevant to investigation and prosecution of TF and ML offences, such as the presumption of innocence and a person’s right to effective protection by the courts;

- and, incorrect implementation of UNSCRs and FATF Standards on due process and procedural issues for asset freezing, including rights to review, to challenge designations, and to basic expenses.

Readers can hopefully see the issue.

The entire regulatory system since 2008 has focused on ensuring that the 24-hour payment banking infrastructure we have become used to will never face the risk of going down again.

Put bluntly, the style of service disruption currently being experienced at PayPal is something major banking and payment institutions are not supposed to be able to get away with. At least not for long. So yes, it does feel like a big deal.

For the most part, the practice of shuttering access through website maintenance, downtime or error messages is more commonly seen at cryptocurrency platforms during extreme bitcoin selloffs. Closing access to people’s accounts or pretending to do website maintenance often gives operators the time to raise the liquidity they need by slowing redemptions. But it’s far from a transparent or honourable policy.

For PayPal to have triggered a run on itself because it was merely following government orders is not just unfortunate, it is careless. But it also speaks of a deeper problem at the heart of the anti-money laundering regulatory structure. The entire system we have created may no longer be fit for purpose. Consider, for example, that despite many billions of dollars spent on FATF compliance, a company like Wirecard, whose business model in retrospect looks to have been based on fraud as a service (FAAS), could so easily rise to the top of the German stock market. Nor has any of the regulation been successful at combatting the type of electronic financial fraud (mostly based on phishing attacks or social engineering) that impacts users every day.

We need to seriously ask if the benefits outweigh the collateral damage also being incurred.

But while PayPal might not be entirely responsible for its own actions on the KYC/AML front, its business model may be more vulnerable to this sort of fallout than most people appreciate. The culpability for that lies with PayPal exclusively.

A key revenue generator for the group has always been the interest revenue it absorbs from all the customer balances it holds. (You may not have realised it, but if you have any significant sums in a PayPal account, you won’t be collecting interest on them.) A large outflow of deposits could easily inhibit the company’s ability to raise this income and harm its overall revenue-generating capability. (You don’t have to hold balances at PayPal to use it.)

More critical for PayPal at this juncture will be its inability as a payments company to access the central bank lender-of-last-resort backstop. That means if the group is genuinely facing challenges meeting transfer and redemption requests, it will only be able to turn to wholesale liquidity markets to make up the difference. The degree to which customer balances are locked up in harder-to-liquidate securities or bonds will largely determine its success here. Frustratingly for PayPal, in the current illiquid bond market, there’s a good chance that selling these quickly and without a loss could be challenging. The alternative path for PayPal will be to use these securities as collateral for temporary loans. But the expense here is potentially open-ended if there are no obliging counterparts. That may (or may not) be why the company is currently restricting transfers.

Before rushing to conclusions, it’s important to stress the company still has recourse to liquidity from fully-funded (in fact over-collateralised) entities. We may not know the makeup of that liquidity, but solvency is unlikely to be an issue over the longer term. The biggest problem facing users today will be uncertainty over how quickly they can transfer funds out of the PayPal ecosystem.

What I can say is that in the modern digital age, bank runs will be different. We may even long for the days when tellers transparently shut up shop when the vaults ran dry. At least it was clear what was going on. These days, on the other hand, it will become ever harder to differentiate a bank run from a maintenance issue on a website. Such matters will be shrouded in plausible deniability and uncertainty. Suffice it to say, corporate communication departments will always err towards disinformation of their own sort, that any such outage is nothing out of the ordinary.

Even more concerning is that in the event of a run, customers will no longer be able to tell if those with better connections aren’t unfairly cutting ahead of them in the redemption queue. Virtual queues may seem technologically efficient, but there’s no transparency to them at all.

That’s why if you’re caught out by any of these policies you already don’t stand a chance of getting your account back unless you have existing connections to the management or a platform of your own. None of this is progressive or encouraging.

Izabella Kaminska is the Editor of the Blind Spot, a financial news media service focused on the news everyone else is missing.

PayPal was not contacted for this piece, which is based on the opinions of the author.

Stop Press: PayPal has now done a reverse ferret, claiming the new Acceptable Use Policy, containing the threat of the $2,500 fine, was issued in “error”. MailOnline has the story. As Kyle Becker pointed out on Twitter, PayPal is claiming its new policy to fine users $2,500 per infraction for “misinformation” is, in fact… misinformation.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.