In a recent piece for the Daily Sceptic Toby Young asks whether “the lockdown dam is about to break“. In other words, are we about to see a sudden collapse in the general consensus that lockdowns were the right thing to do in the circumstances?

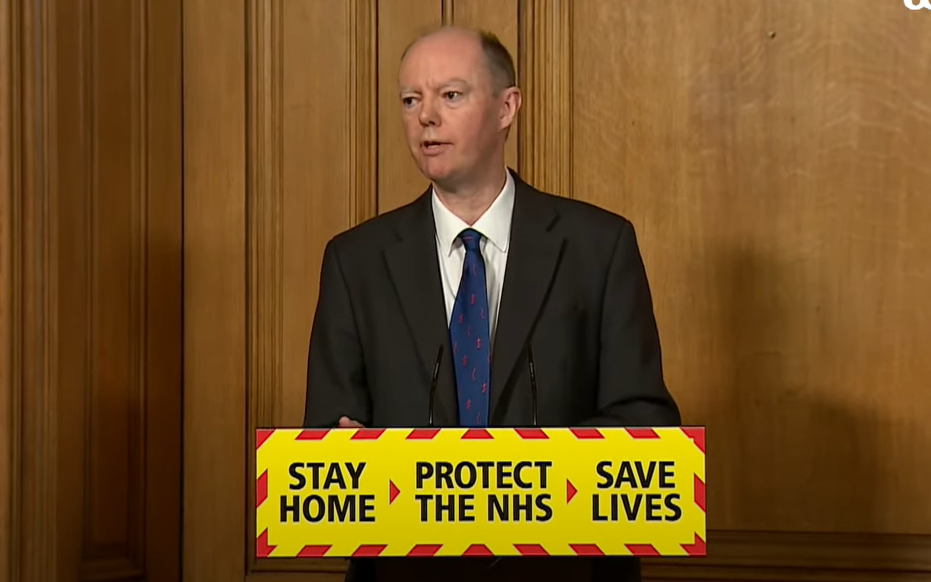

It certainly seems that a head of steam is building at the Telegraph and Spectator on the subject. But while I am sure that in 10 or 20 years it will be practically impossible to find anybody who fesses up to having supported lockdown, I’m not sure that the likes of Chris Whitty, Dominic Cummings, Matt Hancock or Neil O’Brien (the Tory MP who acted as Witchfinder General for the Government during 2020-21) will ever publicly admit that the decision to impose any of the various lockdowns or associated measures was wrong. Nor do I think it likely that we will ever have a proper public reckoning with what happened during the Covid period.

In Aesop’s famous fable, a fox, having desired some grapes but been unable to reach them on the vine despite its best efforts, suddenly discovers it did not want them after all. From this we derive the expression ‘sour grapes’, of course, but the fable is of much wider application than that. What Aesop was really describing was a particularly acute form of cognitive dissonance which affects all human beings (possibly foxes too) when confronted with their own failings.

Cognitive dissonance is a well-known psychological phenomenon describing the intense discomfort we experience when forced to hold two mutually contradictory ideas in our minds. The discomfort is indeed so severe that most people take extraordinary steps to avoid falling into such a situation, and will often force themselves to perform all kinds of mental gymnastics in order to achieve this. Hence, desiring a big slice of chocolate fudge cake, but knowing that chocolate fudge is bad for us and we should not eat it (two contradictory impulses), we suddenly fixate on foolish justifications (“well, I walked a lot today”, “I won’t eat anything sweet tomorrow”, “I’ve been under a lot of stress so I deserve a treat”, etc.) so as not to have to confront the truth: we are going to eat something that is plainly bad for us. The reality, stated simply and plainly, is just too stark, so we create little fantasies to soften it.

The worst form of cognitive dissonance is that which the fox experiences in Aesop’s fable. This is the situation in which one’s most cherished belief – that one is intelligent, rational, capable, and indeed rather special and wonderful – is plainly contradicted by failure. This is terrifying for us for the obvious reason that, if this cherished belief is forced up against the reality of failure, it may simply be irrevocably shattered. Such a disaster must be avoided, and the natural reaction that almost anybody has to their own failure is to immediately discover alternate realities in which they would have succeeded were it not for reasons X, Y and Z. “I would have succeeded in getting those grapes off the vine,” the fox reasons to itself, “but I just didn’t really want them.” The truth – it just wasn’t capable of succeeding by its own efforts and that was that – is not reconcilable with its self-image, and an internal ‘just-so story’ must therefore be invented to escape the consequences of truth and self-image colliding.

This form of cognitive dissonance faces almost the entire population of the country with respect to lockdown. For the actual decision-makers, such as Boris Johnson, Rishi Sunak, Dominic Cummings and Matt Hancock, admitting that lockdown was a mistake would be intolerable because it would mean also admitting to themselves that they made probably the biggest unforced error in peacetime history and are therefore not half as clever as they purport to be. For the hoi polloi, on the other hand, it would mean admitting to themselves that they were gullible and foolish, and in a moment of crisis simply decided to follow the herd – which, again, would hardly be a flattering self-portrait. Holding in one’s mind the notion that lockdown was a mistake is, in other words, irreconcilable with the notion that one went along with it and is an intelligent, thoughtful, rational actor. Nobody wants to experience the psychological consequences of trying to reconcile those notions, and they will therefore continue to avoid doing so.

Some people will achieve this through shifty evasions about how “none of us knew anything about the virus” at the time, “yes, but the backlog in the NHS would have been even worse if we had ‘let the virus rip’”, “we were just following the science”, “all the other countries in the world were doing it”, and so on. Readers of this site will be very familiar with this kind of baloney – we’ve heard a great deal of it.

Other people will avoid the dissonance through the classic smokescreen technique: getting angry. Dominic Cummings, for example, frequently exhibits this sort of posture – most recently in his response to Rishi Sunak’s comments about lockdown, in which he called the former Chancellor’s position “dangerous rubbish” and accused him of having a “melted brain”.

But the vast majority of people will, I suspect, avoid it through the most tried and tested measure of all – forgetfulness. Readers will already have noticed that a kind of collective amnesia has set in when it comes to lockdown, so much so that its consequences are barely mentioned even when they are plainly evident, as in the case of skyrocketing inflation. The entire affair now seems to register with most people, if at all, as a dimly-remembered dream – and, indeed, Covid itself now seems to have been ‘memory-holed’ from daily life; I’m not sure I can remember the last time I even heard it come up in conversation. This is partly a function of the lightning speed with which the news cycle now rotates, of course, but mostly it’s because people – subconsciously, of course – have absolutely no incentive to remember, and every incentive to forget.

Hence, I think it very unlikely that we will see any mea culpae from pretty much anybody when it comes to the decision to enter lockdown. What I think is far more likely is the scenario I briefly sketched out at the start of this article: fast-forward a decade or so and there will barely be a sinner in the land who will admit they supported lockdown, but this will be the product of an almost entirely unconscious process. Few indeed will wish to confront the ugly truth and all that it entails, and few will ever admit to themselves – let alone anyone else – that they made a mistake in 2020.

Dr. David McGrogan is Associate Professor of Law at Northumbria Law School.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

What sources were there in addition to ICL. We’re there a lot of others.

has anyone studied their history, methodology and financing.

The Bill Gates Foundation heavily funded Ferguson. No coincidence there. It seems to be a no go area where any authorities are concerned as to how, why, who these pseudo-scientists are funded. Probably because there is so much money swimming around for those willing to do and say what they are told. Ferguson has been doing it for years, certainly at least 30.

Why do they keep mentioning “pandemics”?

The word “failure” implies that the perpetrators were intending to improve public health, and believed in what they were doing. I’ve seen very little evidence of that. The most charitable explanation is of very early panic once they were told the virus came from a lab, followed by doubling down to cover up the leak and the needless panic. Then there are other explanations that have even less to do with “public health”.

Democide. No other explanation is remotely plausible.

Incidentally, since they mention the foot and mouth outbreak, it’s instructive to remember that, like COVID, that epidemic started from lab leak from a government animal research laboratory in Pirbright.

Tot it up, and there seem to be more disease outbreaks from the units set up to study them safely than there are from nature.

Global List of Lab leaks.

I think they’ve missed a quite recent one from some sort of lab in China I believe.

Whitty testified to the Inquiry that overestimates of numbers are “useful for planning purposes.” It sounds so sensible to budget for all contingencies, doesn’t it, until you look at the real damage it does.

An overestimate would be useful if it had an approximate probably attached to it e.g. the model said there is a 5% chance of 500,000 deaths without lockdown. That way governments could have contingency plans for a worst case scenario and look for indications e.g. rapidly increasing number of deaths that the worst case may be happening before putting the plans into action. The problem with the ICL models is either that they only gave one figure for expected deaths, or decisions were based on the worst case even if it was stated by the modelers that it had a very low probability of happening.

According to the report cited, the modellers had at least some caveats, which were ignored by governments in forming policy, and made into firm predictions for the benefit of the public.

That isn’t to say that Ferguson et al didn’t want it that way, as he’s never apologised for the foot and mouth disaster or anything else he got wrong… just collected the gongs.

The book can be downloaded free as a pdf from the linked website.

https://www.westonaprice.org/health-topics/hpai-virus/#gsc.tab=0

And this is how food industries are being decimated – more nonsense “viruses.”

“Prior to the Covid outbreak, “most countries did have a plan to deal with pandemics”, Hanke told the Epoch Times, “but after the Imperial College of London’s ‘numbers’ were published, those plans were, in a panic, thrown out the window.”

I do not believe this. The bottom line is that national governments acted on instructions received from the Davos Deviants. The DD’s knew exactly what disasters the Lockdowns would create and the results we have seen fitted their sick, warped plans.

Governments did not ‘panic,’ they did as they were told. To suggest panic is to continue to support, even push the cock-up theory and we know that is BS.

Someone should tell Toby Young.

There is certainly a common factor with all these overestimates and ensuing disasters- one bloke called Ferguson. How on earth is he still being believed. He is a mathematician and nothing else. Well maybe an astrologist. Most lunatics who interfere with government and lives to this extent are usually ‘dealt with’ . He is more suited to the national lottery show like mystic Meg.

Actually he’s a physicist. His crap, totally wrong forecasts from the past are precisely the reason why he was listened to by those morons in government

How can it be that Ferguson has never been brought to book for his fantastical modelling that fanned the flames of Covid hysteria and informed governmental policy?

Perhaps he was telling people what they wanted to hear. Between Ferguson, SAGE and the government, the WHO and who knows who else, I could never quite work out whose hand was up whose backside – just that most or all of them were lying about almost everything.

I recall one of the modellers from (possibly) Warwick saying that they were specifically asked to model only worst case scenarios, not anything more realistic. Might have been the second lockdown.

I also recall Vallance airily telling the select committee that models are only “scenarios not predictions” so I don’t believe he was ever in a panic and he was in charge.

China’s lockdowns, which affected only 7% of the citizenry, were highly localized and very comprehensive.

To say Chinese lockdowns ‘worked,’ however, is misleading. Dynamic Covid Zero (the WHO Pandemic Manual repackaged) did work, and retained the support of 82% of Chinese.

https://www.conservativewoman.co.uk/french-riots-an-ideal-excuse-for-another-lockdown/

We on here are not alone in suspecting the French riots will lead to martial law and lockdowns.

I loathe Ferguson but I have to say I’ve rarely eaten so well as when the mad git made his mad cow prediction. I was buying great cuts for next to nothing, it was like paradise! If only he had made a similar prediction on red wine and beer!

On a serious note, I genuinely think he should be prosecuted. He has a track record of turning up with insane predictions and he has never even been close to the Universe let alone the ball park.

His latest sojourn into his fantasies was funded by Bill Gates to the tune of £22 million. Is that not cause enough for Plod to stop dancing and get investigating what he was actually asked to deliver by Good Old Uncle Bill?

I firmly believe that any modelling should have to prove it can model a known similar event to within +/- 5%. The factors are all known, the outcome is known. If modelling is any use then it has to be able to predict, with reasonable accuracy, past events, current events and possible future events. It really should be the acid test before Government even begins to accept it.

In the case of Ferguson this should have been obvious. His track record is appalling. I remember all those pyres of sheep all around the country. All the cattle destroyed. All the Butchers Shops ruined. Ferguson got his money and walked free to wreak even more destruction.

I accept anyone can get things wrong but his modelling is known to not work and has been known not to work for 30 years. Why was he allowed anywhere near any form of power other than cleaning toilets? Who appointed him to destroy all those lives in all those cases of his predictions? Why is it not being asked “Who the hell appointed Ferguson?”.

The problem with that is that models are tuned (arbitrarily) to make them “predict” past events. That’s how the climate models work: always right about the past (including when the datasaet is modified), and always wrong about the future, because they were not modelling reality but adjusted to fit.

As John von Neumann said: “With four parameters I can fit an elephant. With five I can make him wiggle his trunk.”

Climate and epidemiological models have dozens of parameters, each infinitely variable to taste.

No climate model can accurately predict the past climate, they have over a dozen different models which can “predict” periods of the climate within the parameters laid down. Which is like saying I can hit the bullseye on the dartboard every time if you give me 20 goes at it.