“Science must overcome its racist legacy“, is the headline of an article in Nature that appeared last month, followed by a commitment from four guest editors of colour to “help decolonise research and forge a path towards restorative justice and reconciliation”, a reparations-tinged evocation of South Africa’s post-apartheid experience.

It is both embarrassing and disgraceful that Nature, the pre-eminent British scientific journal, should surrender to an explicitly anti-science ideology.

Science requires the separation of fact from passion – “A scientific man ought to have no wishes, no affections, a mere heart of stone,” wrote Charles Darwin. In science, establishing fact should precede emotion. First prove your claim, only then decide what to do about it; Nature should be responsible for the first part, values and the legal-political system for the second. This recent editorial skips the first step and goes straight to values: if a fact is upsetting, label it ‘racist’. This is one of a series of social-justice editorials in Nature.

This kind of editorialising is inappropriate in a scientific journal. The most recent one also makes a weak defence for its social-justice case. For example, because the rise of European slavery coincided with the rise of science, science is supposedly both tainted and complicit:

During that period, a scientific enterprise emerged that reinforced racist beliefs and cultures. Apartheid, colonisation, forced labour, imperialism and slavery have left an indelible mark on science.

Does the coincident rise of science and, say, slavery, mean that one caused the other or, as the authors claim, science is somehow tainted because it developed when society was going in a bad direction? To demonstrate at this distance that science, or at least scientific ideas, caused or were caused by slavery is essentially impossible. (If there is any plausible link, it is more likely in a positive direction: as the industrial revolution advanced, the need for slave labour was reduced.) Some might also point out that it is common in history for things we deplore, like conquest, to result in things we admire, such as the Roman Empire and the art of the renaissance. Either way, we need to know the whole picture before condemning just one part of it. All we can say is that old ideas, or some of them, were wrong, although even that is tough given that we no longer have access to the data – contemporary information about the human populations, white as well as black – on which ‘racist’ conclusions were based.

The article does say something about “core racist beliefs”, such as the idea that race is a determinant of human traits and capacities (such as the ability to build civilisations); and the idea that racial differences make white people superior.

It is undeniable that people differ in many traits. It is equally undeniable that human population groups, however defined, also differ. Race may or may not be a ‘determinant’ of human traits, but racial differences are certainly correlated with trait differences: there are IQ differences between self-identified Asians and whites, for example. What I mean is, among people who identify as ‘Asian’ (in the U.S.) and people who identify as ‘white’ (in the U.S.), there are differences in average IQ, with Asians on average scoring higher than whites on average – a well-documented fact. Yet the authors of this editorial apparently consider essentially any demonstrable behavioural difference between racial groups to be a “core racist belief”.

No fact can be ipso facto racist. To assert that an empirical finding of cognitive differences between races is itself racist is a violation of the fundamental scientific commitment to truth. As for ‘superior’ and ‘inferior’, these terms either refer to measurable quantities, in which case they are part of science, or to value judgements, in which case they are not. Men are on average taller than women is a scientific claim; men are inferior to women, is a moral one, outside of science. The authors constantly confuse moral and scientific (factual) issues. They also seem to believe that only some facts are acceptable and others should be suppressed for ideological reasons – a view which is totally incompatible with the scientific mission of Nature.

The authors evidently believe that any attempt to study human group differences is inherently racist. Darwin is condemned because he believed in a hierarchy of races. But of course the races that Darwin encountered are not those we encounter today. Given Darwin’s perspicacity as a naturalist, the non-existence of genetics at the time and his compulsive attention to detail, who is to say that he was wrong based on the evidence he encountered? The political scientist Charles Murray and DNA pioneer James Watson are condemned for suggesting that intelligence is partly determined by genes, which is very likely true (almost all traits are partly determined by genes).

“By 1950, the consensus among scientific leaders was that race is a social construct and not a biological phenomenon,” the authors write – never mind the fact that a “consensus” is not the same as the truth. In fact, it matters not at all how you define ‘race’. What matters is the fact of individual and group differences, no matter how you define ‘group’. Self-identified groups are rarely identical in terms of almost any average measure, from IQ to weight.

The editorial points to a dodgy intellectual future for Nature:

[Future articles] will seek to understand the systemic nature of racism in science – including the institutions of academia, government, the private sector and the culture of science – that can lead either to an illusion of colour blindness (beneath which unconscious bias occurs) or to deliberate practices that are defiantly in opposition to inclusion. The articles will use the tools of journalism…

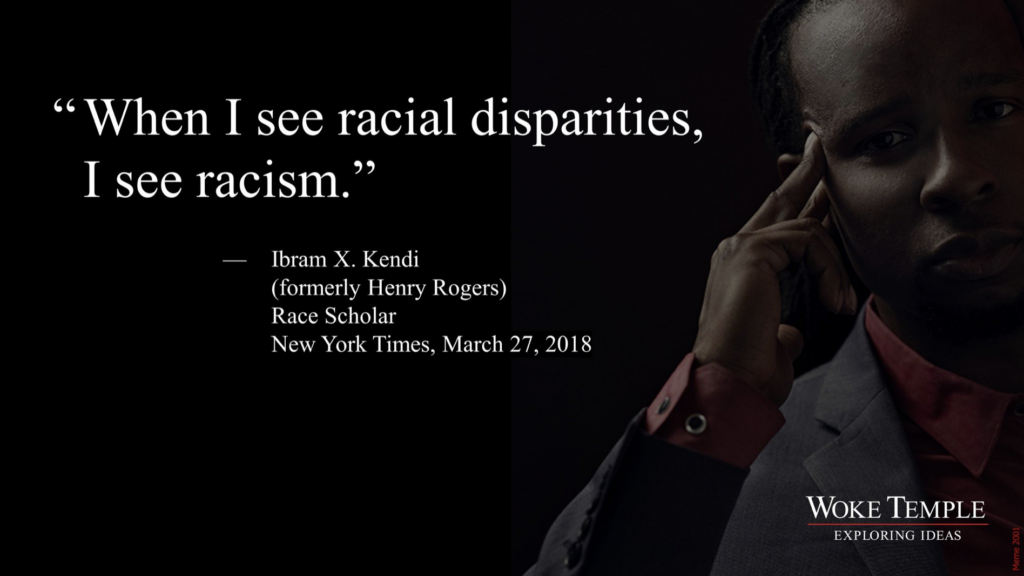

Systemic racism is just assumed by the authors. It is frequently cited as the pre-eminent cause of racial disparities in income and other social measures. But discriminating against people on the basis of their race is illegal in most Western countries and racial outcome disparities have many proximal causes – it’s multifactorial. You can only prove that systemic racism is a significant factor after you’ve eliminated all the other factors. The article ignores this issue and just takes if for granted that a major determinant of these disparities is “unconscious bias” – the existence of which is unproven and possibly unprovable. (The most popular unconscious bias test has been widely discredited.)

The editorial is also concerned about the eugenics movement, to which many Western elites belonged in the early 20th century, including most liberals. Fair enough, except that eugenics – state programmes designed to genetically ‘improve’ the human race – was a political movement not science and, in that respect, had much in common with the racial politics currently embraced by Nature. Science is a collection of facts; eugenics advocated interventions in people’s lives that most now consider immoral and probably racist. The fact that humans, just like other animals, can be selectively bred, doesn’t demand that selective breeding should be put into practice. Any action requires a motive. The eugenic proposals of Francis Galton and Arthur de Gobineau have no place in science. But Galton’s human reaction-time data and his analysis of fingerprints – and even his highlighting the obvious fact that the selective breeding of humans is possible – are just facts and should not be termed racist.

The article ends with a criticism of ‘European’ science:

[C]olonisation is sometimes defended on the grounds that it brought science to once-colonised countries. Such arguments have two highly problematic foundations: that Europe’s knowledge was (or is) superior to that of all others, and that non-European cultures contributed little or nothing to the scientific and scholarly record.

Again, the claim here not so much about science as values. Yes, in the 19th century most people in the West though that science (not ‘European’ science, but just ‘science’) was superior to the mostly unwritten knowledge of colonial peoples, not because ‘science’ was white or ‘European’, but because it was subject to being empirically tested – that’s what ‘science’ means. European scientists also made an effort to record and understand ‘indigenous scholarship’ (a fact the authors seem to deplore, even though some of the ‘scholarship’ they claim to revere would not have survived without this effort).

Many people still feel that in this culture war, science wins over ‘indigenous scholarship’; but the authors obviously disagree, even as they exploit Western “tools of journalism” to advance an ideological position that is the antithesis of the scientific ethic.

The reader can make up his or her own mind as to which view makes the most sense. But one thing is certain: introducing social-justice ideology into a scientific journal harms both science and justice.

John Staddon is James B. Duke Professor of Psychology, and Professor of Biology emeritus at Duke University. He is the author of, among other books, The New Behaviorism: Foundations of behavioral science, third edition (Psychology Press, 2021), Unlucky Strike: Private health and the science law and politics of smoking Second edition (2022 PsyCrit Press) and Science in an Age of Unreason (Regnery, 2022).

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.