I want to take you on a journey – a journey into data. What you take from this is up to you – perhaps you’ll gain a healthy scepticism of statistical data presented by experts; perhaps you’ll gain an understanding of types of tricks that might be used to massage data to favour a particular outcome; or perhaps you’ll even decide that government experts are far more likely to be right than a random person on the internet. All that I ask is that you come on the journey with me.

The journey starts with a statement made by outgoing Mayor of the city of New York, Bill de Blasio:

We want everyone, right now, as quickly as possible, to get those boosters. And we’re going to make it even better for you with a new incentive and an incentive that is here just in time for the holidays. As of today, we’re announcing a $100 incentive for everyone who goes out and gets a booster here in New York City, between now and the end of the year.

The former Mayor seems to think that there’s no doubt that the vaccines, and the booster vaccine in particular, offer the way out of the Covid epidemic. Let’s see what the data say.

Taking the Data at Face Value

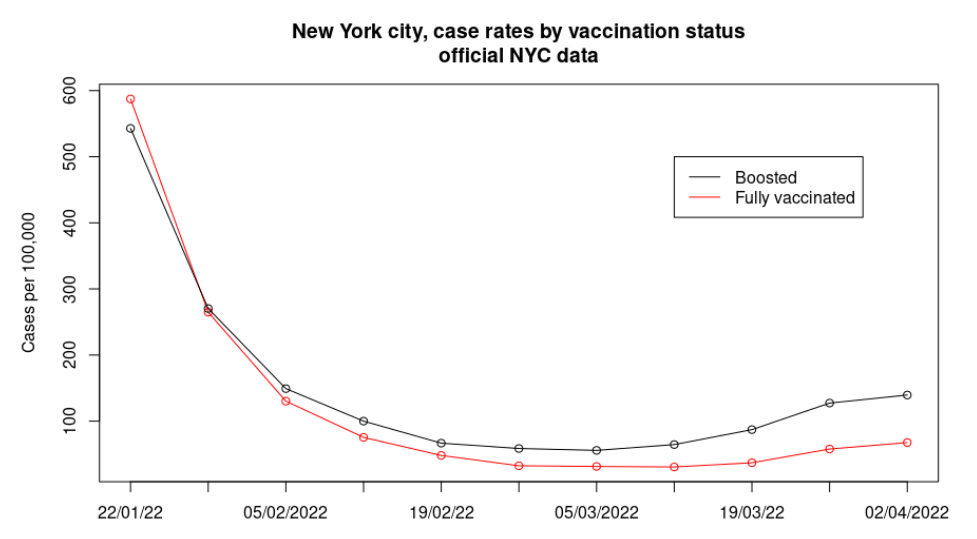

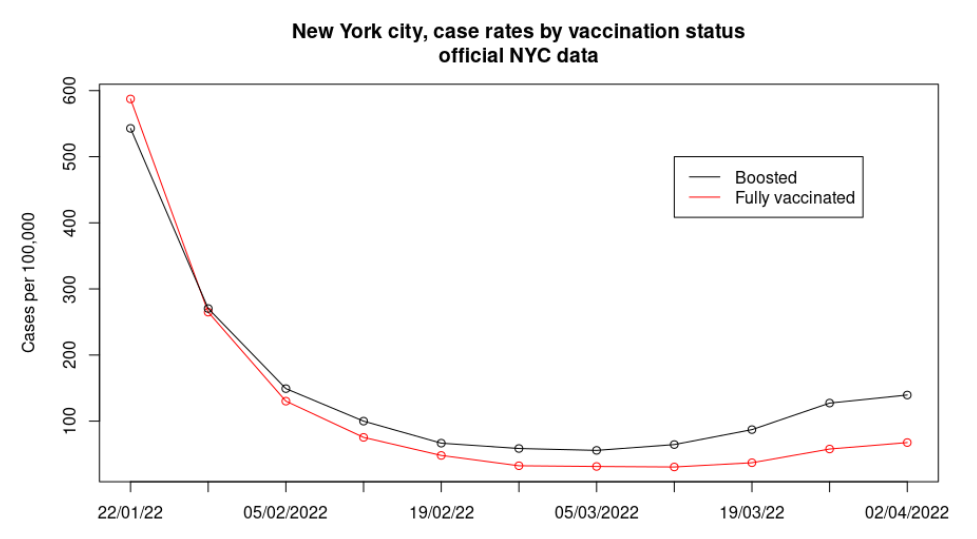

A quick exploration of data sources finds that New York city publishes a fairly decent collation of all of their Covid case data, and one document in particular contains data on cases and case rates by vaccination status – do the data on cases in the fully vaccinated versus the boosted support the Mayor’s faith in the booster?

That’s actually rather a surprise – even the NYC official data on case rates by vaccination status show that while the vaccine booster might have once offered some protection against infection with Covid, by late January the protection had been lost and in recent weeks case rates in those given the vaccine booster have been approximately double that of the fully vaccinated but not boosted. It isn’t clear why this is the case – perhaps it is the BA.2 variant of Omicron showing increased vaccine escape; perhaps it is the vaccine protection waning – all we know is that the boosted appear to be far more likely to get infected than the fully vaccinated.

These data suggest that de Blasio really should warn people that NYC official data suggest that in taking his $100 they’re going to be twice as likely to become infected, twice as likely to infect a vulnerable person and will be helping to make each Covid infectious wave far more serious.

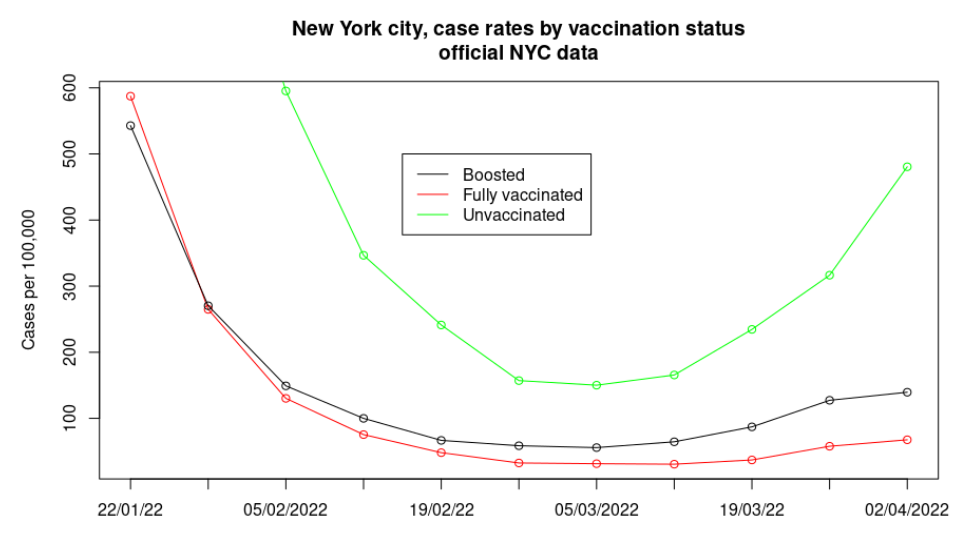

But of course, I’m being naughty here – I’m guilty of omitting relevant data. How do the unvaccinated fare?

Ouch. Perhaps the former Mayor should have focused only on the unvaccinated for his $100 bribe – these data suggest that the sweet-spot is to be fully vaccinated.

But wait – my spidey-senses are tingling…

The Date of the Data Updates

A quick look at the data for the unvaccinated versus the vaccinated in the graph above shows signs of a simple statistical pitfall. For most of the data points there’s a general agreement in the trend between unvaccinated, fully vaccinated and boosted – they generally all go up together and all go down together, even if there are differences of scale. However, the most recent data points (far right) buck the trend, with the data for the vaccinated showing only a slight rise (below the trend), but the unvaccinated a significant jump upwards (above the trend). This reminds me of a study I was involved in many years ago, where the early data that came in supported the goals of the study, but as the rest of the data came in we discovered that the rest of the data didn’t – our early data was biased. Has the New York infection data suffered a similar fate?

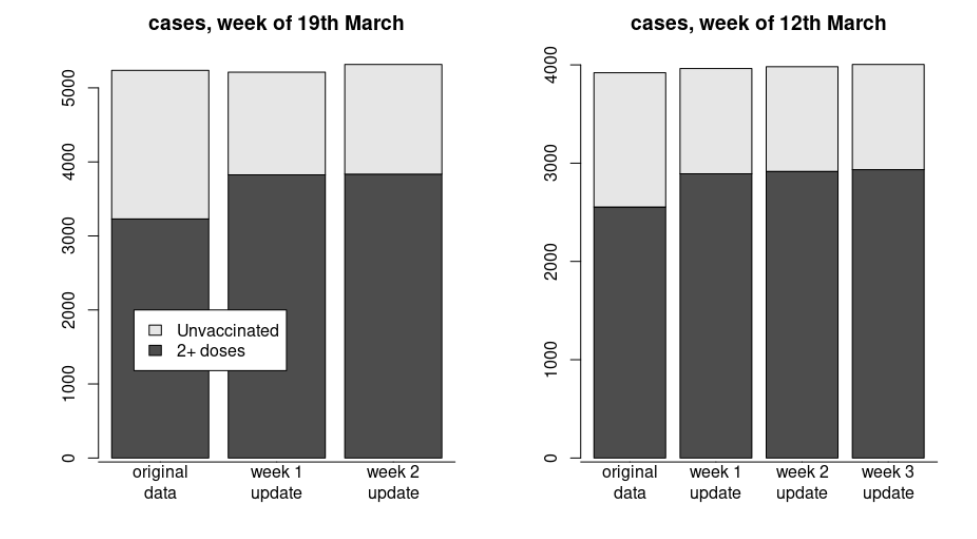

Fortunately, the NYC data is hosted on ‘Github’, a platform that not only hosts the data but also gives information on each and every update to the data – thus we can explore how data are updated after their initial addition to the database. To explore this aspect of the data we can’t use the most recent data (as there’s been no opportunity to update them yet), but we can look for evidence of the effect in prior weeks’ data – I’m going to pick two weeks as examples, data for the week of March 12th and March 19th:

Let’s start with the data for March 19th (on the left, above). When the data for this week were originally published it was stated that there were approximately 3,200 cases in those vaccinated with two or more doses and 2,000 cases in the unvaccinated. However, in the following week’s publication the data for the week of the 19th had been updated, to approximately 3,800 cases in those vaccinated with two or more doses and 1,400 cases in the unvaccinated. A glance at the update two weeks after the original publication shows that the figures had found their level – after that first week’s update there is little change in the data. The data for the week of March 12th (on the right, above) confirms the effect – exactly the same pattern is seen.

It is worth pointing out explicitly two aspects of their updating the data in this way:

- The NYC authorities are almost certainly only reporting the most recent data in their headline statistics and in their releases to the press. Thus they will be exaggerating the case rate in the unvaccinated and understating the case rates in the vaccinated. Sure, the update might be reported somewhere, but who wants to go trawling around in the data-mud when all the headline data are so easily found?

- There is only a week’s delay between the original publication of the data and the first update but this is where the bulk of the correction occurs. The data have already been delayed by two weeks before publication, so waiting an additional week to allow the data to settle down to their final state would seem the obvious choice. Are they deliberately publishing the data early to mislead the public?

But wait – I can see that the data shown above is hiding another problem in plain sight…

The Unstated Assumption

If you look at the bar charts of our two example data update periods you should see that in their updates they don’t actually add many new cases – the main impact of the update is to transfer cases from the unvaccinated into the vaccinated. This raises obvious questions, such as what on earth is going on?

When working with data there are all sorts of assumptions, most of which will be stated somewhere. For example, in the datasets we’ve been working with they define a case of Covid not as ‘all cases’ (as you might expect) but only as ‘cases in those aged over five’. The reasons for this definition of ‘case’ in the data are reasonable enough, but the important point is that they’re stated explicitly in the accompanying documentation. However, there are also unstated assumptions, and these are potentially dangerous. In scientific studies it is very important that all efforts are made to turn these into stated assumptions, so that readers (and team members) know exactly what assumptions are being made. This is often why scientific documents are very dry and boring – all of the ‘obvious’ assumptions really need to be tied down, to remove any source of error arising from different interpretations.

In the case of the NYC data and updates, the data quite clearly show that there are few additional new cases brought into the data set after the initial data release; rather, the update mainly moves cases from the unvaccinated group to the vaccinated groups. This is presumably a result of linking each case to the city’s vaccination database.

It very much looks as though there is an unstated assumption – that the vaccination status of all individuals is ‘unvaccinated’ unless proven otherwise.

Beyond this, it is also likely that there is a deeper issue. Even after the vaccination database links have all been found there will almost certainly be some cases apportioned to the unvaccinated group where the individual concerned was actually vaccinated (i.e., it simply wasn’t possible to link his or her status to the vaccination database). The magnitude of this effect is completely unknown (as they don’t offer the data), but in the U.K. the ‘uncertain status’ cases made up about 5% of all cases and I’m sure New York City would be similar.

It goes without saying that cases where an individual became infected within 14 days of becoming fully vaccinated will almost certainly also be counted as unvaccinated.

There’s yet another complication with this new assumption about what constitutes ‘unvaccinated’ – the NYC data includes both cases and the case rate per 100,000, so we can calculate the numbers that they think are in the unvaccinated, fully vaccinated and boosted groups. If we do this and add them all together we get a number that is consistently about 7,000,000. This is far short of the approximately 7,800,000 that the city authorities claim live in the city and are aged over five. However, the city’s own data on the percentage partially vaccinated suggest that these number approximately 700,000-750,000 – suspiciously close to our shortfall. This suggests to me that the team counting the cases simply don’t speak with the team computing the case rates…

All this talk of unclear vaccination status highlights another problem with these data – just what has happened to the partially vaccinated?

The Unstated Assumption II

The particular data set we’re working with only reports cases and case rates in the unvaccinated, the ‘fully vaccinated’ and the boosted, but not the partially vaccinated. This in itself is fine, even if it would be better to have been given all the data.

A quick note on definitions – ‘fully vaccinated’ in the U.K. is easy to define, as it is those having taken two doses of vaccine (possibly after seven or 14 days). In the U.S. this means those that have completed their vaccine course, which means two doses for some vaccines, but only one dose for others. Thus in the USA there is a group called ‘partially vaccinated’ which is made up of those that have received only one dose of a vaccine that requires two doses to be fully vaccinated.

However, the data remain troublesome. The first publication of the data appears to have some cases declared as ‘unvaccinated’ which are then moved into the fully vaccinated or boosted groups. But surely there will also be among the cases of ‘unknown status’ (but counted as unvaccinated) some who are partially vaccinated. The result of this is that we should see the cases that become identified as being in the partially vaccinated being removed from the data set, as the data set does not include a category for partially vaccinated. This means the first week’s update should see a reduction in total cases. Instead, we see that the data actually show a slight rise. What is going on here?

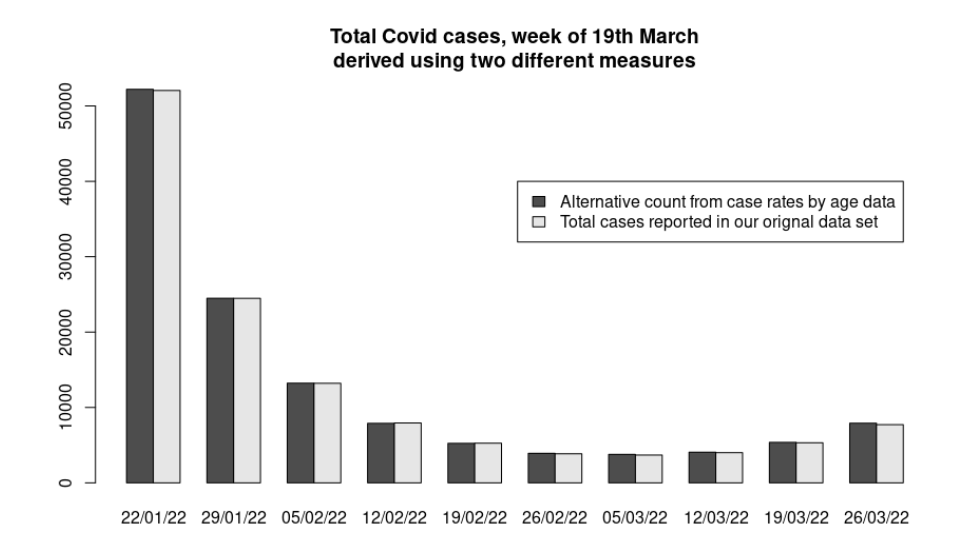

What we really need is another set of data giving total case numbers – that way we can remove the total given in our original data set (unvaccinated, fully vaccinated and boosted) to get data for those that are only partially vaccinated. This is made complicated by the fact that the data we’ve been working with are only for those aged over five years of age; most of the available data sets available to us are for the whole population. Fortunately, the NYC data page does offer case rates by age. As we know that the population they’re working with is approximately 8,337,000 and that approximately 6.3% of the population of New York City is under five, we can calculate the total number of cases in the over five population from those data and compare with our data set to obtain infection numbers in the partially vaccinated.

Well, that’s another huge surprise. Even though our data set purports not to include cases in the partially vaccinated, there’s just nowhere else for them to be – our estimates of total cases are very nearly equal to another data set that does include cases in the partially vaccinated. A quick check with the NYC data on total vaccinations given suggests that around 750,000 people are partially vaccinated – thus cases in this group should be large enough to be obvious in the graph above.

And so we return to the definition of ‘unvaccinated’ in our data set. It very much looks like a case in the ‘unvaccinated’ is actually defined as: Any case where we can’t prove that the person was either fully vaccinated or boosted. Or perhaps: Cases in those that are unvaccinated, partially vaccinated and where we just don’t know their vaccination status

The denominator

That last definition of ‘unvaccinated’ brings us to another problem – exactly how many people are going to be in this group? The New York health authorities will have a fairly good idea of how many people in the city have been vaccinated, and we know that they assume that there are around 8,337,000 people in the city when doing their rates calculations – but how many people are actually in the city. The latest U.S. census estimates that there were approximately 8,804,000 people living in the city in 2020 – really we need to use this number when calculating the unvaccinated population in New York city (it will probably be higher than this now, but the 2020 census estimate will be close enough).

In terms of our calculation of case rates for NYC by vaccination status, our original data set’s estimates of case rates in the fully vaccinated and boosted is probably accurate enough (apart from the most recent week’s data), but case rates in the unvaccinated should really be called the ‘not fully vaccinated or boosted’ and the denominator should be the total population aged five and over that aren’t fully vaccinated or boosted.

The result

We’ve gone a long way on this journey – we’ve seen evidence in NYC’s official Covid data that suggests that:

- The most recent week’s data are unreliable, significantly overstating cases in the unvaccinated and understating cases in the vaccinated.

- Just one week after the original data release they update the data – this moves a substantial number of cases from the unvaccinated group to the vaccinated group.

- Cases are probably defined as ‘unvaccinated’ unless proven to be in the fully vaccinated or boosted.

- That means ‘unvaccinated’ includes the partially vaccinated.

- And it almost certainly also includes cases that can’t be linked to the vaccination database, whether this be because forms weren’t filled in correctly, people vaccinated out of state or people vaccinated without paperwork (such as the homeless or undocumented migrants).

- And it almost certainly includes people within 14 days of becoming fully vaccinated.

- Finally, for Covid purposes the city assumes its population is about 8,300,000, even though everyone else, including the U.S. census, thinks that the population is about 500,000 higher.

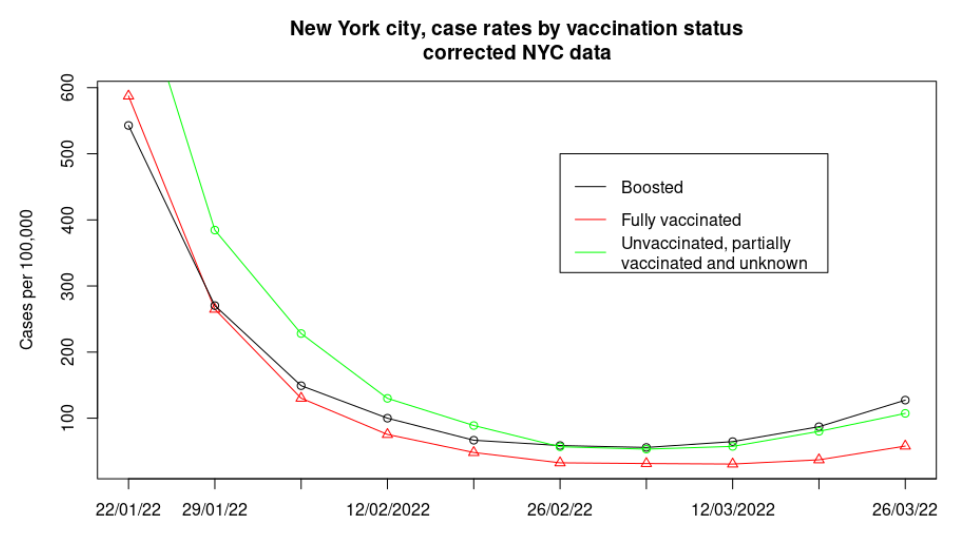

Let’s update our original graph of case rates by vaccination status with all the information we’ve gained along the way.

What a difference a little investigation makes – it isn’t that we’ve managed to add a small correction to their data, but that we’ve found evidence to support the actual rate in the ‘unvaccinated’ being substantially different to the official estimated case rate, even dipping below the case rate in the boosted in recent weeks. Note that we’ve not estimated the case rate in the unvaccinated, but in a strange group called ‘everyone not fully vaccinated or boosted’, which also includes every case where they couldn’t link the individual to their vaccination database – our estimate of case rates is almost certainly higher than would be found simply in the unvaccinated and partially vaccinated alone.

And so we can return to where we started our data-journey – Bill de Blasio’s generous offer to give $100 from the taxpayers of New York City to each person being boosted. You can take what you want from our travels, but perhaps you might agree with me that the data used by the city authorities to support their Covid strategy are nowhere near as robust as they believe, and that the $100 strategy is likely to make things worse.

I’ll finish with a question – how come any data analysis that shows the vaccines to be performing badly, making things worse or simply not necessary at all are ignored by the popular press, while no-one questions official data even when they’re full of holes?

Amanuensis is an ex-academic and senior Government scientist. He blogs at Bartram’s Folly.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

When I first saw this news I couldn’t believe it. I thought it was fake. It’s just too far out.

What it basically means is that our parliament no longer supports the presumption of innocence. Worst still, it is a willing participant in the lynching and attempted destruction of a person based on mere hearsay and unproven accusations.

I thought things were bad, but not this bad. This floors me and depresses me. I think that perhaps the feeblest of glimmers of hope within me that there might be something worthwhile left in our system has been pretty much extinguished. We are in dark, dark times.

Yes, it is depressing, especially as a lot of people will probably think it’s perfectly acceptable.

People have got so used to the government thinking for them, that they forgot they can exercise their own judgment. There will be plenty of people who find Brand’s behaviour abhorrent, even if he did not commit any criminal offence. They are perfectly within their rights to simply not watch his material, not go to his shows, etc. They do not need the government to decide this for them. If enough people dislike him, he would lose income without the assistance of the platforms or the government. If, on the other hand, enough people do like his material and wish to continue seeing it, and none of the material on any of the platforms is in itself criminal, the platforms should behave like Rumble and stay out of it.

Somebody pointed out the letter was sent by some committee, not the cabinet – irrelevant. It was sent on official letterhead and signed by an MP, precisely to imply that it was government-backed. The UK sense of fair play and respect for the law used to be held in high regard around the world – have no MPs any shame in bringing the country down to banana republic level?

Sorry to break it to you, but the UK has been a banana republic for quite some time now..

Put me in mind of Monsieur Gustave’s little soliloquy from ‘The Grand Budapest Hotel’ Stewart. “You see, there are still faint glimmers of civilisation left in this barbaric slaughterhouse that was once known as humanity. Indeed, that’s what we provide in our own modest, humble, insignificant…….Oh fu** it!”

If you haven’t seen the film, I commend it to you most highly.

Signal and Gab too. Telegram also seem to be standing strong, though haven’t read a specific statement yet. We need more Davids to stand up against these fecking Goliaths. Any news yet on Odysee, Bitchute, Gettr etc?

https://twitter.com/prestonjbyrne/status/1704599546829975641

Graham Philips British journalist, who has been branded a terrorist by the UK government, is still on Telegram.

People only realise what they’ve lost when it’s gone.

Chart your own path, seek no protection from any authority. Travel is best, it leaves you vulnerable to the kindness of total strangers.

Value individual interactions over everything.

Bit by bit we break the bastards.

“We are in dark, dark times.”

I’m lost for words.

Exactly Stewart. Simply unbelievable that a Parliamentary committee – not even Parliament itself but a small number of MPs- believe they can arbitrarily deprive someone of their living on the basis of unproven allegations. They clearly do not believe in the rule of the law they themselves are responsible for.

It takes a lot to say “we need a revolution” but the change in the balance of power unfolding since Covid mean some drastic change in governance is urgently needed.

Rumble is quite correct in its actions, and it made it clear that it didn’t expect the UK government to dictate what people can and cannot do by hearsay, convicted by a claque, the lawlessness of mob rule should be condemned not supported.

Judged and sentenced before the trial. This invokes images of the frenzied mobs hunting down heretics, witches or, in the Islamic world, anyone who shows disrespect to the prophet. It is positively medieval. We have fallen off the perch of justice, common sense, logic, reason, kindness, compassion etc and dropped into a completely different mindset. Now that the Online Safety Bill has passed, we are going to see more of this as ‘they’ round up, censor, de-platform, de-monetise all the truth tellers out there. They aim to silence us and once there are no voices speaking on our behalf, they’ll come for us, just like those well known lines that end…”Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.” Well, sod them, let them try.

With you Aethelred

Good for Rumble.

Personally, I’ve no respect for Brand but he must be considered innocent until proven guilty, the basis of British law.

I run a Bible teaching channel on YouTube, but due to my views on covidism (the vaccine harms), the 2020 Presidential Election (it was stolen), they removed a number of my videos.

I took the step to mirror the whole video catalogue on Rumble. Sure, it’s not as slick as YT, but it works and they don’t mess you around.

It’ll now be an interesting litmus test for the Online Harms Bill. Will HMG fine/block?

I have done a write-up on this here:

https://glitches.substack.com/p/who-is-caroline-dinenage

Good piece by this Prof of Law on the presumption of innocence;

”When people who do not have direct evidence concerning Brand’s alleged offences make arguments that assume his guilt, the rest of us know that, since they neither witnessed anything nor heard all the evidence tested in court, they cannot possibly know for “sure” one way or the other. As a result, they reveal themselves as people who share the qualities of a state that does not maintain the presumption of innocence in its legal procedures.

And this can have certain potency. As John Stuart Mill pointed out long ago, the law and its police, courts and prisons are not the only instrument of censorship. Similarly, they are not the only way to restrict the lives of citizens. Stoking outrage, hysteria and fear in civil society can do that too. Consider how YouTube has already decided to stop Brand making any money from his channel, though none of the accusations is proved.

Second, those who imply guilt without sufficient knowledge also reveal themselves to be people who are not capable of exercising real public authority, because their commitment to the public interest cannot be trusted. They are willing to defame another person on mere suspicion that the accused might have broken the law. True, they are not claiming to represent the public in the formal way a prosecutor does. Nevertheless, they discount the possibility that the accused may have done nothing contrary to the public interest in order to grind their personal or political axe.”

https://unherd.com/2023/09/russell-brand-and-the-presumption-of-innocence/

Vote Conservative, get communism.

Vote anything nowadays and get communism, fascism, corporatism……

Shouldn’t that read “Vote for any establishment party and get ………..”? There are centre right challenger parties, independents and indeed spoiling your ballot paper is a vote against the tyranny in our midst.

Vote Tory/Labour/LibDem/Green and get Corporatism and rule by unelected supranational bodies. Corporatism, according to a quote attributed to Benito Mussolini, is the more apt term for Fascism. Corporatism: “the merger of state and corporate power.”

This is the same Conservative party and Westminster establishment that not only doesn’t want to cancel ex-terrorist murderers but wants to have them in government in the UK. Whatever way Russell Brand treated women several years ago – which he long ago admitted, was remorseful and changed his ways – I’m pretty sure it was no worse than how ex-IRA terrorists treated women, and men, and children, and without wishing to minimise Russell Brand’s treatment of women, clearly nowhere near as bad.

If Russel Brand is to be cancelled, who else, and where does it end?

Well said.

Sincerely, hats-off to Rumble for standing up for morals, instead of politics like YouTube and all the rest of the sorry crowd of cowardly mainstream news and platforms.

Let’s hear it for Rumble!

Hooray!

Seconded.

Well look what we have here;

”I see Caroline Dineage MP has been going in heavy on social media companies who publish Russell Brand’s “conspiracy theories”, trying to tell the likes of rumble what they can and can’t publish online.

Meanwhile in other news her husband is a former Deputy Commander of the Army’s 77th Brigade, the unit which tackles legitimate criticism of the British government by British citizens online, err… sorry… I mean tackles misinformation and disinformation online by bad foreign actors.

I expect it’s all just another coincidence.”

https://twitter.com/A1an_M/status/1704776579421815017

I would like to see a statement from the Culture Media and Sport committee stating whether they stand by the letter. Dame Caroline’s letter seems to be under a CMS committee letterhead/banner and she signs herself as Chair of that committee. I want to know whether all members are complicit.

I find Mr Brand’s humour and behaviour on broadcast comedy quiz shows rather unpleasant and I’ve never actually paid attention to one of his performances. Just because I dislike the guy does not mean I think he’s a criminal. At this stage all we have are allegations: Is Mr Brand as pure as Sir Cliff Richard or as evil as Jimmy Savile, or somewhere in between? Given the very serious nature of the allegations I think it should be left to the police to investigate and that other media figures and politicians should butt out and let the cops do their work.

Current CMS committee members:

Dame Caroline Dinenage MP (Chair), Conservative, Gosport

Kevin Brennan MP, Labour, Cardiff West

Steve Brine MP, Conservative, Winchester

Clive Efford MP, Labour, Eltham

Julie Elliott MP, Labour, Sunderland Central

Rt Hon Damian Green MP, Conservative, Ashford

Dr Rupa Huq MP, Labour, Ealing Central and Acton

Simon Jupp MP, Conservative, East Devon

John Nicolson MP, Scottish National Party, Ochil and South Perthshire

Jane Stevenson MP, Conservative, Wolverhampton North East

Giles Watling MP, Conservative, Clacton

If any of these are your MP you might write and ask them whether Dame Caroline’s letter was sent on their behalf and then publish the response.

Anyone have an answer as to why Huw Edwards is still receiving his full £435.000 a year salary while he is ‘suspended during further BBC enquiries’?

Why didn’t they remove his livelihood immediately?

Where were the Government letters?

likewise Gates, Clinton and the other men who were using Jeffrey Epsteins special jet and island.

Difference is they are the establishment, and they protect each other.

Is he still suspended?? I just saw him the other day, but there’s something different about him that I can’t quite put my finger on…

https://twitter.com/CartlandDavid/status/1704059185460064353

Hahaha Fab……LOL!!

Seen it Mogs. Good though.

Why hasn’t the pervert Huw Edwards been sacked?

Three cheers for Rumble. Someone needs to inform Dame Caroline its innocent until proven guilty. What if a couple of people were to accuse Dame Caroline of being Racist, or

Anti Gay, they wouldn’t need to go to the Police, just post a story on social media. Dame Caroline could deny it all she likes but in her world to be treated as she expects Russell Brand to be treated would be that she lose her position in Parliament, be removed from any social media platform, be hounded by the Press, have her entire history paraded in the media and her life and that of her close families ruined. The accusers need do nothing else, they can fade away, as would the noise surrounding her post a few months, but mud sticks.

What a truly awful person, I wonder has she thought of a life in North Korea, it seems right up her street.

Incidentally the Google owned youtube can do one I am moving to Rumble, Googles owner spent a number of years being advised by one Jeffrey Epstein, it is no organisation to be telling others what is morally correct.

All pretence that pre-2020 government has been restored is gone – not that we believed it had been anyway. This is the same dictatorship that imprisoned us all. In behaving in such a crass, sinister manner, all the DCMS will do is confirm people’s belief that it’s a political takedown. (Has anyone ever considered how sinister it is to have a ‘Department for Culture’ anyway? It used to be the Heritage Department!)

The media coverage makes a fair criminal trial impossible, assuming Russell Brand is even charged with anything. The state’s involvement on top of the media’s has killed that. The press will doubtless now go after Rumble the way they did Parler.

I suspect there will be no criminal trial. Russell Brand would bankrupt himself going civil and suing, as libel and slander cases are very expensive and hard to prove. So he’ll be in limbo: publicly accused, but denied an opportunity to defend himself. Thus he’ll be treated as a guilty man.

So far, all old TV and radio shows featuring him have already been removed from archive TV channels and streaming services (his films might go next), his management team and agents have dumped him, his tours have been cancelled, his book publisher has ditched him, politicians who appeared with him in the past have rushed to ‘apologise’ for being seen in his company. YouTube has demonetised him and I suspect they’ll kick him off sooner or later. Other social media firms might do the same.

Effectively, once the furore dies down, they want Russell Brand erased from existence. There are two warnings coming out of this. One, to Russell Brand, is: ‘Take your money, stop broadcasting things that embarrass us and disappear.’ Two, to the rest of us, is: ‘If we can do this to a high profile celebrity like Russell Brand, think what we can do to all of you!’

“Has anyone ever considered how sinister it is to have a ‘Department for Culture’ anyway?”

I have. Sinister and wasteful. Culture, Media and Sport. The extent to which the state should be involved in any of those things is highly questionable. I would start with – not involved at all. I don’t where the ideal line is in terms of what it’s sensible to get the state involved in, but I am sure we’ve gone way over it. We need to start with very little and build up again, but find ways to limit the buildup. Look at the USA, specifically at the Federal Government. The USA did not exist, it was just a bunch of states, I suppose under the umbrella of GB. The original vision for the Federal government was very limited, limited to things that would sensibly be its province like protecting external borders and regulating interstate commerce. Now look at it – constantly wanting more money and power and trying to trample on the individual state.

Yes, there’s been talk of a new convocation of states happening. The Democrats and Republicans hate each other nowadays, but by putting severe new limits on the powers of the Federal Government, both groups could effectively run their states the way they want to and offset an ‘unacceptable’ President.

The Federal Government really should only operate internally as a referee in disputes between states and externally as a voice for the country on the world stage.

Curtailing the Federal Government’s reach would mean the Dems could cope with a hypothetical President Trump and the Republicans with a hypothetical President Newsom, if neither they nor their Federal organisations have much impact on ordinary citizens’ lives.

Realistically, the citizens of a state in the USA should only need to care about who is the state Governor and who is in the state government.

Indeed, I imagine that was the original vision and while it has been severely impaired it sort of survives. They have completely free movement between states so if you hate the one you are in you can move somewhere else that is politically more to your liking – of course this breaks down if you allow mass immigration. Probably they could have allowed states to control their own borders for everyone who arrived after a certain point (I would pick some point before the Mexicans etc started arriving en masse, whenever that was).

The problem the Democrats had was staying electable once their raison d’etre – improving the lot of of working people – had been damaged by prosperity. So they favoured expanding the Federal Government and mass immigration. Of course lots of Republicans have been complicit in the idiocy too, especially the ones that are big fans of the Military and all of the myriad agencies.

Just to put it out there: I’m willing to sell out my fellow citizens for a couple of Glastonbury tickets.

“You are guilty until proven guilty, Winston. Pour encourager les autres. Say it Winston, say it!”

Wardrobe by Chanel.

Coiffure by Rats’ Helmet.

Folks – it is time now to STOP voting. Sadly, voting for the mini-parties will achieve nothing. Leave the polling booths empty at the next election.

That might have no effect – after all, in local elections, turnouts are often less than 50%, with the majority not voting at all. Perhaps you could spoil the ballot papers, as some do!

I have to agree. Voting is pointless and too often fixed.

She is a disgrace and should resign. zits this kind of thing that proves everyone was right to have concerns about the Online Harms Bill. Do not give these cretins power over anything, we have separation of powers for a reason.

Dame Caroline Dinenage, “MP who pioneered the Online Safety Bill”

Dame Caroline’s husband is Baron Mark Lancaster, who was Deputy Commander of secret intelligence 77th Brigade from June 2018 – July 2020.

The 77th Brigade during the pandemic, spied on social media posts critical of Covid vaccines. Their tweets were reported & censored. The then Head of Editorial for @X was Gordon MacMillan & like MP @Tobias_Ellwood are both members of the 77th Brigade.”

https://t.me/robinmg/30437

What happened with innocent until proven guilty?

My sincere hope is that when this stupid stupid woman falls foul of “ not aligning with her banks ideals” and has her assets taken away she will remember this moment and regret.

The people of this country have far more to fear from censorship and cancel culture than from a man who may or may not be guilty of a crime unrelated to his legitimate broadcasting. Debanking and cutting off income are the thin end of a very nasty wedge.

You know what to do Gosport. Kick her out at the next election. She doesn’t believe in innocence before proven guilty.

if someone was suspended from work whilst awaiting the outcome of an investigation – garden leave – or whatever – they would generally be paid. Why should anyone be expected to “work for free” or be denied the opportunity to earn a living / feed their family pending the investigation of an accusation – (short of being remanded in custody) ?

“pre-emptive response”

Are they really that thick or is it just part of the despair-inducing strategy?