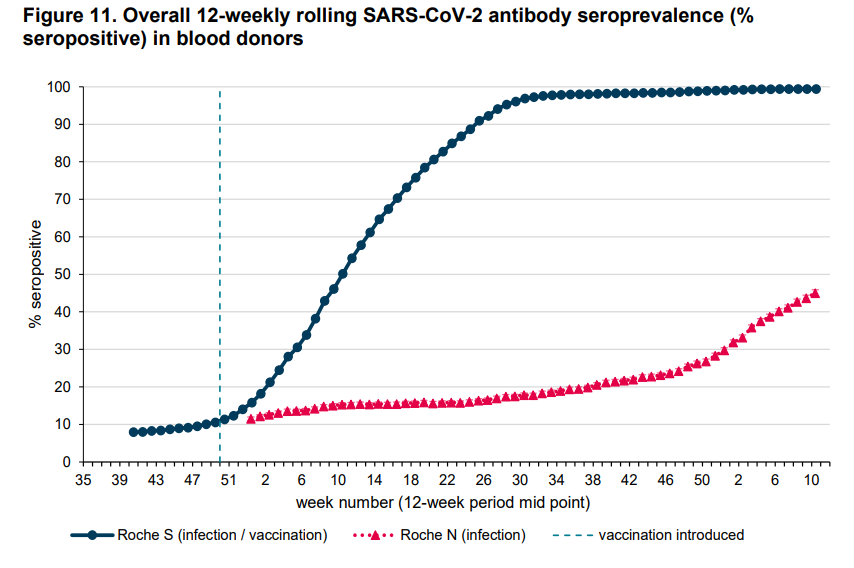

Among the more reliable guides to the real prevalence of COVID-19 are the data collected on antibodies acquired following infection (measured as N-antibody levels, in contrast to S-antibody levels, which are acquired from both infection and vaccination).

Below is the latest graph from the UKHSA showing how antibody levels in blood donors in England have changed since autumn 2020.

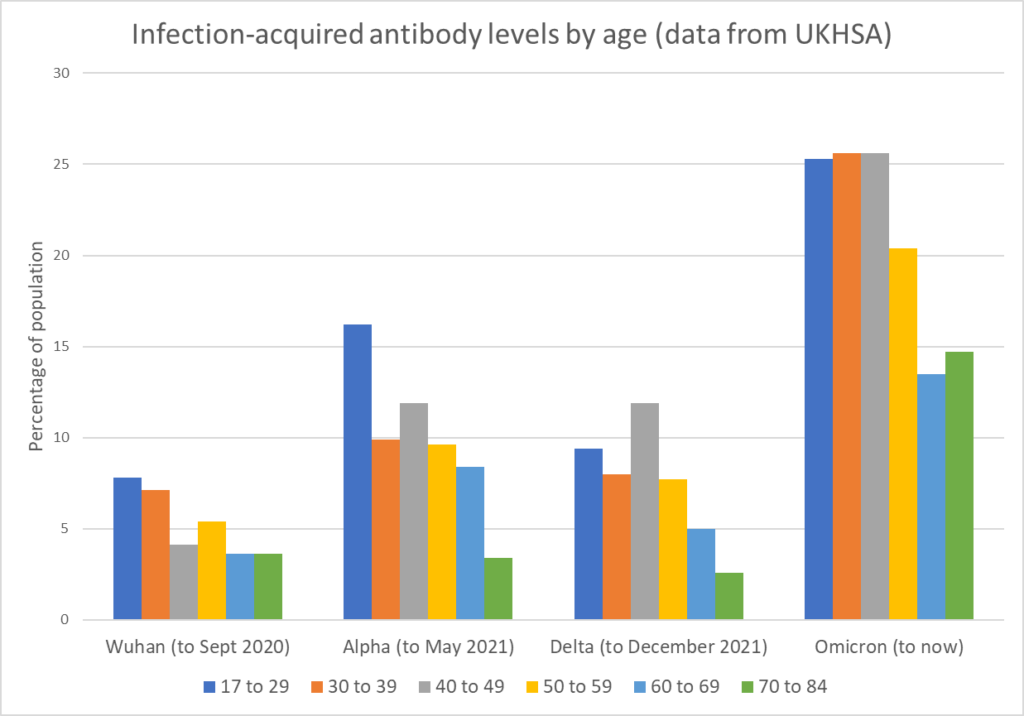

From this and earlier UKHSA/PHE reports we can infer that the first wave infected around 5.7% of the population (though data from this period is mixed, with some showing up to 8.3%), the Alpha wave infected around 9.9% (perhaps a bit less if you use a higher first wave estimate – either way the first two waves together infected around 16%), the Delta wave infected around 8% and the Omicron wave has infected around 21.4% (so far). On these data, around 45% of the country have now been infected at least once at some point during the four Covid waves. Note this doesn’t allow for any waning of infection-acquired antibodies, which would mean these are lower-bound estimates.

Dr. Clare Craig dug into the figures to see how this broke down by age, producing this chart.

What lies behind the differences in the sizes of these waves – is it differences in the variants and susceptibility to them, seasonal changes, the effectiveness of restrictions, the impact of vaccination, or something else?

Most likely it’s a combination. The winter waves (Alpha and Omicron) are both larger than the non-winter waves, for example, suggesting a role for seasonality.

It’s hard to read much into the role of restrictions on these data. For both the first wave and Alpha wave, lockdowns were imposed at a time when new infections appeared to be peaking – though how far that was a result of voluntary behaviour change is a matter of debate. Importantly, there was no Alpha exit wave as restrictions were eased (this was true in other jurisdictions as well), indicating that it was not restrictions that were preventing the spread. The Delta wave occurred at a time when restrictions were being lifted, yet it remained relatively small. The Omicron wave had only light measures (mask mandate, vaccine passports and work-from-home guidance) implemented in response. It’s hard to see much of a pattern here.

What about vaccination? The Delta wave is smaller than the Alpha wave, which may be thought to reflect vaccine protection. However, UKHSA data from the period show that reported infection rates during the wave were often higher in the vaccinated than the unvaccinated. In the large Omicron wave, too, reported infection rates have been far higher in the vaccinated than the unvaccinated. This suggests the large size of the Omicron wave may be due to vaccination making people more susceptible to the variant. However, the Delta wave, where the vaccinated also reported higher infection rates, was relatively small, so the intrinsic transmissibility of Omicron (or increased susceptibility of the population to it) may have played a part, alongside a seasonal effect.

I think the big story here is the large size of the Omicron wave (nearly three times the size of the Delta wave, and still going) despite coming at a time when most of the country had been vaccinated, 99% of the adult population had Roche S antibodies (from vaccination or infection) and 24% had Roche N antibodies (from infection). The variant’s partial evasion of natural immunity may have played a part; however, note that the large increase in antibody prevalence indicates it was infecting a considerable number of people (over a fifth of the population) who hadn’t caught Covid before – a greater number than in each of the earlier waves. The fact that the infection rates appear to have been much higher in the vaccinated raises questions about the role of the vaccines in driving this.

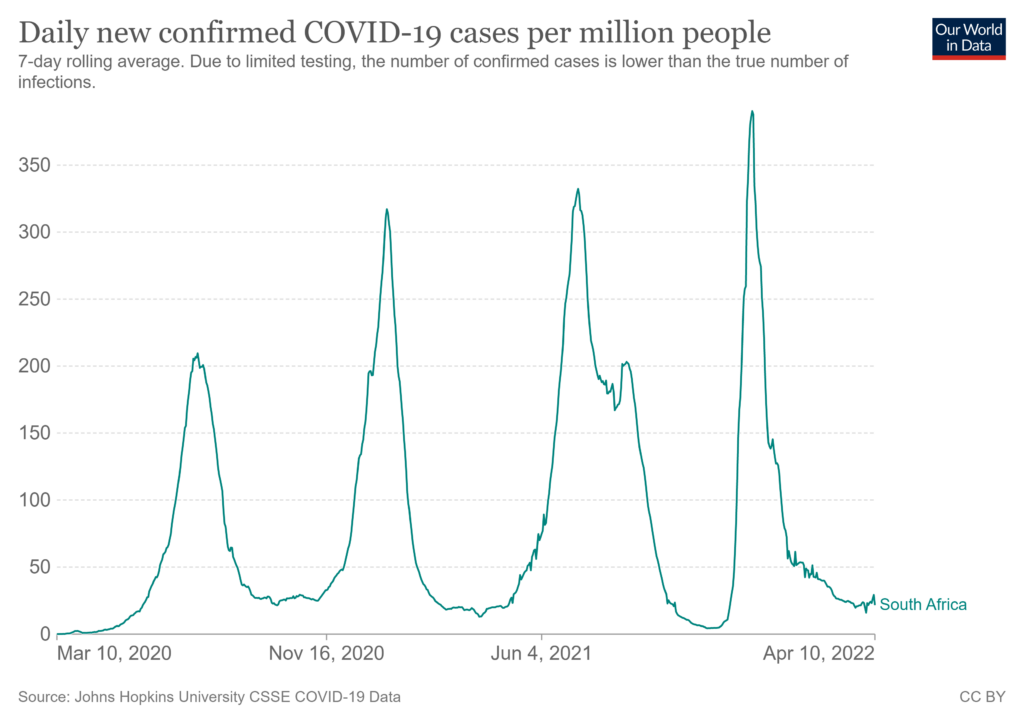

Consider that if (as some UKHSA data suggest) the vaccinated have twice the infection rate of the unvaccinated (or more), then if the vaccinated had the same infection rate as the unvaccinated the size of the wave would almost halve in size (as most people are vaccinated). That would make it a similar size to the earlier waves – much as it was in lightly-vaccinated South Africa.

South Africa has also not seen a new surge associated with the now-dominant BA.2 variant in the way the U.K. has in recent weeks. Does this give a clue to what is going on?

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Alternate title:

Do bears defecate in the woods?

“defecate” … So polite!

A1 presentation from phd and scholar Julianne Romanello aka Hearts Over Hexagons:

Inclusive Capitalism Buzzwords Part II

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c0wsVU30d94

Not if “experts” and “scientists” say they don’t!

Ah but are they talking about real bears or straw-filled bears like Winnie the Pooh?

To end the the scamdemic all you’d have to do is …

JUST.

STOP.

TESTING!!!!

Aaaand …… it would be gone.

i.e. two chances. One Fat. One Slim.

And slim just saddled up and rode outa town.

Exactly! Hub is going to see a band in a few days time, and the venue now wants him to do a LFT test, “for the sake of others!”

Ruddy cheek! Apart from everything else they have to be paid for now! Ain’t gonna happen…

Ruddy cheek! Apart from everything else they have to be paid for now! Ain’t gonna happen…

Are you in UK??

I give you GVB. Problem solved, just mandate jabs for everyone. Working out well so far is it not. OAS in action . I swear that I will shoot the next moron who utters the immortal words, “good job I got the vaccine, otherwise it would have been much worse.”

Explains it all.

Basically, if he’s correct, we’re all f****d – especially the jabbed.

A big thank you to the MSM,TRPTB and the sheep, for taking us down with you.

It will be an interesting summer when URI’s always wane – but wait….

Agree with most of you post. But, on a more positive note, doesn’t GvdB’s latest paper suggest that the unjabbed will escape the worst of it?

Here’s the ‘key message’ (page 5) from the recent (March) paper (my bold), link below:

I SERIOUSLY expect that a series of new highly virulent and highly infectious SARS-CoV-2 (SC-2) variants will now rapidly and independently emerge in highly vaccinated countries all over the world and that they will soon spread at high pace. I expect the current pattern of repetitive infections and relatively mild disease in vaccinees to soon aggravate and be replaced by severe disease and death. Unfortunately, there is no way vaccinees can rely on assistance from their innate immune system to protect against coronaviruses as their relevant innate IgM antibodies are increasingly being outcompeted by infection-enhancing vaccinal Abs, which are continuously recalled due to the circulation of highly infectious Omicron variants. In contrast, Omicron’s high infectiousness would enable the non- vaccinated to train their innate immune defense against SC-2 while the infectious and pathogenic capacity of the new SC-2 variants would be debilitated in the non-vaccinated for lack of infection- enhancing Abs in their blood. Unless we immediately implement large scale antiviral prophylaxis campaigns in highly vaccinated countries, there shall be no doubt that the pandemic will end by taking a huge toll on human lives.

https://uploads-ssl.webflow.com/616004c52e87ed08692f5692/6244c3b09ad5701f3ec17765_GVB_s%2Banalysis%2Bof%2BC-19%2Bevolutionary%2Bdynamics.pdf

Basically, it appears that the jabbed may be in deep shit.

My suggestion would be that there’s no surging ONS infection estimate for South Africa because there is none.

So this article points us in the direction of vaccination producing/engendering more and more cases? I think I have graph fatigue and the mention of anything produced by Roche doesn’t fill me with confidence. Could someone spell out for me in words of few syllables what this means/might mean going forward for both the jabbed and non jabbed in your opinion?

Incidentally, hearing anecdotally of more and more sudden cancer diagnoses in surprisingly young people. Lymphoma etc. Anyone else?

A never ending pandemic, with the vaccinated constantly sick and infected… with immune systems finding it increasingly harder to shake off new variants. And maybe susceptible to even bigger problems. And they would have gotten away with it if it wasn’t for you pesky (control group) kids.

Never mind the never-ending Covid, VAIDS means immune systems are unprepared for their constantly heralded enhanced Avian Flu ‘pandemic”.

Boosters keep the spike proteins working and the latest ‘officially’ gives only 8 weeks so called ‘protection’.

Who needs the graphs? Most of us had worked this one out shortly after their “Omicron” news was ‘released’.months ago.

Ryan Cole is looking at this:

Dr. Ryan Cole: COVID-19 Vaccines Causing An Alarming Uptick In Cancers (rumble.com)

Been with this site since it started. Rarely post.

Great data digging. Thanks. Fascinating stuff.

Observations – many people I know have just had Covid recently eg my Dr (who has taken everything he could to protect himself including a high grade surgical mask and outdoor consultations), my next door neighbour (with T1 diabetes so x4 jabbed) has just had Covid, my work colleague deemed very vulnerable by NHS (and x4 jabbed) so hasn’t left her house much in last 2 years and wears a thick black mask all the time has just had Covid.

I (unjabbed & never masked) – I’m 67 but fit and ‘normal weight’ spent 3 days at the Great Yorkshire Show last July and almost certainly got the Delta variant there – spent 36 hours in bed feeling rotten with a fever and then recovered on the sofa watching the Olympics for the following week. Unfortunately it finished off my taste and smell which still hasn’t returned. I’m resigned to it as unfortunate but will always refuse the jab unless and until I’ve examined the long term safety data. Which isn’t available and due to the unblinding of the trails won’t be.

What have we become?

Not “what have we become? “, more “what have they done to us?’

If you don’t take zinc supplements, then your loss of taste and smell could be a result of being very deficient. Your bout of CoViD, like any cold, will have nose dived your levels. Take Zinc and things may improve. If you take it long term, then take some copper too, as long term and/or high doses can deplete copper levels. Take vitamin d3 supplements too.

I would second this with my own experience. I don’t think I’ve had the coof and if I have had it then it didn’t affect my sense of smell or taste. However, I started taking zinc supplements a few months ago and I have noticed my sense of smell has recently become heightened. I’m beginning to think that I may have been deficient in zinc for some time.

I take all the supplements mentioned above but following a very mild dose of Covid last November still have very limited taste and smell. Anything else I could be doing??

Based on my own brush with omicron I’d say it’s partly that it’s so super-mild that “stay at home when you’re ill” would in more normal times be ridiculous. Not asymptomatic but rather fleeting and barely noticeable symptoms.

I had omicron as well and would describe it as the mildest cold I have ever had. Sense of smell went but is coming back. The vaccinated seem to be much more badly affected.

I’m 61, healthy, usually, and un-jabbed. Caught it 2 years ago and was pretty poorly for 3 days, but after that fine. I’m now on my second dose of it and going into my second week. Still crap – short of breath, cough but getting better. This has been worse and I don’t know why – especially if it’s Omicron. I’ve taken Ivermectin and all the vits but still nowhere near full fitness. Can only hope that my immune system is primed for at least another two years.

There is a nasty cold going around that seems to take weeks to clear the throat irritation completely. Much worse than Omicron. Are you sure it isn’t that?

Reckon I’ve got that now – miserable upper throat irritation. Haven’t tested so no idea if it’s the plague.

It is pretty shitty though, and by all accounts worse than O.

Apart from the occasional cold, the only thing I’ve caught in the last two years is enhanced immunity to bullshit.

But there are now “new variants” every week designed to overwhelm your immune system!

Note that infectiousness doesn’t map simply to case numbers — it is closer to an exponential function.

It is difficult to get a handle on the exact relationship, but simple modelling gets something like:

2x infectiousness -> 2.5 x more cases

3x infectiousness -> 4 x more cases

4x infectiousness -> 6 x more cases

The lack of a BA.2 surge in SA (and other African countries) is a huge red-flag.

Hi Amanuensis. In your previous article about New Zealand, the chart at the head of the piece came in for some criticism as it was labelled ‘per 100,00 population’, prompting the observation that the lower rate for un vaccinated infection was due to the high vax rate in the country. Was the chart labelled correctly, or was each curve representing the cohort of boosted, two doses etc.?

Are they using hcq, ivermectin or other anti virals/medication in SA like many other African countries i wonder.

Possibly, but the bigger story is we’re about to witness a tsunami of vaccine deaths and injuries, something the UK government won’t be able to cover up.

Once the noble medicos have identified this, the prosecutions can start.

Ye – n – y – n – ye – n – YES!

Dunno about omicron, but they certainly drive excess mortalities! :p

Petition to hold a public inquiry into the treatment of care home residents during the covvibollox, please sign:

https://petition.parliament.uk/petitions/614106

Done. Good one.

Done. Thanks.

Done. All four of us in this household. Thanks.

Who will they put in in charge? Hancock?

Done. Excellent.

Is it okay to sign if you’re not a UK citizen?

Official petitions are restricted to UK citizens or residents.

The longer this goes on, the more it looks like the mass vaxxing with the potions they rushed out will go down as the biggest folly and evil in medical history, by far.

You don’t need to stare at data too long to notice that the conclusive prove that the vaccines are safe and effective is simply not there.

It would be nice to agree with you and I REALLY wish I could but the brainwashing has been so effective that I doubt whether most people will ever ‘wake up’.

As Mark Twain said ‘it is easier to fool people that to persuade them that they have been fooled.’

Oh I meant for the already awake, not for the rest. I’m afraid we’ll be long gone before this is seen in its proper light – it will be historians, not journalists, that write it up truthfully.

I thought the plan was to abolish history along with ‘culture’ “childhood”and binary gender distinction?

History has long been a contested ground: genuine truth-searching and determined myth-making.

The myth-makers have better pr.

Not so sure of that. The times they are a-changing. The journalists who have been suppressed may have their day sooner than we think.

Historians will be writing of this for centuries. I’m being optimistic and deciding that we make it through all this crap – and with genuine historians!

I was thinking it might be an idea to buy several copies each of interesting books in proper hardback versions that fall apart more slowly.

I played a game with myself a few years ago, long before any of this – what books would i put in a safe for the future historians? I tried playing it with some friends who looked at me blankly and said “just put them all on a USB drive”. I felt a little deflated, as you can imagine.

I like my actual, physical books – beautiful things, designed to be held, put down and picked up again.

Definitely put in Senator R.F. Kennedy’s book ‘ The real dr fauci.

Also his new one about the childhood vaccination programme, this is to be published shortly I believe.

Re: Importance of antibody tests to determine community “prevalence” …

I wish there was better (more) data showing antibody “prevalence” in the public in the months BEFORE the official arrival of COVID. In America, CDC officials stated in a late May 2020 press conference that there was “no indication” the virus had been spreading anywhere in America before “latter January” 2020. However, as far as I am aware, there has been only one study of “archived” blood collected before this date.

The CDC did, belatedly, study 7,389 units of blood collected by the American Red Cross in nine states. The first tranche of archived blood was collected from blood donors Dec. 13-16, 2019. This study found that 39 of 1,912 of these blood donors (2 percent) tested positive for antibodies.

These donors were from the states of Washington, California and Oregon. Another tranche of archived blood collected in mid-January from six other states found another 80 or so positive specimens.

This “Red Cross blood study” was published November 30, 2020 – almost a year after the first tranche of blood had been collected. My question is why did it take almost a year to test (and later report the findings) of these first 1,900 units of blood? This testing could have been done in a couple of days.

As this DS article notes:” this doesn’t allow for any waning of infection-acquired antibodies, which would mean these are lower-bound estimates.”

This is a very important point as IgG and IgM antibodies do quickly wane (or are not detected by assays) in most infected people. Studies show that perhaps more than 80 percent of infected people will test “negative” for antibodies 2 or 3 months after infection.

My hypothesis is that the “first wave” of the virus might very well have occurred in the “flu season” months of November, December 2019 and January 2020. This is hard to definitively prove as there were no PCR tests in these months and the vast majority of people who were sick with COVID-like symptoms in these months did not receive an antibody test until April 2020 at the earliest. Antibody tests really didn’t become commonplace until May 2020.

This would mean that most people who possibly had COVID in, say, December 2019 would have been expected to test “negative” for an antibody test they received in May – 4 or 5 months after they were symptomatic.

That is, one cannot rule out “early spread” via antibody tests because enough people did not get these tests early enough to “prove” this might very well have been the case.

The one batch of stored blood from mid-December 2019 that WAS tested showed that 2 percent of donors had already developed antibodies by the time they donated blood. I’d also note that it takes about two weeks for IgG antibodies to form – which would mean most people who gave these blood samples were probably infected in November 2019 (if not earlier).

Given the importance of learning when the virus originated or began to “spread,” I still don’t understand why MORE stored samples of blood weren’t tested. Surely, there was stored blood collected before and after Dec. 13-16 2019 and from more than just three locations.

Questions:

My conclusion/hypothesis: It’s very possible the “first wave” of this virus happened when millions of Americans were sick with COVID symptoms in November, December 2019 and January and February 2020.

The virus was perhaps “seasonal” in 2019-2020 as well. That is, there might have been more people “sick” from Covid in January 2020 than there was in April 2020.

Maybe there is a reason that antibody tests were not administered to large swaths of the population until May 2020.

Link to Red Cross blood study:

https://academic.oup.com/cid/advance-article/doi/10.1093/cid/ciaa1785/6012472

Link to press conference where CDC said COVID was not in America until “latter January:”

https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/coronavirus-started-spreading-u-s-january-cdc-says-n1217766?cid=sm_npd_nn_tw_ma

I think I’m alone in questioning the veracity of the CDC statement from late May 2020 that none of their researchers had found any “indication” the novel coronavirus was spreading in America before late January 2020.

Above, I document 39 people from California, Washington and Oregon who had COVID antibodies when they donated blood Dec. 13-16 2019. I’ve also found 17 people mentioned in published media reports who said they were sick in November or December 2019 and later tested positive for antibodies (in late April or early May 2020).

These likely or possible “cases” were documented by reporters for The Seattle Times, Palm Beach Post, Fox News and NJ.com (the mayor of Belleville, NJ) and myself and a Birmingham, Alabama TV station (regarding a couple from Alabama). I also found one man who posted a message on the NY Times Comment section who said he was terribly sick in “the fall” of 2019 and later states that he got TWO positive antibody tests in the San Francisco area in April.

That’s 17 people plus the 39 Red Cross blood donors = 56 “indications” of “early spread” right there.

Of course, there were copious “indications” of “early spread.” I’d note that the CDC has never questioned any of the 17 individuals referenced in these published reports. I’ve read the CDC study multiple times, and also note that it seems no effort was made to question the 39 people whose blood did test positive. The blood samples were “de-personalized” or something like that.

Above I note. that antibodies do “fade” or wane fairly quickly in most people … but not ALL people. For example, antibodies were STILL present in detectable levels in the 17 people I uncovered from media reports and my own reporting. One lady I interviewed has now tested positive for antibodies at least THREE times. She was sick in late December 2019 and might still have antibodies in her system. Doesn’t it seem like ONE public health official or scientist would want to talk to her and test her blood with their own antibody assay?

Anyway, probably one of the biggest components of the COVID story – when it began to spread and where – is not really being investigated.

Anecdotally, I think there’s lots of reason to do the research you suggest. I know that in Nov 2019 the school I teach in had such a nasty ‘flu going round that the school gave out free hand gel and we were one teacher off having to close. One of my students actually lost his taste and smell for 2 weeks before the Christmas, and there were lots of kids hacking and snotting, and many more out of classes. I just had a cold myself, as I always seem to before Christmas.

In America, Influenza Like Illness (ILI) was “severe” and “widespread” in these months. It seems like everyone in my town was sick in December 2019 and January 2020. This was very common around the country and world. True, some of these people (about 30 percent maybe) had the flu … and tested positive for the flu when they went to the doctor. However, many who had all the COVID symptoms tested “negative” for the flu (I am one of these people and I was definitely sick with COVID symptoms in January 2020). If we didn’t have the flu, what made us sick? Why have I never tested positive for COVID since? (I think it’s because I have natural immunity – acquired from an illness I had when the virus wasn’t even supposed to be in my state or country).

There is still interest in finding out where it arose from. Having ruled out a ‘patient zero’ in Wuhan, the indicators are pointing to the source having been the world military games which were held there in 2019. The USA have refused to say whether anyone who attended, tested positive for covid. Other countries including Italy and China have been pushing for answers. There are quite a few articles on where this has got to on the internet.

The World Military Games scenario seems credible to me. It least it should be fully investigated. I would note that if this virus was present at those games it seems like there would have been many more cases BEFORE the “Wuhan outbreak” first reported on Dec. 31, 2019. But maybe the number of sick people were covered up or all these sick people were assumed to have had the flu?

One thing I’m SURE of: This virus was spreading around the world at least by October 2019.

Are blood donations from the ‘vaccinated’ tested for Covid spike protein presence?

I don’t know. Good question though.

I think a study of the millions of people who think they had COVID pre-February 2020 – those who tested negative for the flu and thus could rule that out – would show this cohort does have “natural immunity” to an extent greater than the population at large. This, I think, would provide more evidence that early spread happened.

Of course, I know such a study will never be done.

I don’t think so, at least not in the UK. The COVID FAQ on the NHSBT website just says that “It is very unlikely that the active ingredients of the vaccine will remain in the blood by the time of donation.” which I don’t think is true – there was that study that showed spike production continuing for at least 6 weeks after vaccination.

That’s a valid point, you would assume that the NHS app, and the various others that were pushed globally, being used to collect personal data on those who were “infected” would give them the perfect opportunity to screen those people for antibodies post “infection”.

Good scientific research, relies on robust data.

But that never happened, and as far as I’m aware was never even considered, simple answer is, they never wanted evidence of natural immunity because they can’t sell something that you can have for free.

The recent batch of Pfizer papers show that they knew from their own trials that natural immunity did not only exist but is more robust than the potion they are peddling.

This fact alone should have people questioning not only the jab, but the whole shitty scenario, then again after two years of programming by psychological warfare, I’m not really surprised that they don’t.

Interesting and pertinent post.

I don’t agree that the Omicron wave is an artefact of testing. Based on people I know and things like absences from work, loads of jabbed people have gone down with this and some of them have been seriously unwell for over a week.

Bit like the flu, then.

Yeah?

I’ve had that myself, too. But that doesn’t mean the Omicron wave is not an artefact of testing as its unknown how many of the people associated with positive test results ever got anything and as somewhat bad cold/ not-so-bad flu (three days of fever and being more or less off colour, bit of a sore throat, next week a couple of days blocked nose, ear swollen shut due to minor, ie, painless, ear inflammation for a few weeks) wouldn’t have been something which got a fancy name and which would have be hunted down with gene testing in 2019 (or earlier).

Dallas airport uses robots to scan for unmasked travellers

https://reclaimthenet.org/dallas-love-field-airport-is-using-robots-to-scan-for-unmasked-travelers/

Dystopian.

By Ken Macon

Stand by the road for freedom with our Yellow Boards next events

Tuesday 12th April 5.30pm to 6.30pm

Yellow Boards

Junction Broad Lane/

A3095 Bagshot Lane

Bracknell RG12 9NW

Thursday 14th April 3pm to 4pm

Yellow Boards

Junction A329 Reading Rd

& Station Approach

Wokingham RG41 1EH

Stand in the Park Sundays from 10am – make friends & keep sane

Wokingham Howard Palmer Gardens

(Cockpit Path car park free on Sunday)

Sturges Rd RG40 2HD

Bracknell

South Hill Park, Rear Lawn, RG12 7PA

Telegram http://t.me/astandintheparkbracknell

The only mystery here is why it has taken so long to work out something so blatantly obvious!

Over stimulation of the immune system inhibits it function to protect the host organism (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2654796/)

We know that the mRNA vaccine can enter any cell type and we also know that the modified spike protein produced is toxic and remains in the body much longer than the spike protein of a natural covid infection. Therefore the effect of these vaccinations is a partial silencing of the immune system to the spike antigen leading to an increase in infection.

I’m looking forward to seeing which funding body would pay for that research.

Urgent … last chance to comment on the WHO’s Pandemic Treaty (aka medical dictatorship and I assume Gates’s excuse to impose mandatory vaccination):

https://drtrozzi.org/2022/04/10/urgent-call-to-action-help-stop-the-whos-next-plandemic/

Already said to be too late to speak to the WHO meeting. Written comments are accepted before Wednesday 13th. though.

FFS, who do these globalists think they are, bossing people around like this and giving them absurd deadlines? The deadline to speak and give one’s verbal comments had passed by the time I read this.

I suppose one could complain to one’s MP … why leave the EU if the UK now signs up to an even more crooked organisation of unelected bureaucrats?

Thanks for the reminder, I’ve just submitted my thoughts.

It concludes with asking them to disband for the good of humanity.

But but but the planning notices have been up in Alpha centauri for 50 of your earth years, didn’t you notice?

The data may not exist but I am interested as to whether there is any difference here that distinguishes AZ from the Mrna vaccines. Any difference would implicate the Mrna delivery protocol.

Fascinating article thanks Will. All pieces of the jigsaw feeding into the picture, which isn’t looking too pretty right now.

Last year a report from the UK health security agency mentioned that those who’d been vaccinated seemed to show that vaccination had caused they immune systems to be “hobbled”.

From my own observations in the nhs most of my vaccinated colleagues have caught covid unlike unvaccinated me. Some may say I’ve been lucky but since September my family have suffered four bouts of colds and sore throats with my eldest catching covid in January. As for me nothing,throughout this time I’ve taken vitamin D which is the only thing I can think of why I’ve remained well.I believe the government are well aware that vaccination has failed and is failing to prevent infections. The question people should ask themselves is why did five out of six MPs vote to sack nhs workers? it’s not as if they didn’t have the information as a committee of MPs met scientists led by Professor sir Andrew Pollard who made it clear vaccination would NOT prevent infections.

Lastly why are we counting colds? Since December the virus as mutated to the point where it’s no more a pneumonia like illness but more like a bad cold.The evidence from hospitals is increasing rates of covid is not showing up as more admissions to ICU which probably explains why the government is ignoring calls for restrictions.

Hello due to me working in the nhs I got vaccinated at the end of January. The evening after vaccination I felt dizzy so cancelled my night out, normally I never get any reaction from vaccines so was surprised. Anyway on day five me and my family went to an indoor crazy golf place with lots of people. Felt as if I was developing flu or a cold but this feeling went away as soon as we left. Maybe this reaction was my immune system reacting to all the spike protein that would be floating around. Anyway I’ve decided not to get any more of the covid vaccines no one knows the long term effects they’ve failed to reduce infections. But then this was inevitable scientists told a committee of MPs the vaccines were NEVER designed to prevent infections only severity of symptoms. Since the start of covid I’ve taken vitamin D which as not only stopped me catching covid but all the colds and sore throats everyone else seems to be catching. Maybe scientists instead of looking at how to vaccinate everyone should look at why two thirds of the UK population have never had covid. To me that would be better than pushing a failed policy of vaccinating everyone.

Its very disheartening to read through all these comments essentially saying you all believe there is a novel condition called covid. Theyve won. We are so screwed. If this is the resistance, its a joke. You have all accepted their big lie about a new virus, even though you have seen conclusive proof that this whole agenda is based on lies and fraudulent “science” from top to bottom and transparently fraudulent metrics for recording deaths and that they have literally been killing people and calling it covid and assassinating heads of state who dont play ball. You know all of this yet still believe these liars and their fairytales about a novel virus out to get you and your nan. Tragic

The heroes promoting the covid scam unreality picked apart:

Addressing Dr. McCullough, Dr. Malone, and Dr. Cole’s SARS-CoV-2 Claims: Where’s The Evidence?

https://www.bitchute.com/video/STn5WseYjb6F/