Two years ago today, the U.K. climbed aboard the international lockdown bandwagon that had been gathering momentum in the preceding fortnight and ordered the whole population to stay at home. The aim was to try to ‘flatten the curve’ of coronavirus infections, and thus (it was said) ease peak pressure on the health service.

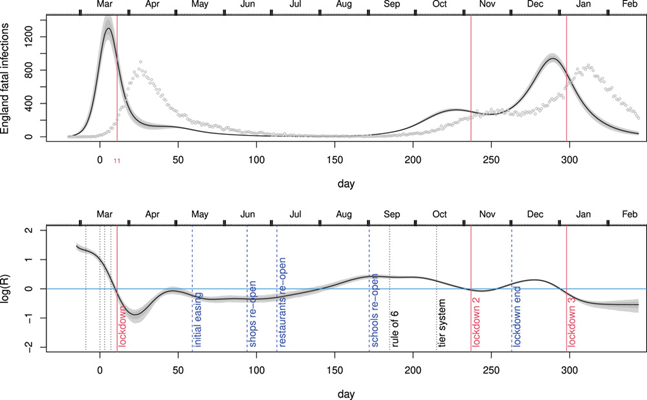

The policy, as it turned out, was completely unnecessary. As Professor Carl Heneghan pointed out as early as April 20th 2020, and Chris Whitty admitted to MPs that July, new daily infections were already falling ahead of the lockdown. The same thing happened on the next two occasions as well, as mathematician Professor Simon Wood has shown. All three times that the U.K. Government imposed a lockdown in England – March 2020, November 2020 and January 2021 – infections were falling before the restrictions came in.

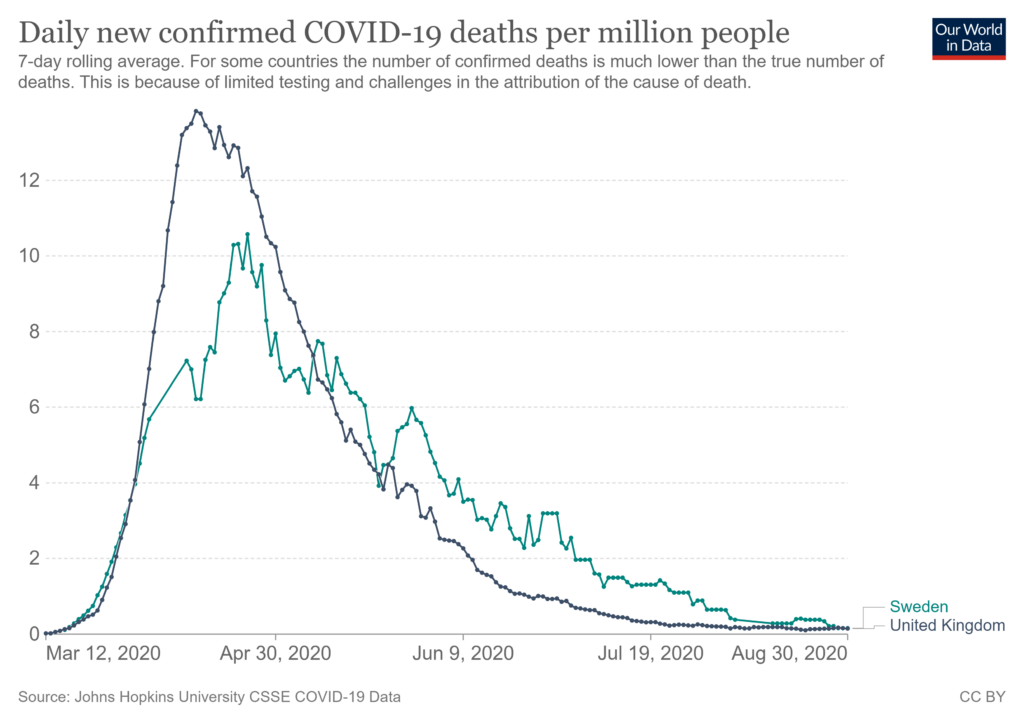

The fact that infections and deaths in no-lockdown Sweden – where people were never ordered to stay at home, and schools and businesses were never closed – also went into decline around the same time as in the U.K. adds to the evidence that lockdowns are unnecessary.

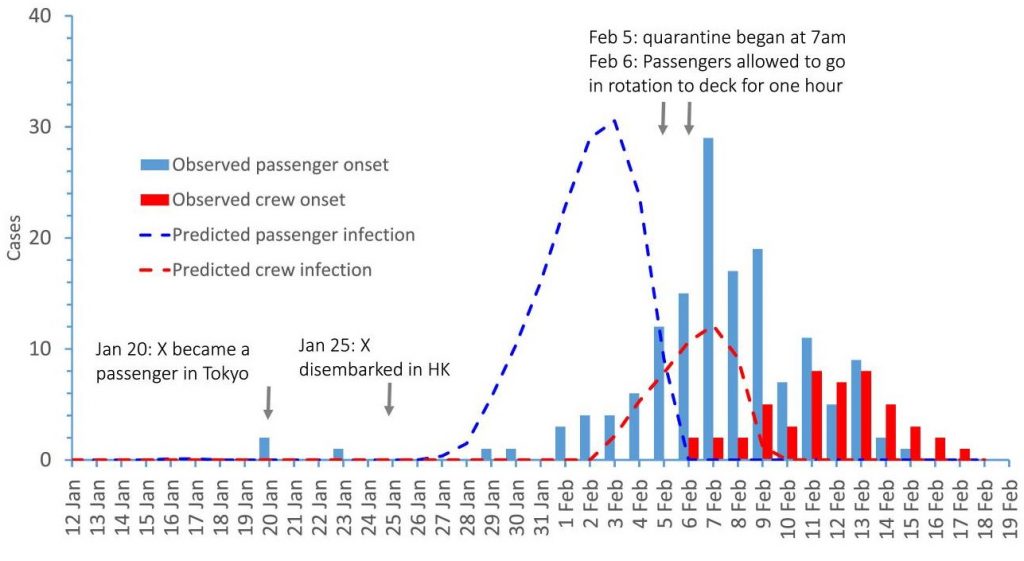

Further evidence comes from the Diamond Princess cruise ship, which, in February 2020, showed that a freely circulating virus in the confines of a cruise ship would peak and decline ahead of any intervention, eventually infecting a total of around 19% of those on board.

The evidence is clear: lockdowns are unnecessary to ‘control’ a coronavirus outbreak. Like flu outbreaks, coronavirus outbreaks peak and decline by themselves owing to factors such as pre-existing immunity and (possibly) voluntary behavioural changes in the population – though note there were no voluntary behavioural changes on the Diamond Princess, and nor are there typically exit waves as restrictions are lifted and people mix more, meaning the role of behaviour changes may be exaggerated. But either way, if infections decline ahead of lockdowns then lockdowns are unnecessary.

As well as being unnecessary, lockdowns are also ineffective. Where they are imposed before an outbreak is already declining they make little difference to the outcome. Many studies based on real-world data (as opposed to modelling) have shown this, and a recent paper from Johns Hopkins University (JHU) reviewing these studies concluded that “lockdowns have had little to no public health effects” and thus “are ill-founded and should be rejected as a pandemic policy instrument”.

The JHU study authors argue that prior voluntary behaviour change likely explains much of the ineffectiveness of imposing stay-at-home requirements on top of that. However, they also note that even with lockdowns and distancing in place, a considerable amount of contact continues, and some of the lowest mortality countries – Denmark, Finland, Norway – actually permitted the highest amount of contact in the first lockdown, allowing people to “go to work, use public transport, and meet privately at home”.

Even if lockdowns did have some effect, though, it would only be a matter of deferral, not prevention; everyone who was going to be infected would eventually be infected anyway. This might leave open the justification of flattening the curve, but since the NHS was never in danger of being overwhelmed, and given infections peaked and declined before lockdown, there was no need for such a costly ‘flattening’.

Lockdowns are not only unnecessary and ineffective, they are also devastatingly harmful.

Children were particularly badly affected, despite being at almost zero risk from the virus. Mental health problems in children increased 50%, rising from affecting one in nine before the pandemic to one in six during 2020 and 2021. Childhood obesity rates increased 20% or more above previous years. Around 100,000 ‘ghost children’ who were in school before the pandemic have never gone back.

Adult mental health has also been severely affected. The ONS estimates that the proportion of U.K. adults experiencing some form of depression is “more than double” what it was before the pandemic, increasing from 10% in 2019 to 21% in 2020.

Suicides in young women were up 25% and drug ‘poisonings’ in young men were up 12% in England in 2020. Alcohol deaths were up 20% across the U.K. in the same year.

The economic impact was considerable, affecting incomes and livelihoods. The U.K. economy shrank by almost 10% in 2020, the largest annual fall on record, while national debt jumped during the pandemic to £2.1 trillion.

The effect of lockdowns on poorer countries is terrible. The United Nations has estimated that an additional 207 million people could be pushed into extreme poverty over the next decade due to the long term impact of lockdowns.

Yet lockdowns were never part of the plan. The U.K. had a Pandemic Preparedness Strategy which, while primarily based on influenza, envisaged the possibility of a SARS-like pandemic and up to 315,000 additional deaths – well above the current U.K. total of around 133,000 excess deaths since March 2020. The strategy did not recommend lockdowns in any circumstances, implying they were ineffective and unethical.

During the pandemic the only opposition to Government policy has often come in the form of calls for restrictions to be imposed faster and harder. Now there is an official COVID-19 Inquiry and the worry is that the same will happen here, with the only criticism of the Government measures being that they weren’t severe enough or soon enough. Those running the inquiry and those presenting evidence need to ensure this doesn’t happen. The inquiry must be made to look at all the evidence, including the data which show that lockdowns were unnecessary, ineffective and harmful. Most of all, it needs to conclude that they must never happen again.

Postscript: It has been pointed out that this article does not mention that the Johns Hopkins paper was not peer-reviewed. The paper said that it examined 34 prior studies with data on the link between lockdowns and COVID-19 mortality, concluding that “lockdowns have had little to no effect on COVID-19 mortality”. However, several critics have noted that the meta-study defined lockdowns as having “at least one compulsory, non-pharmaceutical intervention”, meaning that even a mandate to wear face masks would be considered a “lockdown”.

Professor Neil Ferguson has been critical of this paper. He told the U.K. Science Media Centre: “This report on the effect of ‘lockdowns’ does not significantly advance our understanding of the relative effectiveness of the plethora of public health measures adopted by different countries to limit COVID-19 transmission.” In addition, Seth Flaxman, a University of Oxford computer science professor, has criticised the criteria used to determine which research was included in the paper’s analysis, telling the Science Media Centre that the paper “systematically excluded from consideration any study based on the science of disease transmission, meaning that the only studies looked at in the analysis are studies using the methods of economics. These do not include key facts about disease transmission…”

We are not persuaded by Neil Ferguson and Seth Flaxman’s scepticism about this paper. Its findings are in line with the conclusions of other researchers about the effect of lockdowns, such as this working paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research. It is not surprising that they are dismissive of attempts to assess the impact of lockdowns using real-world data rather than modelling data, given their own preference for modelling data. While it’s true that the Johns Hopkins paper has not been peer reviewed, it’s worth noting that Neil Ferguson’s highly influential Report 9, which used modelling data to make the case for lockdowns, was not peer reviewed either.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.