One of the most startling facts of the pandemic is that, between January of 2020 and June of 2021, Sweden had negative excess mortality – the country’s age-standardised mortality rate was below the five-year average.

Despite all the warnings about “disaster” and “folly”, Sweden actually saw fewer deaths than usual over this eighteen month period. (The ONS data on which this conclusion is based only go up to June of 2021. But it’s a good bet the picture hasn’t changed much since then.)

Even lockdown sceptics might find this difficult to believe. Sure, Sweden didn’t turn out to be the disaster that lockdown proponents claimed it would be. But can it really be true that there were fewer deaths than usual? What about those reports of Swedish hospitals “filling up with patients” in the winter of 2020?

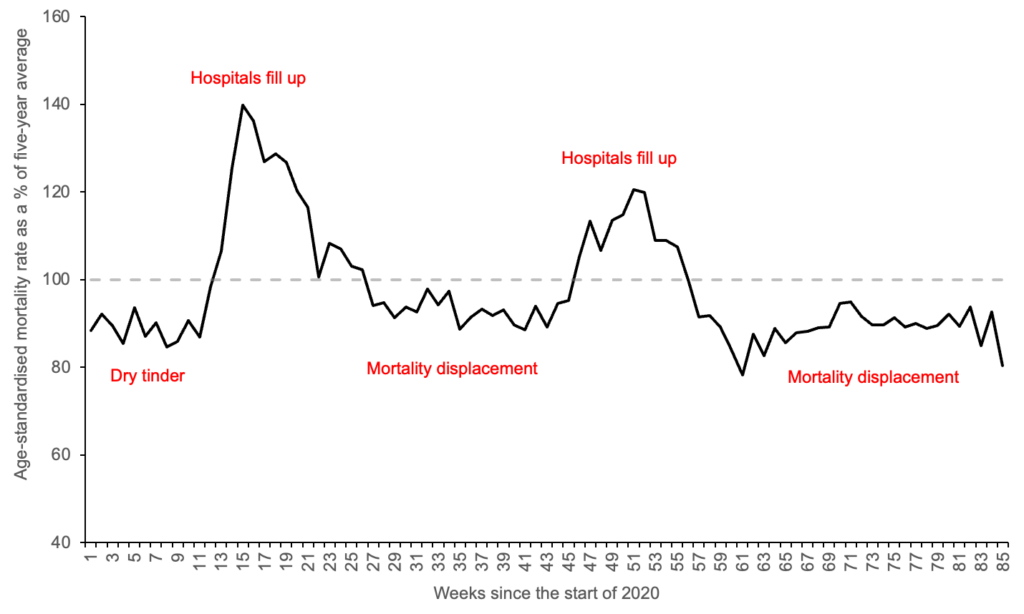

It can really be true. And those reports are easy to reconcile with the mortality data. You just have to remember two phenomena: the ‘dry tinder’ effect, and mortality displacement.

For those who’ve forgotten, here’s a brief reminder. The ‘dry tinder’ effect refers to the tendency for mortality to increase following a period of unusually low mortality, due to the presence of large numbers of very frail elderly people, who ended up living longer than expected.

Mortality displacement is just the opposite. It refers to the tendency for mortality to decrease following a period of unusually high mortality – for deaths to be ‘brought forward’ by some deadly event, such as a pandemic, heat wave or unusually cold winter.

Once you’re familiar with these two phenomena, you realise it’s perfectly possible for hospitals to fill up temporarily without the mortality rate going up at all in the medium term (over a period of several months or a year, say.)

The chart below shows the weekly age-standardised mortality rate in Sweden as a percentage of the five-year average, from January of 2020 to June of 2021. (I made the chart using data published by the ONS.)

In the winter of 2020, mortality was below average, leading to the build up of ‘dry tinder’. When the pandemic hit in March, mortality increased substantially. It then fell back below average during the summer of 2020, giving rise to mortality displacement. This pattern then repeated itself over the subsequent 12 months.

Aside from the obvious fact that Sweden’s approach didn’t lead to disaster (far from it), what’s the major lesson here? It’s that you won’t get a reliable picture of the pandemic if you only follow the news. After all, ‘Hospitals Fill Up With Patients’ grabs your attention, whereas ‘Another Week of Below-Average Admissions’ doesn’t pack the same punch.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Isn’t that discriminatory and against various laws including the ECHR which I understand we are still adhere to.

Personally I won’t panic as there will be another story in a couple of weeks time and I don’t go to large gatherings like football matches.

It’s not just about just what affects us. I visit two pubs on a fairly regular basis and these days hardly ever go elsewhere. However, I would be very unhappy if these pubs were the only two left.

We are being monumentally shafted by an utterly corrupt UK government, which is clearly in bed with the worst of the globalist depopulators. Resistance is vital.

They are in bed with Communists. We have a supine government ruled by a civil service that hates our democratic freedom and a bunch of advisers who belong to the Communist party. Johnson got done over by a leftwing nutnut who wants the world to herself, Gove slithered into the same house, the rest are not even of the Christian faith and hold our values. We have been rightly fckd

There isn’t much that is supine about the zeal they are showing for the destruction of our ancient rights and liberties, and our genocide.

It’s the only thing for which they have shown any consistent enthusiasm

Yeap – we have communism through the back door. It is now clear (as Peter Hitchens and other commentators such as Janet Daley have been saying) that communists have spent years infiltrating all the UK’s institutions. Covid has brought the results of this to light.

Nonsense.

LOL @ ‘UK government’. The ‘U’K government now has little authority over the ‘U’K and really only governs England. Given that you’d think there would be more English people in it.

Agreed. How to start the revolution? Who should head it? What can we do? Some practical solutions would be greatly appreciated from this neck of the woods.

We went to a massive anti lockdown demo in London ignored by the evil complicit Daily Telegraph. THIS IS THE EVIL THE MEDIA IS COMPLICIT

TRY THIS https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u0N_VzOVkXs

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GCI0NMgVfPk&t=1247s

Stand in South Hill Park Bracknell every Sunday from 10am meet fellow anti lockdown freedom lovers, keep yourself sane, make new friends and have a laugh.

Join our Stand in the Park – Bracknell – Telegram Group

http://t.me/astandintheparkbracknell

Home Schooling – Ex-Primary School Teacher on Resistance GB YouTube Channel:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kZ5oS2ejye0

https://www.hopesussex.co.uk/our-mission

Will who runs ResistanceGB was sitting down taking a breather from constant streaming and the police jumped him. He had to be lifted into the van after being checked over because one bloody copper gave him a beating. It was filmed and the same copper had given an elderly gentleman a beating earlier in the day.

I think people are getting to the end of their tether. They have obeyed all the laws and even the bullying diktats to keep everything calm. The government have taken this as weakness and run roughshod over the free thinkers. What happens now is anyone’s guess. Will is an extremely popular guy and we could all see how the crowd lost patience when Will was attacked. It only takes a few more protesters to realise that once the rules are broken, anarchy takes hold.

We have all seen how ANTIFA and BLM treat the cops and get away with it. We don’t want that violence on our side but I am concerned that something will crack if the Government doesn’t pull back.

‘The Police’ are, overwhelmingly, cowardly inadequates incapable of doing anything productive for society and with a grudge against those who are more capable than they. Training them to attack people who represent no threat to them is not difficult.

Is there a link to the film anywhere?

Wonderful, but is there anything like this elsewhere? I’m waiting for a similar thing down in thw wilds of Devon(Plymouth, to be precise). Anyone know anything?

The second video (GCI0NMgVfPk): “Video unavailable – This video is private.” Is there another copy anywhere else?

Agree. I’m no legal expert – but does not this constitute a hate crime, also?

Well I hate Zahawi, of course, it would be hard not too. Like the rest of our sold out government he is a sad lying apology for a human being. I was going to call him a lying piece of shit, but thought better of it, as shit doesn’t lie.

He’s not English (few in the ‘U’K government are) so cannot be expected to understand English values nor respect them.

No because the French have done the same and bared unvaccinated from certain parts of society. The country also adheres to ECHR More importantly they have issued a greater coverage of prohibited areas for the non Jabbers.

France is just the test bed here. If Macaroni can get away with it, then eugenicist Johnson will be all for doing the same here. If we see Paris and the rest of France burning, then fatso might think twice about doing it here, for a week or two and then he’ll be back with the same nonsense.

They do not care about niceties like laws and human rights. Communists never do. The sheeple of this country seem to be too scared to stand up to this.

Or too dumb to realise what’s coming

Discrimination is OK as long as one does not discriminate against those pigs who are more equal than others.

Trouble is there will be mission creep with this. Today it is nightclubs and football stadiums but before long it will be your local supermarket and cafe. Once introduced the population will then be under the control of and essentially the property of the state. It is then not too much of a leap to envisage a situation in a couple of years time where big pharma want to try an experimental vaccine on a population. All they will have to do is bung government ministers a few quid and the population will find they have to take this latest experimental ‘vaccine’ and have their passports updated in order to go about their daily lives.

Yes there can be no such thing as “fully vaccinated”, just “fully vaccinated for now”

And people said we were conspiracy theorists!

If the person you called a conspiracy theorist a year ago has been proven to be correct – then who exactly was the conspiracy theorist?

Still me, because I still have nothing more than theories about what is going on. Conspiracy Theorist is a label those who can think for themselves and see the wood despite the trees should wear with pride.

As seen elsewhere: shouldn’t conspiracy theory be renamed spoiler alert?

It’s a badge of honour

I think most people know deep down that a rubicon is being crossed.

The covid unvaccinated have been officially declared as undesirable and will be treated as second class citizens.

I will not tire of drawing the parallel with the Nazis because it is that serious and people need to wake up to it.

At what point did the Nazis’ plans for the elimination of Jews become a conspiracy? When Hitler wrote about it? When they were barred from many social settings? When they were rounded up? When maintaining the camps became too burdensome?

Two years ago no one would have believed we were capable as a society of forcing an unlicensed vaccine on people and discriminating against those who refused. But here we are.

The population rushing to get vaccinated and avoid discrimination will turn their backs on us unvaccinated just as millions of ordinary Germans turned a blind eye to the rounding up of Jews.

Just watch.

“It wasn’t the reaction of our enemies that shocked us, but that of our friends.” Hannah Arendt

The Origins of Totalitarianism is a brilliant work. Truly insightful.

Two years ago maybe not; one year ago, certainly. They did a survey at work a year or so ago and something like 50-60% supported compulsory vaccination for everybody (or all adults at least). Only something 15%-20% were completely against (I forget the middle options). Sample size would have been decent. I work for a global professional services firm and we all know what that means…

Give them another year and they will be calling for out physical separation from society if they are told by some authority that we pose a danger to others.

Walk around with that bell shouting unclean unclean.

If that happens, time to FIGHT BACK AND RESIST THAT AUTHORITY THROUGH ANY MEANS NECESSARY!!!

Who can doubt that camps are on the way?

Or those mega prisons being built

‘Democracy is nothing more than the dictatorship of the majority’ is yet another of those clichés that is a truism.

Wind up the majority, point them in the “right” direction and away they go

Yes.

The rub for the vaccinated is that the government cares not one jot for them. These naive people, having now drunk deeply from the poisoned well, have at least saved themselves the cost of a one way ticket to Switzerland.

Some small consolation is that those naive vaccinated people likely won’t be around for too much longer. That was always the Gates plan.

Points made in your excellent post: depressing, evil, demoralising, shocking…true.

This way for the showers. I won’t wear an exemption lanyard because I see it as a yellow star or pink triangle.

We are: there is clearly a conspiracy, several it seems, and lacking any definite knowledge of who is involved and what they are conspiring to do to us we can only theorise.

There is nothing wrong or embarrassing in being a conspiracy theorist, and the tinfoil hats are for those who think we are the mad ones; they need them, we don’t.

I am seeing it as a desperate last attempt to coerce under 30s into joining drug trial as numbers have been low in that age range. Vaccine passports should not survive a court case so will probably never come in but this would then be too late for those who were tricked by today’s announcement.

If they did survive a court case then we are all in serious trouble as that would be UK courts ignoring European Central Court and UK turning it’s back on 70 years of human rights laws.

Or to “convince” night clubs owners that they should implement such checks now as they’ll become mandatory, anyway.

The issue comes from the local councils who will then enforce this as a condition of license. Their powers have just been extended. This is all planned.

I hope to see every one of these cunts swinging from a rope one day.

Tomorrow preferably. You’ll find them at the Town Hall.

Unfortunately Human rights appear to have gone out of the window in my adopted country – as somebody who came to this country from the USSR I am very saddened by this

You might be better off going back there, and we might try and join you.

Even Putin has been leant on by ‘higher powers’. He does as he’s told now.

I think ‘Epstein lives and the Mossad or whoever ran him has all the pictures’ is a more and more credible explanation for what is going on.

The weird thing is that Boris and that other puppet are double jabbed and they caught the hobgoblin again…

So the Jabs aren’t even working at what they claim them to be doing amongst their own!

Assuming of course they’ve actually taken it and it’s not another exercise on psycho. manip.

They won’t have taken it, but pretending to have done so and then claiming to have Covid, which is highly likely a lie, is a ruse that could well backfire.

That is the part that is most frightening.

When Jews were branded a threat to German society, everyone knew it was nonsense but went along with it.

If the vaccines stopped infection it would at least be logical and semi defensible. The fact that they don’t and everyone can see they don’t makes.the whole thing so incredibly sinister.

‘The fact that they don’t and everyone can see they don’t … ‘

It seems clear that most people can see nothing of the sort.

The same in Ireal a lot of fully vancianted are getting cought out. It looks as if severe restrictions are to be announced.

Yes, can see that the jabs don’t really work and they know we can see it and we know that they know but they keep on full steam ahead. I wonder just how far they are capable of going before many more are awoken from their slumber.

Or maybe enough young have already taken the jab? If few had taken it up there would be protests at clubs being off limits. As it is enough are jabbed to fill clubs and exclude the few who will not have a big enough voice to be heard.

Personally my small protest is to remove all artists from my Spotify Playlist who appear in vaxxed only venues. Sadly, The Foo Fighters, who I’ve seen live many times were the first to go. Defund the Discriminators.

They won’t care. They don’t have to.

“We will always look at the evidence available and do all we can to ensure people can continue to do the things they love,” he added.

Er …. but by introducing vaccine ID cards you’re doing the exact opposite – you cunt!

Do you know, c*nt is my worst word. I don’t like it and don’t use it.

Or rather, I didn’t. But in recent weeks, I’ve quite accepted it. It’s the only way to describe the Johnson Junta. An absolute bunch of cunts.

Twunts is another word growing on me. I never used to swear but my latent Tourette’s came to the fore from March 2020. Now I can’t shake it off. Just the sight or sound of anything associated with governments, vaccines, passports, tests, lockdowns, masks, NHS and many other words triggers a torrent of abuse from deep inside me.

Better out than in, as they say.

I am just the same. My language is awful, and I shout and bellow at the TV (my other half will watch the news)….but all my shouting drowns out the telly, Haha!

More often I just leave the room.

Walking about and seeing all those passive aggressive signs telling you to wear a mask, keep your distance, only go one way etc, have me chuntering “fuck off!” as I go along.

Personally, I blame the government.

Me too. I also give the finger to the NHS ads at bus stops when out walking the dogs and can also be heard muttering “shut up” at the tannoy announcement in Sainsburys when its warbling on about keeping customers and staff safe.

My husband doesn’t understand why I’m so angry.

Ostrich. Head. Sand.

Add me to the list. I have a proud record of never swearing in public but the antics of our Antipodean clones of your lot, have me doing just sub-audible bad words about officious Covid marshalls, Covid propaganda signs, supermarket announcements about how they are keeping us ‘safe’ (my pet hate word now) whilst the radio and TV are sending me hoarse with much choice language. The Covid crazies have really activated my lizard brain!

Please remember that the phrase ‘take that damned thing off your face’ is NOT swearing. It is using the past participle of the verb ‘to damn’ as a simple descriptive adjective.

Lol…I mutter at those announcements too. Once or twice a little too loudly, which drew scornful looks from other shoppers.

Whenever bbc telly or radio 2 is on my favourite, almost automatic phrase is

oh, shut-up, you cunt.Why don’t you tear the signs down? I do wherever possible. Also tear up those vile signs on the pavements. They come up quite easily.

I know I shouldn’t and it is not my place to do so, but I curse Johnson and his evil and satanic government to hell at least 20 times daily.

Me too – I dislike using the word and in the past I would have only ever use it when I have been absolutely bloody seething about something – which is not very often at all – it takes a hell of a lot to wind me up – but these past few months I have been using it rather a lot recently to describe Johnson and that shower of c*nts he leads.

I usually have a love-hate relationship with most governments in power and I am willing to give and take on most government policies whether from Labour or Tory – but this Johnson government leaves me fuming – there is no two-ways about it – I absolutely loathe this government with every fibre in my body – I want it destroyed – I want that c*nt Johnson and the other c*nts who orchestrated this evil sham to suffer the same fate as the Nazi leaders did at the Nuremburg trials.

There can be no more compromises anymore – left or right, socialist or conservative – I don’t care what your political persuasions are this is much bigger than personal politics this is about our freedoms as a country – you either believe in our hard fought freedoms or you don’t – if you don’t then you are the common enemy of everyone who believes in freedom – you are effectively a c*nt.

Excellent post. Sums up my thoughts.

cent is not such a bad word. It’s another word for a penny.

It is a very crude word. There has to be a better one.

Cunt is a perfectly acceptable Middle English word and used at court, if Chaucer’s use of it is evidence. Shit (OE scit) is Old English; fuck Elizabethan and bollocks/bollox, or ballocks, late seventeenth century. All terms used by the great and the good of the day.

That is rude and a slur on part of the female anatomy.

It’s a term of endearment, you know you’re friends once the casual c*nting comes out – Mickey Flannigan

canting means talking hypocritically and sanctimoniously about something.

In the black country it just means idle gossip.

Oh dear. How sad. Never mind.

That’s cunt in Egyptian of course. Incidently, Chaucer spelt cunt cuente, and I wonder if the word is a diminutive of the Old English cwen for queen.

Freedom day:

Introduces mandatory ‘vaccine passports’ and backtracks on ruling out reversing restrictions.

I cannot believe once again they are backtracking.

Can’t you? I’m not in the slightest bit surprised, but the timing shows just to what extent they’re taking the piss. It also proves sceptics right yet again, though that’s just a conspiracy theory. . .

Not conspiracy theory, more spoiler alert.

It’s what they do. It’s what they always do.

Assume that whatever they promise to do, they’ll do the opposite.

Many of us predicted this sort of thing in the face of Covidiot denial.

“Medical condition that means they cannot be vaccinated”. Er, like you’re intelligent and realise the vaccine will harm your health?

Ah – will it be like the masks with some sort of optout to get round human rights laws?

Mother of the free? not if this happens.

… and has been untested for groups of which you are a member?

Yup, I check that box too

Does that include T-cells against the virus which contra-indicates the vaccine??

they have a cure for that – you’ll be forced to watch 24 hour reality tv while glued to twatface until you’re a dribbling moron. at which point you’ll think taking an experimental drug for a disease with a 99.9% survival rate is the “bestest idea evah”!

Do the LS editorial team still think this is a cock-up?

Great question!!

cock-ups do not come with censorship, bashing of free speech, implementing vaccine passports, killing people as proven remedies are not allowed (HCQ, ivermectin, sufficient vitamin D levels and other proven remedies.

Sick people that show signs of COVID or test positive for COVID with symptoms are sent home and told to come back for treatment once they are really sick. No we can’t give you anything that will make you better….. murder

Yup, murder it is, and on a scale magnitudes higher than Shipman.

We are looking at WWII slaughter figures.

I’m going to keep asking the same question over and over until people get it.

When does an idea become a conspiracy?

At what point did the Nazi’s ideas about getting rid of Jews become an actual plan?

When Hitler wrote Mein Kampf?

When the Hitler was elected chancellor in 1933?

When the first discriminatory laws came into place?

When they decided to round them up?

When they started eliminating them?

I watched the film “Another Round” today, the history teacher to his class:

Imagine an election, you have 3 candidates. No1 drinks, womanizes, has several serious health conditions. No2 smokes, drinks, suffers from depression, No 3 is respectful to women, is a vegetarian and likes art. Who do you vote for? Class says unanimously No 3.

Of course you will all know who they are: Roosevelt, Churchill, Hitler.

Van Tram justifying this (paraphrase): Night clubs are indoors and people drink alcohol there. (source: Guardian press conference blog)

I’m not aware of any “evidence” that Sars-CoV2 preferably infects people who “drink alcohol” and considering that all social-distancing requirements where lifted “alcohol and social-distancing don’t go together” shouldn’t apply anymore (insofar it ever did).

IOW, Van Tram has just removed any remaining benefit of doubt re: him being about “science” and not about some pre-conceived political agenda.

Was there ever such a doubt? I must have missed that.

It’s the first statement from him (I’m aware of) which openly uses “COVID” as justification for something political which cannot possibly have a relation to that.

So far, pushing the tee totaler agenda under the banner of COVID has mostly happened elsewhere, eg, Germany and South Africa.

Van Tram’s got history in this regard. https://mybodythispaperthisfire.substack.com/p/van-tams-bingo-slip

That would be the ‘Van Tam’ (with initials that could be mistaken for a really nasty set of infections) who has a nice juicy set of investments in Big Pharma – and who was warned against by Tom Jefferson when he was appointed through the ‘revolving door’ procedure?

Get ready for the resurrection of The Temperance Movement and Prohibition. Whoopy doo.

Let the youngsters have a restrained taste of freedom – then slap them down with the threat they will be denied entry in a few weeks, unless they are double injected with that shite in a syringe that doesn’t stop anyone from getting the ‘virus’ or passing it on. Yes, that one.

The subhumans orchestrating the panscam are getting more and more impatient to move on with their domineering plans. They truly are removing their masks now, further exposing their intent. This is when they will start making more and more mistakes in their eagerness…but it’s not over until the well built lady sings…Tick Tock.

You mean generously proportioned gender-neutral soprano. .

It’s “big boned” if you don’t mind!

As reported in The Telegraph (my emphasis):

The Prime Minister said they [the Establishment bottom feeding filth] may eventually mandate a certification scheme once everyone aged over 18 has been offered the chance to get vaccinated.

So WTF! Are they going to implement vaccine ID cards or not?

That’s Johnson’s statement from the actual press conference. The “vaccine minister” made the other announcement immediately before it.

I think we may mandate a change of administration once everyone has a chance to regret BBBoris.

And bring in who? That’s the most fucked up bit. The opposition want more

“opposition” selected by the same people

The obvious idea would be to theresa him — replace the guy who is really running the country according to the tune of a bunch of international “public health experts” as part of an informal coalition with the so-called opposition so that he can sideline the supposedly governing party(!) with some other guy from his party.

You still think there’s going to be an election in 3 years time ?

It’s not going to happen like that.

The opposition to this agenda is disparate and uncoordinated and widely dispersed across the spectrum of political allegiance.

There is no one focused opposition group with a charismatic leader able to draw together supporters and take the govt head on.

The talk of fight backs etc is OK , but fight what ? fight who ? , fight how?

The only hope is the underclasses rebel and take to the streets before it’s to late and then others can join and support.

The govt strategy is to slowly out flank and subdue each cohort of the population at a time either by coercion or bribery.

Most people , the vast majority will not make the first move against the criminal activities of the state and will continually step back and back, ceding ground . If their backs ever hit the wall they may fight back but by then it will be too late.

we are rapidly getting to the point of self preservation. They will control people by more fear and “cyber” hits to the internet. With no contact through forums like this , most rebels have no direct contact with any real

activist groups or any support groups.

Think about how to survive, keyboard fighting isn’t going to do it .

They are.

(if they can ‘get away with it’).

The answer is yes,

but they have to do it without being seen to do it.

The “injectable” remains experimental until 2023 at least and so can’t be mandated except by coercive measures and subterfuge.

and even while this is totally illegal, which court or parliamentary body is going to take up the case ?

I read yesterday that Pfizer is trying to get their concoction formally approved and licensed as early as January 2022 in USA! With it being ‘safe and effective’ of course.

Starting to go full authoritarian. Not surprised. The UK will join France, as well as, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan and Saudi Arabia – 3 countries that are dictatorships. Well done Mr. Zahawi!

Well – you’re either a Mengele follower or you’re not. There’s no in-between.

‘Which side are you on?’ is the key question. No mealy-mouthed double-speak allowed. Knicker-wetting fear or simple stupidity no excuse – you’re complicit with the fascists, with all that implies.

Just don’t let me see you going all pseudo-creepy-weepy, holding a poppy wreath as you disgrace the memory of previous generations.

Excellent post.

I can scarcely believe I’m thinking this, but I sense the rumblings of civil war. Think of the Catholics in Northern Ireland in the 1960s.

One way or another, the current impasse cannot endure. Either we and all we believe in goes under, or Johnson and his cohorts get their due. Anyway you look at it now, this ends in tragedy.

Indeed.

Blood will be spilled at some point.

Nadhim Zahawi , beautiful British name ( as Al Murray used to say , another twat since he was on a video promoting this shit) Anyway Zahawi !! What a sniveling shit weasel , my fist is fucking aching & not to pleasure him Clary style !! BASTARD !!!!

And no doubt yougov will be publishing a poll tomorrow showing 120% of all 18 to 25 year olds are totally in favouur.

Zahawi, Patel, Khan, Sunak, Javid – these are your gang masters now.

Admin wont allow my upvote.

And Kemal, don’t forget Kemal.

This is coercion plain and simple. Do they not realise the more you try to blackmail someone the more suspicious you appear? The 1930’s man with a mustache would be proud.

It’s nothing to do with “the evidence” and all to do with state control. It’s official, this is now a facist state.

Especially since double vaxed Javid is “infected”. And Johnson and Sunak are isolating because they might be.

So the utter absurdity of it would be comical if it weren’t so bloody sinister.

I seriously don’t know what to say. This is getting genuinely scary.

It’ll be cinemas and theatres next, then restaurants and bars.

Still no one cares.

When he says parliamentary scrutiny does that mean that an unholy alliance of labour lockdown loonies and Tory libertarians could stop it or is it just further executive tyranny with a pretence of democratic consultation?

Exactly. Starmer already whittering that we should still be locked in our homes and packing fucking health papers whenever we step outside.

Noticed as well that certain trades can ignore track and trace including train drivers. They’ll learn one day that the trains go nowhere without people like me. I control the signals. Absence of a driver means one train cancelled. Absence of the wrong signalller and the lot are cancelled. They never learn.

It’s getting clearer by the day that the govt has no faith in these vaccines at all. Zero. So what next? There is no fucking way out of this with these people in charge..

This is not a medical issue and never was.

C1984 was let loose in order to facilitate a prolonged campaign of fear, a vaccine was promised as salvation although the real purpose of the rNA injections was to kill and maim. Once the injections were out the next step was “passports” which will morph in no time at all in to full digital ID, which is what this has been about from the start.

Ultimately a depopulated rump of slave workers is all they want.

What a stuffing surprise. So the government chooses the path of discrimination. Will anyone oppose them (apart from possibly the Lib Dems)?

“Any places where large crowds gather”? How large? Sounds like they’re going for full on apartheid. Where’s our freedom? Bunch of crooks.

any protest sized gatherings.

Obergruppenfuhrer Patel made sure that is no longer allowed. And the 650 jellyfish rubber-stamped it.

Today large venues, tomorrow cinemas, restaurants, supermarkets, pubs, newsagents, .

Exaggeration?

Just three weeks to flatten the curve they said in March 2020 and now look where we are – battling for our very own survival as a free country against a government determined not to let us have our freedoms back.

They saw the backlash in France when Macron made his announcement that he would impose vaccine passports everywhere – so this government is much sneakier – instead it will impose their little social credit system step by step – nudging the public bit by bit into accepting their plans for their techno tyranny – as I say … big venues today – supermarkets tomorrow.

This is full on medical fascism – the kind of blatant state-backed descimination one would have only have read babout in dictatorships like Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union.

This pattern of lying has been repeated by the government throughout the last 15 months – deny they have plans for anything so rancid as vaccine passports, then feed us a few crumbs of hope and a ease a few rectrictions here and there … then wham! While everyone has taken their eye off the ball and enjoying a few meager concessions come in with the big changes in policy they promised would never happen …

This is a government that is using the psychological tactics of the tyrant – the bully – the abuser in order to get what they want – vaccine passports for everyone which they have wanted to use this pandemic for since day one – social control system that will then be expanded into every other aspect of your life until you become a slave to a techno fascist state.

This is road to tyranny and this government is declaring war on those who do not tow the vaccine line – without total compliance their tyrannical plans will fail.

This government disgusts me – this is a putrid policy – SHAME ON YOU!

My wife is a fellow sceptic although she believes it’s all incompetence and nothing more. Does anyone here have links to any articles that clearly explain the concept of the social credit system and the reasons why the introduction of the vaccine passport will lead to it being imposed here? Many thanks in advance.

I think it’s imperative that we start to show people what lies ahead for them/us in clear practical terms and not just talk in the abstract of ‘The Great Reset.

Basically they are introducing digital ID initially just for Covid vaccination status which most of the country, having been brainwashed for 16 months, will have no issue with.

They will then keep adding to it, lots more medical data to start with, credit score info, criminal record etc and then eventually we will have the aborted ID card idea where you have to reveal your entire life to everyone.

Also the test and trace app with QR code scanning introduced last year was the initial training exercise to get the population used to having to swipe in to places.

Just ask her whether the Nazi’s conspired to exterminate the Jews or whether it was all just incompetence and officials covering their arses.

And if it was the former (obviously), then when was it clear to everyone that it was a fiendish plan? Not in retrospect, but at the time.

You’re lucky, all my fucking wife cares about is a bloody holiday. I’ve lost a lot of respect. Very sad.

I sympathise KF.

My wife’s decided to get her 2nd jab (that she doesn’t want following a nasty adverse reaction to the first one), but she wants to go to the theatre with friends in October and doesn’t want to miss out. She knows it’s coersion and wrong – but feels her hand is forced.

Tell her to wait till then then… Although the more that get it the less pressure I feel as they might be happy with 99.99999999999999999%

She thinks I’m being selfish for not getting the jabs. I said sorry sometimes principles have consequences.

Nothing signals altruism more than someone who takes a jab because they want to go on holiday or don’t want to be discriminated against. That is proper altruism that is.

My wife is now having to think about being jabbed – concert & wedding in October. I might have to cos this evil git will extend it.

Can’t miss our daughters wedding.

I hope Johnson and his cabal rot in hell.

Stick to your guns.

I’m truly sorry…

Thanks mate

“Are you in an abusive relationship?”

Show your wife this:

This is an excellent presentation of what it’s all about by Dave Cullen. 48 minutes long but worth it. Dates from October 2020 and when I watched it my reaction was to say “Wow. Now it all makes sense”.

https://computingforever.com/2020/10/14/connecting-the-dots-the-great-reset-the-fourth-industrial-revolution/

Then food shops will be out of bounds. Just like 1930s Germany.

Oh, where’s your patience? Its only day 483 of three weeks to flatten the curve!

Surely, even the most dormant brains out there must see where this is going? The Globalists have declared war on humanity.

They did that in March 2020.

Medical Junta Chief Zahawi did not make a u-turn he just lied at the time.

I’m going to use that from now on. Whenever I get caught out on a lie, I’m just going to say I U-turned.

Or use the Dianne Abbott excuse:

“I misspoke.”

Hopefully this is Doris’ poll tax moment?

This is Government by Hysteria. Period.

History will see this for the evil that it is.

These silly little politicians know not what they do.

We must forgive them.

God can forgive them, when they repent.

I’m afraid I’ll havevto keave it to God to do the forgiving, because I can’t.

I’m all out of forgiveness but my revenge levels are high.

In previous times the words were “And may God have mercy on your soul” (before they were executed).

Nah, they don’t get a pass. They need to face full Nuremberg trials, this is NOT WHAT A FREE DEMOCRATIC SOCIETY does to its own tax paying CITIZENS

No chance.

“History will see this for the evil that it is.”

Not if they are the ones who write it.

They, the media and the health professionals know exactly what they do here.

“nightclubs and venues where *large crowds* gather” – large crowds = the new scotch egg.

Be interesting to hear what Farage has to say about this, I just noticed he’s on GB News at 7pm…

Interesting so far, hopefully he wakes a few more up! Sadly they got so many into the jabbed camp and people really struggle to admit they have been fooled, doubling down to avoid embarrassment.

And…. he blew it “one thing we did do right was the vaccine roll-out”.

bound to say it wasn’t he?. He’s on with Graham Brady now- for a pint of ipa

I paused it expecting to be able to resume but it jumped forward, did the horse teethed freedom warrior inspire any confidence what so ever as to a credible resistance or just more hand wringing at the government’s ‘good intentions and tough decisions’?

Vaccination has suppressed the innate immune system in the vaccinated, leading to them becoming an army of asymptomatic spreaders. To insist that people are vaccinated before they undertake ‘mass social activity’ will fuel the fire they have created. The smart thing to do at this point would be to realise their mistake and immediately stop vaccinating youngsters — but they’re not smart.

Indeed, they’re politicians, for whom the right response is always ‘if it isn’t working do more of the same‘ and ‘blame the ones that aren’t doing what you’re telling them‘. Whenever a politician says ‘we need to do more of it!’ always ask if the evidence continues to support their policies.

But the incumbents are still in power, so we’ll continue to have these counterproductive policies and suffer the downstream consequences.

And these downstream consequences will be complete vaccine escape (as the virus now has immense evolutionary pressure towards vaccine escape) and the return of symptomatic covid. What’s worse is that while this would have been benign because so many people now have long lived cellular immunity, the innate immune system of the vaccinated will be suppressed by the very strong and long lived vaccine antibody response (that no longer neutralises covid) and thus covid disease will once again become serious for them.

I’ll add that the right thing to do now would be to insist that the vaccinated maintain a level of social distancing and refrain from taking part in mass social gatherings, but that really would be difficult for the vaccinated masses to accept and would be impossible to achieve.

Very well put.

Many of the big lies used to advance the sinister agenda exposed and debunked.

Freedom Day – the day that keeps on giving!

Well, after that bit of news ordinarily i’d be packing my bags and getting the fuck outta Dodge. BUT I CANT. Can I?

London on Saturday, anyone?

Boris has basically told the youngsters “Just get in the ******* shower!”

The ‘funny’ thing is, it’s not even for a purpose, like saving old folk, anymore.

Noone would still buy that anyway and the HI fantasy is just witchcraft.

It’s just for the sake of it, because we say so, because we ordered the useless poison, because we have some stats to lead etc..

The not so funny thing is that this idiotic spineless youth in particular will still happily walk into these showers.

Could very well apply to today …

There is no possible justification for this whatsoever. This is totalitarianism – pure and simple and whilst 24 hours ago we thought Macron was just mad, it now looks like he was just first out of the traps with a plan to use the power of the state to control everyone. I don’t know who exactly is behind this but they might have bitten off more than they can chew. I think we may have just reached a tipping point of awareness as those who have taken the “red pill” slip into the majority…

They must have had a jolly old time when the G7 summit crew got together in Cornwall recently. Plotting, scheming and conniving who would do what and when.

Thing is, I’m not shocked anymore about what they say and do because I expect the worst from them.

It could be.

Maybe they feel to secure and don’t give a sh*t anymore, maybe they have had to rush things because the vaxxed will soon start to meet their maker or because something else big is concerning them, maybe they want to provoke a violent reaction to clamp down hard and for good.

If we want to stop it, we must mobilize more people, get a general strike going and get the silent good vaxxed people to finally stand up and rediscover their moral compass: they must realize that eventually they will be the next who are coerced and discriminated if they don’t agree with a government policy, like a 3rd, 4th or 5th jab or donating their house to the government.

“The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil people like Tony Blair, Boris Johnson, Macron, Merkel, Sanchez, Biden, Zahawi&co and their criminal discriminatory policies is for good men and women to do nothing.” to paraphrase Edmund Burke.

This needs to be challenged in court.

The judges are cowards -as Simon Dolan found out.

Actually I’m not sure it is cowardice, they have been bought.

So why the sudden change of mind?

There is no change of mind. There is a change òf words.

If the village idiot is serious about this why is he waiting until September? Isn’t that when the emergency licence for the non-vaccine expires? Odds being taken online about how long it will be before he about turns.

Arguably, it has already expired, as the existance of effective treatment for real ‘cases’ is maturing in the trade.

This smacks of complete desperation and panic.

You have to ask: why? Because at some point, it will become obvious who’s had the jabs and who hasn’t by the state of their health.

This is moving swiftly to the endgame.

Desperation and panic? Hardly. They are in the driving seat, followed by the majority, and unquestioned by the media and the opposition other than asking why they don’t lock down more.

Well, if they’re in the driving seat, why behave like this? I think they realise that they are far from being in control of anything.

It’s just a finely judged cocktail of relaxing restrictions and imposing more

I don’t think they will be overly worried about the Big Lie being exposed. They have the complete compliance of the media and most other rich world leaders and organisations

I don’t really disagree with you, Julian; it’s just that there’s nothing ‘finely judged’ about any of this. There’s no proper ‘plan’ or schedule; the psyops people have done just about the crappiest job possible. If the endgame is the jab passport, or id cards, or health id, or whatever, then I could have come up with a better plan last March, even if I’d been on the gin that night.

. . . And on ‘Freedom Day’, what a bunch of (completely predictable) bastards. Will people wake up now?

– Will they fuck.

Johnson is weak and cowardly, stand up to him and do not yield to this tyranny any longer.

What is it with overweight politicians dictating health advice? Or maybe the 70% of the population are obese or fat too?

Get your vitamin D from the Sun this summer. You know further lockdowns. Nothing stopping them now with climate and from dial-a-inner-city riots (via Twitter).

Well, what a complete surprise!

Up is down and all that …

let’s get this right, everyone under 30 has been offered this injection, one third clearly don’t want it. This is coercion, this is criminal, why do they think his is ok? (story on Farage GB News programme now btw)

ps anyone for an illegal rave?

Lets offer Boris a whisky and revolver…

If he doesnt reply lets just keep offering him it.

So they open up just for a while so they get a taste again of what they will lose if they don’t take the poison.

Sick fucks

I thought that there was a big anti lockdown march in London today.

I assume that it doesn’t count as news to the MSM.

There was – go to “Subject Access” channel on Youtube or “We got a problem.”

Was reported sin the Daily Mail although with typically biased headline!

Anti-vax louts lob bottles at police during clash outside Parliament

https://mol.im/a/9802489

This looks like reasonable policing…:

Maybe the little old lady(?) cowering poked the poor officer with her arthritic hands.

I think Officer U 2777 is in a tiny bit of trouble…..

What a thug. The police is full of testosteroned types all full of steroids and machismo. There are good police but this is unacceptable. I hope Officer U 2777 is sacked.

There are no good members of an organisation that is so corrupt; all are guilty by association, notwithstanding that good people are un likely to want to join such.

Oh it was on GB News just now. Maybe that woman was right… she was heard anyway.

How does this work for musicians or people working the venues? No-one seems to be talking about that. Lots of bands would’ve booked tours for later in the year, I presume many of which won’t be fully jabbed?

What if you are a nightclub owner who hasn’t been jabbed, does that mean you can’t access your own business premises!!

Today, the government lost the argument about vaccines.

Whatever opinion a person has about the vaccine is now irrelevant. This is no longer about health. It is about coercian and oppression.

Under such circumstances I would advise people not to have any vaccine or medical treatment.

I don’t think they were ever winning the argument

Covid was never an emergency that justified short-cutting trials, and there was no attempt to investigate alternative treatments

or Antibody test prior to jabbing.

It’s about getting as many jabbed as possible.

I would advise people not to have any vaccine or medical treatment.

Surely some mistake? what about e.g. statins?

I’d agree if you said what about aspirin, statins are poisons

Daily aspirin also has serious side effects, tinnitus that could develop into deafness. Taking good quality fish oil also keeps blood thin and has other health/longevity benefits

I dropped statins almost two years ago because they were making me poorly.

I mean in the context of coercion. That is, have a treatment if you are rationally persuaded about it: in a coercive environment I question if that is possible.

Go away corporal.

I’d like to club some sense into him.

I hadn’t realised that Zaharwi spelt complete bastard. This is the thin end of the wedge towards what’s happening in France. All planned and agreed beforehand.

I am phoning my GP tomorrow for a medical exemption and I urge all of you to do the same. I cannot take this vaccine, the anxiety and stress that it would impose upon me would be to much to bear. No more fucking nice guy, I’m going in guns blazing and will not be told that I am not medically exempt

If they want a war they can have one.

I was wondering if I could be declared a hypochondriac – seems logical when you don’t want treatment to make them think you want treatment for everything….

What counts as a medical exemption?

HIV, clotting issues….

TBH though, that’s irrelevant, even you are exempt you will still have to have the apps and present them on demand, this is the goal and I’m not taking part.

I don’t care whatever crap my doctor wants to say I have, suicidal tendencies brought on by mandatory vaccination through coercion by the state??

There is no such a thing as a medical exemption -it is just an exemption that you declare yourself

Did we really think the tyranny was going to end July 19th?

We went to a massive anti lockdown demo in London ignored by the evil complicit Daily Telegraph. THIS IS THE EVIL THE MEDIA IS COMPLICIT

TRY THIS https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u0N_VzOVkXs

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GCI0NMgVfPk&t=1247s

Stand in South Hill Park Bracknell every Sunday from 10am meet fellow anti lockdown freedom lovers, keep yourself sane, make new friends and have a laugh.

Join our Stand in the Park – Bracknell – Telegram Group

http://t.me/astandintheparkbracknell

Home Schooling – Ex-Primary School Teacher on Resistance GB YouTube Channel:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kZ5oS2ejye0

https://www.hopesussex.co.uk/our-mission

‘….the capriciousness of the communist oppression was based on fear……’

Socialist Europe and Revolutionary Russia: Perception and Prejudice 1848-1923, Bruno Naarden

No parliamentary debate, policy made, and unmade, on a whim…….

Voters, particularly young voters, do not forget this stuff:

‘In the last stage of the Niemietz Cycle, the failures become too obvious to ignore or explain away, and the country is demoted to “not real socialism.” Western intellectuals fawned over Stalin’s experiment with socialism, and only after it became a conspicuous failure did we learn that “It wasn’t actually socialism; it was Stalinism, and if only Trotsky had been in charge instead of Stalin….”

And they react, one way or another:

‘….people vote for freedom and against socialism in overwhelming numbers.’

https://www.aier.org/article/cuba-demoted-to-not-real-socialism/

Chesham and Amersham, Batley and Spen…………

This is a long game….but the issue is not in doubt

Any pressure the government is feeling from public opinion seems to be pushing them towards more evil oppression, not less

The vaccine passport stuff and jabbing kids are concessions to the bedwetters and zero COVID loons

I am sure that this is against basic human rights laws – what about people who have medical conditions which mean that they cannot be vaccinated? – Will anyone challenge them in the courts (although the courts do seem biased in favour of caution vs freedom)

I do not blame young people for avoiding the vaccines – the harms vs benefits for them are far from clear – https://wintoncentre.maths.cam.ac.uk/news/communicating-potential-benefits-and-harms-astra-zeneca-covid-19-vaccine/

As I just posted below, I think that’s the wrong fight:

‘That’s irrelevant, even if you are exempt you will still have to have the apps and present them on demand, this is the goal and I’m not taking part.’

indeed that’s what they want – not taking part is the way forward

Is there anything, ANYTHING, that the government says that can be trusted? Have they kept a single, one, promise yet that they haven’t done a complete reverse ferret on??

They are knowingly, and deliberately pushing people into having a potentially dangerous vaccine, which most don’t need, just so they can impose a digital passport, and vaccination of the entire population, whether people want it or not. They’re not being given a proper choice.

Looks like ‘large venues’ are going to suffer by the majority if freedom lovers who aren’t going to dance to the Governments tune.

Boris’s poll tax moment.

P.S.: what about all those who’ve had a serious adverse effect after their first jab, and cannot, will not risk a second one??

They clearly don’t care about those they kill and harm, just so they can push vaccines on everyone.

They clearly don’t care about those they kill and harm, just so they can push vaccines on everyone.

That’s always been the plan and that was clear, even before the vaccines were supposedly invented. It’s all about depopulation and they have got virtually all of us scheduled for an early exit.

Bill Gates has been pushing his depopulation by vaccine agenda for nearly two decades and yet people still allow themselves to be injected with his terminator vaccines. The vaxxed almost deserve what’s coming, but the rest of us don’t.

End of my musical career then.

Again.

Same here. Fuck them to hell. I’m taking something back for what they have taken away, that is my promise

Yaas, but my pitchfork’s been in the ack room it’s going rusty. . .

Bloody phone – that would be ‘back room so long’ . . .

Seems it’s already the end of Eric Clapton’s too for doing the exact opposite…

Can you play without electricity? If not learn to play an instrument like yours that is mechanical. If so, the world is your oyster.

Give it a week and the mission creep will start.

Soon it will be no access to churches, health services, public transport.

Absolute certainty.

Oh, go and boil your head. Defeatism leads to defeat. That is an absolute certainty.

Come on Annie, you can’t seriously believe they will stop at nightclubs?

Sometimes Annie you make an utter bloody fool of yourself.

There is nothing defeatist in my statement it is simply my interpretation of the situation.

I hope my interpretation is wrong but the past sixteen months assures me it won’t be.

yes look a t the french protests now and greece and england fo r over year, gives me hope , still trying to find one near me !

will hav e to start own very small party of one protest

and i have a new fellow resistant friend so will be at least 2 of us

As they whittle away at the resistance, I’m starting to worry about the endgame for the last few percent. Cattle trains and work-camps; confiscation of property; seizure of bank accounts? I don’t feel very hopeful today.

I am inclined to agree unfortunately.

BTW, we will both get both barrels from Annie when she reads your post.

as bad as it sounds now we must be positve that we will win. churchill is always my inspiration !

We will win – it’s just how long it takes and how many lives it costs that worries me

The social services will remove your children if you refuse to be ‘vaccinated’. The new prisons are being built for ‘the awkward ones’.

I didn’t realise they were building prisons to house 5 million people and growing, they must be ginormous.

This means war. Time to drag these out on to the street. De Pfeffel should be very scared when looking at what is brewing in France. The British Government are tyrannical murderers and are legitimate targets for removal by force in my eyes.

I think any action is now legitimate

Legitimate, urgent and absolutely fucking necessary…

It’s the only chance we have, or else we will burn on the BillGates altar to global warming.

Yes, the government declared war on its own people some time ago when it signed up to the Bill Gates depopulation by “vaccine” agenda. The vaxxed are effectively already on the way to the mortuary and soon it will be the turn of the unvaxxed to make the same trip. They want us all disposed of, and so there is little to lose. Resistance is the key to survival.

Wishful thinking.

This is like the occupation of the American west.

Those of us who want to live with natural immune systems are the native savages who are about to be overrun by a new, more modern civilisation that relies on artificially created immunity.

We are individually stronger, But they are more organised and have strength in numbers.

We are the ones in line to be “depopulated”

Yes, the government wants to see what happens in France. If things go badly for Macron then eugenicist Boris and his bunch of murdering thugs will regroup, but they won’t abandon their plans, until we make them.

Most people being hospitalised and dying are double jabbed.

The vaccines don’t stop spread. Don’t stop disease in the vulnerable.

The only argument left, is that hospitalisations will be reduced by jabbing the young. The young haven’t and won’t be filling hospitals as covid cases, they’re not the vulnerable age group.

There. Is. No. Argument

Anyone got a list of demonstrations?

A list of the addresses of members of SAGE would be more use.

The first thing that needs to happen if young people have any balls is that we should see the biggest fucking illegal rave the world has ever seen this weekend.

Rave Against the Machine

What about the medical profession?? Are they going to stand silent whilst a medical intervention is imposed upon people who have no wish or need for it? And MPs are they willing to stand by and let this happen, a slippery slope indeed, where is it going to end??

Um, yes.

Well I’m not letting my GP away with it, I want him to look me in the eye ( if I can get a fucking appointment) and squirm in his chair whilst he tells me the reasons why he thinks this should happen.

I think we really know what they have in mind. It’s not looking too good. Most government ministers will have a date with a lamp post before all that long.

The medical profession was in the position in March last year to take a stand when The Fat Dictator imposed the first lockdown after Covid19 had been downgraded and basically classified as no worse than ‘flu. To their shame, they, the only people with the authority to refute the government hype, said nothing.

They have further reduced their standing by not speaking out against the main driver of the scam, the worthless Drossten PCR test.

That they are complicit through their tacit support for mass vaccination is the final nail in the coffin for any trust we should have in this bunch of shysters.

Yes, and if they are like my GP they will simply hide in their homes on full pay while refusing to see any patients.

Still not convinced then Toby; how much further does this shit have to go until you accept this is not the work of bunglers or incompetents but a committed assault of the British public?

Yup. Never was not knowing what they are doing.

they know exactly what they are doing with their censorship, banning treatments that will prevent deaths such as HCQ, Ivermectin, vitamin D – how can you send a sick person home and tell them to come back when they can no longer breathe?

This is a declaration of war by stealth on the people of England.

Just scanned through the current 157 comments. I could uptick just about every one.

Has Zahawis children and wife had the injections? You would think this man having being raised in Iraq he would have turned away from the Sadam Hussein style of leadership, instead it would appear he has fully embraced it.

I know this will be controversial but I don’t think a man from a country we went to war with very recently should be in government. Can you imagine the reaction if a German had been in government in the 1950s.

Excellent choice of new name for this site, and it’s a good slogan as a subtext, too. “Daily Sceptic” might just bring in some of the as-yet unconvinced that lockdowns and restrictions are effective of justified.

There are plenty of sceptics out there, in a general sense, but so far “lockdown sceptics” have only been a small subset of these. The change of name means it might just appeal to people who are critical thinkers in general but have not started thinking critically yet about the government’s approach to the pandemic, this approach having been elevated by propaganda to quasi-religious status.

“Question everything, Stay Sane, Live Free”: This got me thinking – If we are where we are by virtue of a coordinated plan of scare propaganda, then theoretically the reverse must be possible. If a biological epidemic can be addressed by vaccinations leading to antigens, then could an epidemic of fear and hysteria be neutralized by applying the opposite of what created it: An “Anti-Propaganda” campaign, or more accurately, an Oppositional Propaganda campaign?

Slogans such as “Question Everything” can be used to combat messages such as “Follow The Science”. “Stay Sane” is a good antidote to “Stay on Alert” (for new variants!). And “Live Free” is a good medicinal remedy to “Stay Home, Save Lives”.

Now that “Freedom Day” has arrived (if only chronologically if nothing else), and Fear has been drilled into the darkest recesses of our collective psyche, we now need to drill the message of Freedom back into people, and perhaps that can be achieved through publicizing messages of positivity and hope.

If fear has been weaponized against us to keep us in state of compliance, the deep-set desire that still burns in people’s souls to “Live Free” can be used as a shield, or even a counter-weapon.

Excellent post and I agree with you.

Very good

Using the most conservative estimates of vaccine safety, this mandate will kill approximately 300 18-30 year olds. That’s a nightclub full of kids with their whole lives ahead of them.

It won’t just kill them. Boris has ordered their deaths.

But if just one 102 year old granny gets to spend another couple of moths drooling in a care home before dying anyway then it will all be worthwhile!

From The Guardian (my emphasis)

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jul/19/how-will-englands-domestic-covid-vaccine-passports-work

Could pubs and other venues be included?

It depends. At the Downing Street press conference where he unveiled the plan, Boris Johnson was asked if the domestic passport scheme could be extended to people going to pubs. Johnson said he did not want to “get to the situation where people are asked to provide papers to go anywhere”, but did not completely rule it out. They are deemed appropriate for settings with the three Cs – “closed spaces, crowded places and close-contact settings” – the press conference was told.

“The Three Cs” – That’s Vallance, Bunter and Whitty, isn’t it?

So they are a definite then.

Can’t people see?

A fuckin infection with 0.15 % fatality rate and it’s “papers please” everywhere. Restrictions on everything.

The Scam is so blatant and people apparently still can’t see it.

Unbelievable.

Some of the best cons are the ones that are so obviously a con…… of course the fact the 99% of the uk population are brain dead zombies with absolutely no critical thinking skills or ability to think independently helps.

Would it be considered racist to wonder why an Iraqi called Nadhim Zahawi thinks he has the right to decide what is best for English children? Walking on eggshells and trying to tiptoe around it but there’s something really unsettling about this.

In the interests of fairness, whatever one might think about him, or his policies, he is a British citizen:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nadhim_Zahawi

Being British isn’t citizenship or where you are born, it’s having British values that make you truly British. That is what I am getting at. Not that any of our politicians have British values. (Sir Desmond, Graham Brady, Richard Tice and a few others excepted)

Thanks for the wiki link – he’s an utter cunt and should be strung up:

Zahawi claimed for 2012/13 a total of £170,234 in expenses, ranking him the 130th highest out of 650 MPs. He explained in his local newspaper Stratford Herald that the “vast bulk” of his expenses was on staffing costs.

In November 2013 Zahawi “apologised unreservedly” after The Sunday Mirror reported that he had claimed £5,822 expenses for electricity for his riding school stables and a yard manager’s mobile home. Zahawi said the mistake arose because he received a single bill covering both a meter in the stables and one in his house. He would repay the money though the actual overcharge was £4,000.[28] An article in The Independent also drew attention to the large number of legitimate but trivial items on Zahawi’s expenses.

Yes, I described him as such in an earlier post. It’s just that, in my view at least, once British citizenship is attained, that should be the end of the matter. There should be no suggestion of a two-tier citizenship differentiating those born here from those born elsewhere. However, it’s a bit of an off-topic debate, but it does relate to the notion of freedom in its broadest sense.

I agree, in that there should be no two-tier of anything. I don’t trust the guy though, he’s a crook through and through.

Agreed.

But he’s part of the cabal pushing a two tier citizenship!

The man is an out and out criminal and in a just world he would be in jail, not in government.

To be fair £170k somehow doesn’t look that bad, when I’ve recently found out my MP claimed just a tad under £200k. during a year in which we spent (almost totally) under severe restrictions — so where the hell did she go?!

Well I know where she should go….and that’s straight there without collecting £200….

I don’t think his citizenship or his race are overly relevant

The problem is the political allegiance- an allegiance shared by a variety of government and opposition leaders and MPs from a variety of backgrounds

Upvoted you there, you tried!

Thanks

Lol

A man from a country we went to war with very recently should be in government. Can you imagine the reaction if a German had been in government in the 1950s.

Well the Russians and the Yanks snaffled all the German rocket scientists after the war. It was said that the reason the Russians got into space first was that their Germans were better than the Americans’ Germans

So if we are Now going to have medical apartheid in this country can the unvaccinated stop paying their taxes? We can’t access society so why should we pay towards it?

U-Turn ? Don’t make me laugh, this was always coming, they just had to pretend long enough to get everything in place.

If Toby and his ilk still think it’s simple over reaction at this point then they are lost.

If i’m barred from everywhere in town I guess i’ll not be paying my council tax for starters.

Just so that this isn’t buried soo deeply in a reply: It seems someone again managed to reduce little Boris to frightenend shivers by telling him scary stories of what happenend when they opened … nightclubs (gasp) abroad.

Could the party this creature claims to belong to please get rid of this laughable caricature of both a man and a British conservative? Stupidity and cowardice aren’t exactly “leadership skills”.

If he’s scared of that, imagine how scared he’ll be of what is coming for him now

You’ve got to wonder which planet these twats hail from. What the hell did they expect to see in a nightclub – a large crowd antisocially distanced, all standing 2 metres apart and wearing face nappies, and dancing that bloody stupid macca-something-or-other where you stand still and wave your arms around. Stroll on!

These clowns have never set foot in the real world, if they did they wouldn’t last 5 minutes.

Little Boris? Frightened shivers? He’s presided over it all from the start. It’s his show.

Something else from the press conference: Van Tam was asked which restrictions could possibly be reintroduced in future. His reply was (paraphrase) “That’s for SAGE to decide.”

They like to hide behind SAGE but it’s done with the backing of the PM

Everybody’s riding roughshod over a PM who is constantly being forced to do embarrassing climbdowns and U-turns at a moment’s notice, sometimes changing his supposed stances from one day to the next. The leader of the so-called opposition is positively gleeful that keeping to egg on his character for still not being harsh enough on the populace and thus being responsible for “countless” deaths of people who – statistically – would have died anyway will positively crush the man, and that’s all his own clever conspiracy and “done with his backing”. Sure.

In programming, there’s a concept called “duck typing”: If looks, walks and quacks like a duck, then it must be one. And this certainly applies to Johnson.

Yeap, if it looks like and sounds like an authoritarian dictatorship them that is what it is…….

Albeit Bozo is only a puppet for masters elsewhere.

He’s no more in charge than I am.

It’s an act

The point of your reply was?

I’m not so sure. He is weak and lazy. There is someone else/ some other entity pulling the strings, he is just a puppet.

I am sorry but that really is a “No shit Sherlock” comment.

Yeah true, I apologise here and now for stating the blindingly obviously.

No he’s a fat ineffectual puppet – a figure of ridicule with a hundred fingers up his arse directing him whichever he goes. He is destined to be remembered as fondly as Qusiling, and even a weak version of him.

Trawl the depths of your intellect, as you have, you found yourself feeding on the sterile filaments of outraged disappointment yet were incapable of forming a coherent way out of your plight.

Good effort at the Branch Member outrage, however, …

Has this been put up here? Arrest of Wills (journalist)?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u0N_VzOVkXs

Who was the guy being viciously assaulted by the Scum?

None of what they stated here makes medical sense or is true, least of all van Tam’s shed analogy.

This policy change confirms my long held suspicion that this is all orchestrated internationally.

Some countries are briefly allowed a few more freedoms or earlier openings, only to be the frontrunner in introducing a new draconian measure, here the abolition of the test alternative, which can then be introduced elsewhere.

Tyranny 101.

They know exactly how to establish it, are in it for the long run and have a lot of time, see Julius Ruechel’s essay yesterday.

Can we stop it and if so how?

People don’t doubt the consensus, yet- there is no Ceaucescu booing moment in sight yet. But more and more people are personally impacted by the lies, i.e. the infection after getting jabbed, so that is a promising angle.

But short of millions hitting the streets and going on strike, or of millions dying soon, it doesn’t look like we can stop it.

It will then likely only end by itself once the money has run out, but that can take another while.

Wait till inflation hits and mortgages go up and people realise what they have done. No power grab in history has ended in anything other than mass bloodshed. No attempt at social engineering has ever gone the way it was planned. Remember the Nazis came to power because they were useful for the ruling classes in removing the communists. The plan was to move them on after that.

There’s a plan, but it isn’t going to go the way it’s meant to. War is coming make no mistake.

Soviet Russia lasted a few decades

The CCP has managed 75 years

And did they both achieve their goals without bloodshed? There’s about 20 million people who’d disagree. I didn’t say who’d win, I just said there would be blood.

Yeah I agree here. I don’t think they can achieve this without harder pressure.

Well, true, there was bloodshed at various points, and lots of it. Covid so far has meant it’s not been needed.

My interpretation too.

This is a war and wars never go according to plan. Never. So no matter how many ways they have gamed this they will have missed something which will disrupt them.

I hope it is enough for us.

Wars always go according to plan and are never lost by the victors. Sounds trite? Point out a war that was won unexpectedly by the inferior belligerent. Don’t offer battles or campaigns, confine yourself to wars. Wars are won by those who plan for them and are ruthless.

If Hitler were around today he would not need to go to the trouble of sending an army to defeat the UK. Instead all he would have to do is buy off the media then convince them to use all the shabby tactics we have seen displayed by them over the last 15 months to convince the UK public that that season’s flu/bad cold was in fact the most deadly disease as yet kwon to man, with a close to 100% fatality rate a near certainty that anyone catching it would suffer the most horrific agonising death as yet known to man. Throw in some horrific films from Covid wards (all films of hospital wards are horrific, films of people seriously ill from smoking, cancer, heart attacks, stokes, traffic accidents and falling off ladders are all equally horrifying) and some bodies of people who may or may not have died of Covid accompanied by some scary music and hey presto, the entire UK population will be under your complete control forevermore.

As we have seen over the last 15 months they will happily and without question let you imprison them with no definitive end date in sight, destroy their livelihoods, ban religion (well certain ones anyway), stop them seeing family and friends, stop them have any form of enjoyment, gag them, stop them leaving the country, stop them travelling from one part of the country to another, stop them meeting lovers, ban elections and inject them with whatever experimental concoction you fancy. If any of the very tiny minority of the population with any critical thinking skills start to question what is going on then simply throw around some horror stories about a new variant or long Covid and you will have complete control of the population forever.

This government needs to burn!

Does anyone have a figure for how many 18-30 have died in 2021 from Covid? Looking to compare to the estimated 300 Boris has ordered to die by vaccination.

In the UK of the total population, 20% are under 16yrs. Of the rest, about 12% are not vaxed first dose. I know its tempting to say there is going to be a revolt against these moves, but lets be realistic, there really isn’t. Not anywhere in Europe. There are some developing nations that have not embraced the vax route, but of the developed world I can only think of two, and then only some of one of them. Japan has not despite a very aged population. They have a very antivax midset, I think the latest number was 18%. And then 50% or so of the US has not followed a vax route, specifically red states.

So unless you are planning an escape to Japan ( impossible) or a red state of the US ( bloody difficult unless you have a $1m to invest) then you will remain living in a nation which is overwhelmingly vaxed and increasingly be a second class citizen.

I say this as one of the unvaxed. We need to work out how to survive initially and then hopefully how to subvert the majority. I have absolutely no answers or suggestions for the second of these, I read incredibly optimistic views of how it may unfold, but they seem completely unrelated to present experience. And I do not have the energy or skills to become ‘self reliant’ in a completely off-grid life.

I have come to the conclusion that the only way to survive is use of cunning and trying to use the inadequencies of their systems to plot ways around them. However if absolutely everything comes down to a vax certificate including shopping for foodstuffs, the only route will be to pick the least worst option which currently might be Novovax of Valneva, neither of which use ‘live’ contents and are more like HepB or Flu vaccines.

Fighting a global totalitarian biotech regime will take longer than my lifetime or that of my children. This is truely distopian.

A fairly large percentage of those who marched in France were vaccinated. You can’t assume that everyone who has the vax supports totalitarian government, it doesn’t work like that. My fully vaxed band mate has been emailing me saying if he still had his shotgun licence he’d shoot Boris! Even the lead story on the BBC has most upvoted BTL comments saying this is a step too far.

”A fairly large percentage of those who marched in France were vaccinated”

Nice thought, how the hell does anyone know that?

I lived in France for two years, I know a lot of people there. Several on the marches. It’s only anecdotal but that’s the picture I got.

I read somewhere that the French are the least vaccinated!