There follows a guest post by Lynne Sash that’s a response to Toby’s FAQs on Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

I have been a daily follower of this site despite having left the U.K. permanently two and half years ago. Even living in comparatively sane red-state Iowa, it was helpful to know that we weren’t alone in wondering what possessed politicians to damage their societies to no purpose, and I welcomed the site’s transformation into a more broad-based sceptical platform. But I was disappointed in Toby Young’s February 28th article about the war in Ukraine. It struck me as a retreat from scepticism at time when we very much need to press on. I’d like to focus on one section of the post relating to Russia’s view of NATO expansion.

Overall, Young seems inclined to analyse this situation by making moral assessments about who is good and who is bad, but in this context booing the villain is unhelpful. Despite the emotional tenor of our times, geopolitics is not a morality play. These decisions are only about the strategic interests of the country you are defending. To paraphrase Lord Palmerston, there are no perpetual friends or enemies, only perpetual interests. Our interests are not the same as those of our adversaries, so we either need to find a way to reconcile them in a satisfactory manner or prepare for an eventual war.

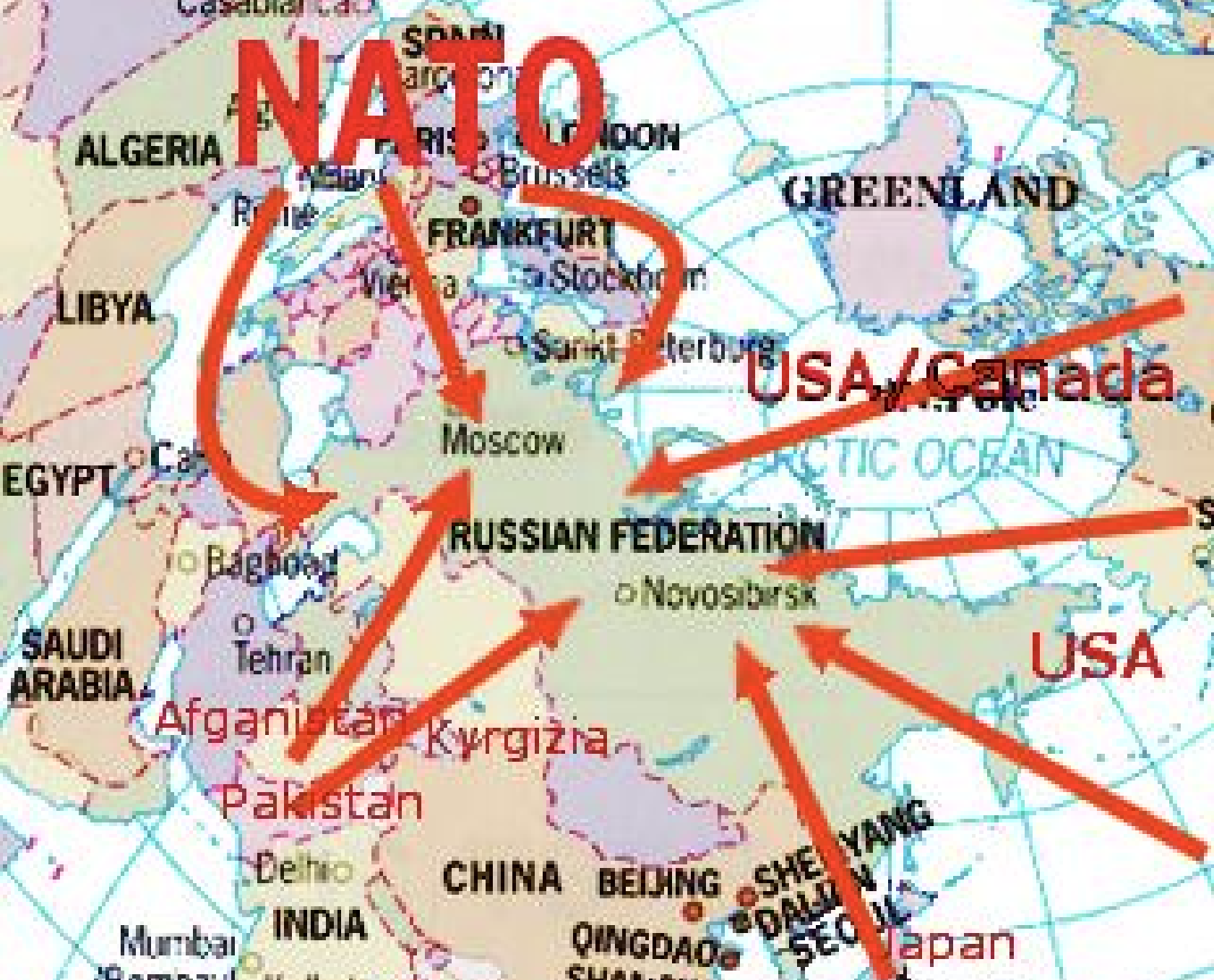

This is the primary source of our trouble with Russia today. For the last 30 years the U.S., and by extension NATO, have failed to acknowledge that Russia has legitimate interests in its near abroad. The Georgian conflict, which occurred after discussion of Georgia joining NATO, was a good example of this. Faced with a potential NATO member on its southern border, it was always likely that Russia would see the breakaway entities of Abkhazia and South Ossetia as buffer republics with whom it could cooperate. Georgian entry into South Ossetia meant that the Russians did cross the border while pushing them back into their own country. It is reasonable to ask what role foreign advisors played in this conflict, given that it was an opportunity to gauge the nature and strength of any Russian response.

Discussion about Ukraine joining NATO was even more consequential. Not only is Ukraine a large country directly bordering Russia, the Russians were leasing the naval base at Sevastopol in Crimea, which is the home of the Black Sea Fleet and their primary warm-water port. Although the lease was extended by another 25 years in 2010, a NATO-allied Ukraine would eventually make this position untenable for everyone given that, in the event of hostilities, NATO would certainly neutralise the base as a matter of urgency. At this point, detaching Crimea from Ukraine would have become a strategic priority for Russia, hence the 2014 referendum which achieved this without bloodshed but did not resolve the problem of a potential NATO force on Russia’s western border.

NATO forces in Ukraine have always been a red line for Russians. George Kennan knew this, and nothing has changed. The Russians, quite reasonably in my view, regard hostile NATO troops on their longest western border as an existential threat. Why, then, has the West continued to toy with this idea when it is bound to lead to conflict? My thinking is that the West has been hoping that continuing or increased economic sanctions would weaken Russia to the point that it could do nothing to oppose Ukrainian membership of NATO. But that hasn’t worked.

There’s a comparison that’s been made frequently since the war broke out that I think is reasonable and instructive. If Russia engaged in the kind of activity in Mexico as the U.S. has in Ukraine, the U.S. Army would have been on its way to Mexico City long ago. There would be no talk of sovereignty or democracy, only the hard reality that Russians could not be allowed to expand and strengthen their presence on our border. And we would, for once, be right. It is not in the interest of our national security to permit it.

Russia aside, it is not at all clear that continued NATO expansion is beneficial to its member states. The original strength of the alliance lay in the fact that it had a limited membership agreed on the defined objective of containing Soviet expansion. But the world has changed since 1949, which has given rise to two problems that haven’t received enough attention. First of all, if NATO is still a defensive alliance, who or what is it defending itself against? The spontaneous response to this would be to identify Russia as the adversary, but this in turn implies that the existence of NATO itself casts Russia in the role of perpetual enemy. Unsurprisingly, the Russians have worked this out for themselves and concluded that their own national interests are likely to play out against a background of low-level Western hostility.

The other problem is the divergence of interests amongst NATO members themselves. In 1952 it made sense to include Turkey in the alliance: the country controls access to the Black Sea and its sheer size made it a regional power. Seventy years later it’s harder to see how our interests are aligned with those of Turkey. The renewed prominence of Islam in Turkey’s political calculations sets it at odds with its Western neighbours. Similarly, further NATO expansion risks drawing in countries whose own perception of their national interests may involve relying on NATO support for actions that were unanticipated by larger allies.

This issue becomes more acute as we consider membership for the larger countries bordering Russia. How precisely is our own security enhanced by including Georgia and Ukraine in NATO? This would certainly antagonise Russia while committing us to the defence of countries which, to speak frankly, have an axe to grind with their large neighbour. It is entirely possible that a limited regional conflict could be incited in the expectation that it would draw in the rest of NATO, as required by Article 5, and involve them in a direct attack on Russia. The unwieldy nature of an ever-expanding NATO carries significant risks that are not widely appreciated.

Where does this leave us now? The short answer is that we need to stop digging. Western policy decisions have contributed enormously to this crisis, and we need to understand and accept that if we intend to change it. As a matter of urgency Ukraine should be recognised as a buffer state between Russia and NATO allies. There should be an agreement of no NATO membership for Ukraine and preferably no EU membership. The ideal outcome would be international acknowledgement of both Ukraine and Belarus as non-aligned buffer states with no foreign military presence. It is possible to argue that this rewards Russia for its invasion, but given ongoing U.S./NATO provocation that refuses to even acknowledge Russian security concerns, how are the Russians to legitimately respond? The U.S. and its allies seem to arrogate to themselves the right to do a lot of things in the interests of national security that they won’t then let other countries do. This isn’t tenable, and if it isn’t addressed honestly by the West it is going to continue to cause resentment.

I have enormous sympathy for Ukrainians and I hope that, if our homes were under attack, we’d fight with as much determination as them. But while I don’t approve of the invasion, I do think it was inevitable. If we’re going to poke the Russians, they will poke back or else accept that the West has a free hand in their sphere of interest and, eventually, in Russia itself. We also have to ask ourselves whether the West is wasting whatever strength it has to the benefit and encouragement of China. Taiwan aside, if Russia is squeezed to the point of collapse, the Chinese are just across the Amur assessing the resource base of Siberia and the Russian Far East and are likely to be capable of denying the West access to these resources if they choose. I doubt the Hubristic Class has thought this far ahead.

Finally, I was disappointed to see Toby Young suggest that sceptics should take a certain view of this crisis. The sceptical way is the dispassionate way: we should be clear about our own objectives and understand how to manage adversarial relationships to achieve them with a minimum of conflict. It is very difficult to avoid being sucked into the contemporary emotional vortex – I’ve lost track of the number of times I’ve screamed ‘Are you fucking kidding me?’ over the past two years – but it solves nothing, and neither will the simple solution of defining Putin as a bad guy. The adults left the room long ago, so let’s at least try to provide a mature perspective that is not driven by the overriding need to be publicly perceived as Good People by the megaphone-holders of progressivism.

Now you must excuse me while I return to my prepping activities in anticipation of societal collapse.

After a degree in International Relations, Lynne Sash worked in the U.K. for 30 years providing international research and strategy consultancy services for the engineering, defence, and healthcare industries. In 2019 she returned to Iowa, where she is assembling a library of ‘cancelled’ books.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.