In his testimony to the Health and Science select committees, Dominic Cummings heavily criticised the Government’s handling of the pandemic. One of the biggest mistakes, he argued, was the failure to impose border controls:

Obviously, we should have shut the borders in January. We should have done exactly what Taiwan did… Yes, that has some disruption, but the kind of cost-benefit ratio is massively, massively out of whack, and at least it is worth a try, like lots of things. At least you try it … If it doesn’t work, you still have the whole nightmare to deal with, anyway.

However, Cummings somewhat absolved the Government of blame on this score – at least with the respect to the period before April – insofar as all the scientists were advising against border controls:

He was told, and we were all told repeatedly, that the advice is not to close the borders, because essentially it would have no effect… you cannot blame the Prime Minister directly. That was the official advice. The official advice was, categorically, that closing the borders will have no effect.

Cummings’ testimony is consistent with the evidence from SAGE meetings in January and February of last year. For example, the minutes of a meeting on January 22nd record that “NERVTAG does not advise port of entry screening”.

Another factor Cummings mentioned, as to why the Government didn’t impose border controls, is political correctness:

At this time, another group-think thing was that it was basically racist to call for closing the borders and blaming China, the whole Chinese new year thing and everything else. In retrospect, I think that was just obviously completely wrong.

What should we make of Cummings’ argument that border controls were at least “worth a try” in January? On the face of it, the argument seems very reasonable. In the best-case scenario, we could have achieved the same outcomes as New Zealand – zero excess mortality and just a small decline in GDP. And in the worst-case scenario, we’d have been in the same situation as otherwise.

However, the latter outcome – being no worse-off – isn’t necessarily the worst-case scenario. A potentially even worse scenario is if we’d contained the virus until the autumn, and then experienced a major epidemic at the same time as the NHS came under its normal winter pressures.

This was in fact one of the reasons why scientists were initially advising against both border controls and lockdowns. Cummings was apparently told:

Even if we therefore suppress it completely, all that you are going to do is get a second peak in the winter when the NHS is already, every year, under pressure … If you try and flatten it now, the second peak comes up in the wintertime and that is even worse than the summer.

This argument should not be dismissed out of hand. Several of the European countries with the highest death tolls – Poland, Bulgaria, Czechia – are ones that escaped the first wave, only to get clobbered in the second. (Of course, there may be several reasons for the high death tolls in these countries; I’m not suggesting the epidemic’s timing is the only one.)

Deciding whether to impose border controls therefore represents a trade-off between the benefits of buying time and/or achieving containment versus the risks of postponing the epidemic until the winter.

Comparative evidence suggests that achieving containment would have been a tall order for the U.K. Although some Western countries have successfully contained the virus, they are all geographically peripheral nations with relatively low population densities and few ports of entry. Britain has the advantage of being an island, but it’s larger, denser and more connected than most of its peers.

Indeed, there are several countries that failed to contain the virus despite imposing early border controls. To identify when countries introduced restrictions on international travel, I will rely on the Oxford Blavatnik School’s COVID-19 Government Response Tracker. And for charting the epidemic’s trajectory, I will use the daily number of deaths per million people, as reported by Our World in Data.

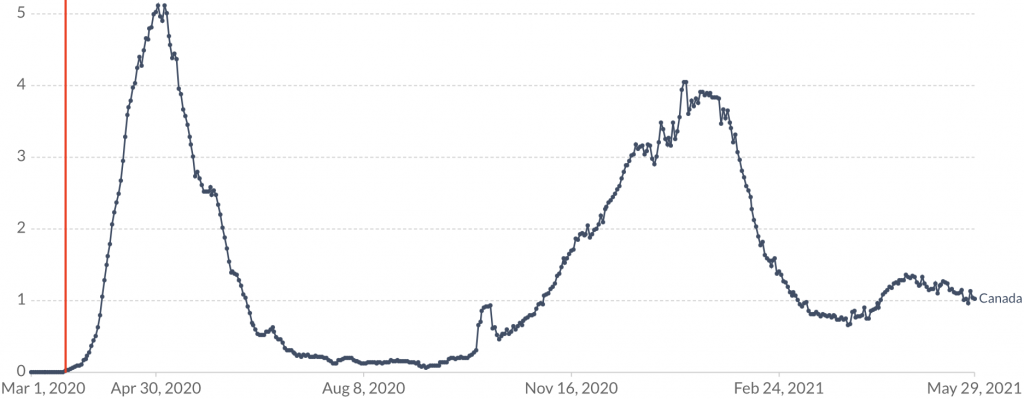

Canada imposed a total border closure on March 18th (see chart below). This was too late to prevent the first wave. Yet the policy has been in place ever since, and it did not stop a second wave from emerging in the autumn.

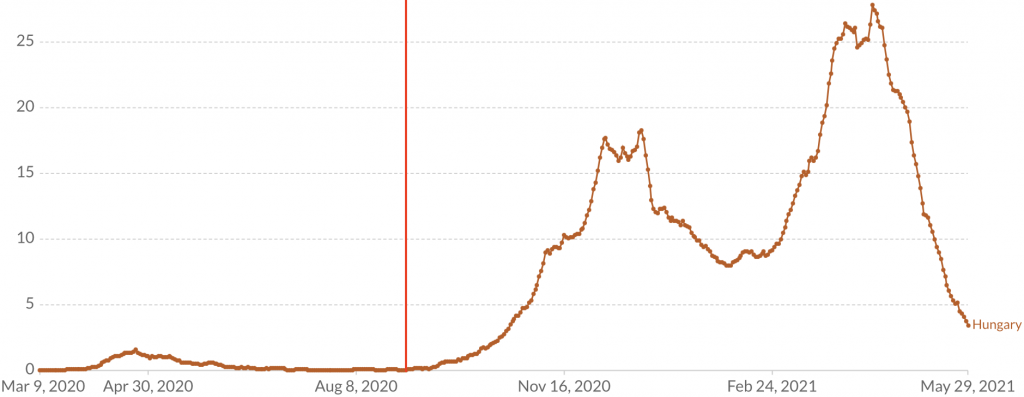

Hungary imposed a total border closure on September 1st (see chart below), but this did not prevent two major epidemics from burgeoning in the autumn and the spring. Note: the Blavatnik School rates countries’ travel restrictions on a 0–4 scale (with 4 corresponding to a “ban on all regions or total border closure”) and Hungary’s rating hasn’t gone below 3 since March 9th 2020. (By comparison, South Korea has never had a rating of 4.)

Argentina imposed a total border closure on March 16th (see chart below), but this did not prevent a major epidemic from burgeoning in the country’s spring. Note that the policy was put in place 199 days before the peak of daily deaths, which would be the equivalent of the U.K. having closed its borders on September 27th 2019.

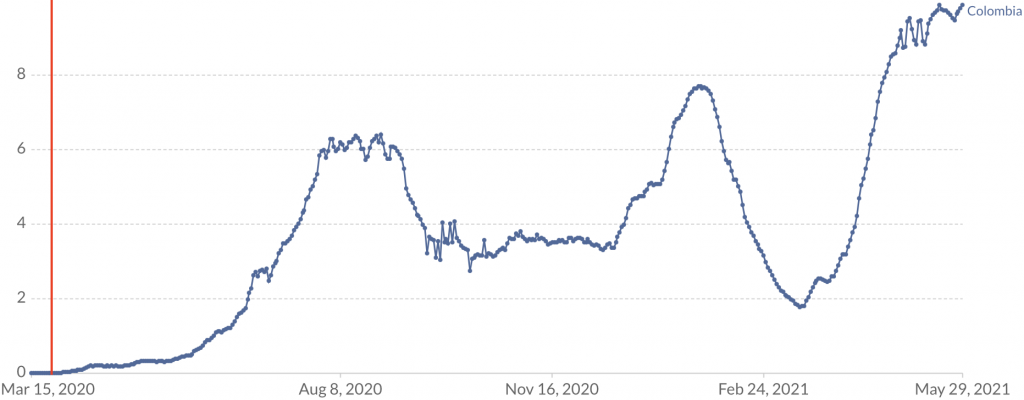

Colombia imposed a total border closure on March 25th (see chart below), but this did not prevent a major epidemic from burgeoning in the country’s spring. Note that the policy was put in place 131 days before the peak of daily deaths, which would be the equivalent of the U.K. having closed its borders on December 4th 2019.

Although several East Asian countries have apparently used border controls to great effect, it’s unclear whether the U.K. would have been able to replicate their success. In a recent article, the Economist suggested that people in East Asia may “benefit from ‘cross-immunities’ – a level of protection against SARS-CoV-2 conferred by past infection by other viruses circulating in the region”.

Assuming Britain wouldn’t have been able to contain the virus, deciding whether to impose border controls then becomes a trade-off between the benefits of buying time versus the risks of postponing the epidemic until the winter. I’m not sure what the correct answer is here, but given the risks of postponement, Cummings is wrong to suggest that imposing border controls was “obviously” the right thing to do.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

You either do China, or you do Sweden.

Faffing around in the middle does nobody any good.

Dom is a fan of the Chinese approach, which is what they have adopted in Aus and NZ and the downsides of that are now apparent – rational vaccine hesitancy. So now they have no out until the vaccines improve drastically in efficacy and safety.

We know the ‘hard shell’ approach is problematic. That’s been the EU trade policy for decades.

I cannot see how any border measures would have prevented C19 from entering the UK once it arrived in Europe.

Lorry drivers are in and out continuously, as are migrants. Recall in the early days that there were very few tests available, I can remember the first person I knew who had a test – it was unusual- and I don’t think I knew of anyone else being tested for at least a month or two.

It (in whatever form it really exists) was already here in November/December. If not that half my office had a really nasty a n other respiratory virus that suddenly disappeared in Jan…

Agree. Our family all had it in December 2019. Friends in November 2019. Our doctor called it the Adino variant of the annual flu and it would take around six weeks to run its course. We were due a bad flu year as the previous 6yrs were actually very low.

we have been scammed. In no other flu year was the economy shut down, people imprisoned, tests, hysterical language etc employed. We used our initiative and acted responsibly. It seems to me that psychological programming is being used on nations in order to inject something lethal into their systems. Whoever heard of a flu jab being mandatory or indeed injecting anyone under 70yrs old. Whoever in recent history saw hundreds of perfectly healthy young people queuing up to be jabbed on a beautiful summer day when they should have been enjoying BBQs, beach and countryside air. We have been indoctrinated to be fearful.

Australia, New Zealand and Taiwan all had the advantage of not having any lorry-borne international trade to worry about.

In the cases of Australia and NZ it is because their sheer remoteness (the Tasman Sea is over 1000 miles wide, while the English Channel is more like 25 miles wide) means that the wasted labour costs from having a lorry driver babysit the cargo across the sea would massively outweigh the time savings that roll-on roll-off would enable, while in the case of Taiwan it is because it is in a state of war with its corresponding “mainland”.

Yes – but they don’t want an ‘out’!

I wonder how many Aussies and Kiwis support zero Covid not so much because they fear the virus, as because it is a great excuse to ban immigration?

Hahahaha… air circulating stops at the far side of the channel!

If you want to play God and go for suppression and eradication, yes, you need to close the borders, but early, before the virus could take hold meaningfully.

But that’s useless if the virus has already spread much and you also need to keep them closed for good, if you can’t get hold of a 100% sterile immunity providing vaccine- see NZ&co.

It’s just ivory tower epidimiology what Cummings, Sridhar&co. are proposing and following.

“and you also need to keep them closed for good“

The bleedin’ obvious hard truth (to anyone with a brain).

(What does that say about genius Cummings’s brain?)

I’m sure he’s not stupid in the classical sense, but his personality, emotions and character flaws seem to get in the way of an honest, objective exercise of his intellect to understand issues and think about solutions. The same goes for many others like him who have their hands on or near the levers of power, here and elsewhere.

Sadly there’s an assumption that so many “intelligent” people couldn’t possibly be wrong about something, which assumes their intelligence is not blinded by human weaknesses.

More of the same crap. It was here months before they started to panic. Unless you’re going to live in a bubble (how’s that working out for you NZ?) you’re not going to stop a virus getting into the country and maybe even not then.

It’s working out even worse for Australia.

More of the same crap. It was here months before they started to panic.

Exactly.

How anyone can argue that border controls in the UK would have achieved anything, other than trash the economy and piss everyone off, is simply beyond me.

Sure. They should have closed flights to and from China while they had a live massive outbreak though – even if only to make a point.

This all assumes the virus wasn’t already here in flipping January 20, which is a huge assumption considering Paris has admitted blood samples taken during hospital operations in November show the virus and it has been detected in sewage samples taken in Barcelona in Spring 19.

If it was in Spain by Summer 19,are we rely saying not one of the millions of holidaying Brits had taken it back?

As there was no way of testing the 10,000 plus lorry drivers arriving weekly this idea of a hard border closure is nonsense on stilts especially as the virus was probably endemic by December 19.

“MADRID (Reuters) – Spanish virologists have found traces of the novel coronavirus in a sample of Barcelona waste water collected in March 2019, nine months before the COVID-19 disease was identified in China, the University of Barcelona said on Friday.”

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-spain-science-idUSKBN23X2HQ

It assumes there really has been a deadly virus rampaging across the globe for over a year.

Leave the borders and a few people get covvie.

Close the borders and everybody starves. This overpopulated country cannot feed itself.

And many small companies go out of business – even quicker than they have already (or nearly) done so.

Small companies are not sacrosanct. Going bust due to shocks is part of business. That’s why you have business interruption insurance.

Destroying the small businesses themselves and the livelihoods they support, whilst not sacrosanct per se certainly is, foolush, cruel, unnecessary, unhelpful, countersensual, destructive in micro andmacro ways.

Natural shocks, yes. Not those deliberately engineered by idiot, evil governments.

It’s utterly perverse to say that insurance is the solution to the cost of lockdowns, only slightly less perverse than to say that insurance is the solution to the cost of BLM rioting.

It’s meant to cover exceptional/unanticipated events, not year-long assaults on liberty and property rights.

Most business interruption insurances do not cover pandemics and those that’s do are still refusing to pay out.

Businesses do not wantonly destroy themselves to get insurance. Going bust is the very last thing businesses want to do. SMEs are usually entrepreneurs who want control of their destiny.

You can move food in and out in a secure manner – as they are doing in Aus and NZ.

Man cannot live by bread alone

Anyone got a brain to spare?

Because they were already set up to trade that way: they are so far from other countries that trading by truck using roll-on roll-off ferries would make no economic sense even if there was no such thing as Covid.

Singapore (which imports all its food IIRC) managed to close its borders, but I suspect using Covid-safe means (container ships and aircraft) to import food for a city of 5.7 million is more practical than doing it for a country of 66 million that wasn’t set up in the first place to do all its trade that way.

Singapore hasn’t managed to keep Covid out either.

UK hasn’t been self sufficient in food since around 1840.

We could only be self sufficient if we are prepared to cut down all the trees and subsist on a diet of turnips, kale and potatoes.

We are a trading nation cos we have to be.

The nasty shock that was World War II’s Battle of the Atlantic spurred Britain to improve its agricultural productivity, and in the last century we came closest to food self-sufficiency in 1984 (source: David Edgerton’s The Rise and Fall of the British Nation).

I wonder why we became more import-dependent again after 1984? Was it that British consumers became more discerning in their tastes (the postwar British diet was the butt of jokes internationally) or was it just down to increasing population?

We got prosperous and wanted luxuries which don’t grow here, oranges, olive oil, lemongrass, or grow more expensively here, tomatoes, grapes etc.

We’ll be back on potatoes soon.

No one, even Dom, suggests stopping food imports.

LS has given far too much credence to the official narrative over the last month or so. There has been no pandemic and this authoritarian rule has got nothing to do with a virus.

I said the same words over a year ago and I’ll keep saying them.

Forced measures simply delay the inevitable. It could be argued that if they han’t shut down when the infections were decreasing and had let it run its natural course, then therewould have been no second wave, other than the normal winter increase in respiratory problems.

I anticipate, with a sense of foreboding, the undoing of the antipodean restrictions.

The second wave in Europe was driven by seasonality, so it would likely have happened regardless of policy (at least given the very justifiable assumption that Zero Covid was impossible for European countries), as demonstrated by Sweden.

Not really a “second wave” if it’s seasonal, is it? What “wave” of flu are we on now?

Yep it’s working so wonderfully well there isn’t it? Life in a gulag with no end in sight.

Why did no prior strategy recommend border controls?

Why (like all the other main MPIs) were border controls not employed in the many worse epidemics?

Why would you touch any recommendation from Cummings other than with a barge pole?

The UK is not NZ – and you can see the problems they’ve now got!

Viruses don’t know borders. They always mutate to survive. Stop giving them names it’s just part of the nonsensical fear mongering. We should call this out for what it is and take back our lives by ignoring the strictures and laws most of which are unenforceable.

Sure. Close the borders, but then you are like Jan van Dyke trying to plug the leaks with your fingers. Sooner or later…………

S Korea: hailed as a success story until August

Taiwan: hailed as a success story until the breach two eeks ago.

Vietnam: hailed as a success story until the breach a couple of weeks ago.

If a country in isolation is to date successful, it is constantly on countdown to the next isolation failure and potential breach:

Like:

60 Days since the last breach! YAY! We Are Great!!

Dumb asses, you are just that much closer to the next.

South Africa closed its borders on 26 March. Fat lot of good it did.

And a curfew.

And compulsory masks outside.

And banned sales of alcohol and cigarettes.

Trashed the economy.

Fat lot of good.

https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/south-africa/

Not just South Africa: didn’t pretty much all Spanish-speaking countries lock down brutally but to no avail?

Was Spanish-speaking South America a victim of mass infection from Brazil, or was it a case of their leaders failing to recognize that what worked in the Asia/Pacific region wouldn’t work there (such that it was in fact Bolsonaro who made the right call in that continent)?

This is overlooking three points: 1. Populations in Oceania and much of Asia have greater t-cell memory immunity (as shown by a recent Japanese paper), based on more circulating corona viruses over many years – and so we do not know the true presence of COVID in say Australia or NZ, 2. We do not know fir sure how long C19 has been in the UK but some theories and poo studies propose a longer than even dec 2019. 3. New Zealand is still locked up to much trade and tourism and increasing evidence of increasing poverty among Pacific Islanders and within NZ itself… all glossed over by the mouthy and to me obnoxious PM.

We are now being to.d little by little that COVID is just annual flu with a different name. That it is not deadlier than any other coronavirus. Many of us knew this from the beginning because we asked questions and looked around us.

Those who set an hysteria in motion were Government advisers and modellers (mainly funded by big pharma) and the media (owned by the globalist cartel which includes big pharma). Trump was Orange Man Bad when he exposed the truth. Boris was a disgrace for not supporting a fellow Democratic leader but listening to the Clinton/Obama faction.

We are now slowly being fed the real truth. Gain of Function being funded by Fauci and the Democrat Party (Globalist owned) in conjunction with CCP, WHO and parts of the Civil Service in UK. Trump and Brexit interfered with the programme so a yearly flu outbreak was hijacked to bring the programme forward. I could go into detail, but those who are intelligent enough to have been joining the dots know where all this heading.

it is a great pity that Boris felt it necessary to show his Lord Halifax credentials whilst President Trump followed the Churchillian route. The public will eventually know the truth. Should it really be true that nearly half the population are now injected with a gene therapy then we will have a REAL crisis on our hands over the next few years. God forbid that the present incumbents of Westminster are still in power.

Let’s for one moment be ridiculously generous to the “If Only We Had Closed The Borders Early Enough” argument. Let’s assume the borders were closed sufficiently early (Jan ’20? Dec ‘ 19? Nov? July?) to buy some time.

Time to do what? To work out who was genuinely vulnerable and ways of affording them genuine protection. With a fraction of the money thrown at this thing, care homes could have been five star accommodation with live-in staff. We could have all been offered screening for the metabolic health problems that made some relatively young people vulnerable (insulin & leptin resistance, vitamin D deficiency) and advice on how we might reduce those risks if we so wish. Or we could have just thrown a bit more PPE at the problem and made an early start on the insanity: treating children like bioweapons, wrecking their education, wrecking our economic & cultural life, assaulting free speech etc.

Either way, buying time in such a way is allowing ourselves the benefit of hindsight. You’d have to go back in time to put in place whatever measures you favour. This is a temporal, rather than a geographical question.

What a load of shite!! There was no need for any measures to be taken. If we had continued on as we were in 2019 with no lockdowns, social distancing or any of that crap nothing would have happened. In fact we would have been way better off than we are now! The whole thing was a scam from start to finish, we’ve been played and we’re still being played!

Given that 3 of 5 in my family had it starting 29th Nov ‘19 ( donated convalescent plasma a few months later confirms this) then it would have been pointless to close the borders in 2020 as it was already here!