“If The New COVID-19 Strain is More Transmissible, Why Isn’t It Taking Over in Every Region?”

Joshua Loftus, Assistant Professor of Statistics at New York University (and definitely not a lockdown sceptic), poses this question in the Spectator.

Let’s look at these estimates of the percent of the UK population testing positive, broken down based on whether the test result “is consistent with” the new strain or otherwise. We can download data with estimates of COVID-19 infection rates from the Office of National Statistics. First let’s see the rates in two regions, the one where the new strain grew most rapidly and another region where it hasn’t.

Next, here are all the regions sorted (top left to bottom right) in the order of the maximum estimated prevalence of the new strain.

If the new strain has a biological advantage that makes it more transmissible why isn’t it taking over in every region?

Loftus stresses this is not a rhetorical question. However it is a real question that needs answering, and one that’s also being asked by Professor Francois Balloux on Twitter:

A number of media outlets have reported on the new technical briefing from Public Health England that shows considerably more being infected by carriers of the new variant than carriers of other variants. Here’s the report in the Times.

Contacts of people with the new coronavirus variant are 54% more likely to develop the disease, according to new analysis from Public Health England.

They found, however, that it did not appear likely to cause more severe disease or higher death rates.

Researchers found the “secondary attack rate”, or proportion of contacts of confirmed cases that develop the disease themselves, was 15.1% for people with a confirmed case of the new variant and 9.8% for people confirmed to have another variant.

The figures were published yesterday in a technical report on the variant, now named VOC (variant of concern) 202012/01.

Ministers pointed to the variant’s increased infectiousness when announcing higher Tier 4 restrictions for much of England earlier this month.

However, the PHE briefing does not draw any conclusions about transmissibility from the data it presents (it doesn’t mention transmissibility at all). Is this because the authors are aware that this may be just coincidence? In other words, that it appears to be more transmissible just because most of the infections with it happen to be in the areas that are currently surging? This by itself would explain why the secondary attack rate (the proportion of contacts who become infected) for the new variant in England is higher in recent weeks – because it happens to be the variant most prevalent in the areas of the country where more people are currently being infected. To know whether it is the new variant itself that is responsible for the higher secondary attack rate, or something else, we would need to see it higher in other regions, not just the one currently surging. And as Loftus and Prof Balloux observe, there is not currently evidence of that.

Stop Press: Nic Lewis has done a thorough analysis of the claims of greater transmissibility for the new variant and shown that despite the growing panic evidence is so far lacking.

Fact Check Fail

“Full Fact” is one of those over-confident websites that claims, unlike all those other websites which peddle mere opinion, to be supplying readers with the pure, unfiltered Facts. It has now brought the weight of its authoritative wisdom to bear on lockdown sceptics, with one Leo Benedictus penning a “fact check” entitled “Can we believe the lockdown sceptics?“. The London Economic claims this piece “definitively discredits lockdown sceptics“.

Unusually, it actually makes some effort to be kind to sceptics and says “we must not dismiss the lockdown sceptics’ claims out of hand… Mr Hitchens, Mr Cummins and Dr Yeadon all say that we should base our views on evidence, and on that we agree with them. However, on the overwhelming balance of the evidence, their claims are wrong”.

Benedictus claims there is much published evidence lockdowns work.

A research paper published in June in Nature, one of the most prestigious scientific journals in the world, concludes: “Our results show that major non-pharmaceutical interventions – and lockdowns in particular – have had a large effect on reducing transmission.”

Another in Science in July said: “Focusing on COVID-19 spread in Germany, we detected change points in the effective growth rate that correlate well with the times of publicly announced interventions.”

Another in the BMJ said: “Earlier implementation of lockdown was associated with a larger reduction in the incidence of COVID-19.”

Mr Cummins may have been referring to a research paper in one of the Lancet’s online journals in July, which said that “full lockdowns… were not associated with COVID-19 mortality per million people”. But so much research is published, especially on Covid, that it is often possible to find at least some evidence in support of almost any view.

For instance, he might instead have referred to a different paper in the same journal eight days earlier, which said: “With a tighter lockdown, mobility decreased enough to bring down transmission promptly below the level needed to sustain the epidemic.”

Some science supports Mr Cummins on some points, in other words, but a great deal – which he does not mention – contradicts him.

Let’s take a closer look at these.

The June Nature paper is by Flaxman et al and is a model-based paper by the same team from Imperial College whose modelling inspired the lockdowns in the first place, so they are not exactly an impartial team. The June paper is notorious for making many dubious assumptions, as documented here by Nicholas Lewis. In fact, so troubling is the paper that last week Nature itself published a “matters arising” paper by Soltesz et al pointing out many of its flaws. It says:

We conclude that the model is in effect too flexible, and therefore allows the data to be explained in various ways. This has led the authors to go beyond the data in reporting that particular interventions are especially effective. This kind of error – mistaking assumptions for conclusions – is easy to make, and not especially easy to catch, in Bayesian analysis.

You can read our own critique of the Flaxman paper here.

The July Science paper, by Dehning et al , focuses only on one country, Germany, so cannot be used to counter international comparison data. In addition, Germany had an atypical spring as it did not experience any excess deaths.

The July BMJ paper is by Islam et al and is also model-based. It suffers from only using “case” data (which is unreliable as it depends on who is being tested and how many tests are being carried out) and does not look at deaths. To measure lockdown strictness it relies on the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker rather than using mobility data, and only considers five broad types of intervention rather than any finer measure of severity. This means it counts Sweden as implementing as many restrictions as many of the other countries because it did something in four out of five categories, despite Sweden’s restrictions being much lighter than others. Then the results are not actually very favourable to lockdowns at all. They show huge variation between countries, with all those with fewer restrictions seeing a reduction in cases over the period at a rate greater than many of those with more restrictions. Overall the study finds restrictions reducing “cases” by just 13% on average, a paltry impact for the immense cost.

On the other hand, the July Lancet paper by Chaudhry et al that Benedictus dismisses as an example of it being “often possible to find at least some evidence in support of almost any view” is in fact the main peer-reviewed article which carries out an international comparison of Covid mortality. It is notable that Benedictus doesn’t even attempt to counter the point that Covid mortality was not associated with lockdown strictness and timing, because he can’t. It is a fact, as Chaudhry et al show.

The Lancet paper by Vinceti et al that he then cites by way of riposte only looks at Italy and only at case numbers, not deaths. It concludes that one lockdown was ineffective while the second one worked, which it attributes to strictness. However, the context to keep in mind is that Italy had one of the worst Covid mortality rates in the world during the spring, and the later lockdown may have “worked” only because it coincided with the change of the season, a possibility the study does not consider. The conclusion that the first lockdown did not work supports the sceptics’ position.

The lack of consideration of “organic” alternatives as explanations for epidemic decline such as warmer weather and rising population immunity is a general failing of many of the coronavirus studies, made more obvious by the fact that the epidemics declined across all contexts regardless of how many or few restrictions were in place. In each region, the lifecycle of the epidemic followed a Gompertz curve.

To back-up his “fact check”, Benedictus claims that the epidemic in all regions in England declined at the same time, suggesting it was a result of lockdown. However, this is not actually true. As the Government dashboard shows, London deaths peaked around April 5th, North West deaths peaked around April 13th, and Yorkshire and Humber deaths peaked almost two weeks after London on April 18th; London’s decline was also steeper. The seasonal effect of course provides an alternative explanation as to why the epidemic declined across the country at around the same time during the warm April weather.

Benedictus makes the mistake of assuming that everyone who’s been infected will test positive for antibodies in order to “prove” the Covid Infection Fatality Rate is higher than many sceptics claim. However, numerous studies have shown that not all people who are infected develop or retain antibodies. For instance, a large Spanish study found that less than 20% of symptomatic cases later had (IgG) antibodies, and a large Italian study similarly found only 25% of symptomatic cases later had (IgG) antibodies. (See here for more on this.) The role of T-cells and pre-existing immunity in the immune response has also been shown by a number of studies. (See this in the BMJ and this pre-print.)

Benedictus says it is “hard to see how banning human contact could fail to reduce the spread”, not recognising that lots of contact isn’t banned – many workplaces continue, supermarkets and other shops remain open, often schools are open, and there are hospitals and care homes. Furthermore, confining people to homes can increase spread within homes.

Benedictus disputes Peter Hitchens’s claim that it was “not possible” for the lockdown announced on March 23rd to have caused the subsequent decline in daily infections and deaths, saying it is not “generally accepted”. But Chief Medical Officer Chris Whitty himself stated to MPs in July that new infections were falling before lockdown. Oxford’s Professor Carl Heneghan has pointed out that GP data shows suspected Covid referrals dropped off before lockdown. The standard estimate for the average lag between infection and death is 23-26 days, which is the figure used for example by the Imperial College team in Flaxman et al, which puts peak infection around March 15th, 23 days prior to peak deaths on April 8th and nine days before the lockdown came into effect. London death peak was three days earlier, putting its infection peak on March 12th.

Benedictus claims that the second waves in the autumn disprove sceptics’ claims about herd immunity. However, it’s worth bearing in mind that some of the worst “second waves” have been in countries not badly affected in spring, such as Switzerland, Germany, Slovenia and Czechia.

It’s true that the UK did experience excess mortality in November and December, but only peaking around 20% and declining during December. Other causes of death are running below average, suggesting there is some misattribution going on; the other obvious cause of extra deaths this year is lockdown. It’s not true to say that lockdown sceptics necessarily expected an easy ride for hospitals in the autumn, with many anticipating further Covid deaths during the colder months, particularly in areas not strongly affected in spring. The point about there being no second wave is that this autumn/winter Covid epidemic is much more like an ordinary seasonal viral epidemic than something similar to the spring when the disease was new, and this time round infections seem to be caused by local outbreaks rather than a national tsunami. The point about false positives and pseudo-epidemics is not that there is no Covid around anymore but that problems with the testing regime turn something eminently manageable and basically normal into a crisis that appears much bigger and more disastrous than it really is.

Benedictus claims that lifting the lockdowns explains the resurgence of the virus, but this is untrue as lockdowns were lifted much earlier in the year yet there was no new surge until the autumn. The resurgences, insofar as they are real and not an artefact of increased testing, are much better explained by the onset of colder weather.

A more general criticism of the “fact check” is that it fails to look at the countries and states like Sweden, Belarus, Tanzania, North and South Dakota and others in the autumn such as Switzerland and Spain which did not impose strong restrictions but did not experience higher rates of Covid mortality than those that did. This means it neglects to consider the key question: what would happen without lockdown? Benedictus claims “we will never know the effects of things we did not try”, but of course we can look at other places that didn’t lock down. He quotes a Government report claiming lockdowns saved thousands of lives by preventing hospitals being overwhelmed, but fails to spot that hospitals were not overwhelmed in those regions that forewent lockdowns. Worth remembering that hospital services in the UK and other countries are routinely stretched in the winter, with people often being treated on trolleys in corridors.

In sum, Leo Benedictus’s attempt to “fact check” the lockdown sceptics falls short. He fails to engage our most important points about the countries which show epidemics declining without interventions, dismisses the significance of the main international study comparing different rates of Covid mortality, and makes factually dubious claims himself, such as that the epidemic in England began to decline in all regions simultaneously.

Must try harder.

Five Reasons Not to Close Schools

There follows a guest post by Toby Young.

Can we expect an announcement later today about whether the Government is intending to close schools? Health Secretary Matt Hancock is due to deliver the news about which other areas in England are being placed in Tier 4 after the Brexit vote and today is a good day to bury bad news, given that the headlines will be dominated by Brexit. Michael Gove said on Monday that the Government’s intention was to reopen primaries next week and make sure children in Years 11 and 13 returned, but was non-committal about other year groups. The Telegraph seems to think the announcement will be today and will include, among other things, a one-week delay in the return for Years 11 and 13.

In any event, just in case a decision hasn’t yet been made I thought I’d briefly remind the Government why closing schools is a bad idea.

1. Closing schools is regressive in that children from disadvantaged backgrounds pay a higher price than their peers. As Brendan O’Neill pointed out in the Spectator yesterday, this fact seems to have been forgotten by all those well-educated, comfortably-off “experts” recommending the closure of schools in the media this week: “There have been many shocking sights in this cursed year. For me, one of the most shocking has been the sight of comfortably off, Oxbridge-educated experts and journalists agitating for the closure of schools even though they know this will hit poor kids hardest.” He then cites the overwhelming evidence that it’s the poorest children that suffer the most from school closures.

Research by University College London, published in June, following the closure of schools during the first lockdown, found that 71% of state-school pupils had between none and one online lessons a day, while many private schools were providing four or more online lessons a day.

The National Foundation for Educational Research found that 42% of state-school children were not completing their work, and that “pupils in the most disadvantaged schools were the least likely to be engaged with remote learning”.

There were big divides even among comprehensively educated students. The Sutton Trust found that kids in middle-class homes were twice as likely to take part in online lessons as kids in working-class homes. Forty-four per cent of middle-class children had spent four hours or more on schoolwork each day when schools were closed, compared with just 33% of working-class children.

It isn’t hard to see why. The less well-off a child’s family is, the less likely that child is to have a computer, a quiet room to learn in, parents who have the time to assist with learning. When you push education out of the classroom and into the home, it is inevitable that social inequality will rear its ugly head.

And, of course, school closures result in ‘learning loss’ for all children, not just the disadvantaged. From a BBC News report in September:

The National Foundation for Educational Research’s survey questioned a weighted sample of almost 3,000 heads and teachers in about 2,200 primary and secondary schools across England.

The research was carried out just before the end of term in July – and showed how much children had fallen behind by the end of the last school year.

Almost all the teachers questioned (98%) said their pupils were behind the place in the curriculum they would normally expect for the time of year.

Overall, teachers said they had covered just 66% of their usual curriculum by July, putting pupils three months behind in their learning.

2. Paediatricians believe the harm caused by school closures outweighs the harm supposedly prevented by closing them. Dr Danielle Dooley, a Medical Director at the Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C., told NPR in October: “As a paediatrician, I am really seeing the negative impacts of these school closures on children. Going to school is really vital for children. They get their meals in school, their physical activity, their health care, their education, of course.” A survey published by NHS Digital in October found that one in six children aged five to 16 were likely to have a mental disorder, thanks, in part, to the impact of the first lockdown.

3. The evidence that closing schools reduces virus transmission is threadbare, at best. Research carried out by the World Health Organisation and the Royal College of Paediatricians didn’t turn up a single case of a child under 10 transmitting the virus. Last May, 22 EU member states reopened schools and found no evidence that it posed an increased risk to pupils, teachers or families. Indeed, the Prime Minister of Norway appeared on television to apologise for over-reacting to the crisis and said she regretted closing schools.

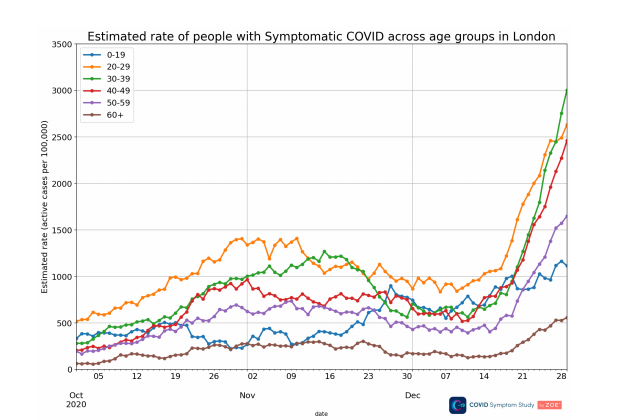

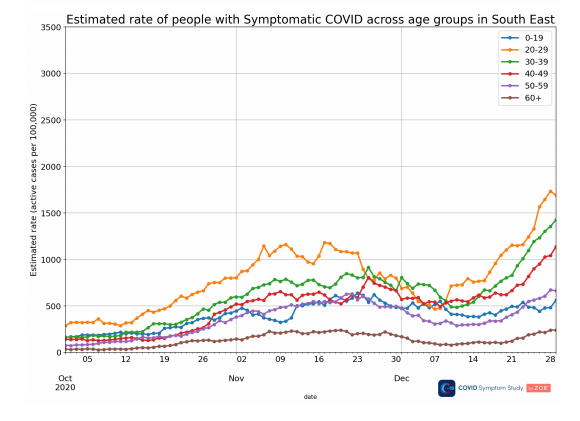

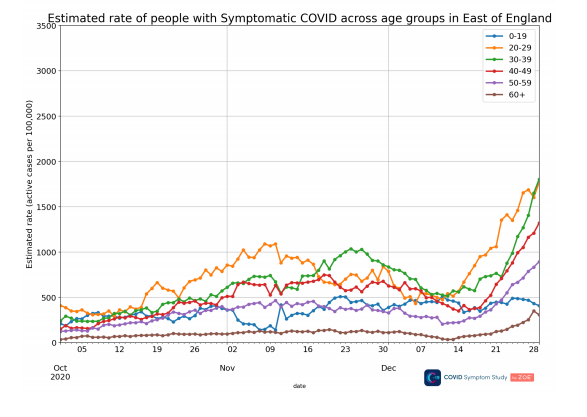

4. A large part of the rationale for closing schools again, in spite of the harm caused by closing them in the first lockdown, is that children are more susceptible to the new variant – including primary school children. But there’s little empirical evidence to support this claim. On the contrary, if we look at the ZOE app data showing symptomatic cases in the three regions said to be worst affected by the new variant – London, the South East and the East of England – infections appear to be relatively flat among those aged 0 – 19.

5. We’re often told by the teaching unions that teachers don’t want schools to reopen, but the data suggests otherwise. A Teacher Tap survey of 6,000 teachers in November found that just 39% of teachers thought schools should close during the November lockdown, while 46% believed they should remain open. Among headteachers, 69% were in favour of keeping schools open.

If the NHS is so Overwhelmed, Why is it Dismantling the Nightingales?

There follows a guest post by regular Lockdown Sceptics contributor David Livermore, Professor in Medical Microbiology at the Norwich Medical School.

I read, fascinated, that the Government is dismantling Nightingale Hospitals.

This is despite rising cases, admissions and, above all, SAGE’s assertions about the hazard posed by the increased transmissibility of the VUI202012/01 variant. Support for the view that the variant really is more transmissible came yesterday from PHE’s finding that it infected 15% of a case’s contacts, as against 9.8% for the classical virus.

We know that, even without VUI202012/01, around 10-20% of reported hospital ‘cases’ with COVID-19 caught it there, whether consequentially or not. Some hospitals have seen much larger outbreaks. The NHS adds these ‘nosocomial’ cases to daily totals as ‘admissions’ even though the patients weren’t admitted with COVID-19.

If this variant is able to spread 50-70% more efficiently, you’d expect it do so in hospitals, even with the best of infection control efforts by front-line staff. Add increased transmissibility to rising Covid admissions and general winter pressures and you’d expect a sharp increase in hospital-acquired SARS-CoV-2 infection.

I posed the question of whether this was happening in the Daily Mail a week ago along with the now-answered one about household contacts.

Since which answer came there none. Perhaps it has been delayed by Christmas?

Except that, if the Government is dismantling the surge capacity provided by the Nightingales, one can only conclude that they are nothing like as worried about the mutant’s alleged transmissibility as they’ve made out.

This point applies all the more strongly in view of the fact that the NHS has apparently cut many beds in its own hospitals to aid social distancing and to reduce nosocomial transmission. This point, not widely flagged, is made in Sarah Newey’s Telegraph article of December 21st. She quotes Dr Adrian Boyle, Vice President of the Royal College for Emergency Medicine, as saying that the numbers of beds per bay have been cut from six to four, and estimates a total loss of 10,000 beds.

The notion that dismantling the Nightingales is just a staffing issue doesn’t really hold water. In the face of a strain that really is more transmissible you’d want – even more strongly – to ‘cohort’ infected patients on separate sites so far as possible, along with dedicated staff to look after them. This is the principle of classical fever hospitals, and should be practicable if there are fewer beds available at NHS sites. Preferably, you’d choose staff with a history of COVID infection and some anticipated immunity. The aim would be thereby to protect non-Covid patients, and staff, at the main NHS sites.

Since this isn’t being done, one can only conclude either that the Government isn’t really so worried about VUI202012/01, that it’s hopelessly confused, or that the cabal of modellers and behaviourists who dominate SAGE don’t have a grasp of basic hospital infection control.

Why Winter is Not Spring

There follows a guest post by the senior doctor – ex-NHS – who writes regularly for Lockdown Sceptics.

Yesterday we are told that hospitals are treating more Covid patients than at the “peak of the spring”. Professor Andrew Hayward, an official adviser to the Government and a member of NERVTAG, has helpfully shared his advice with the general public that a “national catastrophe” will soon be upon us unless more stringent population control measures are enacted indefinitely.

Toby kindly invited me to analyse the available data and assess to what extent these conclusions are justified. The usual caveats apply – one can only comment on what the NHS permits the public to see, and the granularity of the information, especially around the accuracy of diagnostic recording, is far from satisfactory.

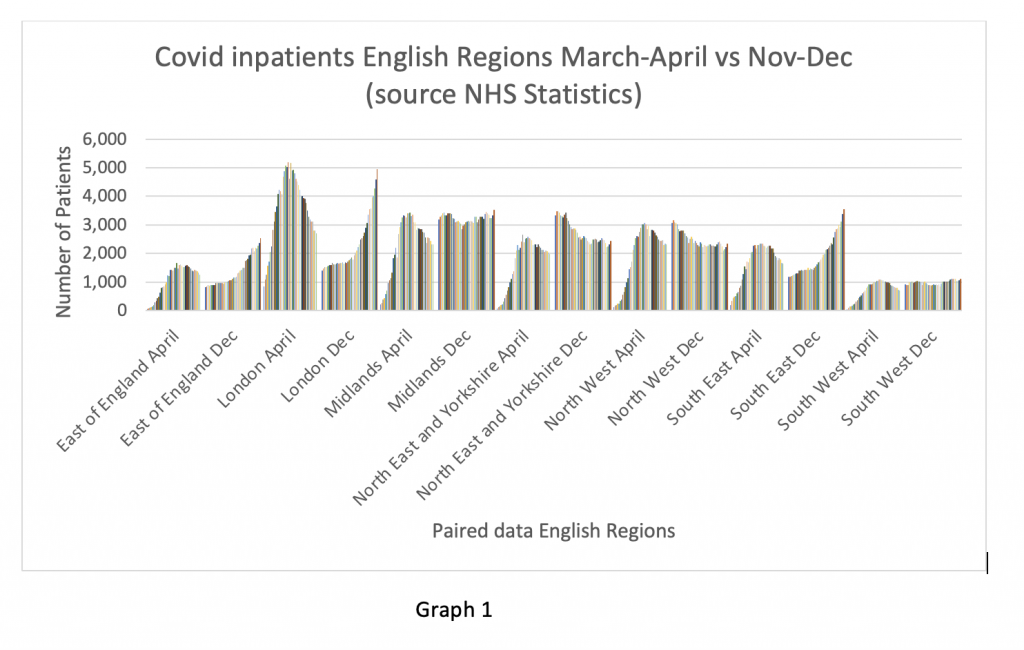

Firstly, a look at the headline figures for inpatients across English regions (Graph 1). I have expressed these figures as paired data comparing March – April with Nov – December 28th. There are clearly possible errors here in the sense that we know when the spring peak happened and we don’t yet know when the winter peak will occur, or if it has already in some areas. Further, the date selections are arbitrary choices based on the available data, so they may not be directly comparable time series. Nevertheless, observing trends is instructive and does allow us to comment on whether we are in a worse situation now.

The immediately obvious observation is that there has been a recent rapid rise in admissions, particularly in London and the South East. The South East and East of England are currently treating significantly more Covid inpatients than in the spring, while most other areas are on a par with the spring as of the end of December.

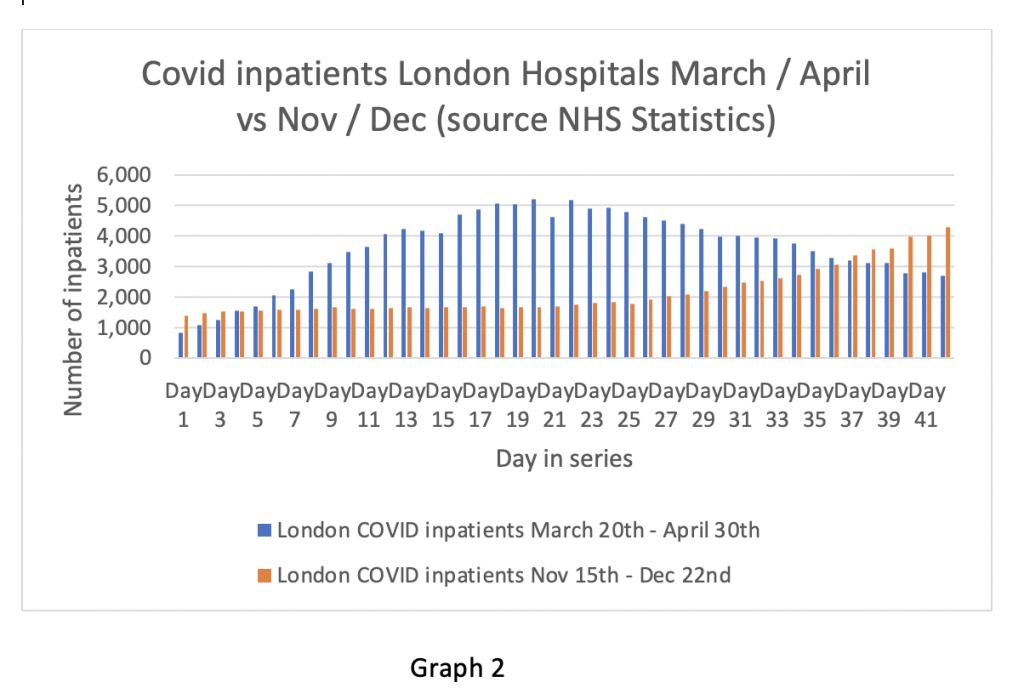

The London inpatient figures, which show the most dramatic rise in the last week, are shown in Graph 2. While on a rising trend, the spring peak has not been exceeded as of December 28th. It is still debatable what has caused the sudden acceleration in cases. Circumstantial evidence suggests that the new variant is spreading faster in London, the South East and the East of England than in other areas, but there is insufficient evidence as yet to show causation. A paper published today by NERVTAG contains interesting data suggesting that the “new strain” VOC 202012/01 may be more contagious than the previously established variant. Luckily, the data so far also suggest there is a lower hospitalisation rate with the new variant (0.9% vs 1.5%), but this difference did not achieve statistical significance in view of the limited sample size. We await further analysis with interest.

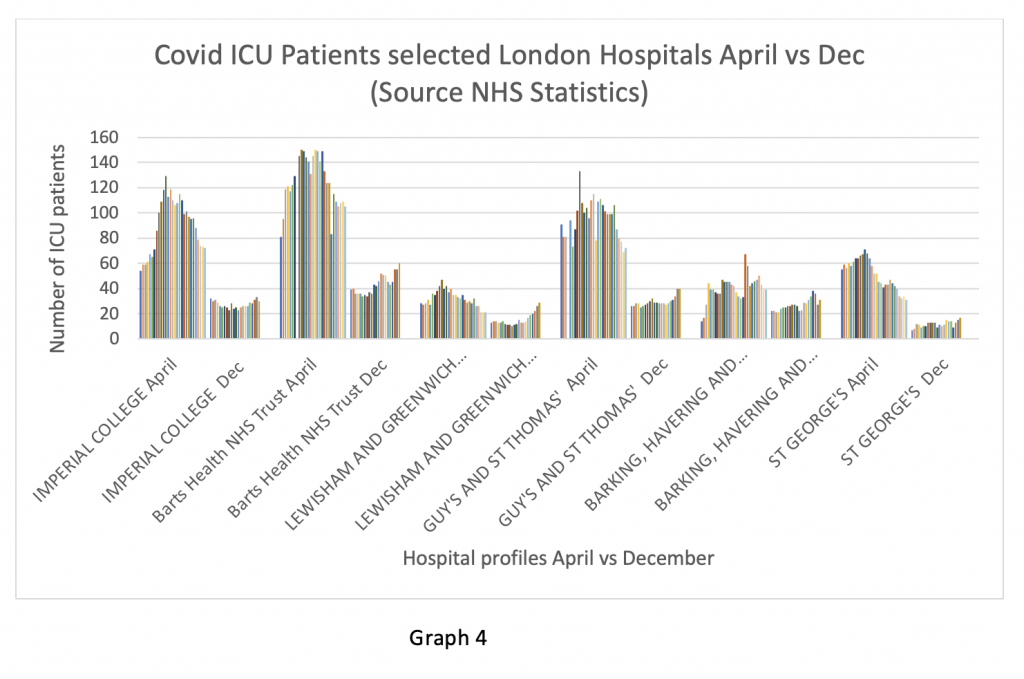

The London ICU figures show a marked reduction on the spring figures (Graph 3), with current Covid ICU bed occupancy about 50% of the spring peak. Notably, the total available number of ICU beds in the capital is also considerably higher than in the spring, so expressed as a percentage of currently available beds, Covid patients probably account for 30% of the total. Finally, the ratio of Covid inpatients to Covid ICU patients has also changed from the spring. In April, approximately 20% of patients admitted to hospital with acute Covid ended up in ICU. So far this winter, that percentage has fallen to around 13%. So, there may be more patients ending up in hospital, but it appears that either they are proportionately less sick than in the spring, or that the early use of high dose steroids and anticoagulants has a significant beneficial effect on disease progression. Discharge data is not available until the monthly summary on January 14th, which is a shame as this is a useful marker of overall disease stress. Comparison with the recent past suggests that ICU bed occupancy as of December 20th was lower than the average of the previous three years across all English regions and this does not take into account expanded surge capacity in 2020.

Looking at more detailed comparisons from individual hospitals in London, the difference between the spring and the winter so far is clear (Graph 4). Again, it must be borne in mind that we don’t know when the winter peak will arrive, so these are not direct comparisons and the data on Graph 4 only goes up to December 22nd. That said, it is obvious that with the exception of two District General Hospitals (Lewisham in the South East and Barking in the North East sector), London hospitals are nowhere near the spring peak – and these selected units are currently the most hard pressed in the capital. There is no question that things are difficult in some London hospitals right now and things may very well get more difficult before they improve. Nevertheless, the published figures do not support the assertion that the overall situation is as bad as the spring to date.

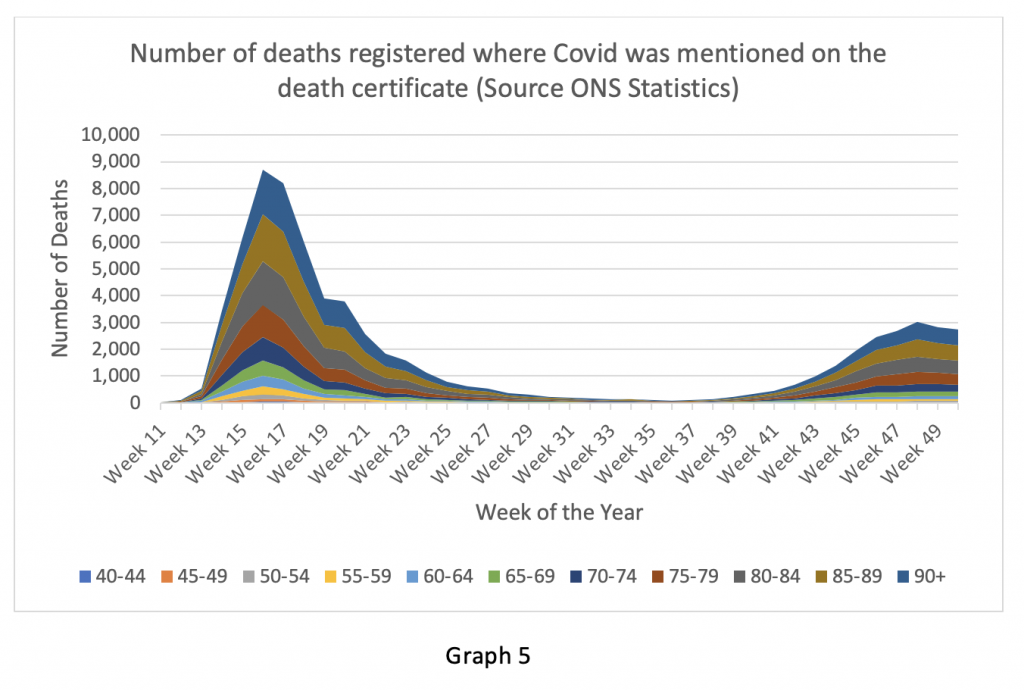

Graph 5 shows the ONS Death registration data for this year up to Week 50 (w/e December 11th) for deaths where Covid was mentioned on the death certificate. The difference between the spring and the winter is starkly apparent. Readers should bear in mind that there is a lag between the time of a death and its appearance in the statistics, so it is very possible that the numbers for weeks 51, 52 and the initial weeks of 2021 may yet rise, but it’s hard to see how the spring death peak of 2020 will be exceeded in the immediate future. I also observe that the Vallance/Whitty prediction of 4,000 deaths per day (28,000 per week), has not so far materialised.

I should also draw attention to the fact that Covid deaths in patients younger than 65 are too insignificant to be visible on the graph. The vast majority of Covid deaths are in the over-75 age group, and the vast majority of this section of the population have significant pre-existing comorbidities. Readers may wish to remember that the next time Hancock or Gove pronounce on the media that the virus is equally dangerous to all citizens – it clearly isn’t.

So, to what extent is the winter comparable to the spring?

The data above show that the total number of patients in hospital with Covid as the principle diagnosis is approaching the spring peak in some areas, but not all. The percentage of very sick patients needing ICU care is significantly lower than in the spring, so the overall burden of disease in terms of medical and nursing intensity is also lower. This situation may of course deteriorate in the coming weeks, but most hospitals are still managing to provide elective care despite the winter pressures, which is a good indicator that overall stress in the system is still substantially lower than in the spring. On the other hand, although the intensity of care per patient is lower, the organisational friction is substantially higher due to restrictions on cohorting of patients and moving patients around. This adds to the stress on staff who are already tired and demoralised by the constant demands of managers to hit ever more onerous targets.

Apart from the numerical differences visible in the above graphs, there are many organisational disparities between April and December. In the spring, the Covid pandemic hit a completely unprepared health system. Despite a ‘global pandemic’ being at the top of Public Health England’s risk register, there was no warning, no preparation, no effective testing system and no PPE for healthcare workers. Little was known about the disease or how best to treat it. High dose steroids, anti-coagulants and non-invasive ventilation were all unproven and used sporadically. It’s difficult to imagine a worse possible alignment of events such as happened in the spring. Despite that the system did not fail, nor was it ever overwhelmed. There was no “national catastrophe”.

The winter is significantly different to the spring. Most obviously, a winter surge cannot be regarded as a surprise. A casual review of newspaper headlines from any winter in the last 20 years will show the effect of seasonal respiratory disorders on the NHS – a ‘winter beds crisis’ is as much a traditional annual fixture as Christmas Day itself.

So quite clearly, a winter resurgence has been a known risk since May. Many preparations have been made – adequate PPE is available. We have many more ventilators, monitors and CPAP capacity than we did earlier in the year. However, the critical capacity gap in the spring was not equipment – it was suitably trained and experienced staff.

There have been six months to train extra ICU nurses to treat a known disease process. Six months to upskill already trained staff to enhance their capabilities and confidence. Six months to plan redeployment of staff from other duties to Covid wards. Six months to run tabletop exercises, to practice organisational and logistics drills, to stress test contingency plans in the event of predictable problems such as rising staff sickness rates. Six months to expand overall surge capacity. Six months to plan rest and support for our most exposed people, so they are psychologically ready for the winter upsurge.

Surely, our NHS cannot be as poorly prepared for winter Covid as it was in the spring? Surely, with six months to prepare, our experienced NHS managers must be confident in their ability to cope with a predictable risk without the system being ‘overwhelmed’?

Surely, after six months of preparation, the British public has a right to expect that our healthcare system should be in a position to manage winter pressures without constant advocacy of intensified national lockdowns and catastrophic shroud waving in the press from senior Government advisers.

Or maybe not.

Round-up

- “What Tier 5 restrictions could include, and who it might affect” – The Telegraph speculates on what the next level of restrictions might entail

- “2020: The year we sold our liberties for a medical tyranny” – Rob Slane in the Conservative Woman on the birth of a new religion: Covidianity

- “More under 60s died on roads last year than those with no underlying conditions from coronavirus” – The Telegraph tries to put Covid in context

- “Why the Twitter pitchforks came for me over an NHS statistic” – Paul Embery in UnHerd on the death threats and other bile he has had to put up with for presenting a simple statistical fact not dissimilar to the one above

- “Vitamin D and Viral Special with Dr. David Grimes” – Latest edition of Ivor Cummins’s Fat Emperor podcast

- “Covid-19 in Scotland – what does the data really tell us?” – Christine Padgham in Think Scotland finds tell-tale incongruities and concludes Covid is not the cause of the current excess deaths

- “Wuhan Covid citizen journalist jailed for four years in China crackdown” – Guardian report on the appalling treatment of coronavirus dissent in the communist country. Back in November the Royal Society disgraced itself by calling for anti-vaxxers to be jailed and cited China as a role model when it comes to dealing with “disinformation”. Would the society like to clarify whether it approves of this four-year jail sentence?

- “Why the EU’s vaccine strategy is failing” – Ross Clark in the Spectator on Brussels’s woeful failings on securing sufficient vaccines for timely use

- “What really happened in Verbier?” – Abi Butcher in Where to Ski And Snowboard says don’t believe what you read in the newspapers: the Swiss authorities gave Brits the option to return home rather than quarantine

- “Not so fast, Japan experts say, as COVID-19 vaccines raise hopes“– Masayuki Miyasaka, Professor Emeritus of Immunology at Osaka University, tells the Japanese Parliament that “safety has not been guaranteed” for the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines and “we have to treat them with extreme caution”

- “New Zealand scientists critical of anti-lockdown letter in top medical journal” – One-sided report in the NZHerald about the nasty response to this article by the group of sceptical scientists known as Plan B. They even published a mean cartoon

- “Are schools really driving up coronavirus infections?” – There’s little evidence they do, says Rhys Blakely in the Times

- “All over-50s can get Covid vaccine by end of spring, NHS chief pledges” – But will they deliver? In the Times

- “The unstoppable spread of Tier Four restrictions” – Luke Perry in Bournbrook bemoans our new authoritarian existence

- “For the middle-aged, by the middle-aged: how the responses to COVID have ignored the preferences of those most affected” – Paul Dolan, Professor of Behavioural Science at the London School of Economics, writes on the university blog that the Government should have sought a consensus along “focused protection” lines

- “Woman to appear in court charged with Covid breach” – Report from Nottinghamshire police of a woman who appears to have been grassed up by a neighbour for being at a friend’s house late at night on December 23rd. Bah, humbug

- “Why I changed my mind on lockdown” – Rod Liddle talks to Brendan O’Neill on the latest spiked podcast about how he became a lockdown sceptic

Theme Tunes Suggested by Readers

Five today: “Eyes Without a Face” by Billy Idol, “Dear Lord and Father of Mankind, Forgive Our Foolish Ways” sung by The Choir of King’s College Cambridge, “Wake Me Up When It’s All Over” by Aay Zee, “Tyranny 20” by Kit Sebastian and “Let my People Go-Go” by The Rainmakers.

Love in the Time of Covid

We have created some Lockdown Sceptics Forums, including a dating forum called “Love in a Covid Climate” that has attracted a bit of attention. We have a team of moderators in place to remove spam and deal with the trolls, but sometimes it takes a little while so please bear with us. You have to register to use the Forums as well as post comments below the line, but that should just be a one-time thing. Any problems, email the Lockdown Sceptics webmaster Ian Rons here.

Sharing Stories

Some of you have asked how to link to particular stories on Lockdown Sceptics so you can share it. To do that, click on the headline of a particular story and a link symbol will appear on the right-hand side of the headline. Click on the link and the URL of your page will switch to the URL of that particular story. You can then copy that URL and either email it to your friends or post it on social media. Please do share the stories.

Social Media Accounts

You can follow Lockdown Sceptics on our social media accounts which are updated throughout the day. To follow us on Facebook, click here; to follow us on Twitter, click here; to follow us on Instagram, click here; to follow us on Parler, click here; and to follow us on MeWe, click here.

Woke Gobbledegook

We’ve decided to create a permanent slot down here for woke gobbledegook. Today, it’s the Taking the Initiative Party and their plans to socially ostracise all who fall foul of the PC thought police. Report from MailOnline.

A leader of a new political party inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement has called for a “race offenders’ register” that would see people barred from jobs based on having been accused of “micro-aggressions” in the workplace.

Sasha Johnson, the self-styled “Black Panther of Oxford”, came to prominence as an organiser of the BLM protests earlier this year, where she was seen addressing crowds while wearing camouflage trousers, a black beret and a stab-proof-style vest.

The 26 year-old, from the Taking the Initiative Party (TTIP) said the racial offenders list would be “similar” to the sex offenders’ register – which is used to bar paedophiles from professions like teaching.

Speaking exclusively to MailOnline, she also called for “Holocaust-style” reparations for black people on the basis that capitalism racially discriminates against them, and called for the “defunding” of Britain’s police forces.

The Oxford Brookes graduate also attacked ethnic minority politicians such as Labour MPs David Lammy and Diane Abbott, saying “as black people… they have been tokenistic”.

Ms Johnson, who is a TTIP executive committee member in charge of activism, said TTIP was “not just a party for black people” and would also represent the working class.

The party operates a system of “coalition leadership” so there is no one specific person in charge and different spokesmen sometimes air views that contradict the official party line.

Outlining the party’s manifesto in her first interview with a national publication, she called for a national register of alleged racists that would ban them from living near people from ethnic minorities.

This would include people guilty of “micro-aggressions”, which the Oxford Dictionary defines as “indirect, subtle, or unintentional discrimination against members of a marginalised group”.

“It’s similar to the sex offenders register,” she told MailOnline. “If you were to be racially abusive to someone, [the register] would question whether someone is fit enough to hold a particular job where their bias could influence another person’s life.

“A lot of racism happens at work and places of education in a micro-aggressive way. If you exhibit an element of bias at work, you should probably receive a warning first [before later being added to the register] so people know in future that you hold these views.”

Ms Johnson said inclusion on the list would mean you could be excluded from “certain fields” of employment – or even banned from living near people from ethnic minorities.

“If you live in a majority-coloured neighbourhood you shouldn’t reside there because you’re a risk to those people – just like if a sex offender lived next to a school he would be a risk to those children,” she said.

Ms Johnson acknowledged that the idea came as a contribution from Black Lives Matter, and it was presented to TTIP at a party conference where BLM representatives were present.

While the party does not provide a list of specific offences which would warrant inclusion on the register, its manifesto does state that anyone merely “accused” of an offence would be added, as well as anyone “charged” with a race crime.

The Taking the Initiative Party was formed in summer in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests.

Worth reading in full.

“Mask Exempt” Lanyards

We’ve created a one-stop shop down here for people who want to buy (or make) a “Mask Exempt” lanyard/card. You can print out and laminate a fairly standard one for free here and it has the advantage of not explicitly claiming you have a disability. But if you have no qualms about that (or you are disabled), you can buy a lanyard from Amazon saying you do have a disability/medical exemption here (takes a while to arrive). The Government has instructions on how to download an official “Mask Exempt” notice to put on your phone here. You can get a “Hidden Disability” tag from ebay here and an “exempt” card with lanyard for just £1.99 from Etsy here. And, finally, if you feel obliged to wear a mask but want to signal your disapproval of having to do so, you can get a “sexy world” mask with the Swedish flag on it here.

Don’t forget to sign the petition on the UK Government’s petitions website calling for an end to mandatory face masks in shops here.

A reader has started a website that contains some useful guidance about how you can claim legal exemption. Another reader has created an Android app which displays “I am exempt from wearing a face mask” on your phone. Only 99p, and he’s even said he’ll donate half the money to Lockdown Sceptics, so everyone wins.

If you’re a shop owner and you want to let your customers know you will not be insisting on face masks or asking them what their reasons for exemption are, you can download a friendly sign to stick in your window here.

And here’s an excellent piece about the ineffectiveness of masks by a Roger W. Koops, who has a doctorate in organic chemistry. See also the Swiss Doctor’s thorough review of the scientific evidence here.

The Great Barrington Declaration

The Great Barrington Declaration, a petition started by Professor Martin Kulldorff, Professor Sunetra Gupta and Professor Jay Bhattacharya calling for a strategy of “Focused Protection” (protect the elderly and the vulnerable and let everyone else get on with life), was launched in October and the lockdown zealots have been doing their best to discredit it ever since. If you googled it a week after launch, the top hits were three smear pieces from the Guardian, including: “Herd immunity letter signed by fake experts including ‘Dr Johnny Bananas’.” (Freddie Sayers at UnHerd warned us about this the day before it appeared.) On the bright side, Google UK has stopped shadow banning it, so the actual Declaration now tops the search results – and Toby’s Spectator piece about the attempt to suppress it is among the top hits – although discussion of it has been censored by Reddit. The reason the zealots hate it, of course, is that it gives the lie to their claim that “the science” only supports their strategy. These three scientists are every bit as eminent – more eminent – than the pro-lockdown fanatics so expect no let up in the attacks. (Wikipedia has also done a smear job.)

You can find it here. Please sign it. Now over three quarters of a million signatures.

Update: The authors of the GBD have expanded the FAQs to deal with some of the arguments and smears that have been made against their proposal. Worth reading in full.

Update 2: Many of the signatories of the Great Barrington Declaration are involved with new UK anti-lockdown campaign Recovery. Find out more and join here.

Update 3: You can watch Sunetra Gupta set out the case for “Focused Protection” here and Jay Bhattacharya make it here.

Update 4: The three GBD authors plus Prof Carl Heneghan of CEBM have launched a new website collateralglobal.org, “a global repository for research into the collateral effects of the COVID-19 lockdown measures”. Follow Collateral Global on Twitter here. Subscribe to the newsletter here.

Judicial Reviews Against the Government

There are now so many legal cases being brought against the Government and its ministers we thought we’d include them all in one place down here.

The Simon Dolan case has now reached the end of the road.

The current lead case is the Robin Tilbrook case which challenges whether the Lockdown Regulations are constitutional. You can read about that and contribute here.

Then there’s John’s Campaign which is focused specifically on care homes. Find out more about that here.

There’s the GoodLawProject and Runnymede Trust’s Judicial Review of the Government’s award of lucrative PPE contracts to various private companies. You can find out more about that here and contribute to the crowdfunder here.

And last but not least there was the Free Speech Union‘s challenge to Ofcom over its ‘coronavirus guidance’. A High Court judge refused permission for the FSU’s judicial review on December 9th and the FSU has decided not to appeal the decision because Ofcom has conceded most of the points it was making. Check here for details.

Samaritans

If you are struggling to cope, please call Samaritans for free on 116 123 (UK and ROI), email jo@samaritans.org or visit the Samaritans website to find details of your nearest branch. Samaritans is available round the clock, every single day of the year, providing a safe place for anyone struggling to cope, whoever they are, however they feel, whatever life has done to them.

Shameless Begging Bit

Thanks as always to those of you who made a donation in the past 24 hours to pay for the upkeep of this site. Doing these daily updates is hard work (although we have help from lots of people, mainly in the form of readers sending us stories and links). If you feel like donating, please click here. And if you want to flag up any stories or links we should include in future updates, email us here. (Don’t assume we’ll pick them up in the comments.)

And Finally…

This ad for Alaskan Airlines, promoting draconian lockdown policies with happy, smiley faces, feels like a parody – what authoritarian propaganda would look like if America was a Communist country. But it’s real (we think). Breathtakingly awful.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

They had no honour to disparage, or rather the honour given to them by fate/God they have disparaged themselves.

The UK won’t be far behind – Fishy will be accusing of tearing the country apart.

This is quite staggering information from Eugyppius, but I don’t understand why the lawyers defending those German citizens’ freedom of speech are not using Article 5 to do so. It does seem that judges and lawyers everywhere have abandoned all sense of justice and professional standards, in order to conform to the evil Globalist agenda.

In the UK our judiciary has been bought, ir at least three quarters of it has.

He quoted only the first paragraph from it. The other two are

The latter paragraph is code language for state-sanctioned history of the time between 1933 and 1945 must not be questioned. And this state-sanctioned history is quite malleable. The present consensus is roughly that every German alive at that time was a criminal mass murderer¹, regardless of what he or she actually did, unless executed for political crimes. This used to be much less agressive while more people from that period were still alive.

¹ Explictly including toddlers. There’s no escape from the crime of having chosen one’s parents wrongly.

Wow. Thanks for that startling information. It makes me wonder how many Indigenous Germans have ever read “Hellstorm” by Thomas Goodrich.

Probably not many. And this decidedly against the political ideology of the German governing caste. For instance, one of their principal projects is turn all sites dedicated to commemorating the bombing victims into sites celebrating (that’s the right verb here) German guilt “because Germany started an illegal war.”

Incredible. If Hitler had been a true German patriot (well, Austrian), he would have worked hard to build Germany into a great nation. Instead, the Illuminati agent invaded 20 other countries to start WW2 and depopulate Europe. Even his own German generals tried to kill him to save the German people from his deliberately disastrous decisions, to no avail.

Putin & his secret mate Zelensky are doing the same now: exterminating Ethnic Europeans for the Globalists.

Art, science, education and teaching are free.

This should have been Art, science, research and teaching are free.

Germany, like the Uk, France, Italy, bought and paid for by the WEF. It is only a matter of time before total collapse unless the people still asleep, wake up. Anyone notice the CDC just decided to let the people know to treat covid, “like the flu”. See how simple it is to jerk the chains around necks? When trump said it was like the flu, four years ago, he was blasted by the bought and paid for press and our corrupt health agencies. The house of cards is slowly falling. I wish Germany all the best. But be certain, it will only happen with the dill of the people.