The Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre collates clinical data from all the intensive care units in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. The data input is done by intensive care specialists, so is probably as accurate as it is possible for a clinical audit to get.

On October 9th, ICNARC released a report on all confirmed Covid patients cared for in ITUs since September 1st and compared their finalised outcomes and data with those patients admitted before August 31st. Non-medical readers should note that these are the very sickest patients with Covid – the vast majority of Covid patients admitted to hospital never need intensive care and the vast majority of patients who contract Covid never need to go to hospital at all.

There are some striking differences between the two data sets.

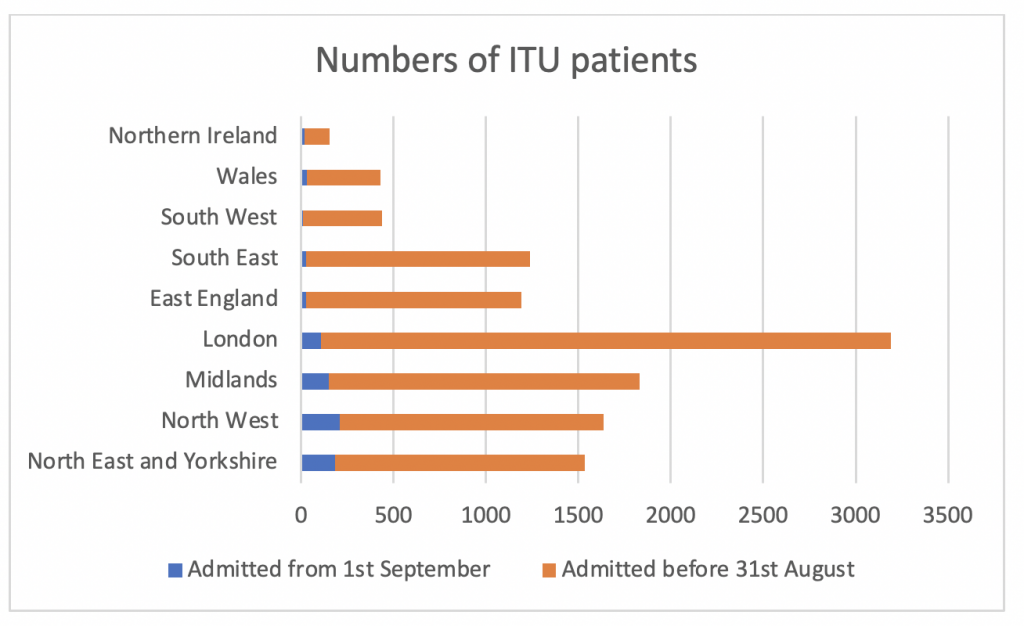

856 patients were admitted between September 1st and October 8th – the majority in the North West, North East and the Midlands, compared to 10,894 admitted before August 31st (see graph 1)

The median and mean ages of both groups were similar (approx. 60) as was the gender split (70% male) and ethnic mix.

There was a slight increase in the social deprivation index and degree of obesity in the group admitted after September 1st. The co-morbidity mix was roughly comparable between the two groups.

ITU data is very complex to assess, even for specialist medical staff, but there are a few clear differences between the two groups.

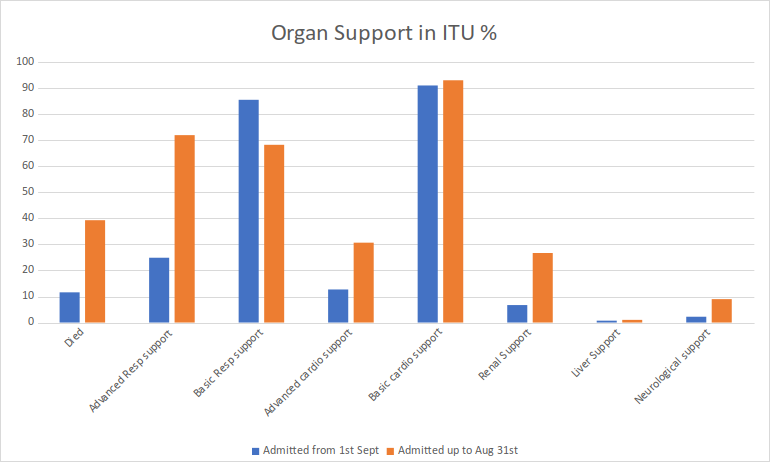

The first and most obvious difference is the death rate – 39% up to August 31st and 11.6% from September 1st. It should be noted however that this is almost certainly skewed to a lower mortality in the second group as half of the total patients admitted since September 1st are still in intensive care and some of those may not survive.

The next difference was the need for advanced ventilatory support with mechanical ventilation or CPAP. In the first group, this was needed in 72%, in the second group in 24%. Renal support with haemodialysis or filtration was also much reduced in the later group – 26.7% vs 6.7%.

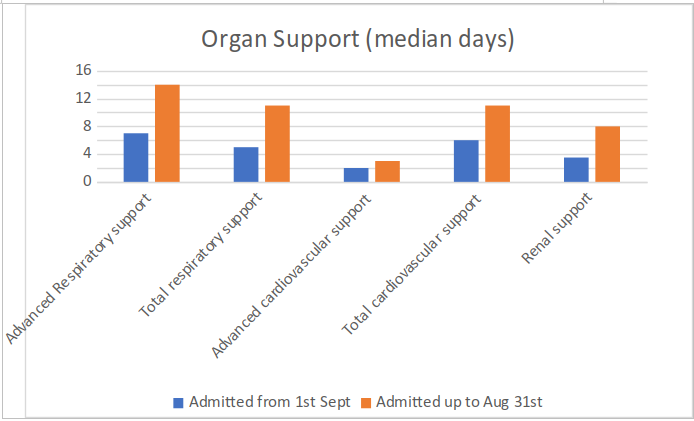

Graph 3 shows the duration of organ support needed by patients in the two groups. There is a clear shorter duration of intensive care needed in the group after September 1st.

So, what does all this mean?

On the face of it, patients admitted since September 1st seem to be less ill, require less medical support and have a much lower death rate than those admitted in the period up to 31st of August. This is perhaps not surprising, since we now know that early mechanical ventilation is probably not a good idea, and we also know that drug treatments such as dexamethasone and anti-coagulants are beneficial.

Patients not needing mechanical ventilation are a lot easier to manage than patients on ventilators. The nursing intensity is lower – this could have important implications if the trend continues, as a shortage of specialist nurses was a major problem in the London area in April and May. The large reduction in the need for renal support is also significant in reducing the requirement on nursing and medical resources.

How sure can we be that the group analysed since September 1st will be reflective of the patients admitted for the remainder of the year?

Well, there are some confounding variables which may suggest that this subgroup analysis is a bit skewed to the optimistic side. Firstly, only 427 of the 856 patients in the Sept 1st group have had completed datasets – the remainder are still being treated. It is possible that the 427 contains a higher proportion of patients who recovered quickly, and thus skewed the results to the good side. But the 427 also includes 99 patients who died and this might be a higher proportion than in the still being treated group.

There was a slightly shorter length of stay in hospital before being admitted to ITU in the group after Sept 1st (two days) than in the group admitted up to August 31st (2.5 days). Faster ITU admission and earlier intensive care might be expected to result in better outcomes.

Further, it may also be the case that as the cohort admitted after September 1st were in hospital at a less stressful time, they may have received more medical and nursing attention than the group before August 31st when resources were more stretched.

On the other hand, recent reports broadcast today from North West England and from Italy and France all tend towards a 25% incidence of mechanical ventilation compared to a much higher rate earlier in the year. If this trend continues, it would have significant beneficial effects in reducing medical and nursing workforce demands and enhancing hospital resilience.

Should there be a major ‘second wave’, it’s possible that these better outcomes may not be sustained because medical and nursing staff will come under increased strain. Having said that, the recorded differences to date are so striking and the outcomes so different that it is unlikely to be a chance effect.

So, in summary – it’s too early to tell for sure, but the initial data shows a pleasing improvement in overall survival and a reduced need for intensive medical interventions in the sickest group of COVID-19 patients. Let’s hope this trend continues.

Readers wishing to assess the data themselves can find it here.

Donate

We depend on your donations to keep this site going. Please give what you can.

Donate TodayComment on this Article

You’ll need to set up an account to comment if you don’t already have one. We ask for a minimum donation of £5 if you'd like to make a comment or post in our Forums.

Sign UpHMP Uni

Next PostLatest News