Back in March we were facing a potentially apocalyptic scenario. An unknown and lethal disease, against which we had no immunity, was starting to run wild across the world with Europe apparently worst affected.

At minimum, health systems would be at risk of collapse and some forecasts of the potential death toll put it at half a million in the UK alone. Shortages of basic foods and other essentials stoked real fears of supply chain breakdown, hunger, social unrest and worse.

In response, our society and economy were effectively suspended. As a grateful public, we clapped and whooped in the street as we submitted ourselves to an unprecedented curtailment of our personal liberties. We accepted the inevitable temporary damage to our lives and livelihoods, and to our children’s education, as necessary in the face of such a grave threat.

This was partly because we were afraid, and partly because the goals and logic of public policy were clear. The message ran like this: “We can’t prevent the disease from running through the population until a vaccine is available. This will take until 2021, so in the mean-time we must slow its progress, flatten the curve and make sure that our health systems don’t become overwhelmed.”

Implicitly, once the main wave was successfully suppressed, we could progressively release restrictions and allow the disease to take its course at a manageable level until a vaccine arrived.

By early summer across the continent these objectives had been achieved. Thousands of hospital beds and ventilators lay empty as infections and deaths dropped away. Mounting global evidence showed the disease to be far less lethal than first feared. Treatments had improved dramatically with experience. Hospital PPE shortages had been solved. Social distancing measures were being applied. Mass testing was available and vaccine trials were underway.

Bit-by-bit, just a few elements of normal life were allowed to return.

At this stage it was foreseeable that these relaxations carried the risk of some increase in infection and also that vastly increased daily testing volumes would amplify this effect.

But given the progress achieved and the mounting evidence of massive harm to other forms of health, to the economy and to many other aspects of our society it was surely time to accept a degree of increased infection, as a necessary cost of a partial return to normal.

But somewhere along the line this sober and realistic approach to managing the disease post-first-wave and pre-vaccine seems to have been forgotten.

The second wave of reported Covid infections we have seen across Europe should be neither a surprise nor any great cause for alarm. But instead of a measured response, balancing all considerations and planning for the long term, we’ve been subjected to hasty and high-handed panic-measures. These range from the UK’s ruthless quarantine ambush of those who dared to take a holiday abroad to the Spanish government’s national edict to wear masks when anywhere outdoors, even when totally alone. Every day we were admonished with the threat of stricter measures unless infections return to somewhere near zero.

What justifies this new approach? Are we seeing a greater proportion of Covid deaths associated with these increases in reported infections?

No, we are not. Quite the reverse in fact. There is something fundamentally less dangerous about the recent waves of reported infections than the first.

The data from Spain illustrates the point. A clear second wave of reported infections is not matched by any increase in daily deaths, which remain close to zero.

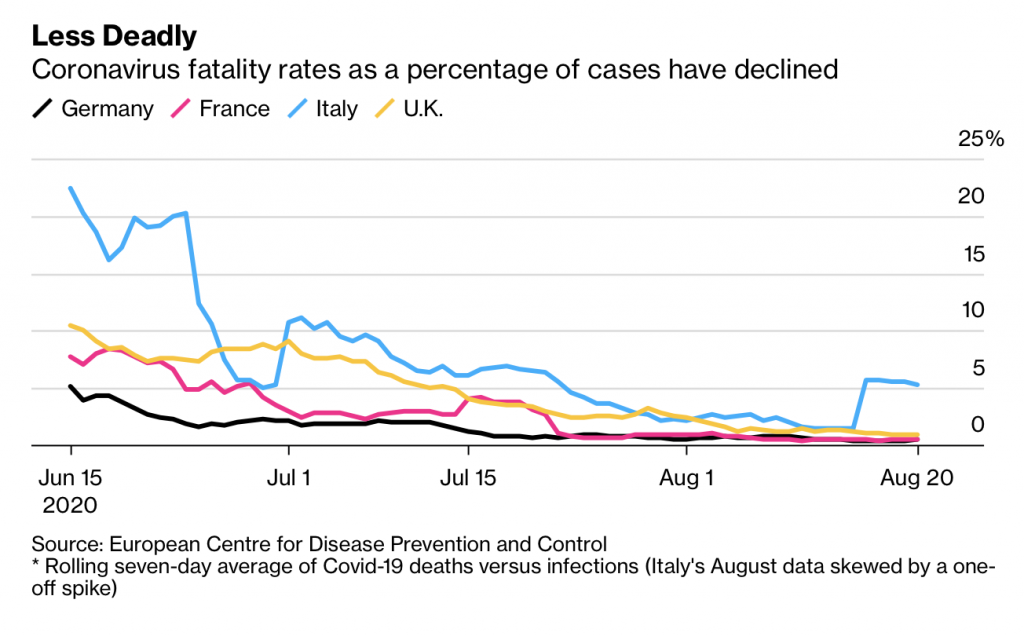

It’s not just Spain. The data on the mortality percentage of the first wave vs the second and the pattern across Europe is striking.

As a side note, it’s interesting that the USA, that supposed beacon of public health dysfunctionality, has a lower overall mortality rate than most European countries and has had a similar sharp drop in recent weeks.

Governments in Europe urgently need to restore calm and balance to their decision making and get back in front of the situation. That means setting realistic public health objectives now as part of a coherent plan to minimise the emerging catastrophic harm to our overall health and wellbeing caused by the lockdown.

Donate

We depend on your donations to keep this site going. Please give what you can.

Donate TodayComment on this Article

You’ll need to set up an account to comment if you don’t already have one. We ask for a minimum donation of £5 if you'd like to make a comment or post in our Forums.

Sign UpLatest News

Next PostHow to Live With Risk in the COVID-19 World