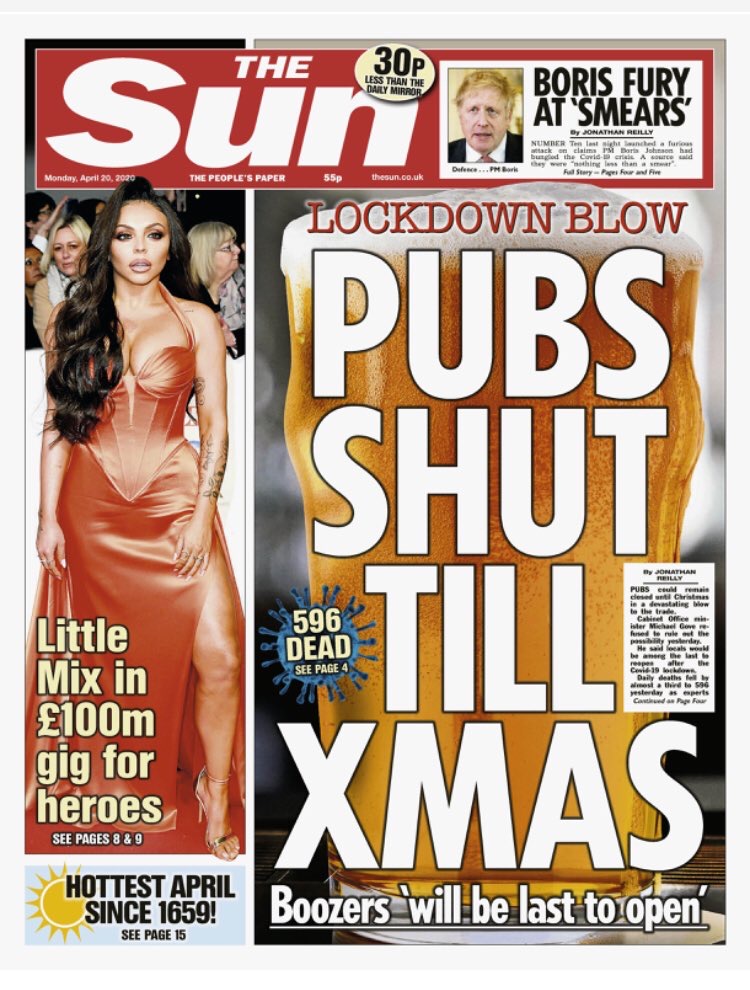

Terrible news in this morning’s Sun: pubs won’t re-open until Christmas. More bad news elsewhere: according to the Times, Boris is cautious about easing the lockdown, with his “overriding concern” being to avoid a second wave of infections. (The Mail has its version of the story here.) Does this mean Professor Neil Ferguson’s proposal for “intermittent social distancing”, whereby we relax some of the restrictions in short time windows, then reimpose them when case numbers rebound, has been rejected? That was put forward in Ferguson’s March 16th paper as the only viable alternative to leaving the lockdown in place until a vaccine becomes available. Bad news on that front, too. On Saturday all the papers got excited about the fact that a vaccine might be available by September – Sarah Gilbert, Oxford’s Professor of Vaccinology, announced she was “80% confident” it would be work – and trials are about to get underway. But yesterday Sir Patrick Vallance poured cold water on that idea, pointing out that no vaccine can be approved until we know it’s completely safe. In an article for the Guardian he writes: “A vaccine has to work, but it also has to be safe. If a vaccine is to be given to billions of people, many of whom may be at a low risk from COVID-19, the vaccine must have a good safety profile.” Professor Gilbert has acknowledged that accelerating the approvals process to make the vaccine available by September might require emergency legislation so it can be given to high-risk groups before it’s fully licensed.

Gavin Williamson, the Education Secretary, gave the Government’s daily briefing yesterday, and refused to be drawn on the Sunday Times‘s claim that schools would reopen on May 11th. According to several papers today, the earliest they will re-open is after the summer half term, which is June 1st. That’s bad news for all sorts of reasons, not the least of which is that two-thirds of schoolchildren aren’t logging on for online lessons according to a report by the Sutton Trust and Public First. Here’s the killer finding, as reported by Camilla Turner in the Telegraph: “Half of teachers in private schools said they are receiving more than three quarters of work back, compared with 27% in the best state schools, and just 8% in the least advantaged state schools.” More evidence that the lockdown is harming the most disadvantaged.

Several readers have sent me links to articles casting doubt on the reliability of the computer models that epidemiologists, virologists and mathematicians have been using to predict the impact of the virus. This one by Michael Fumento, which is sceptical about statistical modelling in general, is particularly good. He makes the following points:

- The CDC’s model predicted that 1.4 million people would die from Ebola in Liberia and Sierra Leone five years ago. The final death toll was less than 8,000.

- The US Public Health Service predicted that at least 450,000 Americans would be diagnosed with AIDS by the end of 1993. In fact, the number was 17,325.

- In 2005, Neil Ferguson told the Guardian that up to 200 million people could die from bird flu. “Around 40 million people died in 1918 Spanish flu outbreak,” he explained. “There are six times more people on the planet now so you could scale it up to around 200 million people probably.” The final death toll from avian flu strain A/H5N1 was 440. (That’s 440 people, not 440 million.)

- In 2002, the same Professor Ferguson predicted that mad cow disease could kill up to 50,000 people. It ended up killing less than 200.

One reader – David Campbell, a law professor at Lancaster University – has given me permission to republish his paper, first published in 2003, analysing the Labour Government’s response to the foot and mouth disease epidemic in 2001. That, too, was informed by the work of Professor Ferguson. Needless to say, it’s very critical. You can read that paper here.

Some of you may recall the gloomy prognosis that Professor Anthony Costello gave to the House of Commons Health Select Committee on Friday, claiming we wouldn’t achieve herd immunity until after eight to ten waves of infection, with a death toll exceeding 40,000 in the first wave alone. This prediction was based on a Dutch survey of blood donors which showed that only 3% of them had developed antibodies to the virus. One reader has got in touch to point out that blood donors are unlikely to be a representative sample. He writes:

By definition, a blood donor has no known infections, has not had a recent illness, even a cold or flu, and I presume the blood banks are being particularly careful at present. Even if the tests are done from the initial samples rather than the blood collected (i.e. includes rejected donors), someone who is aware that they had a cough recently would either not have volunteered or been rejected at questionnaire stage before giving a sample.

Knowing how many people have been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 is important because without that number we can’t calculate the infection fatality rate (IFR). But we can be pretty confident it’s lower than the case fatality rate (CFR), which is worked out by dividing the number of people who’ve tested positive by the number of deaths. The CFR of H1N1 influenza (swine flu) varied from 0.1% to 5.1%, depending on the country. Its IFR turned out to be 0.02% according to the WHO. The IFR of SARS-CoV-2 is likely to be higher than that, but not nearly as high as the CFR in countries like Italy, Spain, Belgium, the UK and the US. Oxford’s Centre for Evidence Based Medicine (CEBM) has updated its estimate of the IFR, which it now puts at between 0.1% and 0.36%, i.e. in the same ballpark as seasonal flu. That estimate is still heavily contested, but as we do more serological testing and continue to revise upwards our estimates of the number of people who’ve been infected the IFR keeps falling. Dr Jay Bhattacharya, Professor of Medicine at Stanford and one of the architects of the serological survey in Santa Clara that showed the number of people who’ve been infected is between 50 and 85 times greater than the number of confirmed cases, has given an interview to Peter Robinson at the Hoover Institute that you can watch on YouTube here. The preprint detailing those findings estimated the IFR at between 0.1% and 0.2%. “It’s probably about as deadly as the flu, or a little bit worse,” Professor Bhattacharya tells Robinson. (If you want to read a detailed critique of that paper, see this comment in a Columbia University forum.)

Mike Hearn, a reader, has an interesting hypothesis about why deaths-per-million in Sweden (150) are higher than in Norway (30) or Denmark (60). He points out that darker-skinned people are over-represented in America’s death statistics. For instance, in Illinois 43% of people who’ve died from the disease and 28% of those who’ve tested positive are African-Americans, a group that makes up just 15% of the state’s population. Why should this be so? The most popular theory is that it’s due to America’s “systemic racism” – African-Americans have below-average incomes and less access to healthcare, they’re more likely to be discriminated against by healthcare professionals, they have less living space than Americans of European ancestry and are therefore less likely to self-isolate, etc. But what if it’s because people with darker skins produce lower amounts of vitamin D? A recent letter in the BMJ flagged up this possibility. The writer of the letter, Robert Brown, has co-authored a paper on this you can read here. If it turns out that darker-skinned people are more susceptible to the virus than light-skinned people, that would explain why there are a higher number of deaths-per-million in Sweden than its neighbours – because it has a higher immigrant population. Twenty-five per cent of Sweden’s population – 2.6 million of a total population of 10.2 million – is of recent non-Swedish descent, whereas only 14% of Norway’s population is of non-Norwegian descent. (There are ~70,000 Somalians in Sweden and only ~11,000 in Denmark.) Incidentally, the latest daily death toll in Sweden is 29.

A reader drew my attention to an interesting critique of the Government’s handling of the crisis by a couple of vets entitled ‘Vets would not manage the Covid-19 crisis this way‘. I wonder if any vets are members of SAGE? Judging from this paper, which draws on the experience of vets managing respiratory diseases in livestock, they should be.

I took the dog for a walk in Gunnersbury Park in Acton yesterday and it was more crowded than it has been at any time before in the last month. Other walkers seemed to be less circumspect about observing the two-metre rule, too. (Why metres and not feet, by the way?) My impression is that people are growing tired of social distancing, or perhaps they were just reacting to yesterday’s front pages saying that the Government is considering a phased exit.

There was one bit of good news yesterday: the latest daily death toll is 596, the lowest it’s been in a fortnight. It looks as though deaths have peaked in the UK, something that’s borne out if you compare the last seven-day average to the previous seven-day average.

Finally, thanks to all those readers who made a donation to pay for the upkeep of this website yesterday. If you’d like to make a donation to Lockdown Sceptics, please click here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

I wish I shared your optimism, Toby. The next indignity seems to be the imposition of face masks. It feels to me like a humiliating badge of compliance.

Even under lockdown and social distancing, no one can tell that you’re actually ‘going along with it’. Conceivably, at any time, no one really knows whether you’ve been out for more than an hour, or even twice that day; they don’t know you’re not going to buy something non-essential at the shop. They don’t know whether you clap at the appointed hour on a Thursday night. These are tiny slivers of freedom and dignity to cling onto.

But impose face masks, and your compliance – and shame – is unambiguously there for all to see. Not only do you have to wear the masks, but you’ll probably have to source them yourself – The Sun is even giving instructions on how to make them. Perhaps Lockdown Sceptics could have some made with an image of Neil Ferguson on them. Alternatively, perhaps, we should make them look like disgusting health hazards with apparent flakes of skin, blood and pus stains on them.

Or we could just refuse to wear them. I will do just that

Seems increasingly likely doesn’t it, just to ratchet up the fear levels another notch. Plod are going to thoroughly enjoy themselves enforcing that one.

Agreed, non compliance will be a badge of honour in my mind

And I’m not accepting their vaccine either no matter what, no matter, even if I’m excluded from society for the rest of my life, it’s just not happening. These people are not trustworthy and their exploits in India have me convinced of this. Not happening.

Amen!

On an attendant note – and no, I will not wear a face mask – what is all this bull about essential items? As far as I understand it if an item is on sale you can buy it. And that comes directly from a government that can’t really do joined up writing. It’s the Plod (not the brightest profession in the world) who have mostly mentioned non-essential items, conveniently forgetting that there isn’t a shortage of anything (well not much) and there is no rationing. And how the hell would they apply that ‘so-called regulation’ to shopping online?

Facemasks are no indignity, I will agree to wear one from the moment they decide to switch to facemasking instead of all the indignities caused by lockdowns, loss of our rights and loss of our jobs. I suggest we make a priority of removing irrational measures like lockdowns and dangerous police powers, replacing them with non-intrusive but effective measures like face masks, wash basins, open windows instead of air-con, copepr plated door handles and more regular public transport to reduce crowding is the right step to take.

Wearing a yellow star was considered non intrusive in 1939

Firstly, everyone would wear facemasks, they wouldn’t be of “yellow star” type use to mark out those a government wishes to oppress. Secondly a facemask is also a useful defence against facial recognition surveillance cameras, quite good for making state intrusion trickier for them. Unlike a yellow star beng used to track you a facemask makes tracking harder. We need to be willing to give ground on minor things like facemasks, things that actually hep make a difference but don’t restrain our important rights, in exchange for making the forces of government give ground on the intrusive measures, make a deal of it, we will take every reasonable precaution to stop the spread, as soon as they stop forcing unreasonable precuations upon us. We have to show that our way is effective and workable without needing their intrusion, that way mroe people will come to see the sense of our anti-lockdown, pro-liberty, pro-business cause.

When would the enforced face mask law be lifted? The one that says that a person when outside the home needs to cover their face, even when walking alone in the countryside – because if we make it optional or common sense, some people will take them off when sunbathing in parks and that wouldn’t be ‘fair’.

If it’s just a ‘minor thing’, why would that rule ever be lifted? At any time there could be a new virus with pre-symptomatic shedding, so it would pay dividends for people to have to wear face masks all the time – even in the home come to think of it.

With regards to facial recognition, there’s no problem because each citizen could eventually be issued with personalised bar-coded face masks.

If face masks are made mandatory for certain activities, and it proves impractical in some circumstances not to comply, a design of protest face mask would be useful. At least people could feel like they have stated a view and are not simply endorsing the rule.

Suspect facial hair might be in vogue, as we know it makes face masks virtually useless!

Will masks be required ‘in the bedroom’ (asking for a friend)

Dark glasses might me more appropriate in my case

Read Dr John Lee’s article on this subject in the Spectator.

He contends that even surgical grade face masks are designed to filter bacteria – not viruses, which are typically ten times smaller.

A cloth face mask has pores in the weave that are 1,000 to 5,000 times larger than a typical coronavirus – pretty much an open door to them.

Masks do almost nothing to protect you, but they do ensure that if you catch it then your breath, the spit while you talk and your sneezes coughs travel less distance. They let us mingle in society (with basic 2m social distancing) in a way which makes viral spread a lot trickier, as particles (the virus clings to saliva droplets far bigger than the viral particles themselves) travel a lot less distance if a mask slows their exhaled velocity first. Facemasks are a good alternative to lockdowns.

Being forced to wear a mask would be the final straw for me and I would refuse too. Besides if they can’t find enough for the NHS where on earth do they think we’re going to find them?!

Hi Paul,

I understand your frustration. I thought the same. But after, I read an article somewhere. A doctor said that my mask protects others and their masks protect me. So my mask is not for me. It is more for anybody else around me.

For me, it was a reasonable argument.

If I get the choice, masks or lockdowns I pick masks. We need to be clear that in resposne to lifting lockdowns we will take the sensible health pre-cuations necessary, this is a good offer to negotiate with. You end lockdowns, we wear masks. You re-open all the pubs for takeaway service, we wash our hands even more often. You re-open our jobs, we’ll use some spare time to deliver food to the old people who might actually be at some risk if they caught the disease. And so forth, for each intrusive measure the government removes, we accept a non-intrusive one.

Thank you Toby for your brilliant research and journalism. This website gives us all hope and shows that not everyone is paralysed by fear and led by an irrational response.

I still can’t understand why Neil “Haven’t Got A Clue” Ferguson carries such weight in government decision making. His track record is nothing short of abysmal! The man has no understanding of the importance of the economy nor the non-Covid healthcare crisis this totally unnecessary lockdown is creating.

Would happily mount a campaign or petition to get him sacked/removed from his position for his indeed abysmal track record.

I am constantly looking for a campaign/action group but this is the only page I am a member of right now. I am a lawyer/teacher and writer and would happily protest in the streets (but of course the Coronavirus Act makes this illegal (unlike the Civil Contingencies Act which we chose not to use). Are there any organised protests in the UK?

I have never in my life considered protesting but would strongly consider it now, unfortunately I have no idea about how to go about it and am not aware of any groups, Reddit might be a good place to look. Convenient that it should be made illegal, however I am almost at the point of not caring because it will generate attention.

I remember some time back there was a website trying to organise a protest in early April against the lockdown and it got taken down pretty quickly

If the Americans can do it, why can’t we?

P.S. If anyone wishes to make their thoughts on Professor Ferguson’s “model” known to him personally, he is on Twitter: @neil_ferguson

Toby, your updates are extremely helpful. In my view, the single most mendacious aspect of the globally adopted propaganda here is the use of deaths “with” as opposed to deaths “from”. The distinction is drawn parenthetically (occasionally), but my understanding is that the degree to which this is misleading is proportional to how widespread the disease is. If 50% of the population has it, one would expect at least 50% of deaths to be part of the rising “Covid-19 death toll”.

I believe the solution (for the UK, at least) lies in simply looking at the year-on-year comparison of deaths whose underlying cause is respiratory disease. These have been recorded for ten years, and, as I understand it, must include all deaths that were actually caused by Covid-19. ONS will release w/e 10th April tomorrow, which will be interesting because there definitely was a spike w/e 3rd April (week 14), and how that spike continues will give a good idea about true excess mortality. The numbers lag because they are by date of registration, so not only is the availability of data a week behind, but also the deaths that it describes may be up to two weeks old.

However, at at the end of week 14, the total number of deaths from respiratory failure (which we have to assume includes those actually caused by Covid-19) was 25,012. At the same point in 2018, the figure was 31,659.

It may be that we do see a significant spike in the coming weeks, and that 2020 starts to compare with, or even exceeds 2018. If we do see that, the conclusion would be that the effect on mortality was slightly worse than a very cold winter.

I have been producing the graphs each week (as have others, e.g. https://twitter.com/hector_drummond/status/1251177611100913664 and https://twitter.com/hector_drummond/status/1251176564051640320). I think it would be great to include this in your next update.

Thank you so much for your calmness and rationality. I am baffled at the country’s reaction to this. How can we get this data out to a wider audience and/or organise a protest on this?

A very big daily thank you Toby for your work.

If nothing else, it’s reassuring to know that there are others who question this crazy approach taken by our cowardly government.

I’m off for a longish walk than usual this afternoon. This is following the new interpretation of the guidelines, that as long as I walk for longer than the drive to it then I’m fully compliant.

I’m wondering how far I can stretch things? Its a 9 hour round trip drive to the Lakes for me, so as long as I walk for 9 hours and 1 minute then I’m good! A trip to Scotland maybe pushing it a little though …

On the subject of IFR, has anyone heard any results from the Porton Down antibody survey?

On 3rd April Matt Hancock said (note past tense “We have already”): “Yes, but I’m not assuming any come on stream – that’s pillar three, as we call it – in order to hit the 100,000 target. We have already 3,500 a week of antibody tests at Porton Down, and they are the top quality, the best test in the world. We’re using those for research purposes to understand how much of the population has had coronavirus. This is one of the great unknown questions. But that’s obviously a very small number, 500 or so a day.”

Anyone got any idea why the Porton Down laboratory has the Health Secretary listed as a 75% of more shareholder?

I walked to and along Poole & Bournemouth promenade yesterday, definitely a good deal more people, cyclists and cars about than a week previously, Easter Sunday. In the absence of much evidence of Covid in the local Dorset area, suspect many are beginning to suffer from Lockdown fatigue. Guido reporting increasing incidence of anti-lockdown demonstrations around the World. As ever (see Brexit and ‘Climate Emergency’ the noisy woke, the MSM, ‘celebrities’ and social media jockeys give the impression that the vast majority are ‘on board’, I suspect (hope) the level of cynicism is underreported.

Update, I just took a sunny, late afternoon drive around the Sandbanks peninsula, it wasn’t essential, I didn’t need to or have to, I just wanted to, for my own pleasure. Felt good.

Sounds to me like you didn’t actually encounter any other human beings, hence no risk of spreading in either direction. No civilised person could comdemn you for those actions. I wish this text field would let me underline the word “civilised”, today I define it to mean any person who can understand statistics and respects that a risk of death always exists hence quality of life is more important than quantity.

There is some racial data for the UK. According to the Guardian, nearly 25% of patients critically ill are Asian or black, versus 16% for black and Asians in the general population. For the at-risk age group, that 15% is much lower. I doubt if it is Vitamin D. It is far more likely to be obesity, diabetes and hypertension, all of which have significantly higher incidence in blacks and Asians than whites and all of which increase the risk of COVID. There may also be genetic disposition, particularly around ACE2 in the lungs. I have heard (but seen no data) that the Somali population in Sweden is disproportionately affected, and may be in London too. I note that the UK has the largest Somali community in Europe.

Doesn’t it just reflect the ethnic composition of London, where most of the cases are? London has a majority ethnic minority population. Plus poverty and high density living I imagine.

Hi Phoenix44

Re effects of covid on Sweden’s Somalis, Go to BMJ link in Young’s blogabove.

ATB

Here are 53 measures we can take right now to end the lockdown and reopen the economy and public life while continuing to limit the damage COVID-19 is doing: https://medium.com/@codecodekoen/covid-19-53-suggestions-for-reopening-the-economy-in-a-responsible-way-f8616bb2cf83

I have written to my MP to advise him that I will not accept the shutdown for my age group till 2022. I am a fit pensioner at the moment, and dread to think how I would survive or not if this length of time was imposed upon me. Among my friends the fear factor is running very high at the moment and I am worried some may not be able to last such a long period of time in lockdown. I am very positive regarding this virus, I will not let it beat me or worry me but unless the Government change this plan many elderly will worry themselves into an early grave.

Christine, I do hope your MP has the courage of conviction to accept and represent your point of view. The emotive rhetoric surrounding this “deadly virus” seems to have been engineered so as to discourage any form of critical thought or rational discourse.

There was a move at the start to adopt a measured and proportionate approach to tackling this “crisis” with the aim of building a “herd immunity”. Unfortunately, that gave way to an irrational knee-jerk response that has only reinforced the herd mentality.

You may wish to check Fumento’s points a bit more carefully yourself before citing them, as the points you’ve pulled out contain serious errors or mischaracterizations of what was written in the papers. To pull out a couple of examples:

The paper citing 1.4 million deaths for Ebola stated that it was for *four months* of uncontrolled or unmitigated behaviour and multiplying by 2.5 to estimate for unreported occurrences and used this as a justification for taking countermeasures and the importance of putting mitigations in place as early as possible. A few sentences after the 1.4 million figure, it goes on to say “The cumulative number of Ebola cases for Liberia and Sierra Leone could double to approximately 8,000 by the end of September 2014”, which is somewhat closer to the 8,000 you quote and something of a justification of the model.

The error with AIDS reporting is even greater; the 17,325 cases in 1993 is from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/8010413_Migration_and_AIDS_in_Mexico_An_overview_based_on_recent_evidence and is actually the number of cases in Mexico, not the United States which by mid 1993 had 315,390 cases. It’s difficult to understand how such a fundamental error was made in the first place and is not the kind of error made in a “particularly good” article; you may wish to raise your quality threshold somewhat.

The point made, though, is a good one and still stands:

‘Use and abuse of mathematical models: an illustration from the 2001 foot and mouth disease epidemic in the United Kingdom.’

‘‘The progress of an outbreak of FMD is extremely difficult to predict in the early stages of the disease. The course of an outbreak can be critically affected by minor and inherently unpredictable events, such as a single livestock movement. For this reason, predictive disease models, which depend on statistical probabilities of transmission, have not met with much success in predicting the spread of FMD from herd to herd, and still less the impact of

control measures……….’

‘The UK experience provides a salutary warning of how models can be abused in the interests of scientific opportunism.’

https://europepmc.org/article/med/16796055

The point (or at least Young’s point which appears to be that models don’t work very well) doesn’t stand if several of the papers cited actually do make good predictions and the author is either deliberately misrepresenting them or has made a mistake so inpet that they’ve confused the USA and Mexico and *still* doesn’t spot it after seeing the absurdly low resultant infection rate. Even if you don’t like Ferguson’s work, the vCJD deaths that occurred are inside the 95% confidence interval of the paper cited in the article of 50 – 50000, the very high CI is the reason that the second sentence of the abstract says “well grounded mathematical and statistical models are therefore essential to integrate the limited and disparate data” which Young & Fomento have missed, as well as the lower bound number completely and not taking into account that it was even before any bovine to human transmission had been detected at all.

There may be things to criticise in the COVID-19 modelling which can be done by criticising the actual models, starting parameters or the maths themselves, which Young doesn’t do. Picking out a policy failure aruond FMD, an animal disease, from nearly two decades ago says nearly next to nothing about the current situation. Yes, predictive modelling in the early stages is hard as they’re very sensitive to initial conditions and real world outcomes are affected by behaviour and policy changes. But the government has to have a policy response (even if that is a do-nothing, no-response) which if it isn’t guided by models is going to be guided by…what exactly?

“… the government has to have a policy response (even if that is a do-nothing, no-response) which if it isn’t guided by models is going to be guided by…what exactly?”

The 64 trillion dollar question. Maybe it has to be the result of rationalism, not empiricism. The ‘science’ doesn’t replace the need for judgement calls – it merely disguises or defers them. I don’t think it even ‘informs’ them when it is so obviously confused itself.

Sweden used cool, calm rationality in deciding that the disease would have to be a factor of ten worse than indications (possibly just anecdotes) were showing it to be, in order to justify destroying the economy and suspending civil liberties. One factor was, apparently, that they could see that a lockdown is a self-reinforcing strategy, making it almost impossible to come out of with any sort of coherent justification. Our government is now wrestling with this this problem, meaning we are probably going to have to trash the economy and society even further while the press and public are psychologically conditioned to accept a relaxation of the lockdown.

Government actions should, in a perfect world, always be evidence based. Evidence provides data, and data can be used for decision making. Models using accurate data can indeed provide useful decision support tools. The author’s point here is straightforward: models are inherently unreliable, dependent as they are on the quality of the data provided, as his referenced paper points out:

‘Then Fauci finally said it. “I’ve spent a lot of time on the models. They don’t tell you anything.” A few days later CDC Director Robert Redfield also turned on the computer crystal balls. “Models are only as good as their assumptions, obviously there are a lot of unknowns about the virus” he said. “A model should never be used to assume that we have a number.”

Which, of course, is exactly how both a number of public health officials and the media have used the them.’

The criticism of modellers is that they themselves are aware of the limitations of modelling but may not always be as diligent as they might be in making that clear:

‘The models essentially have three purposes: 1) To satisfy the public’s need for a number, any number; 2) To bring media attention for the modeler; and 3) To scare the crap out of people to get them to “do the right thing.”’

‘……all the modelers know that no matter what the low end, headlines will always reflect the high end.’

On a separate point, the fact that a paper may be 14 years old quite obviously in no way invalidates its conclusions, most particularly when it concludes:

‘The course of an outbreak can be critically affected by minor and inherently unpredictable events, such as a single livestock movement. For this reason, predictive disease models, which depend on statistical probabilities of transmission, have not met with much success in predicting the spread of FMD from herd to herd, and still less the impact of control measures……’

That point is particularly relevant to Covid 19. Covid 19 data is all over the shop. The virus could have crossed over to humans as early as 13 September 2019 or as late as 07 December. Testing has been sporadic and unreliable. Mortality rates are unreliable, since no international standard for recording cause of death exists.

Short of good data, as they are, to input into decision support tools, leaders have to exercise judgement; and democratically accountable leaders are extremely risk averse, with the honourable exception of Sweden, which has a health authority independent of political control. Hmmmm.

Democracy: the least worst system of government.

Good data is being gathered in the U.S. Hopefully we are doing the same. Then the able bodied can all get back to work, knowing that the risks we take with this virus are really no different to those we take every year with influenza:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k7v2F3usNVA&list=PLq8BgDugd2oyqmYx6RdVlJfQeAdhJkhc3

I think we have been walked to this outcome for quite sometime. I am in no doubt the controlling powers are moving to complete population monitoring. We will no longer have freedom to buy and sell. Go outside or partake in any activity without the information being collected.

If you think back to the arrival of Alexa. In most people’s homes. The fact your phone listens to your conversations and targeted advertising appears amongst your social media. All this information is for sale.

This virus is without doubt nasty but the fear of it has been made much worse. The measures put in place to hasty and withdrawing them all I dont think will ever happen. You only have to listen to the WHO and the measures they want to take.

The rapid tell tale society that phones police re gatherings of people are doing the job for them.

I could go on. I will just say if you are not aware take a look at The Corbett report.com and the Last American Vagabond. Both put out great information on the USA and the rest of the world.

We cannot trust any death figures when they are being recorded incorrectly and the numbers will drop as the epidemic passes and the government change the recording rules to suit their message.