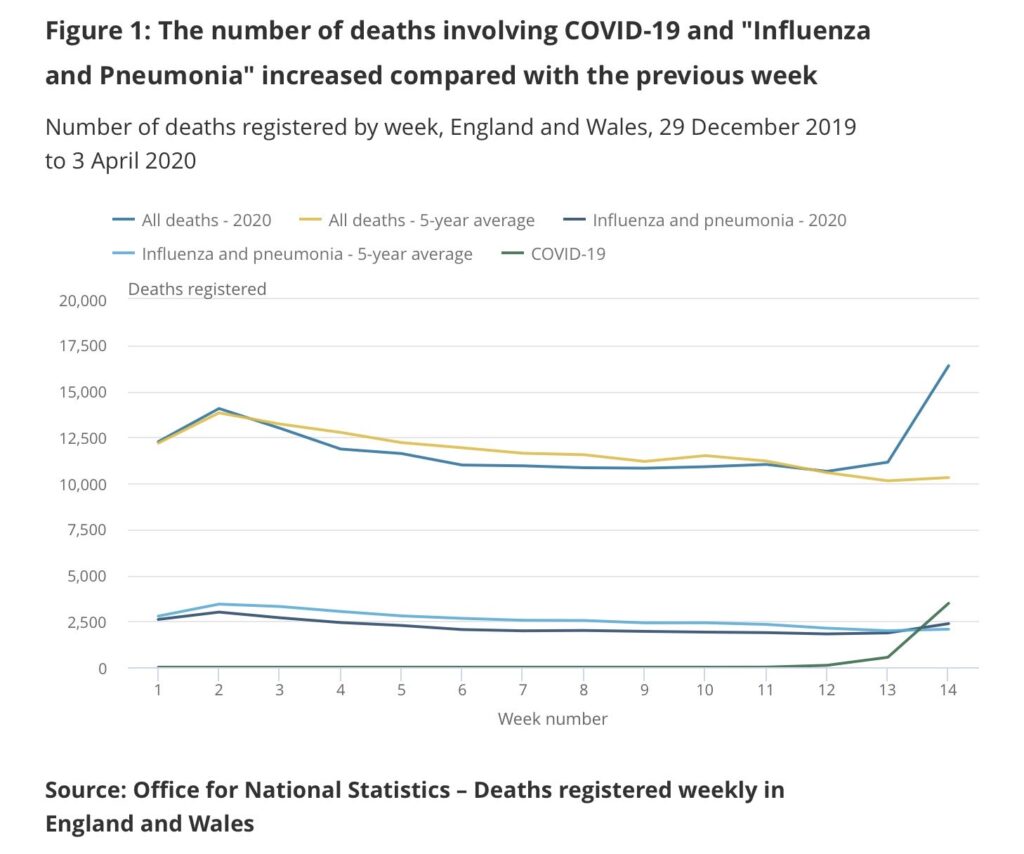

One of the stats most commonly latched on to by lockdown sceptics is the number of people who would normally be dying at this time of year in the absence of coronavirus because it seems to show there’s been no increase (or, rather, it did before the death toll began to peak). According to the ONS, deaths mentioning COVID-19, influenza or pneumonia in Week 13 of 2020 (March 20th – 27th) were 18.8% of all deaths, whereas the five year average puts deaths mentioning influenza or pneumonia at 19.6% of the total. Having said that, the total number of deaths in Week 13 this year in England and Wales was 11,141 compared to the five year average for Week 13 of 10,130 (ONS). (Lockdown began on March 23rd so the fact that deaths from COVID-19 weren’t higher can’t be attributed to that.)

Every year, about 600,000 people die in the UK and it remains to be seen whether more people will die this year than in a normal year and what effect, if any, the lockdown will have had. For instance, about 10% of people aged 80 and over die every year and while it’s true there’s a risk they’ll die if infected with coronavirus, they won’t be significantly less likely to die if they don’t catch it because they’re likely to die of something else. According to Prof Sir David Spiegelhalter, a statistician at Cambridge University: “Many people who die of COVID would have died anyway within a short period.” (Neil Ferguson told the FT at the beginning April he thought it was “plausible” that two-thirds of the people who died of the virus at that point would have died anyway later in the year.) The average age of the people who’ve died from coronavirus in the UK so far is 79.5 and a majority of them have underlying health conditions.

However, as the death toll in England and Wales has increased, this argument has become harder to make. According to the European Monitoring Excess Mortality group, which publishes weekly bulletins of the all-cause mortality levels in up to 24 European countries or regions of countries, the number of people dying in England was normal up until Week 11 of this year, but had climbed to “very high”, i.e. well above average, by Week 14. (Although still normal in the rUK.) And, of course, if it drops back down to normal the advocates of a prolonged lockdown will attribute that to the extreme social distancing measures the Government has imposed. Against that, the mortality rate was normal in Sweden in Week 14 in spite of Sweden not closing restaurants, bars or schools or banning social gatherings of less than 50 people. On April 12th, Sweden recorded just 17 new deaths from COVID-19, its lowest daily rise in a fortnight.

One complicating factor is that we don’t know how many people are dying of coronavirus, as opposed to with coronavirus. In the UK, if a patient with COVID-19 dies their death is automatically included in the NHS’s statistics. (The ONS’s record of deaths due to coronavirus includes those who’ve died outside hospital where the patient’s doctor suspects they were suffering from the virus, test or no test.) But what if COVID-19 in’t the cause of death? For instance, an 18-year-old in Coventry tested positive the day before he died and was widely reported as being the youngest victim at the time. But the hospital subsequently released a statement saying his death had been due to another “significant” health condition and wasn’t connected to the virus.

Dr John Lee, a retired professor of pathology and former NHS consultant pathologist, has written a piece for the Spectator pointing out that if someone dies of a respiratory infection in the UK, the specific cause of the infection isn’t normally recorded unless the illness is a ‘notifiable’ disease. Until coronavirus came along, the vast majority of respiratory deaths in the UK were recorded as due to bronchopneumonia, pneumonia, old age, etc. “We don’t really test for flu, or other seasonal infections,” he wrote. “If the patient has, say, cancer, motor neurone disease or another serious disease, this will be recorded as the cause of death, even if the final illness was a respiratory infection. This means UK certifications normally under-record deaths due to respiratory infections.”

Since March 5th the list of ‘notifiable’ diseases has been updated to include COVID-19 but not flu, so anyone now dying of a respiratory infection who’s tested positive is recorded as having died of coronavirus. But is that the real cause of death? It’s possible (although unlikely) that the UK is suffering from an above average number of deaths in April due to an unusually deadly bout of seasonal flu, not coronavirus. According to estimates produced by Public Health England, 28,330 people died from influenza in England in 2014/15 (although only 1,692 in 2018/19).

Another complicating factor is that the lockdown is likely to be suppressing other causes of death, such as road traffic accidents, workplace accidents, violent crime, etc – another reason the number of deaths may not be much above the five-year average since the lockdown was imposed. That is, deaths due to COVID-19 aren’t being added to an underlying total that’s in line with the five-year average, but to a total that’s lower than the five-year average due to the fact that we’re spending more time in our homes. The relevant counterfactual is a comparable lockdown absent coronavirus and nothing like that has ever happened.

International comparisons aren’t much help when it comes to determining the true number of COVID-19 deaths because different countries use different ways to collect data on coronavirus deaths and some countries are changing the way they record deaths from one week to the next. Australia, for instance, has changed its definition of a COVID-19 “case” – and therefore whether to list coronavirus as the cause of death – 12 times since January 23rd. All of this makes it hard to calculate how many lives have been saved by the lockdown.

Update: ONS Data for Week 14 (March 27th – April 3rd)

This data, showing a sharp increase in the number of deaths in Week 14, strongly suggests that COVID-19 is more deadly than seasonal flu. The five-year average for Week 14 is 10,305, whereas the number of deaths in England and Wales in Week 14 in 2020 was 16,387, and will be larger still in Week 15. Against this, if Professor Spiegelhalter is right, many of the people who died of COVID-10 in Week 14 would have died later in 2020 anyway from another cause. By the end of the year, when we have all the data, we may conclude that the effect of the virus will have been to squeeze deaths that would have otherwise have been spread out over the course of 2020 into a narrow window in March/April, without increasing the total.

Further Reading

‘How deadly is the coronavirus? It’s still far from clear‘ by Dr John Lee, The Spectator, March 28th 2020

‘Tracking the coronavirus: why does each country count deaths differently?’ by Elena G Stevillano, El Pais, March 30th 2020

‘Coronavirus: How to understand the death toll‘ by Nick Triggle, BBC News, 1st April 2020

‘Coronavirus: seven questions for public health post-mortem analysis‘, Niall McCrae and Roger Watson, Journal of Advance Nursing, April 6th 2020

‘Keeping the coronavirus death toll in perspective‘ by Heather Mac Donald, The Hill, April 17th 2020

‘Why you can’t trust the UK’s “daily” Covid19 updates‘, Off-Guardian, April 23rd 2020

‘Pennsylvania Forced To Remove Hundreds Of Deaths From Coronavirus Death Count After Coroners Raise Red Flags‘ by Amanda Prestigiacomo, Daily Wire, April 25th 2020

‘Coronavirus deaths: how does Britain compare with other countries?‘ by David Spiegelhalter, The Guardian, April 30th 2020

‘Is the lockdown killing people?’ by Hector Drummond, Critic, May 1st 2020

‘The virus that turned up late‘ by Alastair Hames, Hector Drummond, May 9th 2020

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.