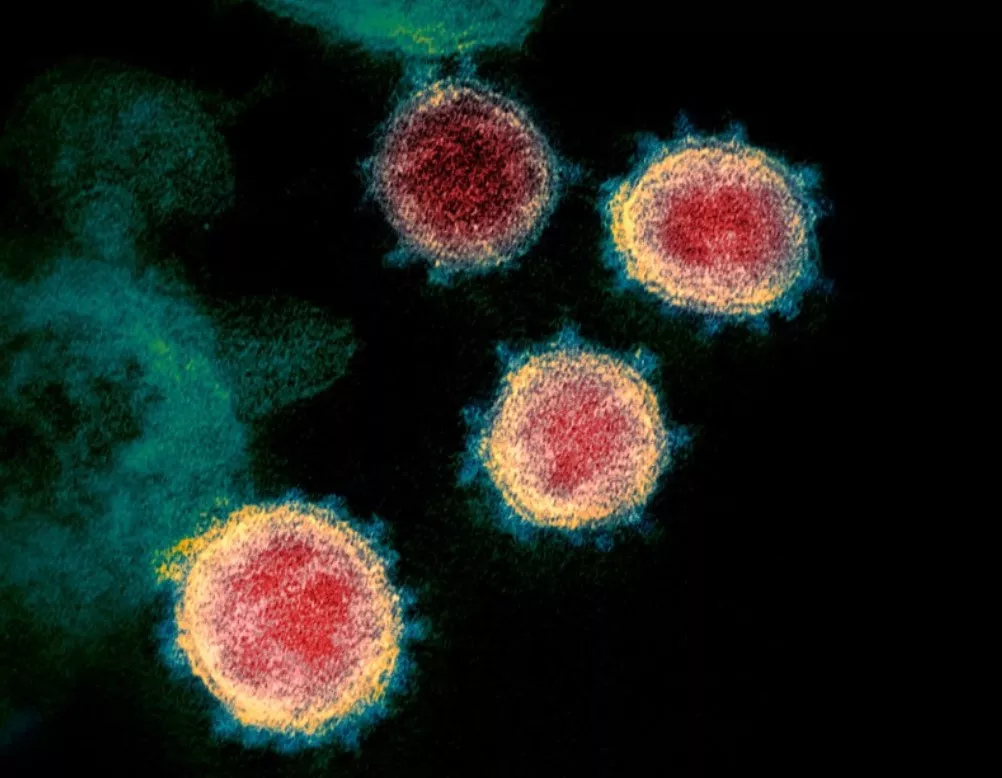

Researchers inoculated (exposed) 36 people aged 18-29 with SARS-CoV-2 (Wuhan strain) via nasal droplets in the first COVID-19 challenge trial. The dose was similar to that found in a droplet of nasal fluid (which seems on the high side compared to natural exposure – who inhales globules of snot?). What did they find?

First of all, two of the 36 were found to have developed antibodies between screening and inoculation, so although they were inoculated anyway they were excluded from most of the analysis (they didn’t develop an infection, unsurprisingly). That left 34. Of those, 18 (53%) tested PCR positive, 17 (50%) of them with symptoms and one without. This means 16 (47%) never tested positive, despite being heavily exposed via lying on their back for 10 minutes with a blob of infected snot up their nose. Why did they not get sick? The researchers say investigations of these questions are ongoing.

This raises an interesting question of what constitutes infection, as clearly all participants had been thoroughly exposed but for 16 of them their immune system dealt with it in some way without resulting in symptoms or PCR positivity. The proportion infected, 53%, is higher than the proportion of the population typically infected in an outbreak, such as on the Diamond Princess (where 19% tested PCR positive), but that may be owing to the level of exposure or other transmission dynamics.

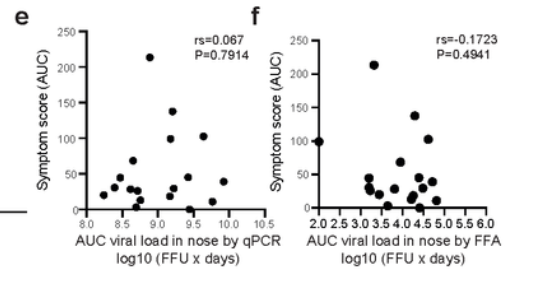

Interestingly, there was no correlation between symptom severity and viral load, measured both using Ct values from a PCR test and viable virus. Note the most symptomatic point in the charts below (the highest on the y-axis) does not have anywhere close to the highest viral load. Significantly, the one asymptomatic infection had no lower viral load or less viable virus than the symptomatic infections (the point sitting on the x-axis). This suggests that infectious asymptomatic infection may be a real phenomenon (though note this study did not test to see whether participants actually infected others).

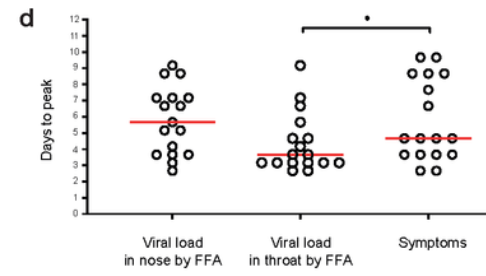

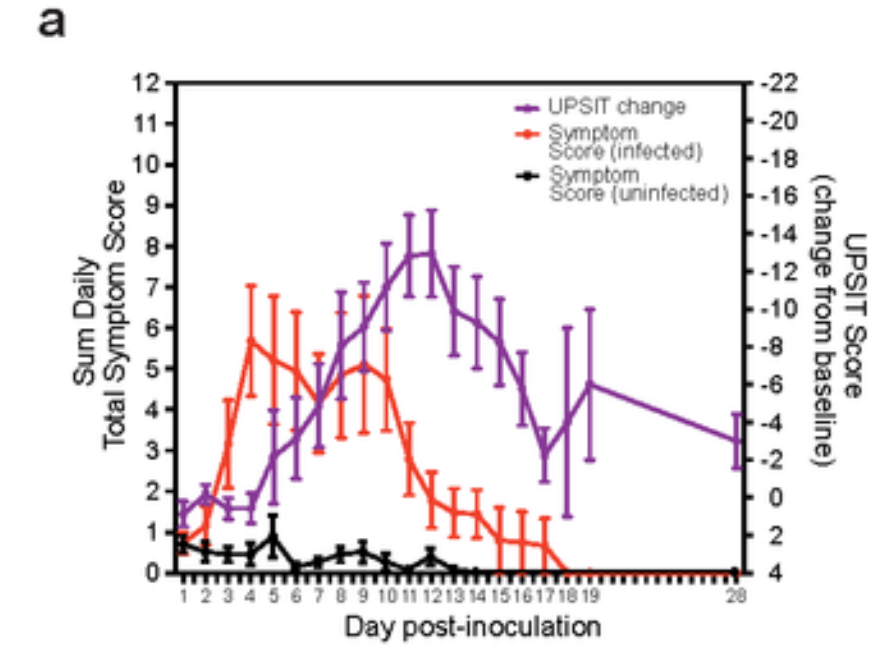

Viral load in the throat peaked on average around day three, a day earlier than the average peak of symptom severity on day four, itself a day earlier than the average peak of viral load in the nose (though the average peak viral load in the nose was higher).

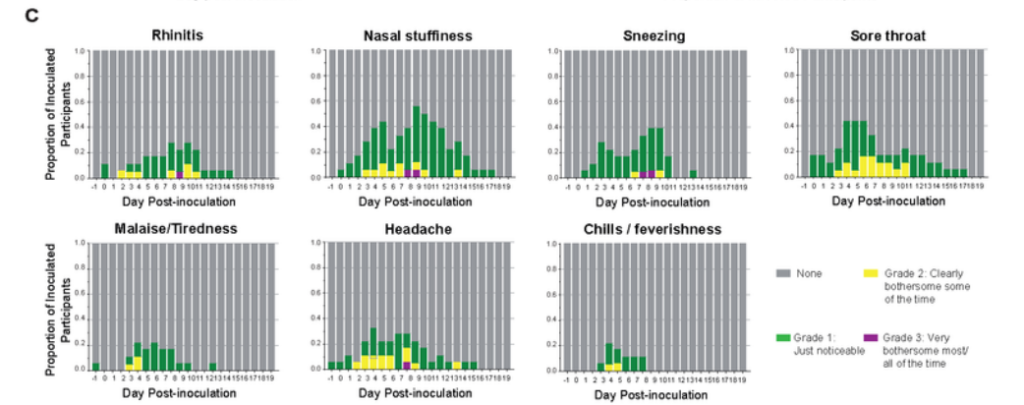

Symptom onset was often earlier, from day two, as can be seen in the charts below. No average value was given for symptom onset; however, the early symptom onset in many cases challenges the common idea that viral load peaks prior to symptom onset and drives pre-symptomatic transmission. That said, the early symptoms here tend to be mild. There are also questions as to how generalisable the results are to a natural infective dose, which is likely much lower.

The participants were tested with a PCR test every 12 hours, and also with LFTs daily. The results from the LFTs found that an LFT went positive on average (median) on day four, one to two days after the PCR test went positive and one day after viable virus was detectable. The researchers report that LFTs “mainly” went negative two to four days after viable virus detection had ceased. This suggests LFTs tend to miss the early infectious period by a day and miss the end of the infectious period by two to four days. The researchers felt their results supported the use of LFTs for “interrupting transmission”, but that conclusion seems debatable.

The authors say they intend to do further challenge trials, including with vaccinated volunteers, to ascertain the difference that vaccines might make. However, since it is now generally thought that the chief value in vaccination is protection of the high risk from serious illness, it is unclear how a challenge trial, which uses only young healthy volunteers, can shed much light on this.

Read the full study (which is not yet peer-reviewed) here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

I asked this yesterday but if this virus is “so deadly” how can anyone be allowed to deliberately infect someone with it?

Yesterday’s HSA week 5 vaccine surveillance report covers weeks 1-4, it finds:

2,872,077 cases of which 2,027,798 (70.6%) were within the vaccinated population & 844,279 (29.4%) were in the unvaccinated population.

If we restrict this to the over 18’s the percentage of the vaccinated testing positive increases to 88.74%.

In terms of fatalities there were:

A total of 5,554 fatalities, 4,539 (81.72%) were of vaccinated people 1,015 (18.28%) were of unvaccinated people.

65.1% of the population are triple vaxxed.

Yes, the vaccines are now showing negative efficacy and that is not a good thing.

Obviously, these researchers should be put in prison. If they keep walking free, they might get the idea to test masks or other NPI’s. Or worse, allow the control group to remain unvaccinated after a vaccine trial!

I know! It’s tantamount to murder isn’t it? Look him in the eyes and tell him you’ve just squirted covid up someone’s nose!

Or if you test ‘positive’ being told to go and lock yourself away for x days and that should sort the problem out.

It is quite easy — you’ve just got to believe in several mutually incompatible facts at the same time. People these days find this easy, because they’re outsourced their logical faculties to the BBC.

Orwell called it doublethink. He hadn’t had his booster at that time.

Not bad, having your logic outsourced for only £170 per annum.

It is not so deadly, but to intentionally infect anyone with it seems to border on criminal activity in my book.

They were volunteers. In China, they’d probably have been unwilling prisoners.

This is genuinely interesting stuff. So many of our assumptions about disease and their spread have been challenged in the last 2 years.

It could be one of those moments that lead to scientific revolution, where the fundamental assumptions science had been labouring under are debunked and replaced.

I fear the scientific community may be as unprepared as ever to take advantage of such a moment, given how invested it is in the current paradigm and our new age of.censorship.

The legacy of this crisis could be a breakthrough in our understanding of the microbial world. More likely what we will be left with is more government powers to govern our lives and a population more fearful of each other.

Don’t think there will be any revolutions sadly. A tremendous amount was already known but we seem to have gone backwards.

I fear the scientific community is no longer definitively scientific. They seem to be mainly grant-whores.

“The proportion infected of 53% is higher than the proportion of the population typically infected in an outbreak, such as on the Diamond Princess (19%), but that may be owing to the level of exposure or other transmission dynamics.”

One (among many) of the most glaringly obvious reasons why the models used to whip up panic in March were utter nonsense, and should have been known to be such by any reasonably intelligent and informed person even back then.

The current preferred “exit lie” for the Guilty Men – that “we were right to lock down then but we know more now” is like the similar excuses used for those who pushed the war on Iraq – self serving rubbish.

Thumbs up for terrain theory.

The Rosenau Experiment, 1918-1919 | GG Archives (gjenvick.com)

“The experiment began with 100 volunteers from the Navy who had no history of influenza. Rosenau was the first to report on the experiments conducted at Gallops Island in November and December 1918. His first volunteers received first one strain and then several strains of Pfeiffer bacillus by spray and swab into their noses and throats and then into their eyes.

When that procedure failed to produce disease, others were inoculated with mixtures of other organisms isolated from the throats and noses of influenza patients. Next, some volunteers received injections of blood from influenza patients.”

Germ Theory vs Terrain Theory (odysee.com)

Dr Sam Baily.

Sam Bailey?

I have seen her videos and read extracts from her book and she is talking absolute rubbish just to sell her book (always on display in her videos) to the gullible.

It appears to be more profitable to be a quack than a real doctor these days as shown by her co-conspirator Tom Cowan an ex doctor who had to hand in his license due to malpractice.

https://www.acsh.org/news/2021/02/10/how-quacks-become-millionaires-5g-covid-doctor-will-sell-supplements-15336

Many of her claims are not supported by evidence and have been totally debunked by real scientists who have shown real evidence to debunk her claims.

She used to be a TV doctor from New Zealand who appears to have little understanding of modern virology. Recently she has been under investigation by the medical authorities of New Zealand.

Her wild claims have been debunked on this science website ……

https://blog.waikato.ac.nz/bioblog/2021/04/sam-bailey-on-isolating-viruses-and-why-she-is-wrong/

She has also been debunked here ……

https://integralworld.net/visser214.html

19th century Terrain Theory has been blown out of the water by modern virology.

There have been recent experiments with influenza virus showing the same thing as in the covid studies,remarkable many not infected or mild disease.The more information we get on covid the more like the influenza virus,just look at the rapid resistance to the Wuhan strain vaccine. It transmit the same way,masks useless,mutate almost the same amount.And we had pandemic influenza plans which were not used in the corona pandemic.

What we seem to have had for two years is de Pfeffel bacillus. By spray, swab and BBC broadcast.

Terrain theory vs germ theory. Apparently we still have much to learn.

19th century Terrain Theory has been blown out of the water by modern virology.

They’re all gonna need a scientific control group soon. Y’ know, people who haven’t been stabbed with the

unapprovedhurriedly-approved-on-an-emergency-basis drugs. I guess they could do worse than start with the list of subscribers to Daily Sceptic.They seem to not want to have a control group and are trying very hard to achieve this.

And even me as a non scientist can work that one out….message to Big Pharma CEOs ( and their criminal associates ) “You fule no one”

I was planning to do at least some elementary analysis but – as usual – these funny graphics with symbols no third party can reliably associate with the actual numbers rendered that impossible. Hence, I’ll restrict myself to the following statements about the symptom peak:

Assuming there’s a population of 17 entities experiencing a phenomenon, with more than 3/4 (76.5%) not experiencing it on the 4th day, 41.2% experencing it earlier and 35.3% experiencing it later (23.5% on the 4th), on average on the 4th day is a completely useless metric.

47.1% experienced the phenomenon on day 3 or 4. 52.9% not on day 3 or 4. This 3+4 cluster looks random and suggests that this population was way to small to derive useful results from it.

[All percentages rounded to one decimal place]

The mere thought of having someone else’s snot infected or otherwise up my nose… too early in the day for this!

Just make sure you wear your blue fabric mask and you’ll be okay.

I’ve been waiting for the results of a challenge trial for the past 2 years. You’d think this sort of thing would be important, but it appears that it was enough just to believe that covid was so super transmissible that simply wafting past an infected person in the street was enough for infection.

It appears that covid is similar to some other upper respiratory tract infections, in that it is difficult to get infected by direct challenge. Quite how infection occurs is unclear, but it isn’t as simple as direct exposure = disease.

As an aside I’d note that there might be no direct relationship between disease severity and viral load, but there is a relationship between disease severity and antibody titre — the higher the antibody level the worse the symptoms. Funny how it all works.

As an aside I’d note that there might be no direct relationship between disease severity and viral load,

Judging from the excerpt, there was no relation between measured viral load and (self-)reported severity of symptoms classified using vaguely defined criteria (noticable and bothersome). What that’s supposed to communicate is anybody’s guess.

PCR cycle thresholds seem like a very inaccurate measure of viral load.

Ultimately then, Covid the disease is defined less by the virus and more by a person’s physical state. The severity of the disease is determined by how your body reacts to an encounter with this virus (e.g., whether or not your mucosal immunity is in good enough shape to deal with it and, if not, whether your body requires a large or small quantity of antibodies to fight it).

In other words, covvie behaves just lime any other trifling infection.

Shhh….the Sheepie will lose faith in “Sir” Chris Whitty and will never find their way home!

Our healthcare system is about to experience a tsunami! Potential side effects of jabs include chronic inflammation, because the vaccine continuously stimulates the immune system to produce antibodies. Other concerns include the possible integration of plasmid DNA into the body’s host genome, resulting in mutations, problems with DNA replication, triggering of autoimmune responses, and activation of cancer-causing genes. Alternative COVID cures EXIST. Ivermectin is one of them. While Ivermectin is very effective curing COVID symptoms, it has also been shown to eliminate certain cancers. Do not get the poison jab. Get your Ivermectin today while you still can! https://ivmpharmacy.com

Good job they’re not going to bag all those unvaxxed medical sorts, then?

Those with a supposed high viral load (lateral flow test) were given Remdesivir. Perhaps no wonder then that they became ill and rather surprisingly those given this very dodgy drug have all survived, though the longer term outlook for their livers mav be another matter. Deliberately inducing a supposed illness in healthy people and treating it with a dangerous drug seems to be taking stupidity to another level.

isn’t this exactly what Dr Fauci recommenced for AIDS patients as well …where many actually died?

He also blocked ivermectin use.

Remdesivir nicknamed Run Death Is Near by USA nurses , according to Robert Kennedys book The Real Anthony Fauci

I see Neil M. Ferguson and Jonathan Van-Tam are on the list of authors, that adds a lot of credibility to it.

Just move it from the non-fiction section?

Strange , I have a neighbour who hardly socialises, who is tripple jabbed with a recent booster …she has just contracted “Omicron” Covid. She tells me how much worse it would have been if she hadn’t been jabbed………no comment.

She also has a long standing heart condition.

It is a comfort blanket for people who are confused by what they have been told about the vaccine, aka cognitive dissonance. I have heard a similar response from several people since he turn of the year, all of them vaccine devotees.

Me too – I know of a couple who before the vacine rollouts practically cut themselves off from the entire outside world – the only means of contact was via the phone but under no circumstances was anyone to visit them – everything was ordered in, everything was sanitized, they wore masks and gloves around the home … we didn’t hear from them for months and then we got a phone call from the husband who was beside himself in disbelief because they had both come down with mild cold-like symptoms and they had both tested positive for covid … they blamed the postman, the delivery drivers, the bin men … both got over the virus within a few days – probably had natural immunity too but still they went ahead and got triple jabbed – then both suffered the usual jab side effects … headaches, bodyaches and tiredness etc.

Incredible really.

A key point which has been lost in medical science over the last 70 years is that the same illnesses can proceed quite differently in different people.

This really started with the development of penicillin – the “magic bullet” which could cure all infections. That made everybody think that you just needed a single treatment to cure a specified illness. And led to our modern central diagnosis regime, where doctors no longer have experience with patients, but instead read the recommended medicine from a computer screen….

I read the study earlier today. It is garbage.

Small sample, no control group, unblinded and the so called symptoms are highly variable and could be caused by anything.

The emissions of other humans are not designed to be inserted en masse up a person’s nose. That could create exactly the same outcome irrespective of the virus, that has not been isolated.

Furthermore, given that the study was unblinded, the researchers no doubt strove to identify symptoms. We all get the odd cough or a headache.

I could go on but it would be great if Dr Tom Cowan or Dr Sam Bailey were to do a video on this garbage study. I am sure their insights would£ be more effective than mine.

The study is consistent though with a finding that nobody gets ill from the virus.

Even in more ‘intimate’ settings.

Sam Bailey? “Ex Dr” Tom Cowan?

I have seen her videos and read extracts from her book and she is talking absolute rubbish just to sell her book (always on display in her videos) to the gullible.

It appears to be more profitable to be a quack than a real doctor these days as shown by her co-conspirator Tom Cowan an ex doctor who had to hand in his license due to malpractice.

https://www.acsh.org/news/2021/02/10/how-quacks-become-millionaires-5g-covid-doctor-will-sell-supplements-15336

Many of her claims are not supported by evidence and have been totally debunked by real scientists who have shown real evidence to debunk her claims.

She used to be a TV doctor from New Zealand who appears to have little understanding of modern virology. Recently she has been under investigation by the medical authorities of New Zealand.

Her wild claims have been debunked on this science website ……

https://blog.waikato.ac.nz/bioblog/2021/04/sam-bailey-on-isolating-viruses-and-why-she-is-wrong/

She has also been debunked here ……

https://integralworld.net/visser214.html

Crikey astonishing. There is a virus around, whether you get ill depends on whether you are healthy or not. Give them all a gold clock!

Vaccines are different than what’s being pushed now

Hello! I want to know, is there anyone else out there feeling like me? Is there anyone else in a similar situation?

I live abroad, away from the country where I have citizenship and spent most of my life. I haven’t seen parents or sisters for over three years.

At the same time, I’ve been becoming increasingly alienated from them.

They’re all onboard with the covid hysteria, whereas I committed to looking into what was going on from the get go. And we are now continents apart both literally and figuratively.

A few days ago, I had a right proper dust up with my moth, one which I don’t feel proud of. In fact, I feel ashamed. But I’m also feeling at the end of my rope.

Today, I made the mistake of going onto Facebook, to see this shocking and disgusting picture that my sister had posted about my beloved niece.

I’m feeling at my wits end with all this and realize my family basically isn’t my family anymore.

For over 20 years I have despaired of humanity, as I watched the Climate Change fraud develop with any opposition sidelined, suppressed and cancelled.

I no longer want to be associated with the human race.

Two thoughts, a study with less than 100 participants is not normally accepted by the greater scientific community.

Why when so many frail elderly DIED post vaxx, in all our nursing homes, does anyone believe the MOST vulnerable should be at the front of the queue for a death shot?

immune erosion? That is what the Israeli health minister is now calling the situation in Israel, whereby people are dropping like flies after their fourth jab. He admits, they made a “mistake”.

I hadn’t noticed the Israeli thing until you mentioned it. Wow!

It would have helped if the article had mentioned that the ‘healthy’ volunteers were aged between 18 and 29, since that’s the first question that came to my mind.

A shame, really, that the study didn’t have a wider age spread, since 50% of young, fit people being able to fight off a virus is not earth-shaking news.

Right, now, when are they doing the one that proves masks are basically useless? That one is of utmost importance now.

I remember reading a paper in 2020 that said that ingestion was the biggest route of transmission in flu, ie touching something infected then touching your mouth, nose or food and eating etc, rather than the airbourne route. Hence why at the start they encouraged handwashing etc. I was therefore unsurprised that the more transmissible omicron has more classic cold symptoms like runny nose, sneezing, sore throat. Considering we know the biggest sources of spread are hospitals and care homes where nurses are touching patients and food and their masks and pretty much everything else in the hospital. It makes sense to me.

Regarding asymptomatic transmission, surely it is pretty much irrelevant as to the viral load as the mechanism of spread is not there. yes a very low % might be in theory able to pass it on by some means, but the vast majority simply dont have the mechanism of transfer, be it runny nose or sneeze or cough. The notion that you are breathing out virus in sufficient quantity to infect someone is nonsense. Lets say you breathe in virus, what happens for it to infect you – it gets stuck to generally your urt where there is mucosal protection. It wouldnt exist very long as a virus if in the next breath out it went again. Any replicated virus is also in this same environment so unless there is the kinetic energy to remove the virus from the area, which normal breathing doesnt provide, it aint going anywhere in sufficient quantity. Your body will usually react to get rid of the virus by coughing, sneezing, runny nose and thats how its transmitted. asymtomatic people can be ignored. All that was ever needed was basic infection control measures that have been around for decades, but done properly

One might think the next thing to do might be to examine everything they can about the test subjects and establish the any and all commonalities between the group that avoided infection completely.

Did anyone else notice that there were no control group of participants who did not receive inoculation of the manufactured (and in my opinion questionable) ‘virus isolate’, or placebo? Any results from such a study are completely unscientific and should certainly not be published in a national newspaper (especially being not peer reviewed).

Some people get colds because they believe going outside in the cold with wet hair will give you a cold! I think that believing a virus was squirted up the nose even if in reality it was a placebo, might just manifest as a symptomatic reaction!