The following is the text of a speech I gave at the Margaret Thatcher Centre Freedom Festival yesterday.

Since arriving in the House of Lords, the most disheartening thing is how often a Government Minister is able to reply to an excellent point made by a member of the Opposition by saying: “But the noble lord will recall that this was the policy of his own government.” I’m thinking of the Football Governance Bill, in particular, but there are dozens of other examples. Turns out, the Conservative Party didn’t do anything particularly conservative in the years 2010 to 2024. True, there were some exceptions – education reform, Brexit, the occasional good person elevated to the House of Lords. But not many.

So my subject today is why do Conservatives abandon their principles in office? Why did Margaret Thatcher’s ministries turn out to be the exception and not the rule?

I thought I’d take as my case study the decision of Boris Johnson’s Government to tell everyone to remain in their homes on March 23rd 2020, five years ago tomorrow.

As Lord Sumption pointed out, the lockdown is the greatest interference in personal liberty in the history of these islands, yet it was imposed on the country by probably the most freedom-loving Conservative government we’d had since Margaret Thatcher’s last administration, led by a libertarian conservative and with a majority of 80.

Now, many people here no doubt supported the decision to lockdown five years ago and, even if you think now, with the benefit of hindsight, it caused more harm that it prevented, you may still believe the government at the time had no choice, given limited information in the face of a terrifying, existential risk. Michael Gove, who was one of the key decision-makers in March 2020, made this point eloquently in the discussion we had about the first lockdown at the Spectator last week.

I disagree obviously. I was one of a tiny handful of journalists to oppose the first lockdown – and I’d like to briefly remind you of the case for not locking down at the time.

First, the Government had a carefully worked out strategy in place to deal with the outbreak of a respiratory virus, distilling the lessons learned from how we’d reacted to previous pandemics and epidemics, in the hope that they wouldn’t repeat those mistakes. It was called the Pandemic Preparedness Strategy and among the critical pieces of advice it contained were: in the event of a viral outbreak, do not quarantine the healthy as well as the sick; do not force non-essential businesses to shut down; do not close schools. Unfortunately, it was disregarded almost immediately – consigned to the circular file – binned.

Some will be quick to point out that I’ve left out a crucial word. In fact, it was called the Influenza Pandemic Preparedness Strategy and this wasn’t an outbreak of influenza.

But that’s a poor excuse. The authors of the strategy made it clear that in the event of a SARS-like viral outbreak, the plan was adaptable. It actually said: this plan can be “adapted and deployed for scenarios such as an outbreak of another infectious disease, e.g. SARS”.

Happily for those scientists and officials who developed this strategy, not to mention the tens of millions of pounds that paid for public inquiries into earlier viral outbreak, it wasn’t a complete waste of taxpayers’ money. A Swedish Pandemic Preparedness Strategy, along similar lines to ours, was enthusiastically put into action by Anders Tegnell, Sweden’s Chief Epidemiologist.

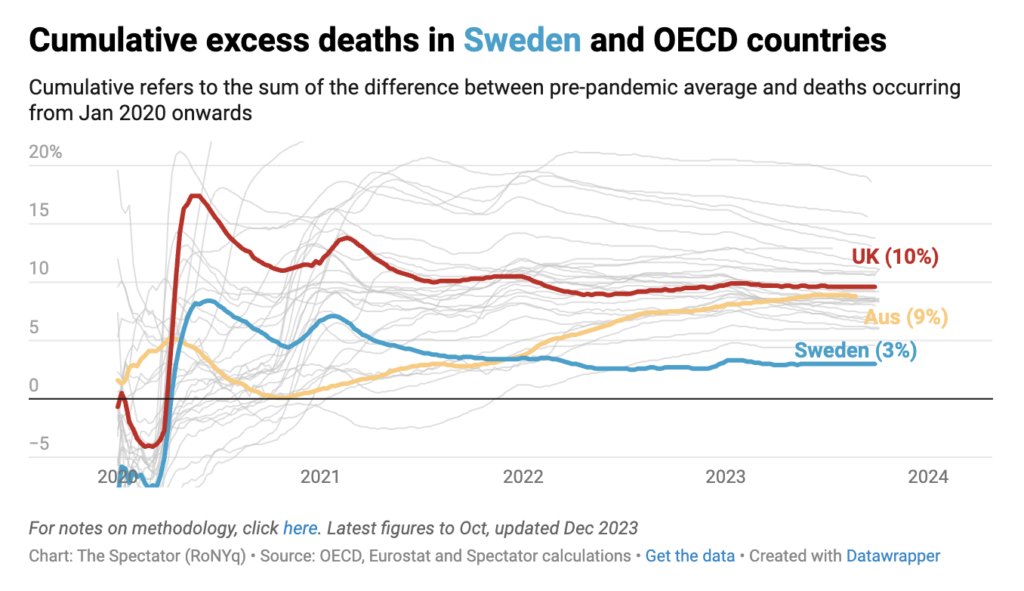

As you are no doubt aware, Sweden did not impose any lockdowns in 2020 and experienced one of the lowest, if not the lowest, rate of excess deaths in the OECD in the years 2020-22.

Some will say Sweden is not like the UK, but in fact 88% of Swedes live in urban areas, compared to just 84% of the population of the UK. And Stockholm is no less densely populated than cities in the UK.

So why did our Government abandon this strategy? One reason is ministers were panicked by a paper produced by Professor Neil Ferguson, a physicist-turned-epidemiologist from Imperial College and a member of SAGE, which predicted that if the UK didn’t lock down, 510,000 people would die from COVID-19 in the course of the next few months.

SAGE duly digested this paper and described Ferguson’s prediction as a “reasonable worse case” scenario.

Now, you might think: what Government wouldn’t have locked down if the deaths of 510,000 people was a “reasonable worst case” scenario if it didn’t?

Needless to say, a ‘reasonable worse case’ isn’t something with a high likelihood of occurring, one reason the Government hadn’t troubled itself to carry out a cost-benefit analysis of ‘lockdown’ before the pandemic hit.

An article in the FT in July 2020 included interviews with some of the people involved in the decision to lock down at the Cobra meeting on March 20th 2020, where each of the leaders of the different nations that make up the UK decided to collectively endorse a UK-wide lockdown, and Jesse Norman said he was the only person to ask whether a cost-benefit analysis had been done. Michael Gove, who was chairing the meeting in Boris Johnson’s place, gave him a look of mild astonishment, shocked that anyone could be so naïve as to ask that question.

In Michael’s defence, he could have argued that a cost-benefit analysis might well have shown that, in all likelihood, the harm caused by locking down would be greater than any harm it prevented. After all, the chances of 510,000 people dying from COVID-19 over the next year if they didn’t lock down was not high. And we have good reason to believe that had our Government not locked down, 510,000 people would not have died from the virus. Ferguson’s model predicted 85,000 Swedes would die over the course of a few months if Sweden didn’t lock down. In fact, the death toll from the virus in Sweden by the end of August 2020 was 5,800, with half of those deaths in care homes who would likely have died even if Anders Tegnell had recommended a lockdown.

Nevertheless, Michael might have said, if there is a risk of a catastrophic scenario materialising, it is the duty of a responsible Government to do everything it can to mitigate that risk. Risk aversion is not irrational. We all wear seatbelts, after all.

But how likely is a ‘worse case scenario’ to materialise? We know from Ferguson’s previous work that he had a tendency to exaggerate the deaths likely to be caused by a viral outbreak. The most famous example is the bird flu pandemic of 2005, which Ferguson said could kill up to 200 million people worldwide. In fact, it killed 74.

Scientists and mathematicians involved in disease modelling are reluctant to define what they mean by a ‘reasonable worse case’ scenario, but the UK National Risk Register defines it as the “worst plausible manifestation of that particular risk”. In 2017, the same register defined “plausible” as having “at least a one in 20,000 chance of occurring in the UK in the next five years”. If my maths is correct, that would mean a worse case scenario has a one in 100,000 risk of occurring in a particular year.

So, to extrapolate, if we treat Neil Ferguson’s prediction as a ‘reasonable worse case’ scenario, which is how it was described by Sage, that means the chances of 510,000 people dying from COVID-19 over the course of the next few months in the event of the government doing nothing were one in 100,000.

I would accept that if there was a 10% chance of 510,000 people dying if the government didn’t lockdown, locking down in March 2020 might have been a responsible thing to do – even a one in 20 risk. But one in 100,000?

What makes this so hard to understand is that the harm caused by the lockdown was entirely foreseeable. When the government did get around to publishing a cost-benefit analysis on April 8th 2020, two weeks after the horse had bolted, it estimated that a 75% reduction in non-emergency healthcare alone would result in 185,000 deaths.

A second report published on July 15th revised this 185,000 figure down on the optimistic assumption that treatment would be postponed rather than cancelled because the NHS would find the capacity to work through the backlog post-lockdown and catch up.

Last time I checked, the NHS waiting list was 7.5 million.

Some will say, “Well, maybe the risk of people dying from the virus was exaggerated, but what about the risk of ‘our’ NHS being overwhelmed? Surely that was higher than one in 100,000?”

I would accept that it was higher than that – considerably higher. After all, intensive care capacity in Lombardy did reach saturation point in early March 2020, although predictions of how long that would remain the case were exaggerated. But how high?

Once again, we turn to the Swedish example: in spite of not locking down, health services in Sweden were not overwhelmed.

Another thing to bear in mind is that the rate of infection was actually falling by the third week of March in 2020. Chris Whitty, then the Chief Medical Officer of England and the Government’s Chief Medical Advisor, admitted as much under questioning by the Health Select Committee in July 2020. He said the coronavirus pandemic was probably already in retreat before the full lockdown was imposed on March 23rd 2020, i.e., the R rate was below one.

Nevertheless, true blue, freedom-loving conservatives, the sort of people we would have wanted to be in charge in the event of a viral outbreak, decided to lock everyone in their homes almost exactly five years ago. They prioritised safety over liberty. They were responsible for the greatest interference in personal liberty in the history of these islands to avert a one in 100,000 risk of 510,000 people dying.

So, why did they prove so spineless? I should point out that it wasn’t just conservative politicians, but lots of conservative journalists, too, who heartily endorsed the lockdown. Even people in Right-wing conservative think tanks, people on our wing of the movement – members of our tribe! – became lockdown enthusiasts. At the time, I called them ‘Libertarians for lockdown’. I won’t name names because I’m still friends with some of them and in most other policy areas we are still comrades-in-arms.

But why did so many people in this movement – our movement – embrace this catastrophic policy?

I can think of three reasons.

First, I think it was a yearning for the approval of the metropolitan liberal intelligentsia. Being at odds with the BBC, most national newspapers, the Civil Service, the majority of the political class, the Great and the Good, etc, in almost every public debate isn’t as much fun as it sounds. Being cast as evil Tories, as not caring about the poor and the dispossessed, of putting profit before people, of shilling for the oil and gas industry – it takes its psychological toll. With the pandemic, here was an opportunity at last to be on the same side as the chattering classes, to bask in their approval. “See! We’re not as evil as you think. We don’t want to kill granny either.”

I fear that for many of our friends, that opportunity was irresistible.

Second, I think doing nothing in the event of a national crisis – Neil Ferguson literally described the scenario in which 510,000 people would die as the “do nothing” scenario – is extremely difficult for politicians and policy wonks, however committed they are to small-state conservatism. After all, what is the point of them if their years of toiling in the think tank mines means all they can recommend is that we ‘do nothing’ during the biggest national crisis of our lifetime? Doing something – anything – that will enable them to show off their policy chops is infinitely more appealing.

Finally, I think the reason Cabinet Ministers abandoned their commitment to liberty is because, in the words of the other Lord Acton, power tends to corrupt. Imagine, if you will, how soul destroying it is to be a politician in the normal course of events. You finally arrive at the top of the tree after years of soul-destroying grunt work as a party hack and discover that – you’re essentially powerless. You pull the levers and nothing happens.

I remember when my children were younger having a fake steering wheel that we would attach to the back seat with a suction pad. As I was driving along, a child in the backseat would gurgle with pleasure as he yanked the toy wheel this way and that, imagining he was steering the car. That’s what it’s like being a minister of state. After a while, it becomes obvious that you’re the toddler in the back seat – someone else is driving the car. And that must be frustrating.

But here, at last, was an opportunity to grab the steering wheel and put yourself in charge. Suddenly, the decisions you are taking – “You must stay in your homes”, “You must keep two metres between you and the person next to you at all times”, “You cannot drink alcohol in a pub unless you’re having a substantial meal”, “A scotch egg is not a substantial meal” – have real world consequences. When you dreamt about one day having power, this is what you fantasised about. Advisors hanging on your every word. Officials running and dashing. The police arresting people for disobeying your edicts. Again, the opportunity to finally exercise power – to ‘make a difference’ – was irresistible.

So what’s the lesson here? I’m reluctant to draw any conclusions because, as we saw with the Pandemic Preparedness Strategy, lessons aren’t learned – they’re abandoned the moment it becomes politically expedient to do so. But if there’s one lesson here I hope that at least those in this room can take to heart it is that if, God willing, you ever find yourself in power, or in a position of influence, you remember that sometimes the wisest thing to do is to do nothing.

I am grateful for the help of Will Jones and Clare Craig when preparing this speech.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.