It’s well known that some countries and jurisdictions offer very low tax rates for wealthy individuals or multinational corporations. But how much impact do they have in terms of global profit-shifting? And who are the biggest losers?

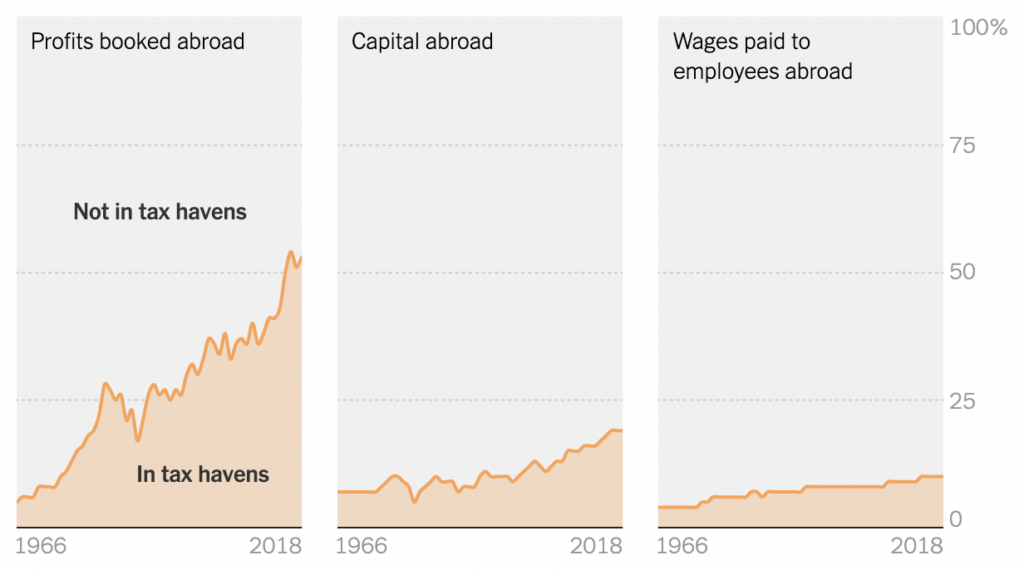

According to economist Gabriel Zucman, a leading researcher in this area, use of tax havens has grown substantially over the last half century. The graphic below shows trends for US multinationals.

The left-hand chart indicates that companies have been reporting an increasing share of their overseas profits in tax havens – rising to more than half in 2018. Meanwhile, the share of their capital and wages allocated to tax havens has only risen slightly – as seen in the other two charts. This is essentially a smoking gun for profit-shifting. Companies are recording more and more of their profits in tax havens without doing much more actual business there.

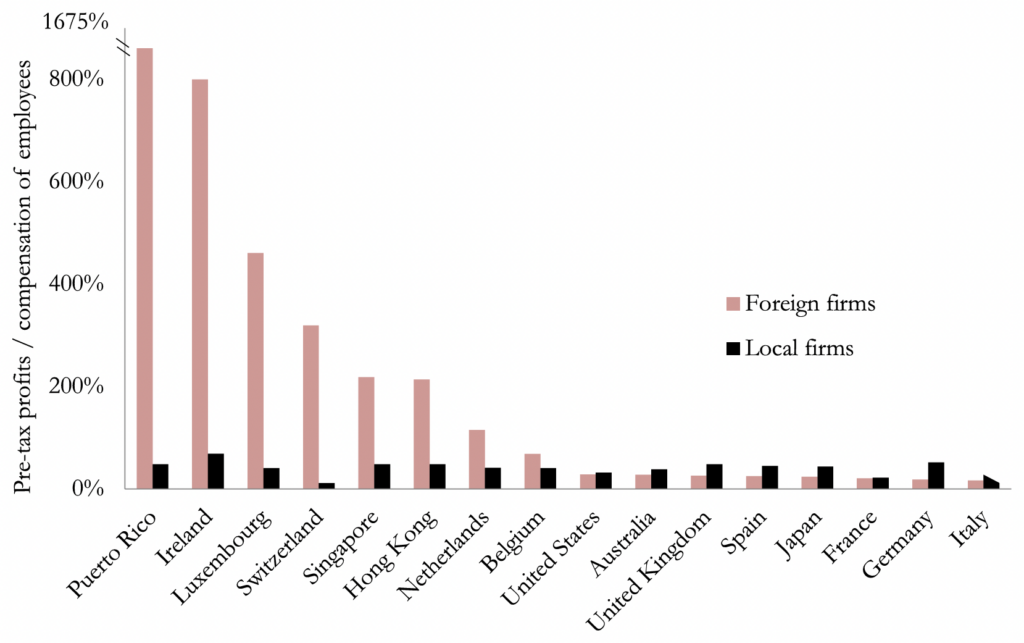

So where are the biggest tax havens? Different researchers have compiled their own lists of the ‘top 10’, but they turn out to be more or less identical, with the same countries cropping up again and again: Ireland, Switzerland, Luxembourg, Puerto Rico, Singapore etc. Yes, the Celtic Tiger is now among the world’s biggest tax havens.

The chart below, taken from a paper by Zucman, shows the ratio of profits to wages for foreign and domestic firms in various countries around the world. For large Western countries like the UK and France, the two bars are roughly equal in height: foreign firms are about as profitable as domestic firms. But for the jurisdictions mentioned above, foreign firms are vastly more profitable. This, again, is unmistakable evidence of profit shifting.

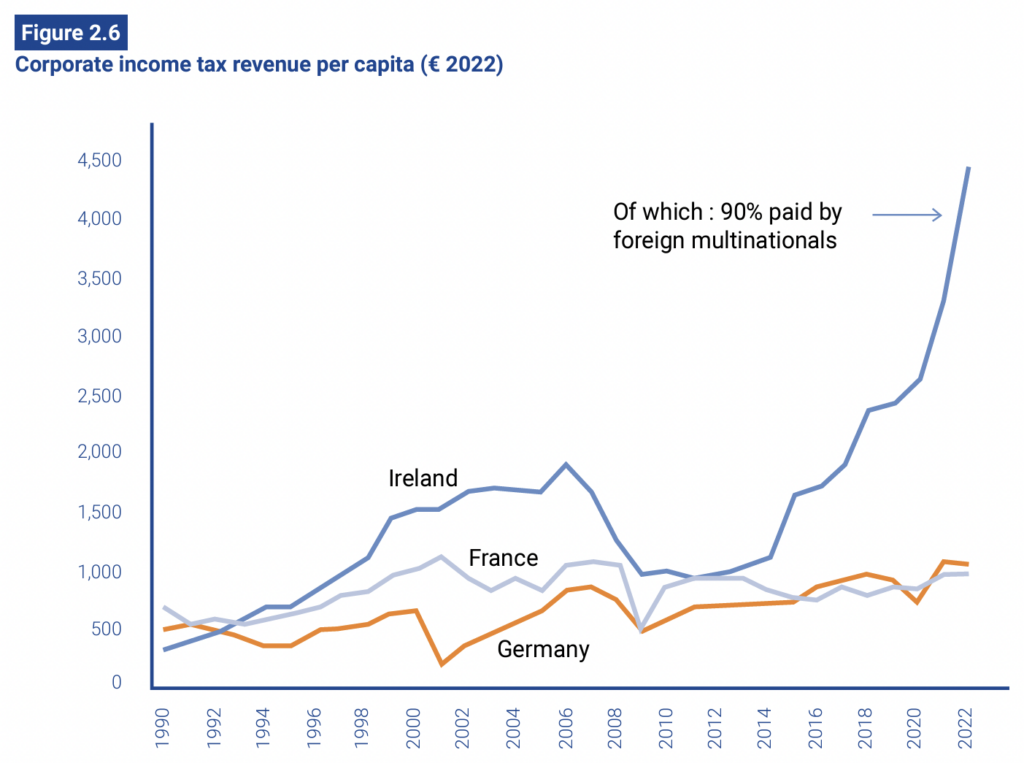

A major consequence is that those few jurisdictions collect vastly more tax revenue than they otherwise would. The next chart shows corporation tax revenue per capita in Ireland, France and Germany from 1990 to 2022. Since Ireland ‘reorganised its affairs’ in the early 2010s, there’s been a huge divergence, and the country now collects more than four times more corporation tax revenue per capita than France or Germany.

Zucman and his colleagues estimate that 36% of multinationals’ profits were shifted to tax havens in 2015 – the latest year for which data were available. And where were these profits shifted from? Who, in other words, are the biggest losers? In short, it’s high-tax European countries like the UK. According to Zucman and his colleagues, Britain’s corporation tax revenues are 18% lower than they would be in the absence of profit shifting.

Now, this profit shifting is basically a zero-sum game. Places like Ireland are essentially stealing tax revenue from their neighbours. Productive activity that generates profits takes place in the UK, France or Germany, and then the profits get taxed in Ireland. The Irish government ends up with more money to spend on public services, while those other countries have less.

Why don’t those other countries put a stop to this by applying some pressure? The answer is not entirely clear. One possibility is that elites within losing countries have an interest in the continued existence of tax havens, since they’re more likely to be shareholders in multinational corporations, and/or the corporations themselves lobby governments not to take action.

Another possibility is that it’s an arms race: as soon as you close one loophole, another one opens up. While this may be true to an extent, it has a hard time explaining how places like Luxembourg and Switzerland have managed to remain tax havens for decades without much being done.

What is clear is that tax havens’ impact is far from trivial. Major European governments are losing billions of dollars in revenue to them every year, and will continue losing revenue unless they take action.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Some terrible stories. It just adds to my disrespect for the police and judiciary.

Nobody who had not lived through the past 25-30 years of British politics could imagine any of this. Each of the three reports describe disgraceful public services and suffering by the people.

Past monarchs have been displaced and killed for less.

if the current situation persists we will be in for a tough time. More likely it will get worse. The implications of it getting worse may result in a government very different from anything we have known and it might not be pleasant.

I am not confident of outliving this terror.

We quite literally live in a police state.

I wish I could say I am shocked or surprised but I cannot. But if Starmer and his gang think they can get away with this they have another think coming. And I hold the Tories and LibDems equally responsible because they been quietly or not so quietly acquiescent in the loss of our freedoms over the last 25/30 years, most particularly freedom of speech. Contrary to the will of most of the electorate.

The real problems for the government will come in the new year when cold weather will inevitably lead to power cuts and the trial of the Southport killer will lead to some interesting revelations. This is a one term government and better still the last Labour government ever to be elected.