Join me for a moment as I engage, Nostradamus-like, in acts of prognostication.

Let us begin with a simple thought experiment. Imagine somebody were to put a gun to your head and ask you to say which you thought was the more likely of the following two scenarios:

- In the year 2124, nobody will be reading text on physical paper

- In the year 2124, nobody will be reading text on digital media

Imagine this choice was also caveated by the proviso that in 2124 human beings will still exist and that they will still need to read text; we don’t all get wiped out by a meteor strike in 2058, or lobotomised and enslaved by space aliens in 2026, or merged with the singularity in 2123 etc.

Next, I want you to imagine that this person has in his possession a crystal ball that will shortly reveal to him what 2124 actually looks like, and that he is going to blow your brains out if you choose one scenario or the other and it turns out the alternative was in fact true. If you said you thought that in 2124 nobody will be reading text on digital media, and the crystal ball informs the gunman that actually nobody will be reading text on physical paper (or vice versa), he will pull the trigger. In other words, you have to stake your life on a choice about which of the two scenarios presented above is more certain to be false. What would you say?

The question, obviously, is based on an incomplete premise. Neither of those scenarios sounds very likely – the real-world in 2124 will presumably be somewhere in the middle of those two extremes, and you might indeed consider it quite likely that we will merge with the singularity, or at least reach a point where we can simply download information directly into our brains (not to mention being conquered by invaders from another galaxy) within that timeframe. Whichever choice you make, it seems unlikely that it will actually end in death.

But the thought experiment is still an interesting one to perform, because it elucidates something important about the way in which we think about the future. Instinctively, almost all of us have an intuition that it is more likely that we will have abandoned physical paper entirely by 2124 than that we will have abandoned digital media. And this, in itself, reveals us to be thoroughly and almost irredeemably modern: we believe in progress, understood in a particular way – and occupying a particular trajectory. We feel as though we know the direction in which we are going (whether we like that direction or not), and we think we are going to go that way more or less forever from here on in.

Well, I would like to go out on a limb in this post and explain why it is that I think, of the two scenarios provided to us by our prophetic gunman, the more preposterous of the two is actually the first. I think the world of the physical, the tangible, the substantive, the grounded, is going to return to prominence – and in a big way. And I do not think the kind of digital dominance that we currently experience and which is no doubt accelerating will, in the grand scheme of things, survive for very long. In short, I do not believe in progress of the type which we intuit to be true – and I will even stick my neck out and say that I do not believe in the project of modernity at all. Bear with me, then, while I explain.

Modernity’s Future Trajectory

During this substack’s existence I have made the case (I am far from being the only person to have done so) that we can understand modernity as the obliteration of theological justifications for anything. If there is one thing that moderns cannot and will not accept, it is the justification: “Because God says so.”

The immediate result of this, of course, is that modernity recognises no principled basis why any phenomenon should not be subject to interrogation and critique; ostensibly anything can be brought before “the tribunal of the intellect” (an Oakeshottism that I have used before) and forced to defend itself. And the next-most immediate result is, therefore, that anything and everything must be able to justify itself in terms which moderns will accept. The state, the political economy, the nation, the church, the family, marriage, the distinction between adults and children, the distinction between humans and animals, love, parenthood, our relationship to nature, even the very existence of humanity itself – none of these things can appeal to God, or natural right, in order to secure their position. None of them can have a deontological reason for being the way they are. Instead, all must have a thoroughgoing consequentialist basis for their ongoing existence and must continue to provide their justification in those terms against unrelenting intellectual assault.

To put this more succinctly, under modernity’s reign, no institution, norm or state of affairs may be permitted to exist which cannot be satisfactorily proven at any given moment to make life ‘better’ in purely consequentialist terms.

Another, related result is that modernity is – to use another favourite phrase that I have used before – ‘individualising and totalising’. Since the existence of anything to which anybody might display loyalty (family, church, nation, etc.) is up for grabs, it is always to the modern person persuasive that such loyalties should only be displayed where they can be justified – and hence that they can be jettisoned on the same terms. We are loyal to institutions only as long as there is something in it for us. This is true both individually and at the societal level, as we can see in, for instance, our individual commitments to our own marriages, and our societal commitments to the institution of marriage as such.

This has the effect, naturally, of breaking down such loyalties, and indeed atomising us to the degree that our only loyalties tend to be towards ourselves. But it also has the effect – counterintuitively – of cementing our loyalty to the state, understood as a continuous practice of reflexive government which is always and everywhere engaged vigorously in the exercise of justifying itself through the act of governing. It is the state, and the state alone, which is able to say to moderns: “I am always justified, because it is I who governs, and without government things will be worse.” The state always has a plausible consequentialist account for its existence, and so it is the only institution whose existence is not questioned, and which therefore becomes the depository of all individual loyalties.

And this has a further effect, which I have also alluded to in recent posts: the lionisation of substantive equality, and indeed of DEI/EDI, as our overriding obsession. Modernity, as I have here described it, is an individuating force which produces in the heart of each of us the sense that we should assess anything and everything in terms of what is better, consequentially, for the self and the self alone. We want things to be better for ‘us’ as individuals to the exclusion of all other considerations. And in aggregate, a society that comprises a mass of individuals who all only want things to be better individually for themselves is collectively one which cannot tolerate distinctions in outcome – one which, indeed, can in the end tolerate nothing other than perfect substantive equality: all of us moving forward, but only in total lock-step.

The sum total of all of these trends is that modernity is characterised by a centripetal force which ruthlessly and remorselessly centralises. It destroys borders, rules, norms and institutions; it encourages circulation and flow; it seeks paradoxically to both improve and equalise; it brings everything together by remorseless logic to what one is compelled to agree is properly called a ‘singularity’.

The only thing to add is that it also – for want of a better word – ‘technologises’; in fact, it venerates technology and technological advancement, since such advancement is definitionally able to prove itself to be in consequentialist terms making things ‘better’ (and may indeed be the only thing which can do so). If modernity is characterised by nothing else, indeed, it is characterised by the lack of any principled objection to technological advancement – there is simply no basis on which moderns can place any limits on the directions in which technology can go, for all that they may have misgivings in theory.

That is how I would define modernity (though I have elsewhere described it as the position of “lacking a principled argument as to why the state should not tell you what underwear you are allowed to wear”), and this, I think you can probably see, is the road on which we are travelling. It has taken a long time to get to the position in which we find ourselves, beginning with Machiavelli and his sparring partners 500 or so years ago, but we are now far advanced on that journey – having indeed reached a point at which most ordinary people, if pressed, can say basically nothing in defence of the existence of the most basic of institutions (the family, national borders, sexual morality, etc.) at all, and have become so unmoored from a concept of natural right that they find it difficult to explain why, for example, children should not be taught about masturbation in primary school, secure borders are important, people should not be permitted to self-mutilate, and so on and so forth.

Modernity’s Doom

In light of this, one might be tempted to say that it seems very likely indeed that we are heading towards a future of total digitisation – or, indeed, the ‘singularity’ as it is popularly understood. This would in fact be the culmination of modernity itself: the complete integration of an atomised, deracinated humanity into a perfect technocracy, deployed through the fusion of technology and the state itself. But, as you will recall, I framed the foregoing account with a declaration: I do not believe in modernity’s project, and I think it is doomed to fail. That future will never emerge. And this is for four sets of reasons, which I will call the practical, structural, biological and spiritual.

Practical reasons first. There is a strange idea that floats about in the heady atmosphere of online ‘dissident Right’ circles, to the effect that our contemporary obsession with diversity is producing a ‘competence crisis’, because at the margins it prioritises inclusion over meritocracy with the effect that complex systems are falling apart. I have a future post brewing about why these people have become so unmoored from reality that they find this account plausible, but to summarise my argument briefly: modern government’s predominant feature is the drive to make the population rely upon it; it can justify its existence on no other grounds than that the population needs it. Everything that the modern state does can be understood in those terms. This necessarily means that as modernity progresses, the state increasingly undermines the tendencies towards self-reliance and autonomy that exist within the population, and so the population in general becomes more enervated, passive, pliant, servile, dependent, and – yes – incompetent.

This is why everywhere your look in the developed world you see the same basic dynamic emerging: the pool of productive, useful, capable people diminishing (or being supplemented by a boost in immigration that can only realistically last for a relatively short period of time), and the pool of unproductive, state-subsidised people – both welfare recipients and middle-class holders of ‘bullshit’ WFH sinecures – swelling to the point of overflowing. This is not, to coin a phrase, sustainable, although fiat money and inertia will keep it going for some time yet. It has nothing really to do with a recent, diversity-fuelled ‘competence crisis’; it is the result of developments which go a tiny bit deeper and further back, than that.

Structural reasons second. Modernity, which, as we have seen, centralises, also by definition fragilises: it produces single points of failure – or, if you prefer the homelier metaphor, puts all of the eggs of society in one basket. The more power is concentrated in the state, and the more that alternative sources of loyalty disappear, the more that civilisation becomes vulnerable to true catastrophe; a foolish or incompetent government is tolerable if it has little to do, but may bring a nation to its knees if it is the only game in town.

It is not, then, exactly that modernity produces bad government (though indeed it does, for reasons we can come back to another day), but rather that it exposes us to what one might call ‘tail risks’ – the governing class may not go collectively bonkers or become ideologically corrupt, but if it does, then the fact that power is centralised in its hands will make matters far worse than they would otherwise be. Modernity despises the kind of redundancy that nature understands; as Nassim Taleb once memorably put it, nature gives us all two kidneys in case one fails – modern reasoning in principle would rather we just have one great big state-owned kidney which we all plug into once a day for dialysis, on the basis of its greater ‘efficiency’. That kind of imperative can be seen everywhere, from the way in which government is centralised at the expense of local and regional decision-making to the way in which policy on important issues – climate change, migration, development, trade, biosecurity, etc. – is determined almost universally within international fora, such that there are no meaningful distinctions between states at all. This is another thing which is not – to repeat – sustainable.

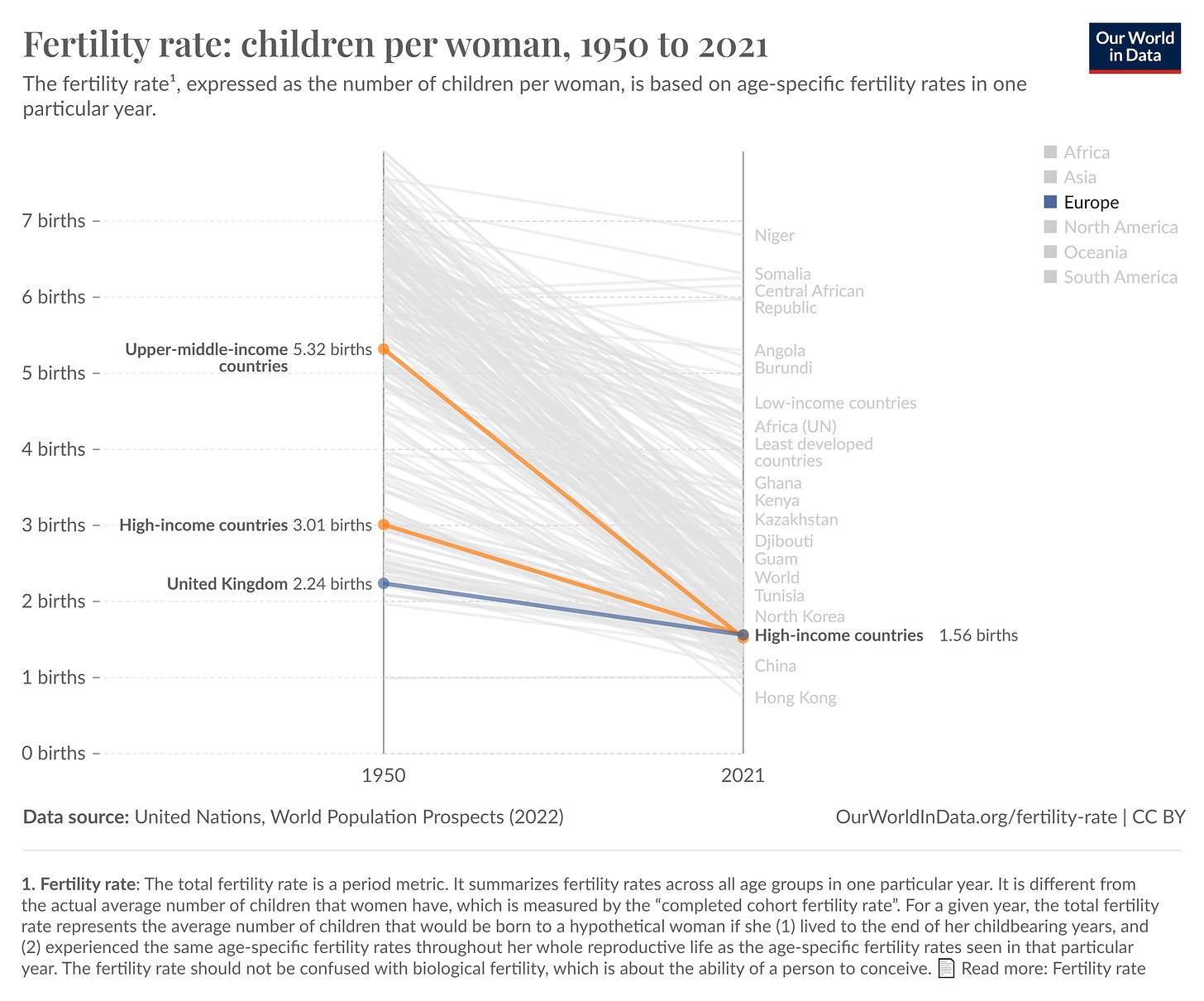

Biological reasons are next. In a sense, we need only at this juncture examine a single chart:

There is something about the conditions of modernity, that is, which are in themselves suggestive of decline and disapperance, and suggestive of a new world soon to spring into being; whether we like it or not, it seems that the culmination of secular modernity is a society in which people choose not to reproduce in sufficient quantities to maintain the population. We do not even need to know the exact reason for this – though you will have a hard time persuading me that it is not connected to any of the other issues raised in this post – and nor do we need to express a view about its normative desirability. We only need to observe the growing childlessness of the societies around us, and the brute fact that the ideologies which sustain them will in the fullness of time peter out and be replaced by something more evolutionarily vigorous – not in the sense of an ethnic ‘great replacement’, but in the sense of being swept away by a commitment to (pre- or postmodern) values and norms which promote childbirth.

And spiritual reasons – actually the most important – come fourth. We all, I think, know something very significant, which is that the world which we are creating for our children is, to put the matter frankly, a bit crap at best, and actively dehumanising at worst. This world – in which everybody is atomised, individualised and interested ultimately only in themselves; in which nobody appears capable of doing much at all other than being passively entertained; in which we are encouraged at every turn to look only downwards or sideways rather than up; in which our aspirations are driven ever more narrowly to the world of hedonic experience; in which we are told that our goals should only ever be to be equal rather than to excel – is modernity itself, and we are increasingly coming to the view that we don’t like it, though this inclination remains, at the moment, half-formed.

In particular, the disillusion with the technological aspects of modernity are becoming acute. This manifests itself in the observations that the internet is in general becoming ‘enshittified’, that it is ruining childhood and that it is turning young people off music; that AI deepfakes are going to make trust in media completely collapse; that modern architecture is intrinsically dehumanising, and so on and so forth – ad almost infinitum.

And we can layer on top of that the way in which the initial promise of the internet (i.e., that it would be fundamentally liberating), as naïve as that was, has been corrupted to the point of almost becoming inverted, such that it is fast becoming a tool for manipulation and control – leaving aside all of the many reasons why the experience of going online is becoming steadily worse. We are reaching an inflection point, though we have not quite got there yet, at which the cool thing to do will not to be online much, if at all, and in which indeed the only way to be free will be to not have an online presence, since the very act of online engagement will involve total surveillance and perfect censorship. We can I think, as Ted Gioia recently put it, feel this in our collective gut. That feeling will get stronger.

While we are, then, as moderns, on a clear trajectory, as I previously described it, towards that ruthless and remorseless future wherein all borders and distinctions are destroyed and all human phenomena are centralised in the centripetal point of the technocratic state, it is not a trajectory that can ever hope to reach its culmination. As the process plays out it will in fact become clapped out; it will make our lives more and more miserable, and sooner or later as a result it will stop. Modernity itself, the world which we have created, will be sloughed off, like a chrysalis or the dead skin of a snake, and something other will emerge – more grounded, more real, more human, though the process may be long or short, and may take on the character of violent revolution or quiet decline and renewal. It will be, I am sure, a more religious future, a more deontologically oriented future, a more open and expansionary future – though there will be pain and suffering in the interim, and thereafter, since neither of those things are in the gift of humanity to overcome. It will not be a return to the past, which is dead and gone, but to a markedly different future to the one which modernity presents to us.

This may very well not be a future in which digital tech is abandoned entirely. But it is one in which that technology will by and large be put in its proper place as a useful tool for certain purposes, and that alone. We will be its masters, rather than its ‘users’. While I do not, in other words, think that either of the scenarios I presented at the beginning of this post are entirely plausible, the one in which our lives go on becoming more and more digitalised into infinity is by far the least realistic. It is an eventual return to the prioritisation of physical reality which I see within our future. And I am willing to stake my life (well, okay, a box of Maltesers) – on that likelihood.

Dr. David McGrogan is an Associate Professor of Law at Northumbria Law School. You can subscribe to his Substack – News From Uncibal – here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

No British government, as we head into totalitarianism, is ever going to get rid of the state propaganda service.

https://www.theguardian.com/media/article/2024/jul/12/keir-starmer-commits-to-keeping-bbc-licence-fee-after-years-of-tory-hostility

Doctors Want Covid Jab Suspension – latest leaflet to print at home and deliver to neighbours or forward to politicians, your new MP, your local vicar, online media and friends online. We have over 200 leaflet ideas on the link on the leaflet.

Looks like Dr Malcolm Kendrick mostly won his case against the Daily Mail over statins-

https://drmalcolmkendrick.org/2024/07/11/a-little-more-on-the-trial/

Well cardiovascular disease has always been with us, I suppose, and has various causes, but it would seem demand for cardiac care is outstripping supply. So with regards to this record high number of people awaiting treatment, I’m baffled;

”Brits are being warned to look out for symptoms of a deadly disease, as the number of people awaiting heart care in England rose to a record high. The latest NHS figures show cardiac waiting lists rose to 421,433 at the end of May 2024.

This is an increase of 2,394 on the month before and the highest total on record. Since May 2022, the heart care waiting list in England has grown by nearly 100,000 people when the waiting list was at 327,258 – an increase of 29 percent.

This has been branded “frightening” by the British Heart Foundation (BHF), which is calling for the Government to prioritise cardiovascular disease treatment. Dr Sonya Babu-Narayan, BHF associate medical director and consultant cardiologist, said: “I find it frightening that long waits for time-critical heart care are putting people at risk of life-long disabling heart failure or death.

“That’s why it’s so disheartening to see the latest figures continue to show the worst access to vital, timely heart care in living memory. We cannot and must not get used to these unacceptable figures showing too many heart patients waiting too long.

“Getting to grips with this cardiovascular disease crisis and getting back to gold standard heart disease prevention, early diagnosis and treatment must be a priority for our new Government if they want to avert yet more avoidable heartbreak and loss of life.”

https://www.gloucestershirelive.co.uk/news/health/heart-disease-10-symptoms-9407051

The BHF are a fake charidee. It wholly supported the Scamdemic, masks, lockdowns, the works. An absolute bloody disgrace.

I saw a vid clip of Dr Malhotra admitting that he is also ”vaccine injured” the other day. That’s all he said on the matter, but he may have elaborated further in a different part of the interview, I didn’t watch the full thing. Because of his profession, and how he works in the private sector now, he could’ve ran various tests on himself in order to find any abnormalities, or perhaps he presented with clinical symptoms, not sure which. Maybe someone else on here has more deets…But going by various studies that’ve been done now, there’s an awful lot of people wandering around with subclinical heart damage and they’re completely unaware. So does this essentially make them ticking time-bombs, and we’re seeing the results of the mass jabathon experiment in the stories we read and the increase in stats, such as the ones mentioned above, and the excess deaths, of course? Then there’s the cancers that’ve increased, etc. The trend seems to be getting worse not better. But I think all of this has been obvious to we on here for a long while now. Props to Dr M for confiding this information about himself though, and continuing his fight to expose the serious damages done to us in the name of ( laughably ) ‘public health’.

Thanks Mogs

“calling for the Government to prioritise cardiovascular disease treatment”

Of course they are as that will provide greater research funding opportunities for the BHF.

Haha, see how the leftards kick off when you blaspheme against the Alphabet People cult.

But somebody ought to remind this awesome, truth-telling lady ( with the gorgeous hair. I’ll take this screenshot to my hairdresser ) that women’s secret weapon is that they were born hermaphrodite, thereby it is exclusively down to them if they produce babies or not. No requirement for the cooperation of a willing male whatsoever, therefore the decreasing birthrates are down to them and them only….Which is the ‘logic’ of the resident women-haters. Well, I think we all know you can’t reason with stupid, delusional people who are fueled by their innate bitterness by now.

”Slovakia’s minister for culture blamed the LGBT movement for Europe’s plummeting birth rates, arousing the ire of left-leaning ideologues.

During a July 3 interview with Slovak tabloid Topky.sk, Culture Minister Martina Šimkovičová blamed LGBT ideologies for Europe’s dropping fertility rates.

“We heterosexuals are creating the future because we make babies. Europe is dying out, babies are not being born, because of the excessive number of LGBTQ+ (people). And the strange thing is (that it’s happening) with the white race,” the minister said in comments cited by left-liberal news outlet Politico.

“We are living in an amoral era,” Šimkovičová elaborated.

In response to Šimkovičová’s July 3 comments, Peter Weisenbacher, director of the Bratislava-based Human Rights Institute, lodged a criminal complaint with the general prosecutor’s office against the minister, alleging that her remarks were racist and anti-Semitic.

In another interview, the minister admitted that “we are a sick society.”

In January, Šimkovičová revealed that the country’s culture ministry would cease financing LGBT projects.

“The LGBTI+ organizations (…) will no longer parasitize on the money from the culture department. I will certainly not allow it under my leadership,” Šimkovičová wrote on Facebook.

She added that she “rejects progressive normalization” and that her plans are for “a return to normality.”

Besides her anti-LGBT views, Šimkovičová has been noted for her tough stance on immigration, much to the chagrin of the globalist elites in the European Union (EU) and their ideological allies. To address the issue of Slovakia’s falling population, the EU elites have suggested bringing in migrants instead of encouraging Slovak families to have children.”

https://www.lifesitenews.com/news/slovak-culture-minister-triggers-leftists-by-blaming-lgbt-ideology-for-low-birth-rates/?utm_source=most_recent&utm_campaign=catholic

” No requirement for the cooperation of a willing male”

a ‘willy’ed male!

Agree about the hair, gorgeous

and agree with her veiws, not saying its the whole cause, but this celebration of non proliferation certainly doesn’t help the matter

Yeah she speaks as she finds, and speaks perfect truth, as far as I’m concerned. So if stating inconvenient facts ruffles the Leftards’ feathers and upsets their snowflake-like sensibilities then more power to her elbow. She’s over the target.

U.K. hasn’t allowed Ukraine to use Storm Shadow missiles inside Russia, MoD clarifies

Order, counter order, disorder. Welcome to your new government.

This one seems to be run by the Grand Old Duke of York. The only difference is that ten thousand men might be a bit of a stretch these days…….

What”s really going on?

Topical because, apparently, it’s not just Britain that is a bit short of troops.

The Russian military is redeploying wounded soldiers to frontline combat in the Kharkiv direction.

Social media images show soldiers from the 26th Tank Regiment, located northwest of Vovchansk, visibly injured, in casts, and on crutches, being sent to the front lines despite still undergoing medical treatment.

Remind me, who was the last ‘admired political operator’ who did this to his soldiers?

Oh yes, it was Saddam Hussein.

Whatever happened to him?

‘Nota bene’

Hussein was the Western governments kind of leader, then he wasn’t. Similar to Vladimir Putin but dealing with Putin in the same way isn’t so easy.

Zelensky is currently the Western governments kind of leader – ‘nota bene’.

“Half of Cabinet accused of house-building ‘hypocrisy”

And we’re do they stand on wind turbines?

Is Ed going to have a dozen of them around his house?

He’s declaring war on nimby’s let’s not forget!

I wouldn’t necessarily say it’s hypocrisy to represent the interests of the people whom you were elected to represent.

“How the White House hid the truth about Biden’s decline from the world”

They just denied it, they couldn’t hide it,

It was plain for anyone with eyes to see!

“James Cleverly leads race to replace Rishi Sunak, poll suggests”

James Cleverly? OMG! Is that the best they’ve got? Jumping jehoshaphat, Cleverly by name but certainly not by nature!

“It won’t be long before the Muslim Vote poses a real challenge to Labour”

It won’t be long before the Muslim Vote poses a real challenge to

LabourBritain!

I have been posting about this for some months now. Perhaps Frank Haviland has been reading DS.

Highly likely Hux

This presupposes that voting will produce a government representing the population rather than other interests. This seems contrary to reality no matter how many Atheists/Muslims/Jews/Christians/Hindus get elected.

However, it’s a good way to keep people in fear and distracted for 5 years in the lead-up to the all-important 2030.

“We will stand with people staring down the outrage mob” – A joint op ed in the Australian by the leaders of the four Free Speech Unions urges people to band together to defend the most important human right of all.”

Excellent! Please print out that statement by the Four Free Speech Unions somewhere on the Daily Sceptic, so that we can all read it (access to the Australian blocked).