“When I took over security there were no measures for MPs. There was so little for us. We didn’t matter. I hope that people will recognise what I have done, and stood up, and made sure that we can feel safe.” So began Lindsay Hoyle’s Speakership of the British House of Commons. Hoyle came to the role at the tail-end of the constitutional crisis over Brexit – which had its symbol in the fractious and imperial Speakership of John Bercow, his predecessor. Here was Bercow’s big idea: to conflate the administrative procedures of the House of Commons with the ‘rule of law’. In this way, an inflated Speakership and its parliamentary allies were able to hold the body in stasis for two years – unable to move legislatively, and unable to dissolve itself. By late 2019, this wrangling had failed. If the parliamentary opposition to Brexit had wanted to continue the fight, then it could have elected Chris Bryant, who offered to carry on with Bercow’s bumptious style. It did not.

Hoyle’s rise to the Speakership, then, was an aesthetic choice, not a political one. It was an acknowledgement of defeat and exhaustion. Hoyle, who had served as Bercow’s deputy, was far more circumscribed both personally and politically. With the arrival of a Brexit parliamentary supermajority, Hoyle promised to return the office to its traditional role: clerkship, not power. Hoyle the man had a number of appealing characteristics. He was old. His voice – endearingly – would haltingly stop, start, and loll from side to side. He was quaintly old-fashioned: the ‘at home’ photoshoots, of which there were many, revealed a riot of quilted couches, doily flaps, and floral carpets. Significantly, he was Northern – almost parodically so. The ‘Left Behind’ of the North would deliver Boris-Cummings its majority; Hoyle would be the ‘Left Behind’ Speaker, their spiritual representative.

Every Speaker has an official portrait made, and Hoyle’s appeared last month. We may have expected something in line with his own pipe-and-slippers style; something akin to the portrait of Neil and Glenys Kinnock in which both are sat comfortably in their kitchen, surrounded by an assortment of staring knick-knacks.

Little could prepare us for what was instead unveiled. The portrait, the handiwork of Australian artist Ralph Heimans, slams you in the face. It has a dull, throbbing intensity. It is painted in the realist style, but there’s nothing natural about it. It’s more real than real: the metal looks more like metal than metal; Hoyle looks more human than a human. No one feature pops out; every detail is accented and accented again, keyed up to its absolute limit and often well beyond it. There is nothing for the eye to rest on. It is matte, dense, and headache-inducing. It is insane. This is the painterly maximalism of a chocolate box, stretched across an entire canvas.

But it would be lazy and wrong to dismiss this as kitsch – though it certainly is. The portrait owes a certain debt to Norman Rockwell, maybe. But that isn’t the whole story. The glazed mania of this picture moves well past mere schmaltz.

For one, there’s the treatment of its subject. Hoyle’s Northern jollity is gone. This is someone in his full swagger, at the height of his secular powers. This Hoyle is a man of action and policy, and knows it. Our first comparison surely isn’t Rockwell, but royal portraiture – in particular, Hans Holbein the Elder’s lost rendering of Henry VIII. But even Henry disarms himself a little for us. In his arched eyebrows, in his small half-smile, we see something playful and self-aware about his own brittle arrogance.

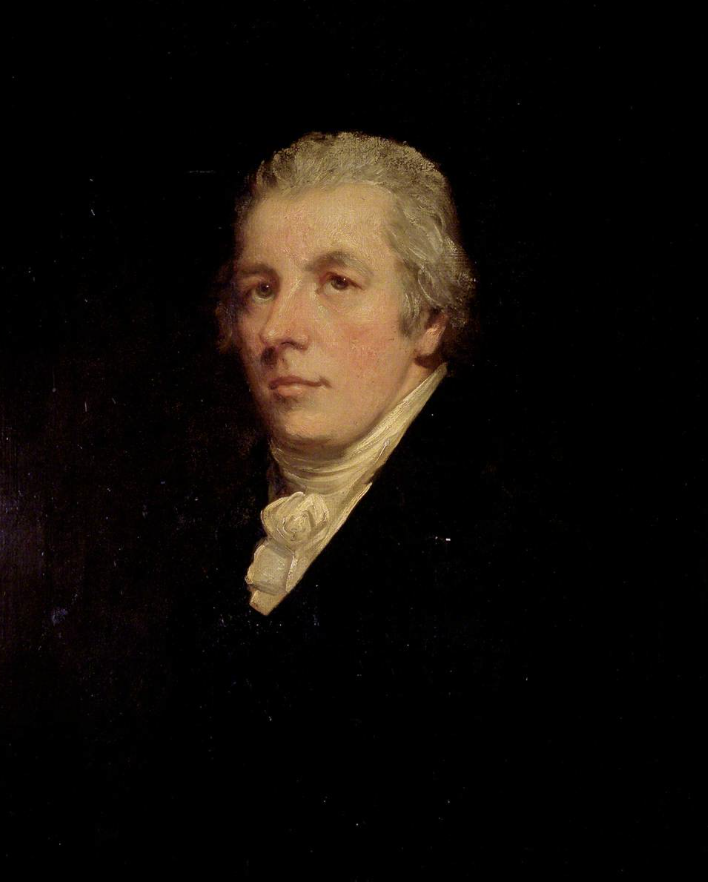

Scan the images of other powerful people from past ages, and you’ll find the same candour and intimacy. Subjects were relaxed about letting themselves be depicted in less than heroic terms. The famous plea to be portrayed ‘warts and all’ was the rule, not the exception. Look at John Hoppner’s 1805 portrait of Pitt the Younger – then also at the height of his powers. We’re able to catch this famously bloodless man at an unguarded moment, lost in thought, and a little bored.

Here we see a post-war Herbert Asquith, baffled and beaten, slumped over a writing desk. Two more end-of-career depictions, one a bust of Harold Macmillan, another a portrait of Harold Wilson, take this method a little further. The expressionist smears and dribbles seem to deconstruct the two, but never take them apart entirely. They remind us that they are merely people; their existence, even as grandees of national life, is as contingent and ephemeral as everyone else’s. Merely people, but, above all, people to be reckoned with, people whose faces have been lined by lives of excitement, intrigue, and the cares of command. These depictions are unsparing, and tender.

Heiman’s Hoyle does not let us in in this way. His expression is one of dead-eyed self-assurance. His smile reveals nothing, and yields nothing.

Why doesn’t it? This is a portrayal of one of the most visible fixtures of Britain’s governing class, a class that – as Hoyle’s earlier quote shows – sees itself as very much under siege. This is not a picture that can afford to be subtle, or playful. Authority is attacked everywhere, and cannot let its guard down. Artistic taste has changed to match. British art is now tasked with asserting the grandeur of the country’s reigning social order, against enemies both foreign and domestic.

This can explain Hoyle’s otherworldly stare. Authority has become deathly serious, and cannot present itself as wan, ironic, self-effacing, or vulnerable in any way. In this effort, Hoyle – as ever – does his duty. He fixes his eyes on the viewer, piercingly. It is an expression of reassurance, but also of command. Underlined here, too, is the enlarged power of the Speakership of the House of Commons. The defence of the current social order, which values procedure above all else, requires the destruction of the elected politicians, who alone have the power to change these procedures. The Brexit supermajority elected in 2019 has not been willing to break with this basic idea, especially after the resignation of Boris Johnson. As such, it never broke up the imperial Speakership established by John Bercow. Speaker Hoyle has inherited these powers, undiminished. Hoyle took up the role with a promise to reduce its influence. But he has not been able to resist the spirit of the age, which loves nothing more than a strivingly modest defender of procedure. The frivolous expulsions, the arraignments, the solemn speeches – these have all started to creep back in, as have the old Bercowite shrieks from the chair. “In this house, I’m in charge!” Hoyle bellows down to Boris Johnson. Hoyle’s commanding aspect, then, declares that the Bercow experience will not just be an aberration. It announces the arrival of the Speakership as a permanent and powerful factor in national life.

What also distinguishes this portrait from Rockwellian kitsch is its use of light. Everything in the picture emits a ruddy, radioactive glow: the walls, the windows, the tiles, Hoyle himself. According to Heimans, this is his own homage to chiaroscuro, a technique in which strong contrasts of dark and light are used to suggest volume, and to isolate a subject from its surroundings. But Hoyle is anything but isolated. He doesn’t stand out from the background at all. Everything lies flat on the same plane; the effect is to make Hoyle seem inextricable from his surroundings.

This is only fitting. In the post-Bercow era it is increasingly common to treat parliament not as a sovereign body, but as ‘The House’: a bundle of custom, tradition, procedure, and permanent staff. And now run, apparently, with quasi-judicial methods: as we have seen, it is now possible for an MP to commit statutory offences against The House. The fact that the Palace itself is falling to bits only increases its appeal. The increasing prominence of Westminster staff, and the welfare of MPs, makes this shift clear. This is no longer a body, but a place. It is a place superintended by an extended cast of lovable sprites: Blackrod; Clerks of the Commons in faded formal dress; Larry the Cat. Each are the keepers of this twisted Gormenghast and its lore, and are ready to see off any unwelcome intruders. Hoyle – and the Speakership in general – has become one with the Palace of Westminster, which is no longer the mere host to a democratic assembly, but a force unto itself.

Glance at the portrait of Michael Martin, another of Hoyle’s predecessors, and you’ll instantly cotton onto this change. He’s standing in the Commons chamber itself. The place looks palpably bigger than him. This is the point. Speaker Martin was a minor official, tasked with the day-to-day management of something larger than himself: a sovereign democratic authority. In the end, the task was beyond him, and he resigned in some disgrace. But he never pretended to be the master of the place, or the people who were elected to sit there. We find no attempt at usurpation in this picture.

The Hoyle portrait underlines all these changes political and sentimental. In the 2020s, Britain’s ruling classes feel under attack. They cling in trembling to ritual and procedure, the last defence against the populist challenge. This is an apologia that lends itself to saccharine and schmaltz, and Britain’s artists have responded. Some have dubbed this new sentimental style ‘Carolean kitsch’, or ‘Stakeholder Realism’. Hoyle’s portrait is its first great artistic statement. It is the house style of a social order under attack; a social order which can only portray itself with hysterical earnest.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Little corrupt men in surroundings and history they don’t even comprehend. Cometh the moment cometh the midget like Hoyle. A court Jester in the real House of Lords, or House of Pharma-ment as it became under Hoyle. A midget Jester who was involved in a coup against reality and the common peasant – us. A loathsome twisted group of little people, criminal in intent and action. That is all Hoyle et al are. The portrait should be of a demon in a cage.

looks like Anthony Fauci

Thank you for an excellent piece.

Clever Ralph Heimans, keeping the patron happy and offering us all with a shocked laugh of recognition.

A Parliament of Fools, indeed.

My first impressions – a slightly smug, holier than thou countenance which is polished to parody but very fitting given the decidedly feminine, arched eyebrows – a nod to the trans mania of the times perhaps ? In reality Hoyle’s face is normally full of notlrthern wear and ruggedness and what is presented here is all surface glow. It is a picture of dishonesty and as such very appropriate for our times.

Not a particularly pleasant picture to look at so entirely in keeping with Britain today.

I hope the tax payers did not fund the Kinnock picture. He has received more than enough from them already, as has his family.

The big mistake was to let this professional political class come into existence.

The easiest and most practical way to prevent and abolish it would be to introduce term limits, at most two, better just one.

But they will never agree to abolishing themselves.

And it leaves the, thereby further strengthened and equally power drunken, civil service to deal with.

This meme and the Dalio cycle explain them and it further:

When he published it, he thought we are at stage 15.

Clearly, we are at stage 17 now.

Hence their panicking, expressed by ever more authoritarianism and ruthlessness.

I’m not well-educated about art (paintings) and I found this article very informative and interesting. If I was forced to have one of these paintings hanging in my living-room, I’d choose the one of Harold Wilson, it’s pleasant to look at. I like the painting of Pitt the Younger too. I definitely wouldn’t want the portrait of Hoyle in my living-room, it’s quite depressing.

Reminds me of the following from serial civil servant Dame Glenys Stacey in her review of DEFRA regulations:

“All regulation is to get people to act in ways that they may not otherwise choose, in furtherance of the government’s aims. Regulation is all about changing people’s behaviours, and it helps to keep that firmly in mind.”

So there. In other words, they know they can’t command agreement, much less respect, so can only “win” by tangling their opponents in a web of tortuous, arcane procedure, the ‘rules based international order’ no-one voted for. Sooner or later, “the rule of law” ends up being “the rule of lawyers”.

‘Stakeholder Realism’ Haha! That made my day

Is it the painting in the painting that has the real significance?

If we want to look at the wood, at least let us see the trees as well.

In that other painting, is Charles I at or on his way to his trial? Two courtiers are kneeling. Is the king on his way to his execution? The 17th century style of dress of the Speaker makes commerce with the time in the other painting.

‘Authority is everywhere under attack’. The Stuart king would have agreed with that. But whose authority? And what sort of authority? Parliament’s authority is represented in the painting by the Speaker, contrasting with that of Charles I’s penchant for the style of Louis XIV. The point was crudely emphasised by the scriptwriters in the 1970 film, Cromwell, another piece of art, where old warts-n-all was depicted, ludicrously, as a democrat and Charles I as sneering at the idea of democracy.

In the painting, the Serjeant-at-Arms, carrying the mace before the Speaker, is included, unlike in paintings of other Speakers. This object of authority dates from the time of Charles I’s son and a different style of monarchy. Speaker Hoyle is depicted having an unshakeable, direct gaze at the viewer. Both his countenance and bearing, combined with the details of the whole setting, could be read as an assured depiction of parliamentary authority. That authority restored after a turbulent time of constitutional crises resulting from the constitutionally unwise 2016 referendum. The ‘time of healing’ has had it’s effect today, just as it did after the turbulence of the 1640s.

As for Pitt the Younger, a contemporary described him as being stiff with everyone, except the ladies.

“constitutional crises resulting from the constitutionally unwise 2016 referendum”

Well referenda are tricky, but then so is governing a country by any means. It may have presented some awkward issues, but I for one am damn glad that we had one, and my side won, and we’re out of the EU and able to dig our globalist, WEF-inspired grave without the EU badgering us to do so.

The crisis seems to me to have been caused by large numbers of MPs of all parties pretty much reneging on the deal – many of whom voted in favour of having a referendum in the first place.

Methinks It flatters him immensely, the guy is a clown masquerading in his finery!

I might not know art but I know what I like!