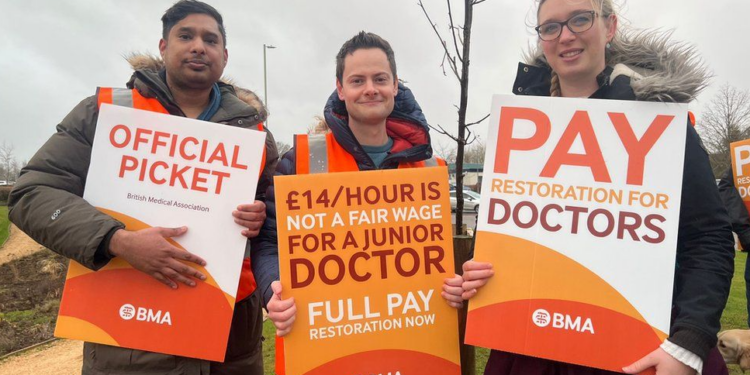

It’s been a busy couple of weeks on the healthcare news front. Industrial action continues apace, with junior doctors declaring a further five-day strike in mid-July and hospital consultants voting for strike action shortly thereafter. In the Guardian on Thursday, Professor Philip Banfield of the BMA exults that all English doctors could be taking strike action before the next election. Banfield states this is precisely the BMA’s intention.

That the BMA is inciting politically motivated strikes is no surprise – the union has been run by Left-wing agitators for many years. The main bone of contention is ostensibly financial – the BMA demand a 35% increase in basic pay across the board for all grades of hospital doctor. The cost to the taxpayer of such a demand is hotly debated. Estimates for full settlement of the junior doctors’ pay claim range from between £1 billion per year (BMA) to double that amount (HMG). The cost of the consultant pay demand would be substantially more expensive. Assuming a reasonable mid-point estimate, the BMA is probably demanding an extra £4 billion per year in taxpayer’s money.

Closer inspection suggests all may not quite be what it seems on the barricades. For example, the nursing union failed to secure a mandate for further strikes, and the junior doctors’ action may also be wavering. During the last juniors strike, some hospitals reported 70% of their trainees turned up for work. It is important to remind readers that the term ‘junior doctor’ covers a wide spectrum of medical practitioner – from the newly minted F1 houseman fresh out of medical school in his or her early 20s, to the senior registrar in his or her mid- to early 30s, with 10 or more years of hard work invested in their careers. Many older trainees with family commitments can’t afford to strike, nor have their valuable training time reduced by industrial action.

My understanding of the current situation is that more experienced medical trainees are either reporting for work as normal on strike days or making money by doing extra shifts to cover absences of their younger colleagues – at pay rates of up to £269 per hour.

The strike is still disruptive as a lot of routine work has to be cancelled. On the other hand, it is a manageable situation as the die-hard militants are mostly drawn from the younger group of juniors – the equivalent of medical toddlers. This cohort are easily replaceable by more mature practitioners for short periods of time.

A consultant strike could be a different beast. Consultants are fully trained and accredited specialists – in short, no clinical work can happen without a consultant assigned to supervise it. Yet again, there is more to this action than meets the eye.

The union publicly exhorted members to vote for strike action, even if the individual had no intention of striking, in order to ‘send a message to the Government’. The proposed consultants action involves providing ‘Christmas day’ cover – in other words a full emergency service but no elective work. This is a strike deliberately intended to disrupt efforts to reduce waiting times for patients. It remains to be seen how many consultants will actually turn up for work as usual, despite the strike vote. That said, even if a surgeon arrives for a planned operating list on a strike day, the list still can’t proceed if the anaesthetist is on strike.

I think it helpful at this point to explain just how consultant specialists are paid. There has been a good deal of argument in the deadwood press as to the precise amount consultants earn, with every claim and counterclaim subject to traditional accusations of ‘misinformation’ and subject to contentious ‘fact checks’ by BMA agitators. Having spent 20 years as a consultant, I can shed light on this byzantine system for readers with the stamina to stick with the detail – you certainly won’t read this information anywhere in the mainstream media. The remuneration system goes some way to explaining the productivity conundrum – why NHS productivity continues to fall, and the system continues to underperform despite more money being spent and more doctors recruited.

Consultant time is remunerated per ‘programmed activity’ of four hours – abbreviated to PA. Hence a 40-hour working week constitutes a 10 PA job plan. The basic salary rates quoted by the BMA are on a sliding scale from £88,000 for a newly qualified consultant to £128,000 at the top of the scale. There are several important points to note when interpreting what the BMA says. The first is that not all new consultants start on the lowest salary point – those with post-fellowship qualifications may start several points up the scale. The second point is that this is an upwards-only increment – in other words, progression up the scale is related purely to time in the job. There is no requirement to achieve certain milestones, or hit productivity targets – simply keeping breathing and not getting fired is sufficient to get a pensionable salary increment, before any nationally agreed pay increase is added. Given that it is virtually impossible to be fired as a doctor, pay progression is assured.

The figures quoted do not include various add-on supplements. For example, there is an extra pay award for intensity of on-call, for London weighting and for extra duties such as managerial roles. Consultants can also apply for ‘clinical excellence points’ which accumulate and can make a substantial contribution to take-home pay. Doctors taking on extra work can be awarded extra PAs – in my time working for the NHS it was not unusual for some colleagues to be on 13 PAs, effectively enhancing their base salary by 30%.

The definition of a programmed activity is open to negotiation in the yearly job planning process. About 25% of a doctor’s time is allotted to ‘supporting activities’ – teaching, audit, participation in mandatory training and various other administrative tasks. Even PAs for direct clinical care of patients can be modified to include time taken on writing letters, travelling between hospital sites and a multitude of other tasks not involving patient contact time.

Annual leave allowances are generous. The BMA states that consultants are entitled to six weeks paid annual leave per year. Again, in fact the allowance is more than stated. Once bank holidays and various other entitlements are considered, most hospital consultants get between seven and eight paid weeks of holiday per year. In addition there are 10 days per year of paid study leave or professional leave to attend courses and conferences. Doctors involved in national bodies such as the many Royal Colleges, professional associations or in academic practice can negotiate much more paid leave than this. It is not uncommon for some NHS consultants to be absent on paid leave for nine or 10 weeks of the year.

Contrast this system with remuneration in private practice. In the private sector a doctor is only paid for directly relevant clinical services. Doctors are not paid for all the necessary administrative tasks involved in running a practice. There is no paid leave of any kind – no holiday pay, no sick pay and no study leave. Nor are there any pension entitlements. Financial incentives in private practice are aligned to encourage direct clinical contact. In the NHS it is the other way around.

NHS consultants can also be remunerated (in addition to their base salaries) by taking on extracurricular activities for NHS England or other national bodies. Consulting work for the pharmaceutical industry or medical device companies is commonplace. Some consultants earn significant extra money by writing medical reports for the legal system.

And then there is private practice. It is important to state that a minority of NHS consultants do a large amount of private work. Nevertheless, the nature of job planning usually leaves at least a whole day a week free for private practice, plus evenings and weekends. A moderately industrious doctor in a reasonably affluent part of the country should be able to clear £80,000-£100,000 per year net of expenses from private practice without too much extra effort.

The NHS itself also provides opportunities for additional income by laying on extra clinical sessions outside agreed job plans to reduce waiting lists – simply put, if patients cannot be treated during normal paid working hours, the NHS will pay consultants extra to treat them in the evenings and at weekends to meet political targets. Several enterprising companies have started highly lucrative ‘insourcing’ ventures – where NHS staff use NHS facilities outside normal working hours to treat NHS long waiters. NHS managers look kindly on these companies, because the ‘optics’ are preferable to passing over large numbers of long waiting patients to private hospitals for treatment – if patients are being treated in NHS facilities, it looks like the NHS is managing the process by itself, even if a private company is actually involved.

And then there is the pension. It is certainly the case that NHS pension entitlements reduced when the 1995 final salary scheme was changed to the 2015 career average scheme, but benefits are far better than anything available in the private sector. For example, higher earning consultants pay 13.5% of their pay into a pension (with tax relief), but the employer pays in an additional 20.5%. This is the reason why there was such squealing about the pension lifetime allowance and reduction in tax relief on contributions. But pensions are just a mechanism for deferred payment and need to be considered when assessing overall remuneration levels.

Many consultants approaching retirement have substantial benefits in the 1995 scheme – inflation linked to final salary with a normal pension age of 60. Such schemes are no longer available in private industry, for a very good reason – they are too expensive to run. But, if one’s employer is the British taxpayer, no scheme is too expensive for the BMA.

Finally, consider this. A high proportion of NHS consultants are married to other NHS consultants or to GPs. I can’t find any statistics on this point, but in my own social network I estimate that over 50% of my peers are married to other medical professionals. That’s two sets of taxpayer funded salaries and pensions per household. I’m not claiming such couples don’t deserve their financial compensation – medicine is a highly demanding and stressful occupation which carries a significant personal cost for many practitioners and doctors work hard for their money. Even allowing for my obvious bias, I doubt many people would push back too strongly on that point. However, a demand for a 35% increase in salary by the BMA is surely unjustifiable when taxes are already at a 70-year high and many working people are struggling to make ends meet. I entirely agree with Banfield that many senior doctors are highly stressed and angry. My perception, however, is that discontent about pay is secondary to dissatisfaction with the coercive NHS system, intimidatory professional regulation and intense organisational friction. I may examine those points in more detail in future.

The British Medical Association would do the nation a service if it focused its effort on enhancing NHS productivity. Unfortunately, the union prefers politically-motivated industrial action intended to facilitate the election of a malleable socialist Government. Prepare for more boondoggles masquerading as patient care in our wonderful NHS, which remains of course, the envy of the world.

The author, the Daily Sceptic’s in-house doctor, is a former NHS consultant now in private practice.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

I’ve been out of medicine for 15 years, and was a GP rather than a hospital quack. But I fully endorse your assessment here. As in every profession, if you let doctors get on with doing what they’ve been trained to do (and more importantly, developed a personal nous for over the years), you can get away with underpaying them and produce only grumbles.

Treat them as jobsworths, and they become jobsworths, to nobody’s benefit. But as we all know, you can only run a world from the top down if everybody is a jobsworth.

They can go on strike, as long as they want.

If I can stop being taxed to keep the NHS on perma-lifesupport.

And as for missing out on some future treatment by Ranjit, Retard and Dizzy Blonde.

I’ll take my chances, thanks.

I’m sure that many people who dont come into contact with its world, see the BMA as a passive and moderate organisation furthering the care of patients. Thats a long way from the truth. Very interesting article again Doc.!

What a joke. £100K or more + a MASSIVE PENSION + 40 hrs a week in the communist death care system. SHUT IT ALL DOWN. START AGAIN.

I pay absurd amounts in taxes. I have private medical insurance paid by myself.

We need a system with competition, price points, quality and service.

Most importantly – these arselings loved Rona, they made record earnings, they danced in diapers in empty hospitals. They are criminals who stabbed poisons into people with ingredients they can’t spell or pronounce against a scamdemic. Cowards and criminals.

And the criminals want more of my tax money? F Off. You are fired.

….just over 151 million jags have been given out in total, in the UK…

4 million ‘spring boosters’ just this year..at (now) £15 per vax (up from £12.58) to the Doctor or pharmacist, or ‘paid volunteer’ (£20 on Sunday and Bank holidays…and £30 if it’s a home visit…….!!)

As Del Boy would have said ‘a nice little earner’…!!

“Jags”?

A Scottish colloquialism, M’Lud.

Stabbinations is also good.

LOL! Picked it up on here…yes it is Scottish jab/jag…..a lot of people have used it in the past….I like a change from quacksines now and again!! LOL!!

Haha, never heard that one. And given that I’m from Newcastle, and we get the dregs of Scottish lingo, it’s surprising.

I love your common sense “to the point” attitude, it rocks!

Well as there’s no News Round-Up today I’ll just dump this here. Looks like our Nigel isn’t the only one being targeted and bullied by the banking sector;

”An Anglican vicar has slammed Yorkshire Building Society for closing his account after he accused them of promoting gender ideology.

Rev Richard Fothergill, a longstanding customer with the building society, wrote to them in June to complain about their public messaging during Pride month.

The 62-year-old says within four days, he received a reply telling him his internet savings account would be closed, The Times reports.

Rev Fothergill, of Windermere, Cumbria, has since accused the banking giant of ‘bullying’ and said: ‘I wasn’t even aware that our relationship had a problem. They are a financial house – they are not there to do social engineering. I think they should concentrate their efforts on managing money, instead of promoting LGBT ideology.

‘I know cancel culture exists and this is my first first-hand experience of it. I wouldn’t want this bullying to happen to anyone else.’

The retired vicar insists his observations were a polite rebuttal of transgenderism, in response to material on YBS’s website.

But the building society wrote it has a ‘zero tolerance approach to discrimination’ and their relationship with the customer had ‘irrevocably broken down’.”

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-12253081/Vicar-accuses-Yorkshire-Building-Society-bullying-closing-account-trans-protest.html

This is particularly interesting because unlike banks, Building Societies are (ostensibly) democratic associations of lenders and borrowers, who elect a board to manage their stash. Shareholders are entitled to vote, and so should be free to initiate an AGM motion against promoting Pride.

So to close the account of a shareholder expressing an opinion is to uncover that the democratic nature of the society is a sham.

Excellent clear account of exactly how consultant pay is calculated. GP pay is similarly based on very complex arrangements.

it was crystal clear to me when consultant and GP contracts were renegotiated by the government some years ago that the bureaucratic system introduced for the determination of pay was open to widespread manipulation to guarantee the very best possible remuneration for the least effort. It was also crystal clear that administering such a bureaucratic payment structure was itself very costly and open to counterproductive abuse.

The medical profession at a stroke was reduced to a trade and, as we all know, a workman is “worthy of his hire”!

At one time doctors were treated as professionals and regarded themselves as such. They outperformed because it was their professional obligation. All extra effort above and beyond their contractual obligations was provided for love. Now every effort not required by the contract of employment attracts additional payment.

A prostitute won’t wash your socks for free! There is no love and no obligation involved for the oldest profession!

The most junior doctors have great justification for their pay claims to compensate for years of relative decline. With student debts of around £100k they are effectively paying a graduate tax out of a salary that does not begin to compare with that achieved by the brightest and best students who chose the private sector rather than public service.

Loan forgiveness for all junior doctors would go a long way towards ameliorating their current situation and earning their goodwill in return for a period of commitment to NHS service. There would be no immediate huge cost to the government and it would help those in most need now who have paid most to train as doctors. Since 85% of student debt is never repaid it seems like a common sense approach which is probably the reason it will never happen!

beanie, I basically agree. except that when the new GP contract was negotiated, the government side worked on the assumption that GPs were all workshy and on the golf course all day, so needed to be incentivised to cover things like chronic disease and so on.

They were warned by the BMA negotiators that most GPs were doing this extra work already without remuneration, as it had been devolved from hospitals over many years, and that therefore the costings were completely out. Gordon Brown personally rubbished the warning, and so the contract did not alter.

As a result, as soon as the new contract came in average GP remuneration increased massively, because of work that was already being done, and a government disinformation campaign began to persuade the public that avaricious GPs were always intended to spend the money investing in extra services rather than taking a pay rise for work designated in the item-of-service fees. That denigration of my decades of hard work for my patients was one reason I left.

No doubt there were, and are, workshy GPs gaming the system, and the system encourages it. But it’s also true that for decades beforehand the system was gaming the GPs by adding new work and staff costs without paying for it, by repeatedly cutting pay review body recommendations under the guise of “affordability.”.

Great article, thank you DS. Every article by this author has been extremely insightful and well written.

Sadly that is not the case for articles written by Ian Rons about Ukraine, which completely ignore the endemic corruption etc in Ukraine that used to be widely reported by the MSM, plus Nato’s role in reneging on the agreements made in the Minsk agreement; plus of course the US government’s role in overthrowing a democratically elected government. In addition – also ignoring the now well documented involvement of Boris Johnson sabotaging the draft peace agreement that apparently Ukraine & Russia were on track to sign. Of course there have clearly been atrocities on both sides – this is an appalling war as all wars are, but the DS is doing itself no favours by supporting this continued doubling down & wilful ignorance of the well documented other aspects of this awful situation. If the DS ends up losing its well deserved reputation for questioning the mainstream narrative – I will stop funding it.

If I was still working I would not be striking. The current pay demand is absurd in the current national financial climate. In my last 10 working years pay rises were less than inflation, and often less than the supposedly independent review body recommended. Did consultants strike then? We just grumbled. But a practical point… you cannot increase productivity if your outpatient clinic is limited in length, as my managers at the time insisted upon. You cannot increase operating time if there are not enough theatres to operate in, not enough staff to staff them, restrictions on start/stop times and not enough beds to accommodate postoperative patients. And if in such a constrained system you increase the number of consultants then productivity decreases per individual. I know of a provincial surgeon who used to have two NHS operating sessions a week, but with the arrival of new colleagues is down to one a fortnight. I know of few doctors who want to sit around doing nothing, so it’s hardly surprising they take to the private sector where they can actually do something.