This week the death of Nigel Lawson was announced. Readers may be aware that Margaret Thatcher’s prominent Chancellor famously compared the NHS to a “national religion”. The second part of his observation is more rarely quoted – to the effect that those who work within the NHS system regard themselves as a kind of priesthood.

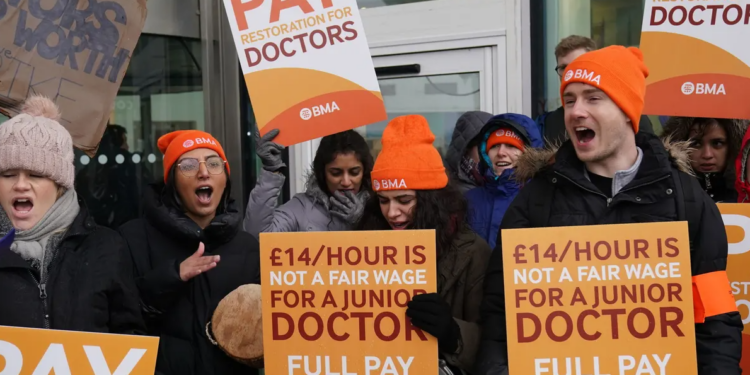

Lawson’s remarks were rarely so appropriate. The week following his death will see four days of consecutive strike action by junior doctors, accompanied by familiar incantations about how they are withdrawing their labour to save the NHS. The demand for a 35% pay rise is of course necessary to protect the system from the evil Tory Government and the privatisation agenda. Should readers wish to access any more of this propagandised pap, they are welcome to read the mainstream media. Here at the Daily Sceptic, we aim to provide more substantial analysis and to discuss the real issues behind the news – commentary which in polite society would certainly be characterised as ‘wrongthink’.

Many professional groups gripe about pay and conditions – disagreements between doctors and the state are by no means new. Doctors have taken industrial action of varying intensity on several occasions before, most recently in the junior doctors strike of 2016. The British Medical Association (the doctors trade union) has a longstanding tradition of opposing virtually every government policy, often in the interests of enhancing professional remuneration. So far, so normal.

On this occasion, however, I do think the current militancy represents something of a sea change in medical behaviour. This is a consequence of various structural changes in medical workforce matters over the past decade. It is important for readers to appreciate that the term ‘junior doctor’ covers a wide spectrum of practitioner, ranging from very recent medical graduates in their early twenties to senior trainees in their mid-thirties. In fact, the term itself is outdated and a better descriptor would probably be ‘doctors in training’ or similar. More senior trainees often have a different perspective than their younger colleagues. It is striking (excuse the pun) that the current junior doctor leadership seems to be drawn from the more inexperienced section of the junior doctor community.

The strike next week is the second round of the dispute. The first strike in March was unprecedented, in that junior doctors absented themselves from emergency cover for an entire 72-hour period. Readers may not appreciate what a big deal that is – to spell it out, the striking doctors refused to staff emergency rotas. This action left patients arriving to A&E departments with acute heart attacks, diabetic crises, strokes, car crash injuries and the like, with zero medical care. They also withdrew ward cover, so patients in hospital unfortunate enough to develop post-operative complications had no doctors to look after them. That’s apparently what it takes to save the NHS.

In actual fact, the first strike turned out to be a bit of a damp squib. Hospitals managed quite effectively to reallocate consultant level doctors to cover emergency and ward work. Paradoxically, emergency care pathways were more efficient than usual, as senior decision makers processed patients much faster than trainee doctors. This of course came at the cost of cancelling the vast majority of routine outpatient appointments and operative procedures – adding still further to the legacy of lockdown.

Managing the second round of strikes might not be so easy. The second round has been deliberately timed for after the Easter weekend, when a lot of consultants will be away on leave. In effect, the strike leadership is ensuring that there will be no routine work carried out in the NHS for a 10-day period. Major operations can’t be undertaken if there is doubt about the provision of 24/7 medical care, so no significant procedures can be done safely in the days leading up to the strike action. It is notable that senior hospital managers have been encouraging consultants to engage with the press emphasising the risk to patients – normally managers hate doctors talking to the press, but in this case there seems to be an intention to undermine the strike. It is unlikely that round two will be the end of this dispute and further escalation is quite possible. It is inconceivable that these young doctors are unaware of the effect their action will have on patient care. It is highly likely that some patients will be harmed as a result of this strike and some may well die as a direct consequence of industrial action – this is several orders of magnitude more significant than not being able to get on a train for a few days.

Readers may very well be wondering how it has come to this. Until recent times, a doctors strike would have been inconceivable. Of course, the charge is often levelled that older clinicians tediously harp on about how much better things were in the ‘olden days’. For clarity I should state that things were not better, but they were certainly different. As this dispute is ostensibly about money and conditions, readers may be interested in a comparison of junior doctors’ pay rates in the late 1980s with the modern-day equivalent.

Until a decade ago, hospital-level care was delivered by small teams of doctors, called ‘firms’. A typical firm comprised one or two consultants, a senior trainee and two or three other juniors. Being on a good firm was hard work but great fun. Patients got an excellent deal from the ‘firm’ structure, because it provided continuity of care – the same doctors looking after the patient throughout their time in hospital and afterwards in outpatients. Payment for medical time was split into four-hour blocks known as a UMT (unit of medical time) – so the standard 40 hour week comprised 10 UMT’s, paid at a basic rate. Junior doctors then had compulsory ‘on call’ UMTs – the standard for a one-in-three on call rota was 13 additional UMT’s. These were paid at 30% of the standard rate – please note, that is 30% of standard, not 130%. Junior doctors on call were the lowest paid workers in the hospital, with an hourly rate of pay less than that of the cleaners – far lower than the current remuneration. On the upside, the work was so intense and the hours so long that junior doctors were provided with hospital accommodation free of charge. Work life balance was perfect, because work and life were the same thing.

The reason I point this out is that low hourly pay rates for junior doctors is not news. Nor is it a secret. It cannot come as a surprise to any newly qualified doctor that the pay in the early years of medical practice is not great. About 15 years ago, the structure of junior doctor terms and conditions changed substantially. The ‘firm’ structure was abolished and on-call rotas were changed to shift patterns. The driving force behind this change was the assertion that long hours were dangerous for patients and damaging to doctors. There was some truth in this view – mistakes were made by tired junior doctors, myself included. Unfortunately, the cure turned out to be worse than the problem.

Loss of the firm structure demolished continuity of care and made the whole process of looking after patients very inefficient. The complicated shift systems proved unwieldy, inflexible and very unpopular with juniors. Not surprisingly, junior doctors remained unhappy with their pay and conditions – they were doing far fewer hours work than their predecessors and therefore lost free accommodation. Total pay reduced (because of a lower on-call commitment) and workforce surveys revealed far lower levels of job satisfaction than under the old regime. The numbers of doctors in training increased substantially, but their pay fell in real terms, because each individual was doing less work. Needless to say, this was entirely predictable and indeed was predicted at the time the changes were proposed.

Discontent with shift-working and its remuneration formed the basis of the 2016 strike, which ended in a comprehensive defeat for the doctors. A face-saving, window-dressing compromise was agreed which failed to address any of the real grievances. The current dispute in many ways is continuity 2016, driven by a more militant and explicitly Left-wing cadre of political activists.

It is often trumpeted by the BMA that as a consequence of poor remuneration, U.K.-trained doctors are leaving for jobs in Australia. Ironically, the doctors union fails to ask why Australian doctors have a much better deal than their British counterparts working in the socialist utopia of the NHS. Might it be because the Australians have a mixed health economy, where hospital systems are competing for a finite medical workforce and therefore provide better terms and conditions? Isn’t this the same mixed economy model that the BMA regards as unsuitable for the U.K.? There must be a fair amount of cognitive dissonance going on in BMA House – but then the doctors’ union is adept at that and the wilful blindness that goes with it.

I think the real cause of the juniors strike actually lies in disappointed aspirations. Indoctrinated medical graduates have been led to believe that possession of a medical degree guarantees membership of the NHS ‘nomenklatura’. The reality is that doctors are simply part of the lumpen proletariat, with little influence or bargaining power. The likely resolution of this dispute is hard to predict at the moment. A lot will depend on how cohesive the strike is as the dispute escalates. The BMA junior committee has started with a very intense and prolonged industrial action. The Government will not give in easily, so the expectation must be that the strike committee will raise the ante. As walkouts become more prolonged, it is quite possible that their members may return to work, concerned about loss of pay and the effect on patients. More senior trainee doctors may worry about the effect on their training and future career prospects. It is not inconceivable that the vanguard of the proletariat could yet end up marching on its own.

The author, the Daily Sceptic‘s in-house doctor, is a former NHS consultant now in private practice.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Wednesday Morning Maidenhead Road & Forest Road, Three Legged Cross, Warfield Bracknell

“The Royal British Legion has been found to waste donations on diversity initiatives instead of helping veterans — costing at least 80,000 poppies”

It is a huge sadness to me that so many previously rock solid UK charities have betrayed their founders and their supporters, National Trust, RNLI, and now the British Legion. And yet so many of these Charities continue to trade on their traditional virtues and appeal for you to sign up and leave them money in your will. Well I am afraid my view is that charity begins at home and my will all goes to my family, what they do with any money that might be left is up to them. In my view many of these National and International charities have grown too big for their boots and have lost their founding principles and at the same time, in my case at least, have lost one of their traditional supporters.

Big Charity.

Never donated.

They’re all corrupt.

Charity begins at home, hear hear.

Donations to charities are simply secondary taxation for the gullible.

Completely agree. Used to have direct debits and gave donations to a few charities but stopped them all after I saw how they were wasting money on areas that were not part of their remit, plus how much they had in ‘reserves’. It’s all the same with these big organisations, it’s not their money so it doesn’t matter to them how they spend it!

Kamala Harris compares Trump to Hitler and calls him a ‘fascist’

Both Presidential candidates are fascists.

All Western governments are fascist governments

That is one reason why, in Britain:

‘Phillipson (is) targeting the most successful education policy of the last 14 years’

https://dailysceptic.org/2024/10/23/why-is-labour-axing-the-tories-most-successful-education-policy/

‘Big state’ is fascism, and fascism is ‘Big state’

‘many of the practical expressions of Fascism (are) party organization, system of education, and discipline……the outstanding importance of education.’

‘Fascism is therefore opposed to all individualistic abstractions based on eighteenth century materialism

‘Anti-individualistic, the Fascist conception of life stresses the importance of the State and accepts the individual only in so far as his interests coincide with those of the State’

‘It is opposed to classical liberalism which arose as a reaction to absolutism and exhausted its historical function when the State became the expression of the conscience and will of the people. Liberalism denied the State in the name of the individual; Fascism reasserts’

Benito Mussolini 1932

And we see, in stark clarity, in China, in Russia, in Iran, Syria, Yemen and elsewhere, the ultimate expression, the end point of fascism….totalitarian socialism, brutal repression, torture, war crimes and, essentially, hell on earth….

‘The Fascist State expresses the will to exercise power and to command. Here the Roman tradition is embodied in a conception of strength. Imperial power, as understood by the Fascist doctrine, is not only territorial, or military, or commercial; it is also spiritual and ethical’

And we see it within our own (and so many other) state education system(s).

‘Fascism, in short, is not only a law-giver and a founder of institutions, but an educator and a promoter of spiritual life. It aims at refashioning not only the forms of life but their content — man, his character, and his faith. To achieve this propose it enforces discipline and uses authority, entering into the soul and ruling with undisputed sway.’

Is there a certain uniformity discernible amongst the teachers and pupils of a homogenised state education system?

Philipson is intent on reinforcing it……..for votes, of course…….

‘The Fascist State is an inwardly accepted standard and rule of conduct, a discipline of the whole person; it permeates the will no less than the intellect. It stands for a principle which becomes the central motive of man as a member of civilized society, sinking deep down into his personality; it dwells in the heart of the man of action and of the thinker, of the artist and of the man of science: soul of the soul.’

That is ‘Big state’.

And we see, in stark clarity, in China, in Russia, in Iran, Syria, Yemen and elsewhere, the ultimate expression, the end point of fascism….totalitarian socialism, brutal repression, torture, war crimes and, essentially, hell on earth….

Interesting how you here list those countries currently opposing western doctrine, so who is actually suffering from whom?

China is doing its best to continue avoiding conflict with its business partners in the West. Russia is fighting against a union of 52 (?) western countries, all of whom deny they are directly involved in the fight except Ukraine, of course, and cry in outrage when they hear the nonsensical claim that one country, North Korea, is actually joining the fight on Russia’s side.

Then we have the US funded and unconditionally supported Israel, that just loves bombing Arabian citizens, whether inside or outside of Israel, originally an Arabian country called Palestine. The phrase ‘Hell on Earth’ has been often used there to describe the pitiful situation of the Palestinians imprisoned and bombed in Gaza as well as the current bombing campaign in Lebanon. And when Yemen actually voices support for Palestinians and closes down shipping in the region, of course USA and its partners are happy to bomb them too.

Iran is another country whose leaders dedicate themselves to a religion which is foreign to us, so they must also be attacked? They cannot be left alone to develop and flourish as a nation, hopefully becoming – should they wish – a more secular society? No, US leaders wish they should be destroyed, so we are just waiting for a war to start there too.

Syria is another country whose leadership the USA attempted to overthrow. Having failed, the remaining forces sulk away in the east in Syria’s oil fields, helping themselves to whatever they can take.

Of course it is a war crime to bomb civilians, except when performed or funded by USA or NATO. But here in the west we are also suffering from our less than democratic governments, happy to imprison and torture political dissenters – viz. Julian Assange, Reiner Fuellmich.

The BRICS summit is currently coming to a close in Kasan, Russia: an ever expanding group of countries around the world are tired of US hegemony and western sanctions trying to convert them to western ‘values’ which always remain undefined. The prime obstacle against a country joining BRICS is that they must never have sanctioned another country – how is that for a slap in the face to the good old EU, which now has 15 (?) sanction packages against Russia?

Since the Biden administration refuses to allow Russia to trade in US dollars or euros, Russia is forced to use alternative means. Now USA is in a panic because the BRICS countries are happily trading in their own currencies and the dollar is fast losing its position as the world’s favourite currency.

The world is an interesting place, we only have to hope we will survive any impending nuclear disasters.

‘China and India, which each have 1.4 billion inhabitants, are engaged in fierce geopolitical rivalry in Asia—and, increasingly, globally.

The two are locked in a territorial standoff in the Himalayas, maneuvering for strategic advantage in the Indian Ocean, and bickering over which is best positioned to serve as a natural leader of the Global South.

India is also a member of the Quad, a strategic partnership with the United States, Japan, and Australia, whose primary if unstated purpose is to prevent Chinese hegemony in the Indo-Pacific.

Scratch the surface, and geopolitical fissures emerge across the BRICS more generally. Consider the perennial topic of UN Security Council reform.

While all five nations are on record as supporting enlargement, they diverge wildly on the details.

China and Russia continue to resist any expansion of the council’s permanent membership—the precise status to which India, Brazil, and South Africa all aspire.’

‘BRICS Expansion, the G20, and the Future of World Order’ Stewart Patrick, 09 Oct 2024

Western press has been predictably reticent to even mention the BRICS summit, let alone publish anything other than derogatory articles on the subject.

It was announced on the eve of the Kazan summit that Beijing and New Delhi had reached an agreement on patrolling the line of actual control on their border, which is expected to help ease tensions in the region.

You can read the XVI BRICS Summit Kazan Declaration here: http://static.kremlin.ru/media/events/files/en/RosOySvLzGaJtmx2wYFv0lN4NSPZploG.pdf.

Point 3: We reaffirm our commitment to the BRICS spirit of mutual respect and understanding, sovereign equality, solidarity, democracy, openness, inclusiveness, collaboration and consensus. As we build upon 16 years of BRICS Summits, we further commit ourselves to strengthening cooperation in the expanded BRICS under the three pillars of political and security, economic and financial, cultural and people-to-people cooperation and to enhancing our strategic partnership for the benefit of our people through the promotion of peace, a more representative, fairer international order, a reinvigorated and reformed multilateral system, sustainable development and inclusive growth.

Note ‘promotion of peace’ and a ‘fairer international order’. Sadly they have also adopted the western terms ‘sustainable development and inclusive growth’ but nobody is perfect.

Point 5: We welcome the considerable interest by countries of the Global South in BRICS and we endorse the Modalities of BRICS Partner Country Category. We strongly believe that extending the BRICS partnership with EMDCs [Emerging Market and Developing Countries] will further contribute to strengthening the spirit of solidarity and true international cooperation for the benefit of all. We commit to further promoting BRICS institutional development.

Point 6: We note the emergence of new centres of power, policy decision-making and economic growth, which can pave the way for a more equitable, just, democratic and balanced multipolar world order. Multipolarity can expand opportunities for EMDCs to unlock their constructive potential and enjoy universally beneficial, inclusive and equitable economic globalization and cooperation …

Point 8 concerns the UN: Recognizing the 2023 Johannesburg II Declaration we reaffirm our support for a comprehensive reform of the United Nations, including its Security Council, with a view to making it more democratic, representative, effective and efficient, and to increase the representation of developing countries in the Council’s memberships so that it can adequately respond to prevailing global challenges and support the legitimate aspirations of emerging and developing countries from Africa, Asia and Latin America, including BRICS countries, to play a greater role in international affairs, in particular in the United Nations, including its Security Council. We recognise the legitimate aspirations of African countries, reflected in the Ezulwini Consensus and Sirte Declaration.

Note that UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres also attended the BRICS summit.

And so on.

The establishment of BRICS is a reminder to the U.S. and E.U. of the importance of deregulated free trade. Either the U.S. and E.U. return to the trading models that created their prosperity or their relative economic decline is assured.

However the BRICS group is characterised by a profound economic heterogeneity, spanning different continents and embodying diverse economic models from resource-driven economies to global manufacturing hubs. This diversity extends to key economic indicators.

Problems with BRICS expansion:

‘First, the decision-making would become a cumbersome process with too many members. BRICS decides by consensus, and achieving the consensus will become a herculean task.

The countries of the Global South are witnesses to the fate of NAM and G77, which still exist but carry little value.

Moreover, the organisation could end up reflecting the broader rivalries among members.

There is a genuine concern that geopolitical rivalry in West Asia may adversely impact its functioning.

Regarding de-dollarisation, Russia appeared keen to develop an alternate payment system for intra-BRICS trade. Russia has been kicked out of the SWIFT system and it wants to urgently develop an alternative payment system.

BRICS states, in general, endorse such an idea, but they do not necessarily share Russia’s enthusiasm.

The lofty idea of a BRICS currency was not even a part of the discussion at Kazan.

However, BRICS states support the idea of conducting trade in national currencies. Nearly 92 per cent of Russia’s trade with China happens in local currencies.

Moscow is also keen to expand this system with India and Brazil. But in cases where the trade imbalance is high, as in India, repayment becomes a challenge.’

Rajan Kumar

There is another major problem with all BRICS economies, rampant corruption; no doubt the reason why the U.N. secretary general attended Kazan.

A multi-polar world existed 1945-1990. That coincided with ‘The Long Peace’ in Western Europe. It also coincided with the decline and ultimate disintegration of the USSR.

Both China’s and Russia’s populations are declining. Their economies are likewise struggling. China has bet the house on green energy products. That strategy is not ageing well and if, as now seems likely, Mr Trump becomes President once more, China’s economic doom loop may very well accelerate.

The new ‘cold war’ might end in the same way as the previous ‘cold war’.

In your one post you quote a Stewart Patrick criticizing China and Russia for resisting any expansion of BRICS and in your last post you quote a Rajan Kumar as saying too many members would make decisions cumbersome to achieve: you cannot have it both ways!

To name rampant corruption as a reason for Guterres to attend the BRICS summit is far-fetched; I imagine he attended primarily because this important group of countries accounting for 35% of global GDP was discussing the UN and how it should be changed.

Your ‘Long Peace’ coincided with the Cold War when everyone had good reason to fear a nuclear conflagration. With respect to that fear, sadly not much has changed.

As for China’s and Russia’s economies and populations declining, you need to compare them with with the state of western economies and populations, the latter only being held up with massive illegal immigration. And I also disagree that China has ‘bet the house on green energy products’: China has made a great business out of selling such nonsensical products to the climate preachers of the west; furthermore, I have not heard of China closing down coal mines, steel works or sealing profitable energy sources, such as the UK is currently doing with great gusto.

Finally, whether BRICS will be a successful organization bringing economic fortune to its members and peace to the world is in the clouds. At least it is not yet binding its members to a myriad conditions, as does the EU, and if it succeeds in bringing an end to US and NATO militarism, the source of so many millions of deaths around the world, then that alone would be of enormous benefit.

The new cold war is very much a product of ‘Big State’ bureaucratic functionary fascism. Free trade encourages a multi-polar world. The U.S., Britain need to remember their roots as (relatively) free trading nations. For the EU, used to Napoleonic and Germanic restrictionism, that will be more difficult.

BRICS increasing diversity will make it even harder for BRICS+ to formulate, adopt, and pursue unified policy positions, including within the framework of the G20.

To date, BRICS has been more effective at signalling what it is against—namely, continued Western domination of the architecture of global governance—than what it stands for.

Developing a coherent, positive agenda for reforming world order and advancing international cooperation is likely to become even harder as the coalition adds more countries with very different political institutions, economic models, cultural systems, and national interests.

The initial composition of BRICS+ will also complicate its aspirations to speak for the Global South, further blunting its impact on global order.

The West must demonstrate to these countries that it welcomes (rather than seeks to block) the emergence of a more multipolar world, that it will not press them to make unrealistic choices about their strategic alignment, and that it is willing to negotiate openly on the rules of the road that will govern the future world order.

And welcome it, it should. For that way lies peace and prosperity.

The idea that the world has ever been ‘unipolar’ is complete nonsense. A multi-polar world is, has always been, the status quo.

English is an ancient trading language. The U.S. has dominated the new interconnected world of digital communications, in English.

Maybe that may have given some exaggerated impression of a unipolar world; an illusion.

The only real point is whether president Trump would be willing to work with him, when loyalty is one of Trump’s core values.

Um, you mean “core values” like all the times the AntiChrist Drumpf contracted work on his many properties, paying half of the agreed money beforehand, then when the work was completed, refused to pay the rest?

Or his “loyalty” to his deluded January 6th supporters, refusing to give them all presidential pardons while he was still in office, leaving them to rot in prison?

“Keir Starmer warns of ‘endless’ rows if Commonwealth pushes reparations claims”

Easy, disband the commonwealth!

Let them have their much vaunted independence

Stop all foreign aid

This is a peculiar post. The countries in the Commonwealth already have their independence. It is a voluntary association that now includes some countries that were never ruled by the British; they actually wanted to join! Only a few have asked for reparations and on this I agree. The idea is absolutely absurd.

And some have a much higher per capita income than us.

I’m sure I’m not the only one that thinks the commonwealth is a lot more ingrained into being British territories than they actually are, but thanks for the more indepth information 👍

It’s a complete Scroungers Society, draining money in “Foreign Aid” out of the pockets of UK Taxpayers and into the pockets of Third World politicians. And there’s even more to pay, now that the Commonwealth has been expanded to include former French, Francophone colonies like Gabon and Togo. They want to join to get money, and more will follow. The Commonwealth has never been of the slightest benefit to the people of Great Britain, just an albatross around their necks.

“The most recent members to join the Commonwealth are Gabon and Togo, who joined on 29 June 2022. They are unique in not having a historic constitutional relationship with the United Kingdom or other Commonwealth states.

Also called “The Marxist Redistribution of Wealth” to destroy the West.

Seconded.

“On Substack, Paul Sutton gives his thoughts on Peter Lynch’s death.”

And in this rather lukewarm article he makes this statement about Peter Lynch…

“…he was clearly a disturbed individual.”

Nothing to back up this assertion. Quite grotesque and cruel.

Paul Sutton needs to edit this article because this is an insult to the memory of a brave man, killed by Kneel and one of his corrupt ‘judges.’

The trouble is, I think all these patriots who’ve been wrongfully jailed ( I make exception for the ones guilty of arson as burning a building with people inside is never justified ) have been given duff advice from the duty solicitors to plead guilty so that they’ll get a lesser sentence and be out sooner. But Mr Lynch still got 2 years 8 months! Was he going to serve just 40% of that and if so was he told this? The vast majority of people were just concerned citizens who’ve never been in trouble with the law and who got caught up in the moment. Where was the harm done? Some words on a bloody screen? Where’s the proof anybody incited anybody to commit violence? Yes Mr Lynch called the police ”scum” and banged on their shields a bit, but 2+ years inside??

Then you’ve got that stupid Telegraph article above where Starmer is saying he never wanted prisoners to go free early but the prisons are at ”bursting point”. So ”bursting” he goes and shoves loads of people in there that don’t deserve to be there? He’d rather have murderers, paedophiles, wife-beaters and kidnappers roaming the streets than keyboard warriors and those attending protests? He’s full of shit and it’s bloody insulting everybody’s intelligence!

It wouldn’t surprise me if more of these poor people end up either topping themselves inside or getting attacked and killed because crims have found out who they are, but I obviously hope I’m wrong. I’ll bet they never in a million years thought they’d be doing time for writing something angry online or swearing at police and their dogs. That’s got to be a shock to any decent person’s system. Be found to be in possession of thousands of child sex abuse images on the other hand and the judges take pity and sympathize with you. Sick Clown World version of justice.

Top class Mogs.

A woman was stabbed in Walsall at the weekend and has subsequently died in hospital from her injuries. Apparently she worked at the migrant hotel there. This from Twitter, with details not provided in the news articles;

”In Bescot, Walsall on Saturday night a women was stabbed at the rail station. She has subsequently died. A man is charged, so far, with attempted murder.

A number of citizen journalists & followers DM’ed me to said the suspect lived in Bescot Crescent, the site of an asylum hotel.

Another tells me a police turned up the next day mob handed. Coaches were hired to take them to another location. ”

”In Bescot, a woman, 27, has been murdered at the station, Deng Cholmajek, 18, has been charged with attempted murder.

I have seen multiple sources say she was an employee at the asylum hotel.

It’s alleged the murderer complained about the food the victim said “I don’t prepare it, I only serve it”.

At the end of her shift he followed her out.”

https://x.com/DaveAtherton20/status/1849144444609503619

I thought the name sounded a bit East European but somebody in the comments has helpfully ascertained it’s Sudanese, where they’re 97% Sunni Muslim;

”Deng, Chol and Majak/Majok all listed as Sudanese names.”

https://500wordsmag.com/suda-lists/traditional-south-sudanese-names/

Bit more detail regarding the above murder;

”In Bescot, Walsall Rhiannon Skye Whyte, 27, was murdered. Deng Cholmajeck’s charged with attempted murder, will be charged with murder. He’s thought to be an asylum seeker, staying at the Park Inn Hotel. One of my followers gives us some context what it’s like to live nearby.

“Hi. Yes that’s the one sir! I live nearby & often fish the river that runs along the hotel. I have sat & watched numerous times as groups of men leave the hotel in the middle of the night & wander off along the nearby woods into the darkness.

“The site is right next to Walsall football club & numerous fans have complained about harassment but the Home Office have assured the club the guests are now having English lessons which I suppose is tax payer funded.

“Nearby car parks have seen an increase in break ins Either way I think the club has upped security. Our local news teams & police force have turned off all comments on posts surrounding the stabbing.

“I’m walking round today so I’m hoping I can send over some pictures to confirm anything further but police have cordoned the hotel grounds off.”

https://x.com/DaveAtherton20/status/1849381625479491811

https://www.conservativewoman.co.uk/no-boris-you-cant-wriggle-out-of-this-immigration-fiasco/

Dr Mike Jones at TCW taking a knife to Bozo Johnson’s typical re-writing of history in this case the horrendous rise in immigration. The usual “it wasn’t me wot done it” is proven to be a typical lie. And Johnson is such a lazy criminal that he blames the Scamdemic for all of it.

Perhaps if you had had the balls to call out the covid scam the country wouldn’t be in the utter mess it now is eh Mr Johnson? Oh, but that would have required balls wouldn’t it?

What’s one more sex attack by a migrant? Stabbings, sex attacks…they all blend in and become part and parcel of what we’re to accept as commonplace these days. That way it is hoped we become desensitized and immune to feeling outrage and anger at what’s being done to us. Less likely to oppose and put up resistance, our kids living in increasingly risky communities. This here isn’t even a city, and by the sounds of the article he won’t be being deported or even doing any time, just moved on to become somebody else’s problem when he inevitably does it again;

”A 16-year-old boy arrested on suspicion of sexual assault was living at a military camp providing accommodation for Afghans fleeing the Taliban. A representative from Swynnerton Training Area made the disclosure during a public meeting in Yarnfield last night.

The boy was detained on Sunday afternoon after a girl reported being sexually assaulted at Yarnfield skate park. Staffordshire Police have since bailed the boy to live outside Staffordshire.

Hundreds of people attended last night’s meeting organised by Yarnfield and Cold Meece Parish Council on the Labour in Vain pub car park. StokeonTrentLive reported in February how up to 200 fleeing Afghans were due to move onto Swynnerton Training Area.

A Ministry of Defence official told the meeting: “We have been working since Sunday alongside Staffordshire Police after the initial response by them and during the investigation and, as has been alluded to already, the individual who was arrested on Sunday was an under 18, so a minor who was currently at that time living at Swynnerton, one of our Afghan communities. We have probably got about 23 Afghan families living at Swynnerton in the camp where you’re probably in the past more familiar with seeing army reserves or cadet forces or similar using at weekends and during the summer. It’s a fairly transitional approach. They arrive here in the UK and indeed it’s the first port of call for them having arrived here is to come and live in somewhere like Sywnnerton. They should only be here a number of weeks, some have been here longer.”

https://www.stokesentinel.co.uk/news/stoke-on-trent-news/boy-16-arrested-over-sex-9658598

“Police who shoot suspects to be granted anonymity during murder trials after Chris Kaba case”

NO! Police who shoot suspects, or kick suspected terrorists in the head to neutralize the threat, must NEVER be tried for murder or any other crime, just for doing their job, as they are trained to do, in order to protect the public and their fellow police officers from being killed by criminals and terrorists.

Just as our Armed Forces must NEVER be tried for murder or any other crime, just for doing their job, as they are trained to do, in order to protect the public and their comrades-in-arms from being killed by the enemy in warfare, including the warfare caused by Catholic Terrorists in Northern Ireland.

“Keir Starmer warns of ‘endless’ rows if Commonwealth pushes reparations claims”

JUST SAY NO! Don’t waste any time on discussion of these outrageous proposals from Commonwealth Grifters.

Abolish the Commonwealth. If they want to set up their own Third World Grifters Society and discuss it endlessly among themselves, they can.

“NO” means “NO”, once and for all.

I was disappointed to not find an article here about the enormous lorry fire on the M25. Oh yeah, it wasn’t an electric vehicle fire.

https://www.express.co.uk/news/uk/1964747/m25-traffic-live-motorway-closed-lorry-fire