It’s cold here in London, and it’s getting harder to resist the temptation to turn on the heating. Which prompts the question: how much are these high energy prices costing the country?

Some data are now trickling through. The British government recently released figures on the state of public finances, and they make for grim reading. In December of 2022 the UK government borrowed more money than it had in any other December since records began in 1993.

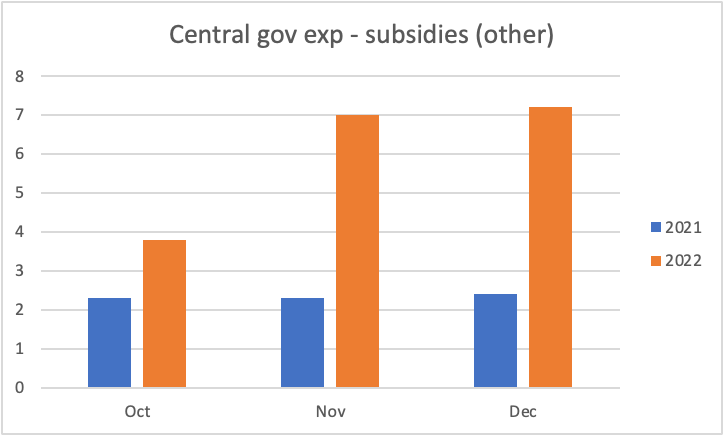

Driving this borrowing were two things: higher interest rates and energy price subsidies. The latter are included in the line item ‘Subsidies (Other)’ on the government balance sheet. Here is that line item, in billions of £s, for the third quarter of fiscal years 2021 and 2022.

We can estimate from this that in the third quarter of fiscal year 2022, the government borrowed around £11bn to spend on the energy price guarantee. Taking the December numbers alone, for every £12 the government borrowed £1 was spent on the price guarantee.

Now, the Modern Monetary Theorists – who it must be said, with COVID-19 and the chaos in energy markets, are having a good decade so far – will tell us that since the UK issues its own currency, it can borrow as much as it likes. There is some truth in this. Nevertheless, if the UK borrows and spends and this money flows abroad it will (all else being equal) put downward pressure on the price of sterling. If sterling falls, the price of imports rise – and real wages fall.

With a little statistical manipulation, we can use the government borrowing data to estimate the current account – the amount of money flowing into and out of Britain.

The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy informs us that without the energy price guarantee, the price of energy for the average home would be £4,279. Since the price guarantee ensures the average household pays £2,500, we can infer that the government is covering around 42% of the current energy price. This implies that for the £11bn the government spent on subsidies in the third quarter there was an additional £15.5bn spent by households. This means that the total spent on energy in this period was around £26.5bn.

Now we can use this estimate to estimate the current account. Britain imports around 50% of its gas. So let’s assume that around half of this £26.5bn was spent on imports. That gives us an estimate of the British current account in 2022 as follows.

It is easier to compare this data annually. The chart above implies that in 2022 the British current account deficit will be around 6.4% of GDP. This would be the largest current account in British history – the previous two largest being 5.5% of GDP in 2015 and 5.2% of GDP in 2013.

The country has managed to sustain this current account so far with only some disruption to sterling. But can it sustain another year of this? That is far from clear. Yet many are predicting that 2023 will be a worse year for energy prices than 2022, since Europe had access to six months of Russian gas last year and won’t have any this year.

Of course, these are all just estimates that require us to make various assumptions. What is clear is that the government borrowing data for subsidies implies a substantial increase in the amount of sterling flowing abroad to buy energy imports. Which doesn’t bode well for Britain’s finances.

Philip Pilkington is co-host of the Multipolarity Podcast. You can follow him on Twitter here and subscribe to his Substack newsletter here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

My nhs trust has announced that while it’s ok to accept cheap gifts in kind this year, we should only accept ones that can be wiped down (eg cellophane wrapped), and it is recommended that the gifts are put in quarantine for 48 hours. You couldn’t make this shit up!

All ‘gifts’ should go straight into the incinerator. And make sure you have your fireplaces filled with roaring logs to burn The Virus off Santa when he comes down the chimney.

Fan the flames by leaving the window wide open, and don’t forget to park granny right beside it.

‘cos you can never be too careful. All about safety innit?

Literally insane.

Absent office environment for 30+ years; what was the name of that Round Robin game in which everyone great and small is anonymously selected to buy a present for a random other (max £5.00 or so).

“Secret Santa” rings a bell.

Obs if I got selected to buy a present for a Covidiot it would either be luxurious packaged sanitizer or a bumper pack of the cheapest face masks.

But if there’s a crease in the cellophane – then what?

You can be safe in the knowledge that there will be no gifts to the NHS from me this year thanks to their selfish and disgraceful attitude of late.

“…thanks to their selfish and disgraceful attitude of late.”

Thank you for putting me straight about my attitude. Not sure my patients would agree with you though.

And of course this saves money for the companies.

The gullibility is staggering.

On a brighter note I was at a party last night in a large hall and it was packed. Two hundred plus attending. Everybody hugging, kissing, shaking hands; it was heart-warming to see.

Had a party like this myself lately. Everyone behaving completely normally with the exception of some managers who were fist bumping. I refused and held out my had to shake!!

Last year, before the churches were closed (!!!), there was service at which this ghastly fist-bumping and elbow-bumping was ‘recommended’. I walked out at that point.

This happened to us, 400 UK staff + partners was deemed too much of a risk. Why we are not considered adult enough to manage our own risk was not explained.

I suspect they aren’t worried about the risk to you, more the risk of half the company having to isolate at home after and how much they would be demonised in the press if anyone dares to die over xmas.

The Office Xmas party scene has been a shadow of its former self for years dating back to when companies that provided free alcohol became responsible for the behaviour of their staff and guests until they reached home.

This meant that if, following a perfectly well behaved, if riske, performance at the Company party, Daryl and Ryan from Accounts later got plastered at a Nitespot before beating someone up, their employer could be held responsible.

Same applies in the case of staff driving home from the Company do when over the limit and causing third part damage.

Spot on. A long time ago, I was, at various times, “management” in three of the largest UK advertising agencies. The Christmas parties were something else, at places such as Stringfellow’s and The Pheasantry in Kings Road. The drink that went down was incredible, as were the Polaroid photos of various persons “in flagrante”. At one agency, we had as clients Vauxhall, Goodyear and the COI Road Safety campaigns. Anyone caught driving drunk in a company car after the Christmas parties would have cost us the accounts, worth £millions. The hotel bills (Claridges, Savoy etc.) and the taxi bills (Brighton, Home Counties) that the company paid were out of this world.

Latterly, as a self-employed person, my parties had but one attendee, which was far less stressful.

Ah, the Original Office Christmas Party…those were the days! When it actually was held in the office and not some overpriced venue charging through the nose per person for some scraps of food (we had pay for ourselves!) Where everyone went but didn’t really want to go, where you go “for just the one” and end up staying to the bitter end, where some bright spark suggests “going on to somewhere else”…where you enter the zone of the “lost hours” with just a few vignettes to remind you where you were and who with, and somehow you manage to find yourself staggering in at about 5am with absolutely no idea where time went. And all the gossip the next day, hoping you’re not part of it! I almost pine for those days again!

This ^^^^ totally .

Last time I did that was only 4 years ago. 3 parties in a week, Tuesday Wednesday Friday three different companies one I consulted at ( Tuesday ) some of us ended the evening at Spearmint Rhino. One I owned ( Friday ) I consumed enough alcohol to kill a small horse then spent Saturday morning in bed in a hotel with my ( then ) mistress.

Happy days.

I no longer drink at all or have a mistress.

Happier days now but kinda miss the old days.

Brilliant. Thanks.

The so-called “Nudge Unit” (aka Reichsministerium für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda – Goebbels’ Department for Enlightenment and Propaganda) have much to answer for.

It will take a generation or more for this accumulated fear to be bred out of the population – and that’s if we start now.

‘has’ much to answer for. Oh for an edit facility!

There is an edit facility that lasts until 10 minutes after you post OR until someone replies to it.

It’s the little gearwheel/cog icon to the right of the word ‘reply’.

Disappears after 10 minutes

Queenie says: “I wasn’t wearing a face mask at the G7 Party!”

It’s not just office parties that are being cancelled it’s also children’s school Christmas plays both in the state and private sector. Apparently some local authorities are advising it’s not advisable for groups of parents and children to be mixing. Meanwhile in the real world they are all getting together in restaurants, parks etc. The killjoys are still keen to cancel Christmas.

Fortunately I think privately many are ignoring this rhetoric.

We have a house full of friends this weekend. Great stuff

Anything to avoid bother or responsibility, these people really are using Covid to suck the joy out of of life in a way not even seen during WW2 which really was an existential crisis.

Killjoys have had Christmas for themselves every day since last March.

…Such as the 40-something nurse who visits my elderly neighbour every morning to supply her with opioids, alternating between arriving in two different cars, for both of which presumably expenses are charged. She always scrupulously dons her hi-vis jacket for the 3ft walk across the deserted pavement between whichever car she is driving and my neighbour’s gate. Gotta wonder whether she clicks her heels at the threshold. Invigorated since the onset of fascism last year, she has now taken to telling me off for running in the morning without armbands, claiming she can’t see me until I’m nearly under her wheels or flying backwards over her windscreen. But the fact is that there’s a damned pavement all the way from the beginning of my run to the end, which obviously I always stay on. People like her are walking 10 foot high at the moment. Make no mistake – when the time comes to round up the unvaccinated, many such “killjoys” will be in seventh heaven.

Anyone who hasn’t yet read Stanley Milgram’s book on his electroshock experiment, or watched the superb film “Compliance” (2012), I would beg you to do so.

The juxtaposition of ‘fascism’ and ‘armbands’ in your post brought an interesting picture to mind!

Insecurity takes many forms.

On a rare venture out of doors earlier this week I was pleased to see a group of a dozen or so children from the nearby Junior school waiting on the kerb to be shepherded across by their teacher. All wore hi viz smocks but no masks.

I can only assume they were headed for the park at the end of my cul-du-sac where they have a much neglected herb garden set aside for their use. Happy days returning again one would hope.

We should not cease from repeating the fact that, at this point in time, such caution (if necessary) indisputably proves that official management of this virus (if you accept it as a big deal) has been an utter, bollocking failure.

Watch this space. Last week, son took all his staff out as a thank-you for their performance over the last year. So 40 people packed into bars and then a restaurant all evening. I will report back as to whether they were compromised.

And to make it worse, some are spending their time manning a stand at an exhibition, mingling with the great unwashed, over the weekend.

Shocking disgusting behaviour!!!

No fun should be had by anyone!!!

I will relay your message to him, but I suspect I know his answer.

GMB pioneered this a few weeks back.

Bedwetting pish from businesses who believe vaccines don’t work.

I would rather repeatedly smash myself in the face with a mallet than attend my company’s Xmas do. It’s not that I’m unsociable or that I don’t like Xmas, but quite frankly I spend enough time with my tosser colleagues all year without having to then pretend I’m enjoying a third rate turkey dinner and watching them dancing badly to Slade afterwards.

Yes, it must be bad enough working in an office or for some white-collar outfit all year round, either in the private sector or the public sector, let alone attending the “Every Fool Can be a King for 10 Minutes”, “World Turned Upside-Down” pre-Christmas event, the function of which is to get people to knuckle down to all the bullsh*t during the rest of the year. There are examples of this in many horrible cultures. Be “cynical” for a day and then lap it all up for a year, then repeat.

I committed the cardinal sin of not attending the Christmas party at a former job. The boss took it as a personal affront. I attended the next year, and may have done something ‘untoward’ because when I didn’t show the year after that he didn’t say anything at all.

I used to argue with my schoolfriends that Slade were better than T-Rex, sadly I was wrong but ‘Merry Xmas Everybody’ has stood the test of time better than anything from Mr Bolans ouvre

Come to my party!

Ours is going ahead, for now, no restrictions I am aware of. The organisers did a poll to see if people would come and the response was strongly in favour – we shall see if people go through with it.

I remember these parties and corporate events, always cringeworthy attempt of the business types to “improve teamwork culture” by making office workers pretend they love to have fun with each other. The reality is if you sit with someone in the office the whole day (even if they are cool, decent people), you are not very inclined to spend even more time with them after work or party with the same people. I for one am very glad I no longer have to participate in them (independently from the pandemic).

The spike protein and cancer???

Spike protein inside nucleus enhancing DNA damage? – COVID-19 mRNA vaccines update 18 – YouTube

Yep: a little Doomsday machine. If it doesn’t get you quick, it’ll get you slow!

For many of the vaxxed it will be their last Christmas. They should party like there’s no tomorrow.

I’m sure the “risk of covid” is not what they’re really worried about. They’re worried about the very real risk that Saint Boris will wobble, will cave to the pressure for lockdown, just like he did last year, forcing the party to be cancelled. “I won’t cancel Christmas, it would be inhumane … oh… I’ve just done it.”

Best bet would be to use outside caterers with a ‘no charge if cancelled by bozo’ clause, leave them to worry about the insurance and wasted food.

Good opportunity for those back at work to turn up in droves at the homes of those still working from home and demand a party! Can’t really see why any DS users would want a firm’s Christmas party to mix socially with sheep unless to enjoy watching the hypocrites at play.

I hope those who attend Christmas parties this year have fun, whether they’re sanie brainers or jabby pod clot-bots (in the latter case, perhaps try a game of “Pin the Braincell on the Smartphone User”?) – because this may be the last real-life Christmas party that you go to for a long time.

Latvia is already under a countrywide 8pm to 5am curfew.

Austria will put the unvaccinated under limited house arrest from Monday.

Interesting to see Prof Neil Ferguson, the infamously inaccurate doomsday modeller (and now self appointed vaxx expert) waxing forth today in favour of boosters; having doubtless been instructed by his paymaster Gates to do his duty. The BBC is giving full coverage to this latest intervention(of course):

‘Rolling out booster jabs to younger age groups could help cut Covid infection rates to low levels across the UK, a leading scientist has said. Prof Neil Ferguson said data suggests a third jab gives significant protection, even against mild illness. He said he saw “no reason” why younger age groups should not be offered boosters after priority groups.

He also said the UK was unlikely to get a “catastrophic winter wave” this Christmas.’

Of course he never explains how a vaxx that doesn’t stop either infection or transmission (by the maker’s admission) can be of any use anyway.

There was once a time when most vaccinations were for life, otherwise they were just called treatments. Administering an experimental drug (indeed any drug) via a needle never before conferred vaccinated status, but I guess if the WHO now say it does it must. mustn’t it?

PS: Good job we don’t have to keep trooping back every 6 months throughout our adult lives to the doctors for TB, Smallpox etc or we’d have arms like pincushions and the NHS would be overwhelmed…

:

So the corporate blob cancels the parties.

Organise your own, but don’t invite the Lockdown Stasi. Make it clear they’re unwelcome.

#Direct democracy.

How about a massive, country-wide Christmas party for all the healthcare workers, first responders, etc. who were sacked for refusing the jab? There’s a party!

The geniuses are locking down again (courtesy of Tom Woods)

Today someone shared this chart, generated by the Financial Times. Try to pick out which one of these countries hasn’t implemented a vaccine passport system:

https://mailchi.mp/tomwoods/lockdowneurope?e=6fe7ac95b6

Christmas is when individuals and employers show their true colours

I have fond memories of a super-spreader at our office parties.

Its almost like Bernard Manning is back amongst us

If only!

The company I work for had a business conference at the NEC recently and aside from the NEC requiring you to have an NHS covid pass ( proof of vax or negative test LFT or PCR) to enter, I wouldn’t have known covid was a thing.

No masks mandate, no social distancing – I saw plenty of hand shakes and hugs, no awkward elbow bumps.

Must have been there with 3500-4000 other colleagues and only a handful of people had masks on (excpet NEC staff).

By the evening, when the free alcohol was flowing, not sure I saw a single mask – everyone dancing and having a good time.

The majority are over it, even those who have been bought into the narrative.

“…aside from the NEC requiring you to have an NHS covid pass ( proof of vax or negative test LFT or PCR) to enter, I wouldn’t have known covid was a thing.”

But that’s a huge thing, isn’t it? It’s crazy, given that the “vaccinated”, who are more likely to test positive for covid than the unvaccinated, can enter places without showing any evidence of current covid test status, whereas the “dirty unvaxed” have to jump through this hoop even though they are “safer” to be around than the vaccinated. I went to an English theatre recently, only because it was a booked performance that had been cancelled in the first lockdown, and my child was desperate to attend. I told them I was exempt from both the “vaccine” and from being tested. The person at the door looked totally bemused, like they’d never heard of exemption even being a thing, but I just walked straight in, as I was so pissed off with the whole thing and in no mood to be messed with. I don’t think I will be going to the theatre again, or any other large social venue, not while this medical apartheid is going on. I will not support this discrimination. It is wrong on so many levels, and I hope others will take a stand too, vaccinated or not. We must not comply with this fascist dictatorship.

It is depressing. I think these companies would find that if they do go ahead with their events and place the onus on the indivudual employee to keep themselves safe, most would be willing to join in the festivities even those who have decided to permanently work from home. Perhaps the FT companies just want ( or need) to save money?

I suppose it will reduce the number of embarrassing photos posted online.

Yep those amazing vaccines really worked and made everybody free as a bird!?