This is a slightly modified version of a speech I gave at the inaugural meeting of the Icelandic Free Speech Society on Saturday January 7th. You can watch a video of me giving it here.

In the run-up to Christmas, the journalist Christopher Snowdon posted a lengthy Twitter thread that reproduced the projections of various U.K. modelling teams in December 2021, many of them linked to SAGE, showing a range of outcomes in terms of infections, hospitalisations and deaths the new Omicron variant was likely to result in if the British Government failed to lock down over Christmas. These were, in the jargon of the modelling trade, ‘reasonable worst case scenarios’, or, as the U.K. Health Security Agency put it, “a range of plausible scenarios”.

As Christopher gleefully pointed out, none of these scenarios materialised, even though Boris Johnson held his nerve and refused to impose another lockdown (although, to the consternation of Lord Frost, he did impose ‘Plan B’, making masks mandatory in some indoor venues, access to large venues contingent on a negative test result and advising people to work from home). Not only did these ‘plausible scenarios’ fail to materialise, but the actual numbers of infections, hospitalisations and deaths that did occur weren’t even close to the lowest end of the range.

Neil Ferguson, for instance, told the Guardian that “most of the projections we have right now are that the Omicron wave could very substantially overwhelm the NHS, getting up to peak levels of admissions of 10,000 people per day”.

The U.K.HSA released a report on December 10th that included a model showing daily Omicron infections reaching 1,000,000 a day by December 24th.

In fact, only two million people were infected in the whole of December and hospital admissions peaked at less than 2,500 a day.

SAGE submitted a report, based on the work of its modelling subcommittees SPI-M and SPI-M-O, showing a ‘range of plausible scenarios’ in which deaths from Omicron would peak at between 600 and 6,000 a day.

In the event, deaths peaked at 210 a day.

Christopher’s reason for posting this thread, I suspect, was to encourage people to ignore the drumbeat for another lockdown in the run-up to Christmas 2022. If the doom-mongers had got it so badly wrong last Christmas, why should we take their projections about this Christmas seriously?

But, from the point of view of the lockdown lobby, this wasn’t a knock-down argument. Yes, the infections, hospitalisations and deaths from Omicron at the end of 2021 weren’t even in the lower range of SAGE’s ‘reasonable worst case scenarios’, but that didn’t prove the models had been wrong or that the Government was right to ignore them.

The definition of ‘reasonable worst case’ is not the scenario that will probably emerge if the government does nothing, merely a ‘plausible’ one, if the assumptions plugged into the model are correct – although, to confuse matters, the modellers do sometimes describe the outcomes they’re projecting as ‘likely‘ if the government does nothing, or only imposes light-touch restrictions, as Neil Ferguson and his co-authors did in Report 9.

But the scenarios set out by SAGE in December 2021 were only ever billed as possibilities, not probabilities, so the fact that the actual figures for Omicron at the end of 2021 were far lower than those envisioned by SPI-M and SPI-M-O doesn’t mean their models were wrong.

The job of the modellers is to sketch out a range of ‘plausible’ scenarios in the event of the Government doing nothing, or not doing enough, so policymakers are aware of the risks. That’s why the modellers are so insistent that the output of their models are ‘projections not predictions’.

In the eyes of those clamouring for Boris’s Government to lock down at the end of 2021 – like Independent SAGE, which called for an “immediate circuit-breaker” on December 15th – it was his responsibility to do whatever he could to mitigate the likelihood of the ‘reasonable worst case scenarios’ materialising, even if the probability of that happening was low.

Case in point: Professor Graham Medley, the Chair of SPI-M, said in a Twitter exchange with Fraser Nelson in December 2021 that the outputs of the models were “not predictions” but designed “to illustrate the possibilities”. When Fraser asked him why his models didn’t include more optimistic scenarios, e.g. probable rather than possible outcomes if the Government didn’t change course, he seemed perplexed. “What would be the point of that?” he asked.

In an article about this exchange, Fraser asked: “What happened to the original system of presenting a ‘reasonable worse-case scenario’ together with a central scenario? And what’s the point of modelling if it doesn’t say how likely any of these scenarios are?”

The answer is that, when it comes to these extreme risks, the consensus among senior scientific and medical advisors and their academic outriders is that policymakers should not be asking what’s probable, only what’s possible. As they see it, politicians have a responsibility to safeguard populations against ‘reasonable worst case scenarios’ and if they were to accompany them with less apocalyptic projections – and pointed out they were more likely – the politicians might be tempted to ‘do nothing’.

In light of this, the fact that the Omicron wave in the winter of 2021-22 turned out to be relatively mild even though the Government didn’t impose a lockdown is neither here nor there. It was still irresponsible of the Government not to lock down – at least, in the eyes of the lockdown lobby.

By the same logic, the lockdown enthusiasts are unimpressed when sceptics point to the fact that Sweden had, according to some estimates, fewer excess deaths in 2020 than every other country in Europe in spite of the fact that the Swedish Government eschewed lockdowns that year.

In a particularly candid moment, the enthusiasts might even acknowledge that the harm caused by the lockdowns in the rest of Europe was, in all likelihood, greater than the harm those lockdowns prevented.

The relevant counter-factual here is not what in all likelihood would have happened if European countries hadn’t locked down in 2020 – so Sweden is irrelevant – but what could have happened in a ‘reasonable worst case’ scenario – a projection, not a prediction. Given that European governments couldn’t rule out these scenarios coming to pass, it would have been irresponsible of them not to mitigate that risk by locking down, even though it was foreseeable that the harm caused by those lockdowns would probably be greater than any harm they prevented.

That’s why the British Government believed it was right not to waste time carrying out a forensic cost-benefit analysis of the impact of the lockdowns before taking the decision to lock down, which we know it didn’t. Had it done so, that analysis would have shown that, in all likelihood, the cost of locking down outweighed the gain. (For the benefit of those who haven’t been paying attention for the past 21 months, I’m thinking of the economic harm of shuttering businesses, the medical harm of suspending cancer screenings and other preventative health checks, the educational harm of closing schools, the psychological harm of shelter-in-place orders, etc.)

All that was beside the point, as far as policymakers and their scientific and medical advisors were concerned. The point of locking down was not to avert the likely harm resulting from doing nothing or doing less, but to mitigate the risk of far greater harm that was within the range of possibilities. That’s why there was no point in carrying out expensive, time-consuming cost-benefit analyses. Even if those analyses showed the lockdowns would likely cause more harm than good, locking down would still have been the right thing to do.

Pascal’s Wager

The logic policymakers applied in March of 2020 is the same as that used by the 17th Century French mathematician Blaise Pascal in his famous ‘wager’.

It goes like this: God may or may not exist, but it’s rational to behave as if he does and become a believing, observant Christian, since the cost of not doing so if he does exist and the Bible is true is greater than the cost of doing so. You may think it improbable that God exists, but that’s not a rational reason not to believe in him and obey his commands since the cost of disbelieving and disobeying if he does – eternal torment in the fires of hell – is so astronomically high. Given the imbalance between these costs – given that the cost of not being a pious Christian is higher by an order of magnitude than the cost of being one, just in case God exits – it is rational to adjust your behaviour even if you think the probability of him existing is very low.

This ‘Pascallian logic’ didn’t just inform the response to the pandemic of most Western governments, it’s also the rationale for mitigating the risk posed by climate change.

Just as policymakers around the world thought they were justified in curtailing our liberty on an unprecedented scale in 2020 and 2021 to mitigate risks that were plausible but not probable, so those policymakers believe they’re justified in reining in our freedom to mitigate the risk of catastrophic climate change. The cost of imposing top-down measures designed to curb our carbon emissions – the increase in deaths from cold weather as a result of rising energy bills, for instance – is low compared to the potential cost of not reducing our emissions if the apocalyptic warnings of climate activists turn out to be true.

The analogy with Pascal’s Wager might not be immediately obvious because advocates of net-Zero and other policies designed to mitigate the risk of catastrophic climate change often present their case as if the probability of that risk materialising if we ‘do nothing’ is not just higher than 50%, but close to a 100%. Greta Thunberg, for instance.

Indeed, exaggerating the probability of the most apocalyptic scenarios materialising – and introducing ‘tipping points’ or ‘points of no return’ in the near future, after which the effects of climate change will be ‘irreversible’ – has been adopted as a deliberate strategy, not just by climate activists and climate scientists, but by ‘responsible’ journalists as well. For instance, the BBC reported in 2019 that “one million species” were “at risk of imminent extinction”, a claim based on a report by the UN’s Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). I dug down into that claim for the Spectator and discovered just how tenuous it is. Among other things, over half the species categorised as being “at risk of imminent extinction” had a 10% chance of going extinct within the next 100 years (and even that claim was dubious). As I pointed out, that was like saying that because Manchester City faces a 10% chance of being relegated in the next 100 years, the club is “at risk of imminent relegation”.

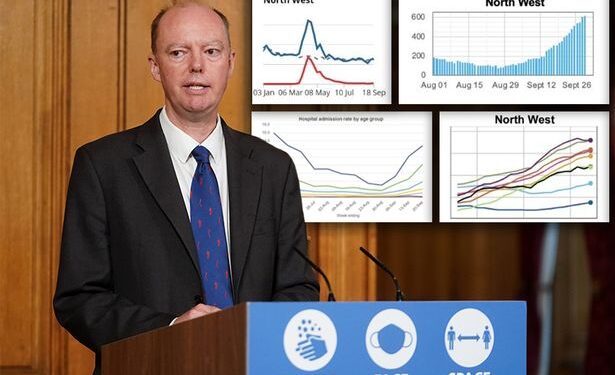

Exaggerating these risks is partly informed by game theory and, in particular, ‘collective risk social dilemma’ or CRSD. Psychological experiments have shown that to encourage individual participation in costly corrective group behaviour – such as purchasing electric cars or investing in renewables – both the scale of the negative consequences of failing to engage in that behaviour, and the likelihood of those consequences materialising, have to be exaggerated. I don’t doubt that CRSD also informed many of the projections set out by Sir Patrick Vallance and Sir Chris Whitty at the Downing Street press briefings in 2020 and 2021.

But we shouldn’t forget that the projections those catastrophising about the risk that climate change poses are relying on are, in fact, ‘reasonable worst case’ scenarios produced by climate models – projections, not predictions. The climate scientists themselves – the more rational ones, anyway – acknowledge that the probability of their models’ most catastrophic projections materialising is less than 50 per cent and might even be as low as one per cent, or lower. These scenarios are plausible, not probable. Nevertheless, they think humankind has a moral duty to reduce carbon emissions to mitigate the risk of the worst scenarios coming to pass – and, indeed, should be forced to do so by national governments, as well as the EU and the UN.

Clearly, this interference in our liberty is informed by the same Pascallian logic – the same aversion to low-probability/high-consequence risks – that underpinned the lockdown policy. Indeed, the debt that climate activist policymakers owe to Pascal was spelt out explicitly by Warren Buffett: “Pascal, it may be recalled, argued that if there were only a tiny probability that God truly existed, it made sense to behave as if He did because… the lack of belief risked eternal misery. Likewise, if there is only a one per cent chance the planet is heading toward a truly major disaster and delay means passing a point of no return, inaction now is foolhardy.”

Climate contrarians like me often point out that the predictions that climate alarmists have made in the past haven’t come true.

For instance, Paul Ehrlich, author of the 1968 bestseller The Population Bomb (1968), told the New York Times in 1969: “We must realise that unless we are extremely lucky, everybody will disappear in a cloud of blue steam in 20 years.”

In 2004, Observer readers were told that Britain would have a “Siberian” climate in 16 years’ time. Temperatures did drop to minus five in December, but we don’t yet have an Icelandic climate, let alone a Siberian one.

Climate scientist Peter Wadhams, interviewed in the Guardian in 2013, predicted Arctic ice would disappear by 2015 if we didn’t mend our ways – in fact, Arctic summer sea ice is increasing.

In 2009, Prince Charles said we had eight years left to save the planet, while Gordon Brown announced in that same year we had just 50 days to save the Earth.

But, for the more serious-minded advocates of policies like net-Zero, the fact that these scenarios haven’t materialised is no more relevant than the fact that the ‘worst case’ projections of the pandemic modellers didn’t materialise at the end of 2021 or that no-lockdown Sweden suffered a comparatively low number of excess deaths in 2020.

These scenarios, they now claim, were only ever ‘reasonable worst case’, not predictions of things the modellers, or the advocates of reducing carbon emissions, thought were likely to happen. And if they exaggerated these risks at the time, that was merely a white lie because a bit of scaremongering is necessary to get people to adjust their behaviour. CRSD.

Free speech

Before talking about what arguments we might use to challenge ‘Pascalllian logic’ I want to mention one more area of public policy informed by this reasoning, namely, curbs on free speech.

For instance, it’s the rationale employed by large social media platforms like Facebook for suppressing the speech of those who question the efficacy and safety of the mRNA Covid vaccines.

Those platforms, or those pressurising them to remove vaccine sceptical content, such as the U.K. Government’s counter-disinformation units, believe it’s responsible to remove that content because they take it for granted that the mRNA vaccines and boosters alleviate more sickness than they cause and it’s possible that not removing this content will increase vaccine hesitancy.

They don’t know it will. Indeed, they may accept that the likelihood of it doing so is quite low. But nevertheless, if there’s a risk the content will cause just one person not to get vaccinated, they believe they’re justified in removing it.

The same rationale is used to license the removal of content questioning the claim that we’re in the midst of a climate emergency – that extreme weather events are caused by climate change, for instance. If it’s possible that such content might discourage people from reducing their carbon footprint – not probable, but possible – they feel justified in removing it.

Finally, ‘Pascallian logic‘ is used to justify passing laws prohibiting ‘hate speech’ or censoring the purveyors of ‘hate speech’, like Andrew Tate. The argument isn’t that such speech will cause violence to be inflicted on those it’s targeted against, such as women and girls, or even that such violence is likely. Rather, the argument is that it’s possible ‘hate speech’ will cause violence. That alone is reason enough to ban it.

In defence of liberty

So, now that we’ve identified that ‘Pascallian logic’ informs the curtailment of our liberty in these three separate but important areas – the three greatest threats to liberty in the contemporary world, I think – what arguments can we make to challenge this type of reasoning? What can we say in defence of liberty?

One place to look is the standard objection to Pascal’s Wager.

One rejoinder is that belief in a supernatural being is irrational (although Isaac Newton and many eminent scientists believed in God), so it can never be rational to modify your behaviour just in case that being exists.

Setting aside whether this is a good argument or not, it doesn’t apply to ‘reasonable worst case scenarios’ since they’re produced by computer models created by epidemiologists and climate scientists. They bear the imprimatur – the authority – of science.

Another line of attack is to point out that the selection by policymakers of what low-probability/high-consequence risks to safeguard against is somewhat arbitrary.

For instance, why aren’t we building expensive defences against the possibility of an asteroid strike or colonising other planets as refuges just in case the Earth is invaded by aliens?

More prosaically, instead of just banning the sale of new diesel or petrol cars in the U.K. from 2030, why don’t we just ban cars altogether? After all, every time you get in your car it’s possible you’ll kill someone, even if it’s improbable.

What’s the rational basis for curtailing our liberty to reduce the likelihood of some low-probability/high-consequence risks materialising, but not others?

The advocates of large-scale policy interventions like lockdowns and net-Zero have an answer to this, which is that the reason for prioritising some risks above others is because if they materialise they will disproportionately effect vulnerable, disadvantaged, historically marginalised groups.

This is the rationale for imposing permanent mask restrictions by an American group calling itself the ‘People’s CDC’, which was the subject of a recent article in the New Yorker by Emma Green. It’s a collection of academics and doctors who are part of a broader coalition of left-wing public health activists advocating for more persistent mitigations.

These activists believe the reason the state has a duty to continue mitigating the risk of COVID-19 is because the virus’s infection fatality rate is higher for disabled people, elderly people and fat people – as well as black and minority ethnic people because, on average, they have less access to healthcare. One of the policies recommended on the People’s CDC website is that all social events should take place outside with universal, high-grade masking. Opposing this policy, the activists argue, is ableist, fatphobic and racist. Lucky Tran, who organises the People’s CDC’s media team, says: “A lot of anti-mask sentiment is deeply embedded in white supremacy.”

Moralistic scientism

You may not take activists like this and their demands for permanent Covid restrictions seriously, but I believe this combination of extreme safetyism and left-wing identity politics is a potent cocktail. Emma Green described it as “a kind of moralistic scientism – a belief that science infallibly validates lefty moral sensibilities”.

This ‘moralistic scientism’ undoubtedly informed the zero-Covid policy in New Zealand, as well as the draconian lockdowns in some Canadian and Australian states, and the pressure to lockdown in Christmas 2021 exerted by Independent SAGE, the British equivalent of the People’s CDC.

One of the organisations that funds the People’s CDC is the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the CEO of which, Richard E. Besser, is a former acting director of the CDC.

Professor Susan Michie, one of the members of Independent Sage, is also a member of SAGE.

According to Emma Green, this coalition of public health activists is “influential in the press”, and that’s certainly true of the Guardian, which published the People’s CDC manifesto last year.

Much of the campaigning for net-Zero and other policies designed to reduce carbon emissions is also rooted in ‘moralistic scientism’. Our duty to mitigate the risk of climate change, these activists argue, isn’t just because climate scientists have ‘proved’ that the consequences of not doing so could be catastrophic, but because the negative effects of climate change disproportionately impact the Global South – or the ‘Global Majority’, as it’s now called.

So what can we say in response to this ‘moralistic scientism’?

One argument is that the policies imposed in an attempt to avert these low-probability/high-consequence risks disproportionately harm precisely the same disadvantaged groups they’re designed to protect.

For instance, when schools were closed in the U.K. during the lockdowns, children from low-income families were much more likely to suffer learning loss than those from middle- and high-income families. They’ve also proved less likely to return to schools since they’ve been reopened. The Centre for Social Justice published a report last year pointing out that 100,000 children are now ‘missing’ from the British education system. The report found that children who were eligible for free school means were over three times more likely to be severely absent than their peers.

Similarly, deindustrialisation policies designed to avert the risk of a climate catastrophe are more likely to harm people in low-income countries than they are people in middle- or high-income countries. Indeed, that was one of the arguments put forward at Cop27 for why the fully industrialised West should pay ‘reparations’ to African and Middle Eastern nations.

Oddly, however, these arguments never seem to land with advocates of large-scale, top down policy interventions to mitigate low-probability/high-consequence risks. The notional harm caused to ‘at risk’ groups if we ‘do nothing’ engages their moral passions far more powerfully than the actual harm caused to those groups by the measures designed to protect them.

Another line of attack is to appeal to the ‘scientism’ of the advocates of these top-down policy interventions, pointing out that there’s no such thing as ‘the Science’ in the sense that very few, if any, scientific hypotheses are ever completely settled, including the claim that global warming is caused by anthropogenic climate change. And even if they were settled, to argue that they ‘prove’ we should implement certain policies would be to commit the naturalistic fallacy – to infer an ‘ought’ from an ‘is’.

Indeed, the Scientific Revolution in the 16th and 17th centuries wouldn’t have been possible if descriptive propositions about the natural world hadn’t been disentangled from the cosmology of the Old Testament and Christian morality more widely.

One variant of this argument is that the reason we shouldn’t allow high-level policy decisions to be based on the projections of supposedly ‘scientific’ models is because those projections are, by definition, untestable. Yes, we can point to predictions that haven’t come true – at Davos three years ago, Greta Thunberg said we had eight years left to save the planet, so the clock is ticking on that one. But the more cautious climate activists will acknowledge that the ‘reasonable worst case scenarios’ they’re warning us about are projections not predictions and when they fail to materialise if we don’t follow their policy recommendations, they can say we just got lucky. In this way, the projections of the models – which are only saying what’s possible, not what’s probable – can never be falsified. As Karl Popper pointed out, if a hypothesis cannot be falsified, it doesn’t deserve to be called scientific.

But, as climate contrarians like me know, those argument also fail to land. Anyone expressing scepticism about net-Zero and similar policies is automatically branded a ‘denier’ – or a purveyor of ‘climate misinformation’ – in the pay of Big Oil.

There’s one final argument I can think of, which will be familiar to the opponents of Big Government, which is to acknowledge that humankind does have a moral responsibility to do what it can to mitigate low-probability/high-consequence risks, particularly those that will disproportionally affect historically marginalised people, but point out that policymakers simply lack the competence and expertise to mitigate these risks.

Ignorance, as well as the law of unintended consequences, means that even if we’re concerned about these risks, we simply cannot be confident that the costly measures policymakers are proposing will make them less likely to materialise.

For instance, the lockdowns and other Covid restrictions didn’t merely fail to reduce the spread of COVID-19 in those countries where they were imposed, they left populations more vulnerable to seasonal respiratory viruses, such as the winter flu strain that’s currently putting the NHS under pressure.

Encouraging people to scrap their existing cars and buy new electric ones may not result in any net reduction in carbon emissions since the carbon emissions resulting from the production of a new car are so much greater than those produced by continuing to drive a ‘wet’ car, at least within a 10-year period.

For a discussion of the incompetence of policymakers see ‘The Problem of Policymaker Ignorance’ by Scott Scheall, who also has a Substack newsletter and podcast.

But will that argument land? Won’t we be accused of making the same old, tired libertarian arguments, probably in the pay of rapacious corporations who want to avoid state regulation?

Greatest threat to our liberty

I think this new hybrid of extreme safetyism and left-wing identity politics – ‘moralistic scientism’, in the words of Emma Green – will be the greatest threat to our liberty in the coming decades and resisting it will be hard. I’m reluctantly coming to the conclusion that trying to persuade its adherents to be a bit less alarmist and a bit more reasonable by appealing to evidence and logic is misguided. They may claim to be ‘following the Science’, but they don’t set much store by the scientific method.

The reason these arguments don’t land, I suspect, is because ‘moralistic scientism’ is a synthesis of what might be described as the two fastest-growing religions in the West – the woke social justice movement and the green, climate activist movement. It now has child saints (Greta Thunberg), missionaries (George Monbiot), high priests (Sir David Attenborough), annual evangelical meetings (Cop26, Cop 27, etc.), catechisms (‘There is no planet B’), a Holy See (the IPPC), and so on. For the votaries of this new cult, it provides them with a sense of meaning and purpose – it fills the God-shaped hole left by the ebbing away of the Christian tide.

Therefore, to successfully resist it, we need something more than rational scepticism. We need a new ideology – something like a religious movement of our own. One that’s more optimistic about the future of humanity, that places a little more faith in the ability of people to do their own risk assessments and voluntarily adjust their behaviour if necessary. One that keeps faith with the principles of democracy and national sovereignty and opposes the transfer of power from national parliaments to unelected international bodies who are convinced they know what’s in our best interests. An ideology that recognises the limits of science when it comes to informing public policy – particularly computer models. That restores public trust in science by disentangling it from ‘moralistic scientism’ and depoliticising it more generally, making it clear that science can no more be invoked to support left-wing policies than it can right-wing ones. Above all, a movement that places free speech and the unfettered pursuit of knowledge at is core. A second Scientific Revolution. A New Enlightenment.

Creating that, I believe, is the greatest challenge facing those of us who want to resist the creep of this new authoritarianism.

Stop Press: Steven Pinker has published a speech he made in November at the Stanford Academic Freedom Conference that is partly about how to deal with the problem of science becoming politicised and the resulting decline in public trust in science. He comes at the problem from a different political direction to me, but some of his conclusions are remarkably similar.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

2023 is the year of the ‘polycrisis’, according to the WEF. Or should that be ‘polypsyop’?

”And what is the WEF’s “solution” to the very polycrisis that they created?

Or about 100% manufactured by the well over 80% “global leaders.”

In other words, according to the WEF the only answer is more of the same unelected and installed “penetrators”ushering in their hypercentralized One World Government dystopia.”

https://www.2ndsmartestguyintheworld.com/p/2023-year-of-the-polypsyop

Honestly, their bullshit percentages don’t mean anything, they’re just the saliva flecked rantings of a megalomaniac. All of these ‘crises’, taken one by one, can be dissected and shown for what they are as you say – manufactured – in order to create the conditions ripe for the One World government. You couldn’t make it up!…er…actually…

The Mail again doing its best to induce another virus scenario , nicely timed leading towards May when the who (I’m not using capitals for that twisted shower) will I’m sure get their Global health power treaty ratified . Tedros is now joined by our very own Farrar & Michie “ Let the good times roll “

“Killing pet cats”: I did actually worry quite seriously about the safety of my cats in April 2020, when the “cats spread the virus” myth started, as by then we had all seen how so many people had total faith in Saint Boris’s lies, and handed over all their rights on a plate, begging for him to take even more from them. I was far more worried about the public believing everything the government said, than any mythical danger posed by a virus. Probably one reason the cat cull did not happen is that the government would have had to send executioners into people’s homes to do this, which would have clashed with the “nobody must see anybody” commandment, and said executioners might have been killed by angry cat owners, who would of course be at home, on Saint Boris’s orders. Perhaps the government knew they would never be able to get enough vets onside.

“Boris Johnson must take credit for not locking down for the Omicron variant”: Oh yes, give him a medal, as well as the £5 million he has allegedly earned since being PM, which was probably his only reason for becoming PM: he wanted the glory of it, and none of the work. It would have been better if he had resisted the calls for the first, second and third lockdowns, if he had made his trademark “I do things my way” into the decision not to copy the rest of the world. He would be far more respected now. Poor diddums, it’s a shame he never got the chance to stand at his podium and make a big announcement about the end of restrictions, because the spin machine was then all Ukraine, Ukraine, Ukraine.

As for the Whatsapp messages: we need to be sceptical about this. It may be a double-bluff, a deliberate leak (haven’t we seen those before?), a stage-managed scandal, a damage limitation exercise, possibly planned three years ago, to make us angry about what might have been, so that they can say “we should have locked down harder, faster, longer”, and we are breathing a sigh of relief that they didn’t kill our cats, that all those who were in government are now out, having been replaced with more compliant puppets. I find it very hard to believe that killing cats was ever a serious consideration; this has “deliberate leak” written all over it. The spin “we didn’t know how bad the virus would be, so we had to lock down” is as clear as daylight here, and is probably the first in a long line of other things they “might” have done, so that we thank the Devil for not doing these things.

It all smacks of useful idiots being fed their lines by the stage prompter.

They killed the cats and dogs in the 1660s too, thereby helping the rat population. Nice to know we’ve moved on from such superstitious nonsense.

I still remember that bloody dreadful event in Australia where they shot the dogs in the animal shelter rather than have people travel over there to take them home. Because ‘public health’! Absolute sickos. What sort of a psychopath do you have to be to even consider doing something so evil?

There was similar madness on show during the foot and mouth outbreak of 2001. Locally, a man with a rifle dispatched a small herd of ‘contiguous’ sheep in an enclosure. His aim was poor but he was determined, and randomly fired at the poor beasts running about in panic until he had either killed them, or disabled them enough to stop running so he could administer the coup de gras. There was no penalty for his cruel actions.

I believe if the government had said to kill all cats, a large amount of covidians would have done the job for them, with local ‘seek and destroy’ groups set up to ‘keep us safe’. Sad to say, despite attitudes cooling a bit, I still think it wouldn’t take much to whip up a certain portion of the population into a similar hysterical response.

Having said that, the cat story is a very good psy-ops line to keep the population worried and anxious, isn’t it?

“… Saint Boris’s lies,”

They weren’t his. The populations of nearly all sovereign nations became entrapped by the WHO (CCP) narratives that were propagated using lurid imagery from China and northern Italy. With populations made suitably petrified and therefore suggestable most governments went along with what their citizens demanded – ‘lock me down harder, Boris’, or whoever. Opposition parties complained that Boris was not severe enough. This was all driven by Master Tedrous at the WHO and the CCP.

Kate Wand put together an excellent expose of Fauci and his relationship with the CCP. It is a conspiracy and it’s not a theory. In this video Chinese Professor Zhong Nanshan asserts that economies must not open up until everyone has been vaccinated which may take 2 to 3 years (Fauci agrees), while China was fully open and has not vaccinated it’s entire population. ‘Prof’ Nanshan goes on to say natural herd immunity will not work because it is unscientific and inhuman.

Evidence here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cb-JExoBhmU&t=36s

“Humza Yousaf says trans rapist Isla Bryson should have right to self-identify as female”

So, don’t ditch Nichola Sturgeons gender laws just because of one bad egg?

What a tit! Has he learned nothing?

If you look closely you can see sturgeon hand up is back controlling him!

Come on Scotland, don’t fall for more of this shyte again!

He is a massive Cuckoo in Scotlands nest !! How is he even there ?? Robert The Bruce , Haggis , Porridge , Kilts , Bagpipes , Archie Gemmill & now this anti British SH1T house is going to front their politics

A legislator with blind loyalty to an ideology, zero understanding of nuance and the inability to perceive cause-and-effect doesn’t deserve to occupy this position. This guy needs taking down several pegs

“The UN Discusses Darkening The Skies to Combat Climate Change”

And what God has given them the right to darken my part of the sky?

There’s actually some Hollywood film that is about darkened skies but that is because the Sun is dying not because of an idiot attempt at darkening our own skies in the belief that it would make a difference. It’ll just spread nano-particles all over the world and we have no idea what they will do. The ideas just get more and more ridiculous. Who are these scientists who suggest such things? More importantly however, who are the people who take the scientists seriously? Is there no common sense and balanced thinking going on in the UN corridors?

“Bird flu has mutated to infect people

Thankfully its not something us blokes need to worry about…

Of course it has. The assault is relentless – swine flu, avian flu, goat flu, dog flu, guinea pig flu, chimney flue…. Once the WHO gets its treaty signed, they’ll be able to dictate the response. That must never be allowed to happen.

With respect, I think you missed the word play on ‘Birds/Blokes’.

I agree we can see where this is going and I for one will not be playing along with anything the WHO says must happen. I do expect that our so called government will sign up to this horses arse of an agreement.

No, Neil, I totally got it but I was responding to the headline not your joke.

WHO flu!

Yeah, watch out for the manflu

Worth a watch – we need more kids like this.

https://www.bitchute.com/video/hmfuRhMJbTbY/

Toby says there was no plandemic. This is Robert Malone’s testimony:

The blocking of “early treatment” and/or “drug repurposing” as well as advocacy for genetic vaccines which were presumed (without adequate testing) to be “safe and effective” was supported by an aggressive, harmonized global censorship and propaganda campaign, with significant funding (~US $10 Billion) provided by the US Government.

In addition to US and global suppression (notably except in Mexico) of the prompt use of known (often off-patent) drug therapies to treat the respiratory symptoms of COVID-19 disease, and the disproportionate emphasis on genetic vaccine development and deployment, a number of other counterproductive actions were taken in the name of public health. Most or all of these were modeled after measures implemented by the CCP in China. In many cases, these actions were previously not recommended by the WHO or national health authorities, but these policies were changed in response to the fear of COVID-19. These included arbitrary “lockdowns”, prevention of public assembly, mandated use of particle masks which were neither effective nor designed for preventing viral transmission, arbitrary six foot “social distancing” policies, school closure, alterations in normal medical procedures (diagnostic testing and evaluation, elective surgeries), travel restrictions, vaccine passports and tracking, and many other related procedures justified as advancing “public health” objectives but which were not supported by established scientific evidence.

Much of the national US and global response was managed by the National Security apparatus and Department of Defense of the United States, acting together with the Department of Homeland Security, and these activities included a massive propaganda, psychological operations and censorship program which acted as part of a globally harmonized program in coordination with the World Health Organization, GAVI, CEPI, CDC, EMA and the BBC-Managed Trusted News Initiative to restrict public access and counter any information different from the WHO-approved narrative regarding SARS-CoV-2, COVID, drug treatment protocols and vaccine safety and efficacy. Distribution of any information contradicting official WHO or CDC messaging was deemed mis- dis- or mal-information and defined as potential domestic terrorism. The US Government, and many separate US federal agencies, coordinated closely with WHO, large technology and social media companies to censor and control all information concerning virus, drugs, and vaccines.

On top of a whole series of exercises simulating a globally coordinated response to the ‘next pandemic’ (Event 201 being the last) which Toby ignores, the above is powerful evidence that the governments did not merely take decisions on the hoof, uninfluenced by advisers who after 20 years of simulations already had a script to follow.

….agreed Steven..the withdrawal of treatments, of all kinds, is one of the most egregious things to have happened during the con..and I believe it cost many people their lives……they knew when they took HCQ and Ivermectin from the shelves in the US, that they could be used for treatment..

This study from 2005 shows that chloroquine is a ‘potent inhibitor of SARS’…

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1232869/

The fact that the study had been ‘fact-checked’ many times during the scam, tells me that they knew about it from the start and tried very hard to discredit it…

As an aside at least two people I know have recently had letters from the NHS telling them that they’ll be receiving testing kits as ‘there are now treatments for Covid-19 that can be prescribed” should you get Covid!!

Both of these people have had cancer in the past, but both are fit and well..and unvaccinated….

The treatments are Paxlovid, Veklury (Remdesivir), Lagevrio (Molnupiravir) and Xevudy, a monoclonal antibody……

As far as I’m aware, all new, and all experimental, with few studies, and no long term safety data…and in some cases some well known serious side effects.

My two friends are on the ball, but how many more will be suckered in?

Related to digital pound, on the two petitions to the House of Commons being looked at on Keeping Cash, they have commissioned a Survey on Acceptance of Cash. This must be completed by 10am on Thursday 9 March, but is very quick and easy to do. My including a link is likely to result in whole message being censored, but the link is available through yesterday’s UK Column News, being the last item on the topic of Parliamentary Petitions in the Summary

The first petition (making it unlawful for shops top refuse cash) is closed. The second one requiring businesses and public services is still open. The link is here: petitionDOTparliamentDOTukSLASHpetitionsSLASH622284 – .’s and /’s obviously

Lori Lightfoot has failed in her bid to be re-elected as Mayor of Chicago. I like to think her attitude and policies towards those who declined the gene therapy injection might have had something to do with it.

https://twitter.com/chicagosmayor/status/1473382110576594948?lang=en

Revolting person. I will be celebrating the news later.

She’s that really weird looking woman isn’t she? I’m going to sound like a bitch but her face doesn’t suit her name…I can see why the Americans call her ”Beetlejuice”.

She’s a real sinner.

Loved this reply…

Can you please do something about the murder rate instead? Thank you.

We’re tired of your gaslighting, fascist, bullshit: targeting individuals who have naturally-acquired immunity & who don’t want a jab that doesn’t confer immunity, & want to be left alone.

Merry Christmas

seems fair to me!! LOL!

“Natural immunity”

“Covid vaccines”

You can only charge for one of those “cures”

Babylon Bee’s take on the next Pfizer press conference: –

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FsQjnv9Dwco

Do electric cars know the weight they are carrying? Do they adjust their distance parameters depending on whether/weather the car has four people and luggage compared to,. one person?,seen in most ev car ads?.. I did asked Toby this for a fiver but he was about to go on TV! an article about electric cars, so he didn’t have time to answer my £5 question! SO, can evs replace internal combustion vehicles like for like? !

!

Capacity was a seller once upon a time! spacious boot, leg room, visibility, power, enough for the wholesome family

What ever happened to the real meaning of a personal transportation system?

A car, personal,

Freedom!

How did it turn into limited? Close? Near? 15 min city?