It is now pretty much consensus that the sanctions on Russia have failed. Yet their failure was extremely predictable. Why did Western policymakers think they would work? It appears that they did not undertake a realistic economic analysis. The invasion caught many by surprise, to be sure, but this doesn’t excuse policymakers from not gaming out a sanctions scenario beforehand.

At a macro-level it is not hard to show that the sanctions have failed. You can look at Russian GDP projections from the IMF for 2022 which see the Russian economy contracting by 3.4% – a far cry from the ~50% decline President Biden promised us. Or you can look at falling Russian inflation and interest rates – and compare them to rising inflation and interest rates in the West. Or you can simply look at the looming energy crisis in Europe. Whichever way you cut it, the macro failure of the sanctions is clear.

But what about the micro level? Many Western companies ceased doing business with Russia, which means the structure of the Russian economy will have to change dramatically. One of the most publicised Russian responses was their creation of an alternative to McDonald’s called ‘Vkusno I Tochka’ which translates to ‘Tasty and That’s It’. The company simply cannibalised the restaurants and supply chains McDonald’s was using and changed the name on the sign. Since then, the company has apparently expanded into Belarus.

It was not hard for the Russians to rebrand McDonald’s outlets within the country and keep them operating. All they really lost is the brand. But what about an industry that requires manufacturing and engineering? That should be far more difficult to ‘substitute’ than a restaurant chain. Let’s look at the Russian car market in detail to get a sense of how it has been impacted by sanctions.

The first question to ask is: are Russians unable to buy new cars due to the sanctions? There are plenty of headlines about huge contractions in the Russian new car market, but they are obviously misleading. Why? Because the Russian economy has fallen into recession since the invasion. So some of the contraction of demand for cars is simply due to the larger economic contraction.

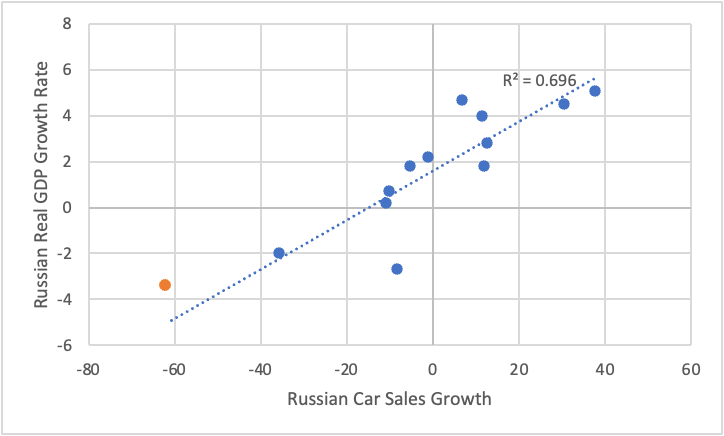

Let’s analyse this properly using regression techniques. Below is a linear regression of real GDP on car sales growth between 2010-21. An estimate for car sales growth in 2022 together with an IMF estimate of real GDP growth is included – the orange dot.

What we see is that the orange dot largely ‘fits’ the regression line. This means that some of the decline in car sales is likely due to the recession. But because the dot sits above the regression line, we know that the fall in used car sales is somewhat higher than would be expected from the projected fall in real GDP.

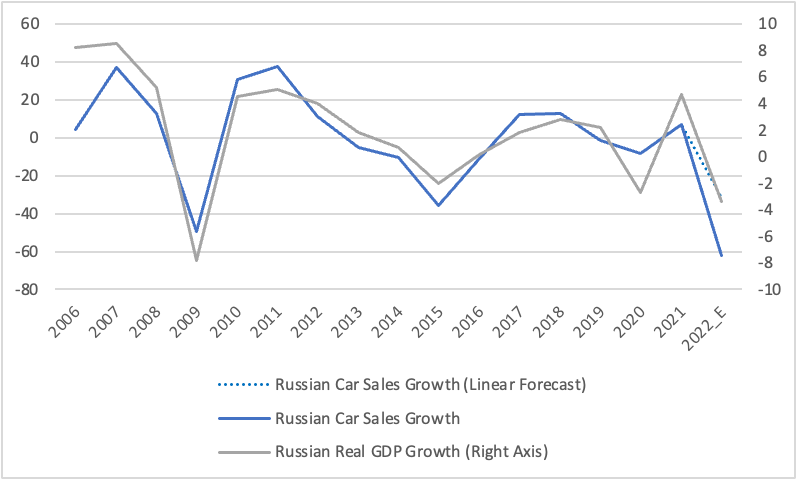

We can use this regression to ‘forecast’ car sales growth based on the relationship between real GDP and car sales growth, given the projected fall in real GDP. And we can compare this to the actual decline in car sales growth.

Here we see the regression predicted that car sales growth would fall around 31% for a 3.4% contraction in real GDP. But the actual fall we saw was around 62%. So we can conclude that around half of the decline in new car sales in Russia was caused by the recession and around half was caused by sanctions targeting the car market.

This fits with some of the more reliable news reports from Russia. For example, Reuters reports that President Putin has admitted there have been some disruptions in the Russian car market and has suggested price caps to ensure that Russian carmakers do not take advantage of the shortage of cars to gouge Russian customers. The head of Avtovaz, one of Russia’s leading carmakers, said the industry had “never before faced such a large-scale and comprehensive challenge”.

How do we evaluate the roughly 30% decline in car sales that we can attribute to the sanctions? As the Russians themselves admit, it has undoubtedly introduced challenges. But a 30% decline is, on balance, not that bad – especially considering that we are not even a year into the sanctions. It seems likely the Russians will get the market for new cars back on track within a year or two.

So one-third of would-be new car buyers will have to delay their purchases for a year or two. Inconvenient, but hardly a nation-destroying crisis – and far less onerous for the average Russian than the energy shortages Europe faces over the next two years.

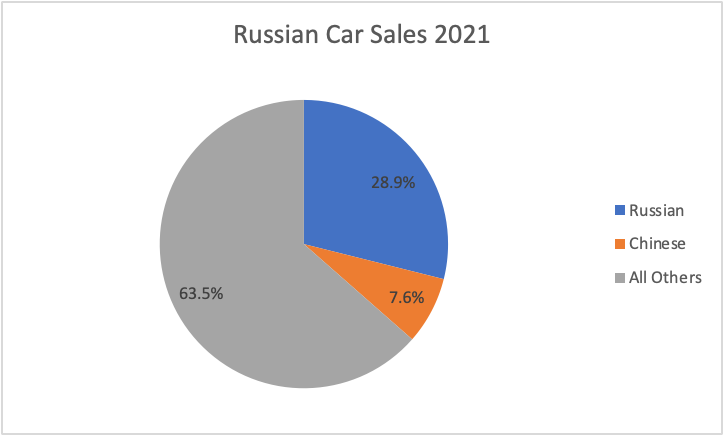

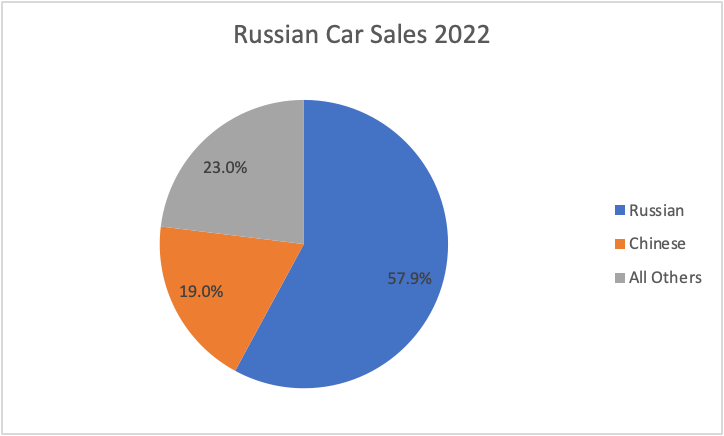

What about long-term changes to the composition of the Russian automotive market? This, I would argue, is far more interesting to study. As the multipolar world emerges, the changes Russia sees to its automotive market may provide a template for many other countries. The two charts below show the percent of cars sold in Russia that are of Russian and Chinese origin versus the rest, in 2021 and 2022.

Sales of Russian models have increased enormously, doubling as a share of the total and now making up more than half the overall market. The Chinese share of the market has also tripled and now comprises almost a fifth of the total; Chinese models now compete with all other international models.

What Russia is showing is that a country can have a relatively functional car market without relying on Western and Western-aligned car manufacturers. In the coming years, it seems likely that Russian car shortages will cease. But unless something dramatic happens, it seems unlikely that Russians will start buying large quantities of international models again.

By 2030, there is every chance that the car markets in other non-Western countries will look more like Russia’s car market in 2022 than Russia’s car market in 2021. Once again, we see that the sanctions imposed on Russia are self-harming.

In the 1990s, the West used to see its economic influence in countries like Russia as a victory and a show of Western power. This was always the correct view. Now our leaders see the exclusion of Western products from foreign markets as a victory. This is such a muddled view it is almost comical. It is the sort of view that shows how ill-prepared our leadership class are for navigating the new multipolar world.

Philip Pilkington is a macroeconomist and investment professional. You can follow him on Twitter here and subscribe to his Substack newsletter here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

A bit of a one sided contest when TPTB hold all the cards and as Tony Blair indicated all the people are in place.

Exactly and the timeline trail to where we are now… goes back to at least 2012.

Back in then the NIH held a conference to gauge the temp and discuss the funding of questionable GoF research work on HPAI H5N1 flu viruses, here are some choice panel Q/As

https://youtu.be/ZdTRIgrgmn8?t=4948

https://youtu.be/j6_qPZm9bNM?t=3864

https://youtu.be/4fsVN34LRb8?t=6828

https://youtu.be/Gnhb9-qjM-4?t=5653

https://youtu.be/j6_qPZm9bNM?t=1670

And yes Fauci was a key player/driver in extending the validity of gain-of-function in this particular conference opening.

https://youtu.be/BACqqgRpktA?t=854

So how did the NIH almost a decade later fund the controversial bat flu virus work, via the back door and ECOHealth Allance of course farming the work into the Wuhan Institute. This lab operated outside of western legal jurisdiction and frameworks, and pushed the research at just BSL2 level?

Nothing to see here folks… move along… move along.

Nuremberg Trial 2.0 is needed right now and we need an immediate stop to these compromised and useless clot shots.

The timeline trail of where we are now goes back to the Russian Revolution – and even way back further than that.

Via the Frankfurt School who fled Nazi Germany to set up shop in America.

Back to the highly unusual and improbable mutation in wild grass plants that took place at the end of the last ice age, around 14-12k bc, in a very small corner of the world, the so called “Cradle of Civilisation”/”Fertile Crescent” in the Middle East, and nowhere else, which gave rise to the largest protein molecule that we ever eat, by far, which is gluten, present in wheat, rye and barley, and which contains an opioid.

Almost as soon as this mutation occurred the humans in that very small part of the world invented agriculture; they started sowing and harvesting this opioid-containing plant, putting in backbreaking hours of work, building fences and storage facilities to protect the opioid-rich seed/grain and permanent, rectangular houses around that to live in.

They also simultaneously invented religion/gods and built temples etc.

This period of unusual behaviour ( from the previously nomadic hunter-gatherer to the settled farming lifestyle ) is known as the Neolithic Revolution. We have never recovered. We’ve been addicts of one sort or another ever since.

We’ve been addicts of one sort or another ever since.

We also shrank after abandoning hunter gathering, only recovering our normal size after the industrial revolution saved us from agricultural enslavement.

I don’t believe there are many critical thinkers now. Most prefer to learn from the internet, and one view is more than enough, so the loudest narrative is the winner. . The behavioural psychopaths have worked well, but not just with covid. Climate change too, we have one of the most benign climates in the world, yet, they give heavy rain or wind a Name now! They have actually persuaded people that the climate in the UK is changing into an unmitigated disaster zone if we don’t do something soon.

Even those who go to the internet are probably more informed than those who just watch one media outlet on the tv – as at least there’s always associated comments to posts online which argue both sides of a narrative.

My mum is the biggest example of this going, if sky news told her that the sky was green today – she wouldn’t look out her window to check the truth behind this, she would just blindly believe them and then probably tell all her friends about it

I agree, got relatives who are the same with the BBC, I get well the ‘bbc said’ all of the time. The internet is a good source of info but I bet most don’t delve, they seem to see an answer and stick with it.

The rest of the world used to similarly rely on the BBC World Service but recognise now what a shallow version of itself it has become so switched off in droves.

Shame its home audience don’t realise the same for its domestic output.

The home service is even worse than the world, the world service goes out all over the world and they have to be careful how big a lie they dare tell, they mostly simply omit discussing inconvenient stories. The UK services know the viewers/listeners don’t see different pictures of the world around them so can tell much bolder untruths.

When out and about as a key worker during lockdown proper I used to listen to R4 8-10am for the news, Today and daily magazine discussion programme.

Once confirmed in my scepticism I found their bias and one sidedness laughably easy to spot.

Jeremy Vine on R2 in the afternoon was a little more difficult as he did try to push the boundaries now and then.

MK Ultra wasn’t stopped because it failed but because they figured it out

Mind Games, covid will go the same way

First they fool you with covid, then climate change. The next thing they will say is the earth isn’t flat!

Covid is real, the only lie is that totalitarianism somehow helps handle it, climate change is real, the only lie is that handling it should require changes to ordinary people’s lives (convert all on-grid energy to nuclear and renewables, switch steel, concrete and fertiliser production to emission free processes (energy intensive but with all that nuclear you’ll have energy to spare), put a hydrogen pump at every petrol station, offer a prize fund for developing a hydrogen powered airliner or switch those to carbon neutral biofuel, with this done the market will solve everything else), the earth is quite spherical (technically an oblate spheroid with an equatorial bulge). We have landed men on the moon, and most vaccines (that is to say not the covid ones) do work to stop transmission of disease.

“

mostsome vaccines”‘most vaccines (that is to say not the covid ones) do work to stop transmission of disease.‘ That’s still debatable. There’s plenty of evidence to suggest that many of these diseases were due to environmental poisoning. Polio and DDT for example,. I know plenty of people who have never been vaxxed and have very robust immune systems, including my ex now aged 60. Her GP advised her against all vaxxes because of a severe asthmatic condition. She has suffered from chronic respiratory infections from time to time, now all but gone since I suggested a daily intake of 4000iu of Vitamin D..

Smallpox, around since ancient times as a worldwide mass killer was eradicated by vaccines late last century.

Interesting question.

Smallpox vaccinations were mandatory roughly 1855-1895 in the UK (wikipedia has the details), but that stopped because lots of people refused them (belief that vaccination drives created terburculosis outbreaks, also “serum sickness”, this belief was held by many in the medical and scientific community at the time). After 1895 the rate fell off and there was never again any mass vaccination, yet Smallpox still disappeared.Why? One suggestion is that Cowpox actually was a Smallpox variant, became endemic and outcompeted Smallpox. Or, maybe, living conditions and general public health improved to the point where nobody had any problems (a bit like Scarlet Fever has disappeared).

So maybe the vaccines eradicated it world-wide, but in the UK? Good question.

I read that measles mortality is massively reduced in those with good diets containing plenty of Vitamin A. I wonder if Smallpox was equally linked to dietary deficiencies of a certain place and/or era.

Then surely it should still be endemic in the many shitholes of the world, from Yemen to the favelas, Afghanistan, any refugee hellhole and the Indian slums? Where has it gone as these people have neither goods diets nor sanitation?

Very much this ^^^^

”covid is real….climate change is real….we have put men on the moon ….most vaccines work to stop transmission of disease”

you forgot 9/11 truthers are conspiracy theorists

Do you have data for this???

Plenty on this site and in the wider world would vehemently disagree on some or all of these assertions.

This is the point, all the prevailing narrative is accepted as a base line and then mitigation is offered…….rather than confront the underlying issue….TPTB need to provide the sound data and reasoning for their decisions, with counter argument and debate…. but this was never going to happen. That was what was underestimated….

and now lather, rinse, repeat

Cov-Sars-2 virus may be real, the disease/effect called covid-19 is nebulous, no idea if its caused by the named virus or something completely different, probably sometimes yes, sometimes no.

Climate Change is real, its been happening since the formation of this planet. Is man causing CO2 increases in the atmosphere that endanger the planet eco-system? Absolutely no proof. Has the atmospheric level of CO2 been higher in the past? Yes many times, sometimes 10x or more. Were there humans around at the time? Not often. Is the planet ‘average temperature increasing? According to the best measure we have from the satellites, not for 25 years. And before then average increase was a function of slighty higher minimums, not increases in maximums. Is there actual recorded increases in ‘extreme weather’ events?No, just lots of selective stats which ignore anything over about 20 years ago.

Given the above would a sane person a) get injected with an experimental gene therapy and/or b) throw away a perfectly good gas boiler ; NO!

Which of course is why governments are trying their best to turn the majority of their populations slightly insane.

There’s two diametrically-opposed attitudes concerning internet vs. broadcast media as sources of information.

On the one hand, there are those who can’t particularly see a motivation behind lying or misleading the public, therefore anything coming across official channels must be sacrosanct. And although there is a chance that that is true at face-value, the reality is that coverage is extremely narrow, and only approaches a topic from one angle, hence obfuscating its contest and rendering the content misleading. But this group of people cannot see this fatal flaw in using, say, the BBC to inform one’s general worldview, and see the internet as purveyor of misinformation, the forum for any given nutter, or the arena where the current “infodemic” is playing out.

On the other hand, the second category of people believe that, along with the championing of diversity in race, religion, gender, etc, it follows that informational diversity has its merits too. Diverse information sources contribute to an overall synthesis of ideas, and diversity of opinion comes together to settle on what is likely to be closer to the truth than the single, myopic narrative that is peddled over our “telescreens”.

The main reason the establishment narrative got so firmly cemented in people’s minds was that those pushing it knew what they were doing. SPI-B’s team of behavioural scientists knew exactly how to ingrain the notion of “wear masks to save Grandma”, or “get vaccinated for the benefit of others” into our subconscious belief-systems.

However, with internet at most people’s fingertips, even the laziest research can turn up material that casts doubt on the validity of these implorations.

I always offer the information that the summers were so hot in the fourth century that the Romans grew grapes up in Northumberland from which they made wine. Generally, though, I just get a blank stare, because people don’t bother to process information they’re not interested in.

“I’ve revisited the theme of why lockdown sceptics lost the argument – and I say this in spite of believing another national lockdown in England is quite unlikely.”

We lost the argument (if you want to put it that way) because every powerful institution on the planet got behind the Big Lie from the start, egged on by the world’s second most powerful country. And they outspent us on propaganda by a factor of thousands or millions. No contest.

TY, we are still locked down, in the grip of the folly and evil that is Covidianism. We did not win, we lost. It will take decades, at least, for the Big Lie to be exposed for what it is. The war continues.

Keep buggering on!!

Exactly. And there will be more cutting and pasting of history like this.

The War continues, as you say Julian. Imagining this is a debate is rather like thinking of writing a thoughtful letter to the editor of the Völkischer Beobachter. We must debate as we must continue to argue for our civilisation’s pillars of fossil fuel use, the inventions of the 19th and early 20th centuries, and above all free speech and humour.

But the fight was taken onto the streets early on. And that’s where it must continue.

The same powers that made sure Jeremy Corbyn got nowhere near Downing Street.

It was Jeremy Corbyn and his policies that made sure Corbyn never got near downing street.

Well, not entirely. Had it not been for the machinations of the Labour Party head office in 2017, Labour would probably have won that election. Would it have been better than having another round of Whig/Tory control? Doubtful. The so-called “Left” has been all about MORE lockdowns EARLIER and LONGER and nothing actually innovative. But ironically, we have taken a huge step in the direction of Chinese-style Communist Totalitarianism under the banner of the “Conservative” Party that would probably NEVER have happened under Corbyn.

I think a more convincing argument to explain the failure of many people to respond to logic and reason is the one put forward by Prof Matias Mesnet – that about 40% of the population have been effectively hypnotised by the 24 hour propaganda and are actually comforted by there being an “enemy” out there to focus their anxiety on and being part of a big group fighting that “enemy”. It has given their lives purpose and, ironically, eliminated a lot of the unconscious anxiety they felt pre-COVID. And they don’t want to go back to their pre-COVID purposeless, isolated, anxious existence.

The full interview with Reiner Fuellmich where he explains how “mass formation” works is here:

https://www.bitchute.com/video/RIzxcU8nBYQX/

The solution, he says, is not to batter people over the head with facts and data, because it wasn’t facts and data that took them into their hypnotic state. But rather wake them up by asking them open questions, using humour and satire and cause them to start questioning things for themselves.

The analogy that I use is that of a Derren Brown set-up. How many ‘victims’ of those would have denied that they would succumb?

This is exactly right. I’ve watched all the Derren Brown shows, and seen him live, and his methods are what the Government is using now, on a mass scale. Because I watched his shows and read all his books, I was aware of the techniques when they were being used by the government’s Nudge unit – maybe why the propaganda has had no effect on me.

Hypnotic techniques have never worked on me, and I’ve always been interested in understanding why they don’t.

But then, to me, the idea that the emperor ever had any clothes is a preposterous notion.

They’ve never worked on me either. I’ve been to four different hypnotists over the years with no results. But then, I have a natural suspicion of authority; propaganda washes over me, as does advertising. I’m also very intuitive, if that means anything, and my brain is always on the alert – like when they told me there was a dangerous covid pandemic….

Funnily enough I had intended to go and watch Derren Brown’s live show here in Brum tonight, but the theatre (The Alexandra, happy to name and shame) is requiring proof of ‘covid status’ to permit entry, so I am boycotting as I refuse to show papers for a night at a theatre. I found it somewhat amusing that most of the stuff that you can learn from the man about human behaviour/psychology can be applied to what we’ve seen over the past however many months as you rightly say Mr Dee, now I can’t even go to watch his of all people’s show without being ‘nudged’ by the very same behavioural psychology I no doubt would’ve learned more of were I going

You hypnotise a small section of the population who become rabid fanatics, and then a good chunk of the rest of the population go along “to avoid upsetting anybody”.

What you end up having to do is a full cult member deprogramming exercise.

Here’s my latest contribution to the humour and satire fund.

Does this meme make Dan’s ego look big?

I think it might have been Mesnet that said it, but I remember hearing that the collectivism etc means that all the coronabollocks has essentially become part of people’s identity now because they’re so heavily invested. Therefore when you criticise, or show scepticism etc the Covidian perceives it as an actual sleight on their identity, the same way a religious person does, and therefore reacts very badly, or with hostility, and desperately try to cling on to their belief etc. Thus, as you say it’s probably not facts and data which will win the argument, in the same way facts and data don’t work to convince many religious adherents to question their faith.

As children we’re told to ask questions, yet do this as an adult and you’re a conspiracy nut.

Unfortunately it’s easier for people to believe everything the government says, in the hope it will make all this go away – rather than critically think for themselves and look at what they know, not what they’re told. Like anything in life, being spoon fed is super easy and convenient but having to do something yourself is much harder – it’s no different for people taking in information and looking at cold hard facts either.

A big issue I’ve found is the short attention span people now have as a result of social media and 24 hour rolling news full of soundbites.

I have a group of friends who I’ve known for about 30 years now. I am the only one of them who is not on facebook or Twitter and does not have a TV licence. While debating the COVID issue with them I would write long detailed well thought out arguments and they would simply not read them to the end (and these are people I’ve worked with who I know were perfectly capable and willing in the past to read and write long emails and documents).

People have simply lost the ability to concentrate or think about issues in any depth. Even intelligent, diligent professionals.

Feel your pain, real. I’m not on any formal social media, not have a tv licence (or even a tv at the mo) and I’ve noticed how low people’s abilities are, to maintain a conversation before changing it mid sentence into something less complex. Many of my friends don’t even grasp the seriousness of the situation we in right now. None have any idea of what is going on in government behind their back, and they don’t want to know either.

Mrs FP and myself are almost 73 and our attitude now is: Do not believe anything on MSM.

Old Black country saying:”Doe believe onythin yome tode and only half that wot yoe con see”

Couldn’t agree more. We live in a rushed society where we take in small news bites (whether that be listening to the radio on the way to work, a quick scan of the news etc.) which make us know a little bit about something which makes us feel educated and in the know, but never enough to fully grasp it or understand it.

Whenever I’ve put forward material facts, the same as you, the replies I’ve always had follow these small bitesized parts of media narrative they’ve taken in

“Covid bad” – “vaccine good” – “vaccine safe”

No full grasp of the narrative, just regurgitating what they’ve heard and they think they’re fully understanding of the situation. Mind boggling

Occasionally my car Radio would retune itself to Radio 1. Sometimes I did not realise until the 2 minute news came on. For some reason they feel the need to run a rumbling/’exciting’ soundtrack to keep their listeners attention.

I have had that experience with pre-panicdemic friends, they just don’t seem capable of processing information which disagrees with their programmed mindset.

Comfort zone(s)?

I ask questions of the “conspiracy nuts”and they don’t like it either..seems like most folk like to pick a side and stick with it.

Watch the latest UK Column, and you’ll see an example of how, in the UK, the Branch-Covidian agitators view us – the British population – as little more than children, to be spoon-fed, and punished if we dare say no to them.

01:02:13 – Lockdowns For The Unvaccinated

https://www.ukcolumn.org/ukcolumn-news/uk-column-news-27th-october-2021

The bit I watched was a bizarre attack on Charlize Theron, firstly for her sad upbringing then her choice of film roles…if this is the best we can do then no wonder we lost the propaganda war.

Yes, that was odd and unnecessary.

I like the UKColumn. But all news channels have to be watched critically and selectively. The irrelevance of Theron (and ‘celebrity’ in general) as an advocate was a fair point, but there is a tendency, on the part of Brian Gerrish, particularly, to move beyond the evidence in order to paint a pre-conceived exaggerated conclusion that suits his particular predelictions.

“if this is the best we can do then no wonder we lost the propaganda war.”

We were outspent by factor one trillion (pick some huge number). Every powerful institution on the planet was/is against us and up their necks in it.

Another dry, soul-less husk shilling for the agenda, completely ignoring the data showing vast majority of covid deaths are double jabbed with more than twice the infection rate of the un-jabbed.

WE WOULD’NT KNOW THAT IF EVERYONE WAS JABBED. WE ARE THE CONTROL GROUP AND THE AGENDA CANNOT TOLERATE IT.

I took that UKHSA data to work the other day to show people and try to break the propaganda spell – they were dumbfounded and confused by it. Hopefully the cogs were greased enough for them to investigate further on their own, but it’s much easier to just switch off and believe the corporate media eh?

Which means that we won.

At an indoor bowling match yday someone asked if I’d had my booster, conversation went as follows..

“haven’t had the first two so can’t have a booster”

“everybody needs to get vaccinated to protect people like me, I’ve only got one lung and my husband there has leukaemia”

“but if you’re vaccinated what difference does it make if I am or not. Why should everyone including children be vaccinated with an experimental jab to protect you?”

“they’re not experimental they’ve been working on them five years”

“you’re right they have been working on them, unfortunately in all the animal tests they subsequently died which is why they’ve never had them licensed. To be honest, if I was that worried about my health I probably wouldn’t be in an enclosed space with lots if people and I most definitely wouldn’t think that everyone had a duty to protect me”

There ended the conversation, I’m not sure which bit shut them up.

“But I go on to say that sceptics have to accept some responsibility for their failure to persuade more people that lockdowns don’t work.”

One word: Sweden. My go-to example everytime.

I don’t beat myself up over that failure to persuade. I have tried a range of strategies, and have realized that little penetrates a brainwashed mind within a controlled environment.

‘sceptics have to accept some responsibility for their failure to acknowledge the so-called conspiracy theorists have been correct over and over again, and by dismissing them as quacks we are pissing on our own chips.’

No. The conflation with wider, more debatable issues is, I have found, one of the major barriers in convincing the unconvinced. It makes dismissal of the core issues much easier.

The unconvinced are trapped by their perception of what can and can’t be real. The evidence is all there for those willing to look at it.

I think he’s missed the mark here. If you go against the government and the general narrative you have to have facts, figures and a well constructed logical argument to still be blissfully ignored or labeled as incorrect.

Go with the government and their consensus and make a flippant statement or claim with 0 evidence or factual background and it’s accepted as ‘correct’.

The cold hard facts have been put forward many many times, but some people are just too far gone or unable to accept that the actual facts aren’t what they’ve been told to believe. It doesn’t matter what you put forward to these individuals, no matter how compelling, they aren’t willing to accept an alternative so it’s pointless

Because the media is part of a global conspiracy to overturn our way of life and turn us into semi-automated slaves.

This isn’t hard to figure out. Everything we feared is real.

If we kill all, covid will end. Don’t need lockdowns – do what Uttar Pradesh did.

.

With so many obese people in the country and a large healthy but ageing population who are at risk of illness even before Covid it didn’t take much to persuade them that Covid is a lot worse than it actually is.

The alternative media didn’t help the cause when many of them took the ridiculous line that viruses do not exist.

People like Lanka, Kaufman, Cowan et al persuaded people like David Icke, Jon Rappaport, Mike Adams etc. who all have a huge internet followings that viruses do not exist.

It was difficult to persuade any sceptics in the general public when the deluded alternative media were telling them that SARS-CoV-2 is not real and a hoax.

The Global Elites response to Covid was a hoax but the virus is real but no worse than a bad flu season which was something of which we could not convince the general public.

Toby Young et al should be congratulated for this website which stuck to the statistics and the science.

MMMmmm … The captured apologist for the repulsive Mr Toad emerges :

Johnson “just hasn’t been able to impose his will until now.”

Awww … diddums … poor ickle fing, bullied by all those other nasties.

“whisper it — I’m almost certain he’s a lockdown sceptic.”

Desperately trying to get back on the court bandwagon, TobY/

Pull the other f.ing leg. The snivelling, lying self-seeking twat has simply sussed that political progress lies in another direction.

“the success of the vaccine rollout”

You WHAT!!!!!?????

That rollout that created a wave of mortality of the vulnerable and did absolutely f. all in terms of infection and transmission, and provides the vehicle for anti-democracy?

Not that all is wrong. The sceptical case has been a miserable whimper, even if entirely correct after the emergence of further data at each stage. And yes, rationality is a weak weapon in the face of a studied brainwashing campaign backed by unprecedented censorship. (But no mention of the total capture of the media and censorship as the significant factor in terms of information- ?).

As to wrongness : for the record there have been only two ‘waves’ in a sea of predicted ones and little ripples, and many of us saw the second one coming, sucking up the general seasonal infection rise, even if we didn’t precisely forecast the jab-related additional surge.

Sorry. Must do better. Even if detaching from the teat is uncomfortable.

Trying to deny Johnson is personally responsible for a lot of the crimes against humanity commited in the UK since March 2020 smlels very much like how when Germans in the Reich disliked a policy they always said “surely Hitler can’t be responsible for this, it must be those other guys beside him”. Hitler was responsible, so is Johnson. However much their underlings did the dirty work, they knew it was going on, let it continue, and actively encouraged it, even if in Johnson’s case largely behind the scenes.

The belief that the great leader can do no wrong and is being misled by his henchmen is common throughout history from ancient times.

Down our way we didn’t have much of a first wave or second and that was it; the NHS was never remotely overwhelmed, the Johny-come-Lately Nightingale was never used and neither was the vast emergency morge.

There is plenty of anecdotal evidence suggesting a pre-wave (autumn/winter 2019/20) but if they stopped talking about Covid tomorrow it might never have happened, bar the collateral damage from lockdown.

Does anyone else ever wake up and think “jeez… maybe it’s me that is wrong after all?”

Are we also so blinded by our scepticism?

No, the evil is spreading and every day my resolve to resist gets stronger.

Never. And no. I question myself about this all the time, and I can’t persuade myself I’m wrong. I can’t find others to persuade me either, and I’ve looked.

Frequently. So I go and take a dose of BBC evidence free, illogical, hysterical so called ‘news’ and I compare and contrast with what is reported and referenced here and other non-mainstream sites. And that tells me all I need to know about what is truth vs what is lies and propaganda.

Nope, not since emerging from my own private lockdown that lasted the week before bozo announced his on the nation.

Spent most of it ‘in drink’ and never have seen that broadcast.

The predictability of what was coming next, and it was frequently predicted here and elswhere, kept my scepticism strong.

A quick look at one of the many horrific videos coming out of Victoria, Australia should solve that in a jiffy.

A good argument. Sadly, yes, those of us skeptical of lockdowns (or at least of their cost-benefit efficacy) we’re too optimistic post April. I for one thought seasonality was the biggest factor and then Delta rained on our Spring parade.

But I don’t think any of us was really well-versed on the psychological games being played with people. No, we weren’t thinking rationally (can hear Agent K in Men in Black about people being dumb, panicky and dangerous) in good times. But when you are subjected to a government approved campaign that the CCP probably envied, it was always going to be uphill. A willing media that published raw data workout context didn’t help either.

I do agree that we are unlikely to even see Plan B again. Beyond the fact that everyone with half a brain cell understands that masks with far larger pores than the virus can’t stop spread, the truth about vaccine passports has been revealed. But getting Hancock and Gove away from the switch matters more. Javid understands cost-benefit analysis, and that should save us.

I think that you may be over-estimating the logic of the general public, The increase in face nappies in shops over the past few weeks, as the government and media ramped up the rhetoric, shows that many still can’t think for themselves!

Yes, after falling quite rapidly up to the end of September I have noticed that mask wearing in supermarkets has suddenly shot us again after Javid’s recent press conference and BoJo admitting that the jabs don’t stop you being infected or passing the virus on.

There has been no general increase here, just gullible individuals wearing them again.

Just one in the co-op yesterday, fussy old git in his dads clothes creating a queue at the till while he decided what to put where, coupons for this and that emerging from different pockets, tv mags had to be facing up, couldn’t find his wallet; you know who I mean.

He was wearing a welders shield

“Many are destined to reason wrongly; others, not to reason at all; and others, to persecute those who do reason.” ~ Voltaire

“I do agree that we are unlikely to even see Plan B again.”

I don’t know how to speculate on likelhoods, I hope we won’t, but what we need to have is plans to resist it IF it happens, however likely or not we may think it. The presence of thsoe plans should also help act as a deterrent against Plan B.

I think it would be better for us if there were to be a Plan B implemented. Our only hope for a swift victory is for the Satanists to turn the heat up so much that the frogs realise they are being boiled. But in the main they are too smart for that. Instead we will have vaxx passports, threats of lockdowns, travel restrictions, persecution of the unvaxxed, evil mass vaccination of healthy children, billions wasted on mass testing, covid safety bollocks everywhere, and the survival of the Big Lie for decades. Lockdown is not over, it has just moved into a new phase. WE LOST (for now).

There will be nothing like the 99% compliance that happened with lockdown 1 but with winter upon us and if all ‘non-essential’ venues are closed again what reason would there be to go out?

I do know that lots of young people discovered that visiting friends in their homes could be just as enjoyable as going to the pub and perhaps restaurants also.

There is also the samizdat effect of people going off grid for their socialising/ entertainment.

Add up:

Increase in sales of garden offices / rooms.

Increase in garage conversions to home pubs.

Increase in sales of home brew wine beer etc, ( many of the online sellers are out o stock for half their lines)

Marquee sales or hires.

The tendency for those who came from or their parents came from east of the Iron curtain to distrust anything a govt tells them and do lots of activities without official stamps.

We are replicating many of the conditions which gave the mafia their big boost in prohibition, the only countervailing tendancy is people keeping it small / local to ward off the snitching Karens.

EU vax pass system private key may have leaked:

https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/news/security/eu-investigating-leak-of-private-key-used-to-forge-covid-passes/

Black Rock and Vanguard own the highly profitable pharmaceutical industry and all the main media (and possibly many scientists and politicians) – own the media own the narrative own the ‘truth’ – They use their media to promote their pharmaceutical product. These are very powerful dangerous organisations – a true cancer in the population. You didn’t lose the argument, your argument had the living shit kicked out of it by bullies with an evil agenda

The whole “cock-up” stance that some people hold so dearly gives those responsible (that we know of publicly) a way out when it comes time for crimes against humanity charges and other necessary actions,in my opinion.

This war isn’t lost, lockdown sceptics never lost the argument. They were not even allowed to engage in the conversation. And when they do have a say it is like talking to a roast turnip with most people. The Globalists are terrified of genuine debate and honesty, hence the ceaseless propaganda. However this has only just begun. Humanity will prevail.

And isn’t it funny how the Crypto Globalists (Communists, Fascists, Eugenicists, Green Tyrants) have come to the fore in the past 2 years and they are quite brazen about their intentions now e.g. Joanna Lamond Lumley. But at least they have exposed themselves…

Instead of arguing whether lockdowns work or not the better strategy might have been to argue that even if they worked this disease didn’t justify using them any more than the Hong Kong Flu of 1968 which had a comparable death toll in the UK (80k when the UK population was much lower). However due to the increase in Snowflakery in the UK population since 1968 that argument may still not have dented support for lockdown much.

Not sure that’s true as it implies that they might work and leads to discussions / arguments about the level of risk at which they are justified. Those against them are immediately on the back foot as they have already accepted something which is demonstrably false.

“the better strategy might have been to argue that even if they worked this disease didn’t justify using them” That was argued often. Some of us oppose lockdowns on principle under any circumstances, others would accept them if the cost/benefit analysis was favourable (bearing in mind the cost side must include a notional cost for loss of freedom). We lost because, as it turns out, the world is mainly run by Satanists and human beings are easily brainwashed. With hindsight, the surprising thing is not coronamadness, but that it has not been tried before a lot more often.

Most people liked lockdown 1 because it was a cushy number, kids off school, parents on furlough or working from home. Government subsidising this that and everything else. Even the weather was nice first time around.

Most have forgotten what ‘civil society’ means but the government knows it cannot afford it again which is why my fags went up 10% today, bastards.

A number of people did try to address this – the issue is basically that a large proportion of infections (and especially of those at risk of serious illness) took place in healthcare settings of one type or another – hospitals and care homes particularly, and in private homes. Lockdowns didn’t have much effect on spread in healthcare, and may actually have made it more likely in private homes as people were cooped up together more. There is no evidence that shops were in any way significant in spread (not aware of any outbreaks traced to a particular shop), so shutting them is likely to have made no difference. Likewise with many leisure venues – plus people fit enough to be using a gym or other sports venue are in many cases the type of people who would have few or no symptoms anyway.

Plus of course many people still had to go out to work – only the laptop classes had the luxury of being able to ‘work from home’, so the ‘lockdown’ could only ever be partial.

Even if those theoretical reasons why it wouldn’t work didn’t convince the doubters, it was certainly the case that there was sufficient hard data from around the world by the middle of last year to show that in practice lockdowns are not correlated with lower cases, and therefore the evidence shows that they don’t work. That didn’t prevent governments from imposing yet more of the same!

But the biggest problem is that the MSM and government, and social media, actively censored anyone opposing lockdowns – this is undoubtedly the biggest reason why the accepted ‘wisdom’ came to be that lockdowns work (and the same applies to muzzles of course, where many think that they reduce infections despite the hard evidence clearly showing that they don’t).

I’m not sure that the argument that there wouldn’t be a Wave 2 was incorrect. There was far more testing going on in the autumn and winter than in spring 2020 so of course it looked like there were lots of cases.

If you look at the excess mortality graph for the last two years (and I know it’s not a perfect dataset to use but all causes deaths are a better measurement than anything involving measuring COVID) it is clear that the rise over autumn and winter was not due to another epidemic wave – the shape of the curve is entirely different from the one last April.

And if the vaccine rollout hadn’t killed off many already frail people (and we all suspect overuse of Midazolam) and we hadn’t locked down people again there’s every reason to believe there would have been much less death recorded in the autumn, as we saw in for example Sweden.

I have to confess that I tune out when there are long arguments based on statistics. This is a problem because statistics are necessary. But there is always the suspicion that there is some error, something omitted. If the authors have not spotted it (or are hoping the reader will not spot it) how likely is it that someone without a Ph.D. in mathematics or epidemiology will? The old adage, “Lies, d***d lies and statistics” holds. Perhaps there are writers better at explaining statistics than others. In the end it depends on whom you trust.

“The old adage, “Lies, d***d lies and statistics” holds.”

No it doesn’t. It’s oft-quoted bollocks. The only defense you have against lies and distortion is actually proper statistical analysis. The alternative is magical thinking – i.e “In the end it depends on whom you trust.”

I have some statistical training so can follow a lot of the statistical arguments, and strongly did in spring/summer 2020, but since then we’ve seen statisticl arguments just don’t land with the lockdownists and the brainwashed. They weren’t put in those positions by reason and reason won’t get them out. Since then I’ve followed the stats less closely as I know that they aren’t changing anything.

I don’t disagree with your last sentence, as I’ve previously pointed out. But neither is anything else working.

However, that doesn’t contradict the fact that is is data and its analysis that establishes the rationalist case.

The only stat that interested me came from ONS, 3rd week June 2020 showing fewer people died in London that week than the five year average, that stayed constant and spread throughout the country.

As clever people here pointed out

You can’t die of Covid in March and then die again in June of the underlying condition that was going to kill you anyway.

At that point it was obvious that Covid had done its worst and it hadn’t been all that bad anyway.

It was a mistake to claim there wouldn’t be a second wave. Sunetra Gupta warned that the prolonged lockdown, in 2020, would lead to a much worse resurgence of the virus, in the winter, than would have occurred if we had opened up and allowed people to encounter the virus in the summer months. The lockdown made the situation in the winter worse. Back when he still told the truth Vallance warned of just such a scenario.

I think the argument at the time (although possibly not very well articulated) was that if we had opened up completely last June then people would have got out and about in the summer, upped their vitamin D levels, allowed the virus to spread among the less vulnerable during the summer when the NHS is under less pressure, and make any residual “wave” in the autumn and winter smaller.

But instead the government brought out the mask mandate and increased testing to keep the fear levels up and keep the worried well inside, probably making the autumn and winter situation worse. Added to which the vaccine rollout bumped off a lot of already frail people early, and there is all the speculation about the overuse of Midazolam bumping up the January and February death numbers.

I think that the lockdown sceptics ‘lost’ the argument because:

a) the system (MSM, government, academia and the civil service) is stacked against them, either by sheer numbers or blatant censorship, and;

b) most scpetics often go by their ‘gut instinct’ based on experience, but often do not follow up that with a significant amount of thorough research to completely back up their assertions.

Bear in mind they are often going up against zealots who’s whole career is now dedicated to getting more control, censorship etc and they are willing to do anything to justify it – including lying. smearing, and using others to do their dirty work, which often ‘launders’ their own claims to make them respectable.

Most of us are too busy with real jobs/lives to spend all day doing this or don’t have loads of willing (naive) believers/minions to do the scut work on our behalf.

a) Farage was up against all of that yet still won.

I think it’s more to do with the incestuous way the politicians, media and academia wrap around themselves making it easy to stifle informed opposition especially as they all ultimately depend on state handouts for their ongoing careers.

All I have to offer to the debate is what I see with my own eyes and something of an understanding of history. This leads to my gut instinct that I was right to be a sceptic initially and I am still right now.

Ironically, Brexit was a far easier battle to win than those we face at the moment, as:

I would also suggest readers here watch the videos of the YouTuber ‘Black Pigeon Speaks’ (he has two YT channels [both mirrored on BitChute and Odysee], including a second channel called Felix Rex [added when YT temporarily banned him a couple of years ago I think]), especially his most recent video entitled ‘Public Lies, Private Truths: How a Dystopian Future Begins’ at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1rqGAIZrpUY

This goes a long way to explaining why Brexit and Trump succeded in 2016, the Tories did in Dec 2019 but Trump and the ‘lockdown scpetics’ and anti-woke grpups have failed.

This article concedes far too many points unnecessarily.

It is a waste of time arguing on the opponent’s choice of territory. Everyone now believes they are an expert in virology and all you get back are half-digested semi-medical clichés.

When this subject comes up, I begin by refusing to discuss viruses, covid fears, vaccinations…instead I state clearly that I have fears for my savings (to instil a different fear into their heads.)

I point out that our government are engaging in corruption and asset stripping of the country on a massive scale, remark that the banks repro rate soared in September 2019 before CV started, ask them whether I should invest in gold, given that the fiat currencies are collapsing, (say that I have friends who are already doing this) ask them what will happen when the interest rate goes up (mortgages and business loans) point out that the banks can recapitalise themselves on the bankruptcies and repossessions they will create by doing this, point out that this has been planned since 2008 as it has been inevitable since then, say that CV is just theatre, say that “it is always about money at the bottom of anything.”

Give them some different suspicions and new fears, rather than the ones they are being programmed to have.

You can see new ideas dawning, as they start to put two and two together.

Their fear and hate need to be redirected onto the correct object.

My friends don’t talk about banks repro rates or buying gold but they do notice prices going up in Tesco, not being used to inflation.

One old boy is going to be very upset when he finds that Rishi has raised the price of his tobacco by 10% today.

I’ll tell him it’s to pay for the vaccines.

I should invest in gold, given that the fiat currencies are collapsing,

Gold is a fiat currency. Except insofar it’s being used because of its chemical properties in certain products, the only reason why it’s considered valuable is because people believe it to be valuable. To an ordinary person, it’s of no use whatsoever.

Be optimistic that there will be no Plan B and no lockdowns, sure. But we also need to propare to effectively resist, defy and sabotage any Plan Bs, vax passes or lockdowns which might arrive. Hope for the best, prepare to fight off the worst.

“if we’re going to persuade people that lockdowns don’t work we need a compelling theory as to why that hypothesis is false”

That is very easy to address. Right from the start all cause mortality was higher than previously.

Only true until 3rd week June 2020 when it was all over and even then nothing like as bad as they thought but by then they had wrecked the economy and so could not just stop.

Main reason sceptics lost the argument was that they didn’t really put forward an argument that could stand any scrutiny. It was always about objecting.

Facemasks don’t keep out Covid anymore than underwear keeps in farts. Refute that.

“ they didn’t really put forward an argument that could stand any scrutiny.”

Well – that’s a load of bollocks. It was the Covmaniacs who did that. But rationality made no impact.

OMG, you probably think you take a vaccine to protect someone else. Like if the mother takes the contraceptive pill the daughter doesn’t get pregnant. That’s the sort of convoluted logic and double-speak that people now take as fact.

Well, the progress we’ve made as a species has in large measure depended on rationality and science. Assertions not backed by evidence are assumed to be false until there’s some credible evidence presented that they are true. If you chuck out pandemic planning that was internationally agreed upon for decades and replace it with measures for which there was no evidence as to their efficacy, measures explicitly advised against by the WHO prior to 2020, and these measures are incredibly damaging, then the burden of proof is on you. So yes, we object to evidence-free measures that are damaging because we are not stupid.

I don’t think you did fail Toby unless you set out to change government policy as Farage did with Brexit.

Before Covid arrived but was looming abroad I was sharing doubts on a couple of small blogs with people who seemed to know what they were talking about (correctly as it happens).

Someone pointed me to Lockdownsceptics which was reassuring as I could see that a great many different people from all walks of life, political persuasions and points of view shared my doubts.

This made it all the easier to ignore, whenever possible,* the ever changing ever more crazy lockdown rules and regulations.

*obviously I couldn’t use a pub if it was closed due to lockdown.

One thing I never did get used to though was that most of the very many people I spoke to during lockdown proper were perfectly amenable to sceptic discussion, often expressing agreement then slipped on their mask and headed for the sanitiser station eager to comply.

I agree to an extent; I think ‘we’ lost the argument because we were forced to argue on their technocratic terms. The emperor has no clothes, this is a common or garden respiratory disease that requires no societal intervention whatsoever. Let alone everyone’s lives to be ruined and the economy wrecked. As soon as we were looking at graphs and citing ‘cases’ we’d lost the argument.

“… this is a common or garden respiratory disease that requires no societal intervention whatsoever.”

You are contradicting yourself, since this is a technical argument, requiring evidence – unless you just assert the fact, which wouldn’t have got you anywhere, either.

The whole point is that the blanket propaganda shaped belief.

The “second wave” or Delta variant replaced flu in December 2020 on a large number of death certificates. When excess death figures for 2021 are issued (May-June 2022) the figure will be about normal for a 5 year average even if you were to factor 2020’s 71,000 out of the equation.

Let’s not concede that the second wave was a Covid extension, rather than a replacement virus.

I’m not sure that the Delta variant was actually flu but it seems undeniable that it arose because the original Wuhan virus mutated to defeat the antibodies being created by the vaccination programme. All of the various variants arose in countries which were involved in the original AZ clinical trials (England, India, South Africa, Brazil). And we know now that the Delta variant in particular evades the immunity created by the vaccines almost entirely (because the antibodies created are specific to the spike protein and not to any of the other proteins in the virus).

So without the vaccination programme there is in argument that there would have been no Delta variant and therefore no “second wave” and the scientists who predicted little or no second wave would have been correct.

“But I go on to say that sceptics have to accept some responsibility for their failure to persuade more people that lockdowns don’t work.”

No, I accept no such responsibility. Has every argument put forward by every sceptic been perfect? No. But we lost because we were outgunned by Satanists (or loonies, take your pick) who control the world.

Took the dogs to the vets this am. Conversation with the vet moved to CV19 after a sadly predictably ‘request’ for me to wear a mask, which was handled rather firmly by me. Never worn one, never will.

I asked him what he thought the IFR of CV19 was. His answer was “5%”. That’s what we’re up against folks. I of course set him straight on this and other untruths referring him to scary facts plus things like Florida’s experience and the brilliant work of John Ioannidis.

In one glimmer of hope, he did say that he thought big pharma had played a role. Just maybe, I gave him a little pause for thought.

We’re at war against the truth folks and will be for a very long time. I know all on here know this. I firmly believe that over time the destruction of lockdowns etc will become a self evident truth for the majority. Its just going to take a long long time to get there. We’ve just got to keep putting our shoulders to the wheel.

Keep fighting!

Well done. It’s good you asked the question about IFR rather than just tell him the answer. Getting people to start thinking for themselves is key to waking up the hypnotised ones.

Thank you. It gets better. I didn’t expect to write an update but the manager at said vets just called me to effectively tell me off for upsetting one of her staff when she asked me if I was ‘medically exempt’. Suffice to say, we’re changing vets.

I asked this person to estimate the IFR. Their response was ‘15%’!!!! They’re members of a jeffing cult that’s been propagandised into thinking that a plague is still stalking the land!

Onwards and upwards, the fight goes on.

Businesses losing customers and being told the reason why is another way of waking people up. Anything which disrupts “normality” for them. Well done again!

Nice one and very well played! I might follow suit and start asking people that question, just as a sort of litmus test to see how clued up they are in doing their own research and not relying solely on msm, as I have a feeling the IFR doesn’t get a regular mention on the BBC. Not watched that shite in many months as the bilge churned out was nauseating. And that’s before I even mention that annoying idiot Naga Munchetty!

first reason you failed: if people do not mingle the virus cannot spread.

second reason, your site was swamped by anti-vaxxers, hence your site became a basket of deplorables.

Use slogans and clichés like anti-vaxxers when you don’t have an argument. I think it’s common sense to weigh up the options: possible death by injection against catching a virus that 99.5% (underestimate) recover from. At the moment looking at the statistics you are more likely to die or have serious adverse reactions from the jab than the rona so it’s a no brainer. (Apposite phrase since it seems most people who advocate the jab have misplaced their brain.) It’s not a vaccine but I wouldn’t take it for the same reason I wouldn’t take a flu jab. They’ve been going 20 + years and I’ve never had the flu.

You left your tin foil hat behind the sofa

I remember being labelled by people like you (in fact you may well have been one of them) as a “racist” and “little Englander” and “xenophobe” and “bigot” with no attempt to engage in any argument about the actual issues of EU membership. This was all an attempt to avoid a debate which these people feared they may lose, and to demonise those holding a different opinion.

Well in the end it didn’t work with Brexit and it won’t work with lockdown scepticism. All it does is harden people’s attitudes and make them more determined to win.

Hey ewloe (if you’re an actual person – I’m kind of on the fence on that one?)

what’s an anti-vaxxer? I’m dying to know because I keep reading people refer to them. What is one can you tell me? I’m not having the covid vaccine, I think anyone who’s taken it has made a terrible mistake, I won’t let my children anywhere near it and my wife and all our friends aren’t having it ever, either. Are we all anti-vaxxers? Am I a deplorable? To make it more complicated for you, prior to the spring of 2020 I had no particular opinions about vaccines whatsoever.

I see – so perhaps you can explain why worldwide there is no correlation between the level of restrictions and the actual case rates?

Lockdowns do work because they were never about suppressing a virus, but about demoralising, dehumanising and dispossessing the population. And the work goes on through the jab. Weigh up the risk of possible death by lethal injection versus all but exclusion from society. These people are tyrants and we are at war. Why are people still pussyfooting about on this and pretending it’s got anything to do with health? Since all cause mortality is up by about 13% (source was here yesterday. Heneghan I believe) it’s got fuck all to do with health. And yet Toby – for all his virtues in starting this site and the FSU – still thinks that’s what’s driving it.

I take my hat off to Toby his energy in this cause has been remarkable but for once his intuition for what his side of the political spectrum wanted from him has let him down. He has created a great deal of animosity and this is Toby saying sorry to his old mates. Notice that the article is published in the house magazine of his previous supporters, its like making up to your Mrs after an argument ‘Look we were both wrong, if only I had explained it better we wouldn’t have fallen out in the first place’. Toby has been convinced by his contacts that it is all over and its time to kiss and make up if he wants those lucrative commissions and the contacts which lead to a seat on those red benches. I hope he is right about it all being over, at least for now!

No, Toby, you lost the argument because in line with your free speech agenda you keep publishing plenty of ridiculous gibberish through your site, not having the money/resources/inclination to hire staff who would actually check that. And that is why nobody in charge really takes you seriously.

Far from “appealing to reason”, when you browse through the comments, most of them are rooted in pseudoreligious beliefs and emotions, and the selection of articles published here clearly panders to that audience.

Could the Daily Sceptic be more effective with a bigger budget? Yes.

Could the Daily Sceptic, with better funding, defeat every powerful institution in the world? No.

The main problem is that attempting to debunk fallacies present in mainstream media draws in crazy people who are committed to even bigger fallacies of their own. This process automatically discredits the moderate well-reasoned critic (which Toby himself claims to be). As the saying goes, “with friends like that, who needs enemies”?

And of course the mainstream is very eager to single out the most extreme and craziest people to whack all the critics by mere association. The same technique is also used to terminate new non-mainstream political parties.

Sad as it seems, tightly controlled and censored media have a huge advantage because they can appear more reasonable and authoritative to an external observer – which is what helps them win even the wrong arguments.

We didn’t lose because of a few “cranks” or whatever. We lost because the enemy had a bigger army than we did.

Yes, we lost the war but our arguments were for the most part correct.

It’s a bit like the old saying in the investment world – “the market can remain irrational for much longer than you can remain solvent”.

More a case of the enemy having a massive propaganda machine!

And yet, you’re always here.

1984

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4X1A5gxJn_I

Imagine had we not tried and Toby not taken the risk to set up this website. Thank you for trying and for bringing people together on here to support each other

Bringing us all together here is what worries me!

Such information is useful to the security services who no doubt come here just as we do, to read this.

True, but “they” can’t resist commenting here….so sure are they that they are right and we are a minority….I am not so sure that is true

Lost the argument? You had the entire government and the entire media against you.

In essence, you were ignored.

“The greatest power of the mass media is the power to ignore. The worst thing about this power is that you may not even know you’re using it.” Stan Smith

Yes, if they pretend it didn’t happen, it didn’t happen, as far as they’re concerned.

https://amgreatness.com/2021/10/27/drinking-problems/

“Well, the results of this lockdown folly are in: the biggest wealth transfer from the poor to the rich in history; millions of poor schoolkids now miles behind their better-off peers; millions thickening hospital waiting lists, many of them tragically too late; a mental health crisis; public finances in tatters, and the unedifying realization that one-third of one’s fellow citizens would relish the social-credit-system drudgery of Beijing.

Remarkable is the thought that anyone—let alone the entire Western political class—took as a measure of sophistication the Chinese method of amputating at the shoulder what tingles at the thumb.”

Common sense dictates that if you confine most people to their homes then infections will start to fall

It’s not common sense which dicated that but Chinese state propaganda. The people in favour of lockdowns were always carefully cherry-picking their example of the day, jetting around the globe at a breathless pace in order to make the most of whatever chance gave them. In contrast to this, the lockdown sceptics (I’m not a lockdown sceptic, I’m a lockdown opponent) always saddled themselves with finding alternate explanations for the same examples. That was a game they were obviously bound to lose. A better tactic would have been to accept that different things happen in different places by chance, ie for reasons unknown to us (we cannot really determine) and also pick whatever chance presented. Eg, Germany was in permanent, harsh lockdown (much harsher than it was ever in the UK) from fall 2020 until after spring 2021 and dutifully had a Corona-wave nevertheless the moment lifting of restrictions started to be discussed. This obvious example of lockdown not working was then used to argue that it must be continued.

But then, conspiracy theorists believe that making up explanations leads to insight instead of to pretty gothic novels, so, this was sort-of their achilles heel from the start.

just one small problem with that – at no point were most people confined to their homes and I’m not sure that’s even possible without the total collapse of society and complete anarchy.

There’s also the question of how it’s actually transmitted. How do all those people on boats get it after testing negative prior to boarding? (or the people at the south pole who got flu weeks after arrival).

Indeed. Only China came close to doing that, but not nationally. It was regional, and the sent people in to do essential stuff. We never had a lockdown here, as such, just theatre.

Exactly. As Luke Johnson said, lockdown in reality involved “middle class people staying at home and working class people bringing them things”. There was plenty of scope for the virus to spread.

just one small problem with that – at no point were most people confined to their homes

Even when granting that, for most people in cities (much more so in China(!)) being confined to their homes meant a fair lot of people spending unusually long times in pretty close proximity in flats in shared houses with fancy gadgets like shared ventilation systems ensuring that whatever is in the air somewhere inside the house will eventually end up everywhere. In order to achieve isolation, individual people would need to be confined to hermetically sealed cells with suitable filtering to prevent contamination getting inside via air intake. People used to do preparations for ABC emergency situations in the course of a future war in the past and the idea that everyone staying at home would help against contagious biological warfare agents didn’t feature prominently in them. They were using something seriously more elaborate.

Similar to that, PPE and open plan isolation procedures to protect against COVID in hospitals. That’s certainly not what they did for Ebola when that was current and even what they were doing back then didn’t reliably protect people from getting infected.

Unfortunately, common sense frequently equals the BBC said so even when what the BBC said plainly contradicts observable reality.

I felt sure that the battle had been lost by end March 20 because too few at that time spoke out against the way the situation was being handled.

By then, the momentum was un-stoppable. It may have been so by early March 20.

But too few had the background knowledge and it took a while for many to learn, understandably so

Too many people benefited from lockdown as a result of the ease with which people could work from home and still be fully paid (but with much less expectations for productivity) or be furloughed and have very little do to at all.

Classic overthinking.

We “lost” the argument because while we were trying to have an argument, we were surrounded by the governments of the world simultaneously blaring through their enormous megaphones that everyone needed to lockdown.

There was never an argument. Nobody listened to us because they couldn’t hear us.

Because they didn’t want to listen! The Agenda had already been set.

Maybe, deep down, many in this country still see themselves as serfs and will blindly follow the rules, as dictated to them by those perceived as ‘authority’. “It’s much easier that way, you don’t have to think do you, or be held responsible…”

You do have a point. Too many people think those in government are the creme de la creme and therefore completely trustworthy when in fact the opposite is true. Deluded or what??

I think this article is very defeatist. We haven’t lost the argument at all. I have been studiously following the internet ever since day one of the Plandemic. I believe its gaining traction.

Nil desperandum carburundum illegitami

Maybe not ‘lost’ (past tense) but we are far from ‘winning’. Note the recently mistakenly published then removed research paper from the HMG website (still available courtesy of the Internet Archive), which noted (bold added):

That’s your problem right there. Many of our fellow ‘citizens’ positively revere government. (I’ve observed repeatedly: State schools are faith institutions inculcating the worship of government more assiduously than any RC school ever cultivated faith in Christ.)

It is written to inspire defeat? Controlled opposition?

Reminds me of Peter Hichens public trumpeting of his own capitulation.

As “lockdown” is not and has never been a response to a comparitively trivial disease and as governments have their instructions we could never have “won the argument” against it.

Could we have persuaded more people in the group who aren’t mentally ill but are just going along with the evil for a quiet life? Possibly, but it wouldn’t have made any difference, because see my first para.

For the last time, dialectic doesn’t work in politics. You need rhetoric.

“We have lost millions of jobs, thousands of cancer screening appointments missed, just so that Boris can show his girlfriend how hard he is! Gove might be impressed, but for what – a virus that most people stand a 99.9% chance of making a full recovery from. He’s a coward and a liar and an embarrassment to fat blonde people everywhere”

Imagine Farage stomping back and forth on a platform saying this. That would have been a million times more effective than Toby’s tweets.

Instead, he did a video outside some refugee camp where he said ‘these people come here illegally – you never know, they may have Covid’. Good use of rhetoric, just wish he hadn’t used fear of Covid in his spiel against immigration.

Like Trump, Farage has been quite cautious around the topic of Covid, possibly due to them themselves not being at trivial risk from it, given their ages, but also out fear of alienating their target audience.

“given their ages”

Farage is only 57.

Absolutely! At the beginning I thought TY might be up for it: instead he just gave in and now regularly sucks up to Bozo.

To add to this, ‘sceptics’ instinctively prefer dialectic and are bad at rhetoric. Prime examples: Steve Baker and Mark Harper.

Libertarianism has done better in the US than elsewhere precisely because of the founding myth of the United States; cries of ‘freedom’ have emotional significance there that they don’t elsewhere in the world, except maybe France.

Fear is incredibly powerful and even a skilled rhetorician like Farage could do no better than help put fire in the belly of, say, the 20% most sceptical part of the population. That is probably enough to prevent the most excessive response from the government.

The ‘anti vax’ message is quite powerful. That of course, is why the PTB label it as anti-science. Fight fear with fear, as it were. Doubling down in this department might be productive. No need to be ‘proportionate’ – it’s not like the other side bother with caveats.

Blimey, there are a lot of arguments here about something very simple.

40% of people depend on the State, they do as they are told ( most of the time)

40% of people got paid off to stay at home, most of them enjoyed that at least for 12 months or so.

20% of people, for many varied reasons, are reasonable immune to psyop in its many forms.

The State couldn’t afford to keep all of the 40% paid for being at home, working or not, so devised the escape route via injections and passes. This 40% having swallowed the pill , go along with the scam, and it helps them to see the 20% disadvantaged, everyone is open to a bit of schadenfreude.

As this cunning plan by the State enriches politicians, public health dignatories etc by crumbs from the Pfizer business model profits, so much the better. Even more so if it panders to inate totalitarian tendencies which are required for the bounty from ‘zero carbon’ investments.

Within this structure can exist various types of governing bodies, all ultimately driven by power and greed. And all bankrolled by the $trillions under management by the likes of BlackRock and directed by the BIS and its CBs.

And you think a few of the 20% ‘failed’? The fact that we still can communicate and indulge in minor indescretions is a minor miracle.

“so devised the escape route”

Escape route from what?

From supporting 40% of the population financially which was never sustainable.

They dug the hole they had to find a ladder that was consistent with the psyop. So called vaccines and passports gave them the solution, even if they knew full well that the jabs may be useless. The passports gave the jab victims the ‘prize’ of ‘freedom and travel’ as well as the means of continued control for the great zero carbon scam.

So you support the “panic cock-up ” theory?

I wouldn’t agree with all of your assessment but the general thrust – that we are outgunned – seems obvious. I get that people don’t like to think things are as awful as they seem, but I am a bit puzzled by TY’s seemingly unfailing optimism in the face of the sad truth. He’s got far enough to see that all of this was wrong, but desperately wants to believe it can be fixed. He ought to know from his struggles to fight for free speech that we’re massively outnumbered.

It’s quite simple, Tobes: you gave them an inch; they saw it as weakness and took a couple of miles.

No one is saying lockdowns don’t reduce infections (I’m not anyway). They don’t reduce deaths though which I suspect is because fatal covid infections are usually acquired in a care home or a hospital, so lockdown makes no difference. We have data on the former but I’ve not seen any on the latter. Needs to be audited. Hugh Osmond has been big on this. Tbf saying a respiratory infection wouldn’t be back in the winter was always a bit contrarian Toby!!!

– except (ssshhh…) he still thinks the call from the PM is coming.