Last week, the Health Advisory and Recovery Team (HART) published an article advocating the use of “ethical frameworks” to counteract disingenuous government behavioural science techniques. HART argues that deliberate use of fear tactics, shaming the non-compliant and covert ‘nudging’ are unethical and must be challenged by explicit ethical standards. As an example, they cite the “Seedhouse Grid… developed to promote ethical decision-making in health care”.

It is naturally pleasing to read that a tool I invented 35 years ago is still considered relevant, though the Ethical Grid (to give it its correct title) represents much more than a set of guidelines. The idea is simple. First, since labelling a decision ethical or unethical will always be controversial, the emphasis should be on the deliberative process rather than rules: the question is not “has ethical rule X been correctly applied” but “have we balanced sufficient factors as we work out what to do”? Second, rather than enshrine a set of objective principles, codes or pseudo-laws, the personal nature of ethical judgement should be embraced. Third, ethics is therefore best seen as a transparent form of critical thinking, always open to revision in the light of new evidence and argument.

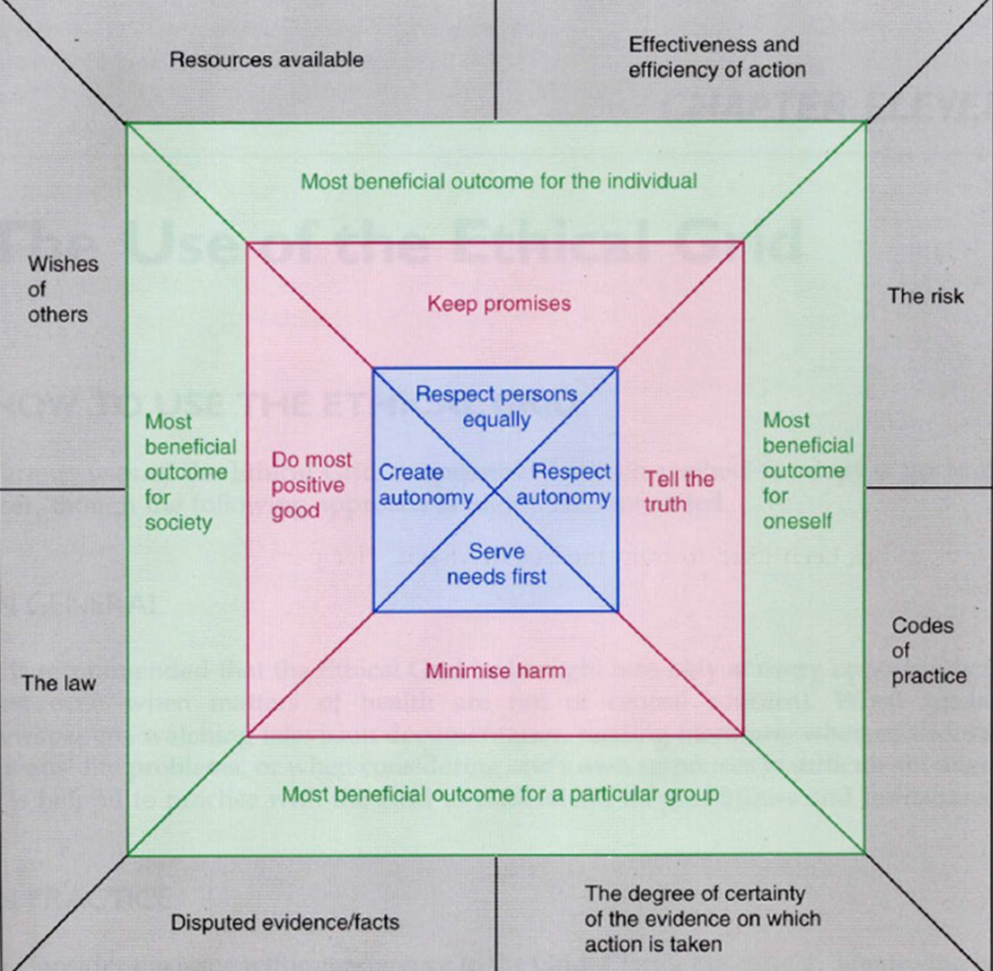

The Ethical Grid looks like this:

Its layers represent four necessary aspects of competent social decision-making, whether done by individuals, groups or larger organisations, including government. They encompass practicalities (black), consequences or outcomes (green), duties or obligations (red) and purpose or rationale (blue). The choice of segments in each layer is not fixed, the concepts are possible rather than necessary – for example, ‘uphold rights’ might be preferred to ‘do most positive good’ and ‘most beneficial outcome for the most disadvantaged’ might replace the more general ‘particular group’.

In this example the blue boxes have a special role, summarising key components of working for health. But these too might be changed, for instance a Grid to support ethical journalism might offer ‘objectivity’, ‘balance’, ‘accuracy’ and ‘accountability’ in the blue layer.

There are several ways to apply the Grid to real-world decision making. Privately it can work as a prompt, ensuring that significant elements are not overlooked. Used in groups it is an evocative catalyst for creative conversation. Were it to have been used in the recent Archie Battersbee case, for example, the deliberative group might have involved the family, the Trust, experienced health care practitioners, legal experts and psychologists. The Grid could have been projected on a screen in a discussion room or implemented digitally. A proposal could have been put forward, say: “Life support will be discontinued after two weeks if there has been no improvement in Archie’s condition”, and participants invited to agree or disagree, referencing key segments.

Using the Grid is far from a check box exercise, nor is it intended to be applied by rote, rather it is meant as a flexible, exploratory approach to tough decision-making in which meanings and preferences are brought into the open. Possible meanings of each segment can be defined by the participants in the context of the issue at hand (and may be defined differently dependent on participants’ priorities); each participant can identify the most important segments in his or her opinion; and practical information (law, level of risk, availability of resources and so on) can also be clarified.

In order to judge who should enjoy the “most beneficial outcome”, ‘benefit’ must be defined and potential outcomes evaluated. Does “maximising benefit” mean ‘indefinite life’ for Archie and others in similarly tragic situations, or does it mean ‘a peaceful death’? If Archie is to be ‘respected equally’ with others, does this mean he should be supported to the same extent as patients with a better quality of life, or does it mean being treated similarly to others in this sort of situation? How certain is the evidence? What are the risks? Can we somehow accommodate ‘risk to individual existence’, ‘risk of devastating the family’, ‘risk of setting legal precedent’, ‘risk of unwisely using scarce resources’, ‘risk to religious beliefs in the sanctity of life’ and ‘risk to the Trust’s reputation’ in such a way that everyone involved can have their values acknowledged?

Any Grid analysis might head in many different directions, but using it will help ensure a comprehensive ethical investigation. Purposefully applied, the Grid inevitably brings values and disputes into sharper focus.

The result of using the Grid is al ways unpredictable. And it is this very uncertainty that is so vital and humbling. There are rarely if ever any right answers in ethical complexity. Open minds are essential, as any serious attempt to apply the Grid shows.

What if decision-makers had used the Grid or similar overt decision-making strategy in the U.K. in March 2020? It would have required insight, courage and humility in that febrile atmosphere, but it would have given ministers breathing space to contemplate alternatives to the ethically blind hysteria to which they so easily succumbed.

The Grid could have been used to make the case for lockdown, perhaps focusing on ‘risk’, ‘benefit for society’, ‘minimising harm’ and ‘serving needs first’. But this would have required a comprehensive rationale and a systematic ethical defence of any changes to civil liberties and established law – using the Grid demands a full and honest exploration of all its factors, in combination and in context. Sticking stubbornly to a bizarrely purist version of ‘following the science’ would not have been an option, nor would journalists who used it have found it quite so easy to denigrate protesters. We were after all simply asking for a little common-sense.

It is quite extraordinary that governments around the world were able to ignore the blindingly obvious fact that decisions of such massive import – locking down society, imposing sweeping laws preventing normal behaviours and coercing people to accept experimental interventions – are so abnormal that they require all-embracing ethical justification and should not be permitted in its absence.

HART is right to call for explicit ethical frameworks, but such declarations are a first step only. As we witnessed, even the most carefully crafted ethical pronouncements are shockingly vulnerable to the whim of ignorant news media and politicians, many of whom seem to have no knowledge of the history of medical ethics or the battle to establish universal human rights in the aftermath of brutal 20th century wars.

The act of deliberation and the freedom to reflect openly matters much more than any specific set of principles. Given the disastrous consequences of the absurd official response to Covid, we must somehow try to ensure that any future policymaking of such consequence must be subject to sustained and participatory ethical processing.

Dr. David Seedhouse is Honorary Professor of Deliberative Practice at Aston University and the creator of Our Decision Too, a free website of participatory democracy which welcomes new members.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Ethics, politicians. Please they are self centred, emotional and looking to fill their pockets with loot. They are the worst selection of humanity we could possibly have. Think of them as criminals, then it’s understandable why they show no interest in improving their so called constituents lives.

Please they are self centred, emotional and looking to fill their pockets with loot. They are the worst selection of humanity we could possibly have. Think of them as criminals, then it’s understandable why they show no interest in improving their so called constituents lives.

Any contrition shown by Government Ministers – including Truss and Sunak – should be weighed against the continuing use of the Behavioural Science Team (aka nudge unit) to weaponise climate change as part of their command and control net zero ideology. The deeply unethical use of these tactics against the British public continues unabated.

It’s a potentially useful concept, but it’s just as well that it’s flexible. After all, fashions come and go, even within an established agency within the Civil Service. It’s worth noting that many politicians are like the visible part of an iceberg, in effect. Experienced Permanent Secretaries and the ‘army’ under the sea can be difficult to manipulate, perhaps in an (internally) unpopular direction.

Basically it states that individual human rights trump collective rights.

Now if only folk had been allowed to make decisions based on personal circumstances rather than the hysterical “Do Something! Anything” decision making foisted upon us by the MSM & quite happily followed by the supine politicos who were ‘just following orders’….

This might answer the question *how* to think ethically. It does not answer *why* to think ethically. Too many people evidently don’t know.

It’s great to see this article in DS.

I was impressed with it when I first came across it as a student nurse in the 90’s, being particularly interested in ethics and it’s application to decision making in the health care setting.

It’s deontological, principal based core is central: the practical consequentialist considerations that are necessary to implement this in the real world are secondary. Many of the problems in healthcare occur because decisions are founded on looking at groups by policy makers rather than individuals.

The real problem in the context of the COVID decision making is I’m not too sure that career politicians are guided by anything that could be described as universal ethical principles.

Politicians will generally act to keep themselves in power by whatever means they think they can get away with. It’s up to the people to stay vigilant to keep them honest.

Are some people trying to produce a module for future PPE courses?

I don’t need an essay in ethics to confirm that lockdowns are deeply immoral, dangerous and injurious to physical and mental health.

Let’s drop all the pseudo theorising and hope that maybe we can get some of the rotten barstewards in court and then porridge for the rest of their natural. Forlorn I know but…

It was the SAGE Team who proposed to scare the bejesus out of the British people in order to gain compliance with their draconian and completely pointless Rules.

We already know that there were people in SAGE who have no understanding of ethics whatsoever (probably most of them). The Minutes of SAGE meetings should identify who proposed and supported using fear as a control mechanism and that person/those people should not be allowed anywhere near Government in the future.

And the Government’s PsyOps Unit must be closed down.

What the minutes (if they exist) will probably not record is the “interests” of the participants. If they all had to declare their interests to the general public when making a presentation, it could have been very different. If they had to do that, they might not have tried it on. Nothing democratic about the politics involved in that group.

Let’s take Bunter as an example. His ethics seem to revolve around his need to be ‘loved’, with particular emphasis on his desire for warm feelings in the vicinity of his wallet and his zipper.