In a recent post for the Daily Sceptic, Toby claims the received wisdom on the Ukraine crisis is basically right, noting that he’s “experienced the unusual sensation of feeling more in step with the mainstream media than I have with my sceptical friends”. While he makes some good points, I don’t think he really steelmans the sceptical position.

Toby concludes by saying that “when a strongman leader uses his country’s superior military force to subjugate an independent sovereign state to his will my natural inclination is to side with the underdog”. But this isn’t the right way to frame the issue. I’m certainly not on Putin’s “side”.

Incidentally, Toby says he supported the war in Iraq, even though that involved a leader (whom some people consider a kind of strongman) using “his country’s superior military force” to invade and occupy “an independent sovereign state”.

The fundamental issue is how to resolve this crisis. The mainstream position – so far as I can tell – is that the West should pour arms into Ukraine while simultaneously crushing the Russian economy with sanctions (or that it should even go to war by declaring a “no-fly zone” over Ukraine).

The hope is that, by adopting this confrontational strategy, either one of three things will happen: the Russians will be defeated or forced to withdraw; Putin will be overthrown in a palace coup or popular uprising; or he’ll be brought to the negotiating table and made to accept terms highly unfavourable to Russia.

While this strategy may work, it seems to me highly risky and potentially counter-productive.

Rather than being forced to withdraw, the Russians may simply fight more aggressively, taking even less care to avoid civilian casualties. This could result in a prolonged insurgency where large numbers of Ukrainians die. And if Putin is overthrown, there could be chaos in Russia – something we don’t want in a state armed with thousands of nukes.

A better strategy, arguably, would be something along these lines: agree to recognise Crimea and the two breakaway regions in the East; and rule out NATO membership for Ukraine. In exchange, Russia must immediately withdraw its forces, and help pay to rebuild the country.

But why shouldn’t Ukraine get to join NATO, if that’s what it wants? The reason is that Russia is a major power, and major powers get to make demands of their neighbours when it comes to matters of national security.

Can Cuba host Russian missile sites if it wants? After all, Cuba is an independent sovereign state. Basically everyone recognises that, no, Cuba cannot do this. In fact, the US would probably threaten nuclear war before the first brick had been laid. (This is more or less what it did during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis.)

Can Venezuela host Chinese air bases, within striking distance of the US? Again, the US would simply not allow this to happen. It has long followed the Monroe Doctrine, which holds that foreign powers must not intervene in the political affairs of countries in the Western hemisphere.

Ukraine is a core strategic interest for Russia, as that country’s leaders have explained repeatedly over the last three decades. There are already US missile sites and air bases throughout Europe. But for Russia, Ukraine is an absolute red line. Attempting to bring it into the Western sphere of influence was always likely to have disastrous consequences.

This point has been made by numerous well-informed commentators on both the left and the right, including: Robert McNamara, Bill Bradley, Gary Hart, George Kennan, Henry Kissinger, John Mearsheimer, Jack Matlock, William Perry, Noam Chomsky, Stephen Cohen, Vladimir Pozner, Jeffrey Sachs, and many others.

But wasn’t Ukrainian membership of NATO “purely theoretical”, in the words of Francis Fukuyama? Not at all. Its intention to join NATO was enshrined in the constitution in 2019. And NATO members consistently refused to rule it out, having agreed in 2008 that Ukraine and Georgia “will become members of NATO”.

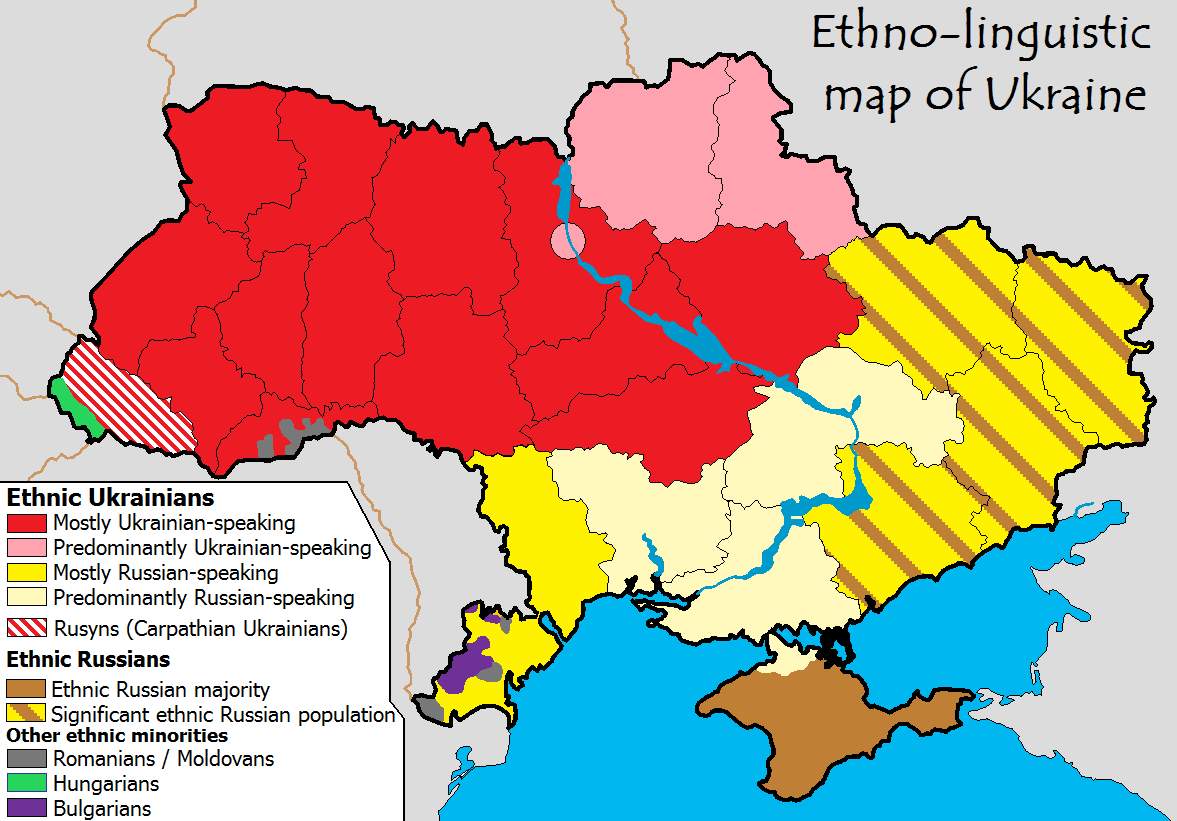

What’s more, Ukraine’s government is considered illegitimate by Russia. In 2014, the country had a democratically elected pro-Russian president, but he was toppled in a Western-backed coup. Since then, the country has taken a distinctly anti-Russian course, banning pro-Russian media and abolishing minority language rights.

Again, none of this is to say I support Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. It’s about acknowledging geopolitical realities, and minimising the risk of catastrophic outcomes like nuclear war.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.