We live in an age of deep incongruity. On the one hand, our public life is increasingly characterised by hubristic claims to be able to subject every facet of creation itself to our will – to master ‘artificial intelligence’ and create sentience; to defeat disease; to manage and control the climate; to transcend biology; to cheat death. On the other, what we experience in our daily lives, as we encounter the world around us, is palpable decline and deterioration – a feeling that civilisation itself is becoming tattered and frayed.

We manage to ignore this odd mismatch between grandiosity and neglect most of the time. But there are moments when the border between the two starts to dissolve and we are able to glimpse some seepage. One such occasion took place for me the other day on a visit to the town centre of Birkenhead, near where I grew up.

How to best describe Birkenhead? It has always been a place with a rough, gritty, seedy streak to it – presumably even when, long ago, it had jobs (it was once a big shipbuilding centre and has a vast, now largely desolate, dockland). I have never known a trip there not to have a feeling of edginess to it; even when I was a teenager with a part-time job at a shop in the main shopping precinct, it felt to me like a place tinged with unease – imbued with an undercurrent of unexpressed malevolence that felt as though it might at any moment erupt into baleful life.

In fairness to it, Birkenhead has some justification for its air of seething resentment. Since the 1960s, when the port began to enter into precipitous decline, it has simply not had jobs worthy of the name – it had an unemployment rate well above 50% by the early 1990s. And although it has some ‘posh bits’ around the outskirts, it must now surely rank, at least statistically, among the worst places in the country in which to live. The North End is one of only five out of 32,844 Lower-Layer Super Output Areas in England to have been ranked in the bottom 100 ‘most deprived neighbourhoods’ in the country for the last 20 years. And other areas of the town, such as Bidston, New Ferry and Rock Ferry, are not in a much better position. As is always the case in down-at-heel places, there are still signs of life here and there, and still plenty of people who ‘burn so bright whilst you can only wonder why’. But it is by and large a hard, mean town filled with hard, mean inhabitants.

At the same time, however, Birkenhead has also always been a place soaked in cultural memories of a time when the average British town felt prosperous, secure, hopeful and confident. Its main park, the first publicly funded civic park in the world, built in 1847, was the inspiration for Central Park in New York and is still impressive. The town is dotted here and there with architectural jewels – the central library; the Williamson art gallery; Hamilton Square (a stunning Georgian square that looks as though it has been plucked out of Edinburgh or Bath); the elegant Town Hall. And there is a strange grandeur to a drive around its grid of wide streets, which nowadays have a bleak aspect (a kind of Detroit or St. Louis in miniature) but still manage to convey the impression that this was once ‘somewhere’.

In short, Birkenhead is in the throes of deep and long-term decline that seems impossible to arrest, but it somehow manages to evoke in the visitor the sense that England was once a country that behaved as though it had a future. It is a place, that is, where people used to have civic pride, and acted on it in the built environment – a place where, for all its current deprivation, a better past can still be glimpsed, if one squints very hard and knows exactly where to look.

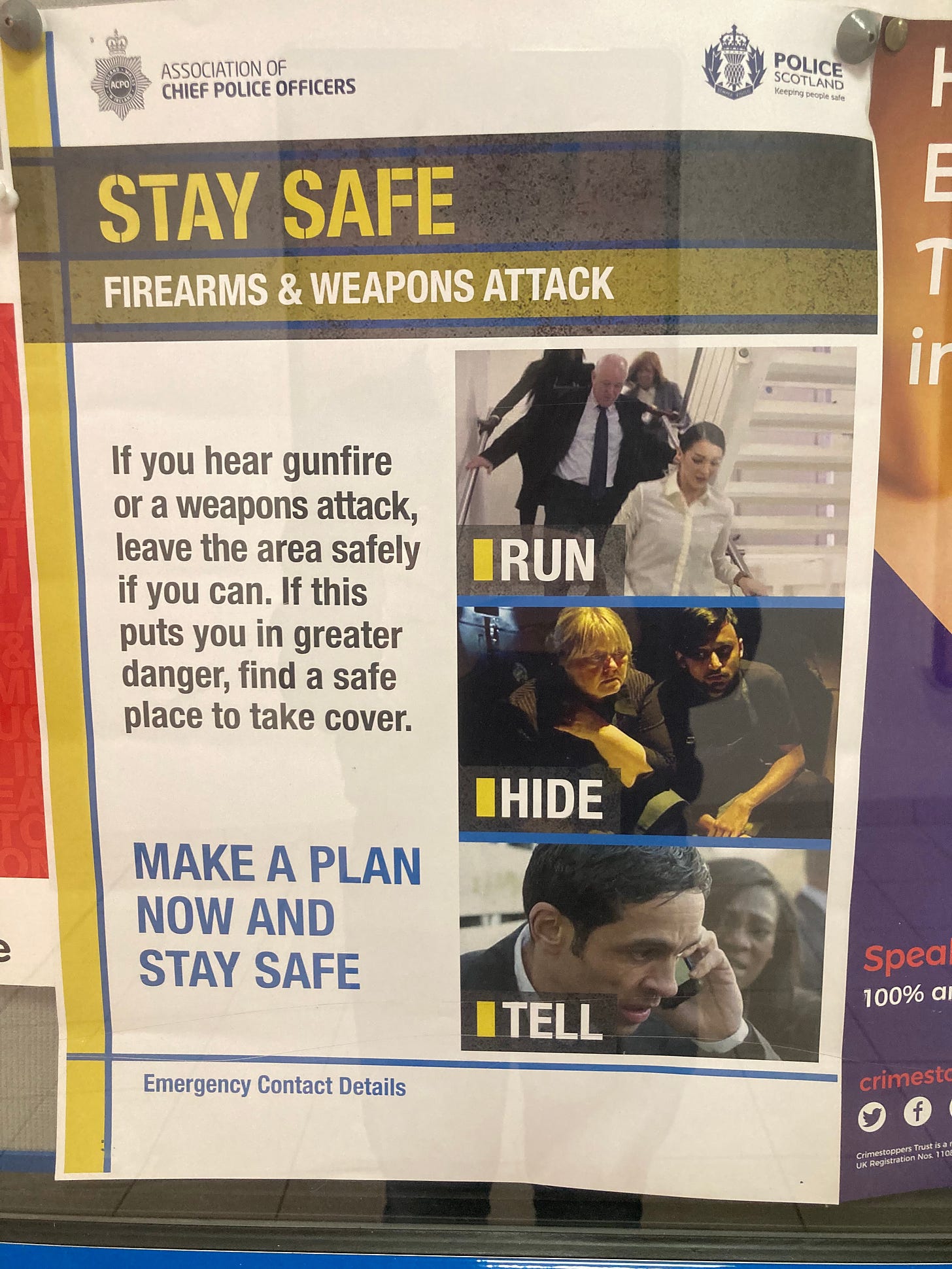

This makes the sense of deterioration which permeates the town all the sadder. It is one thing to go to a place that is impoverished and nasty. But it is quite another to go to a place that was once patently not impoverished and nasty, and yet now is. And the impoverishment and nastiness is getting worse. Birkenhead has never been entirely safe – I’ve seen people glassed and/or bottled there on nights out on several occasions, back in the ‘good old days’ – but it is now the type of town where the local police feel the need to put posters like this up on the main entrance to the shopping malls:

And there is a hard edge even to a mid-morning stroll up the high street. In the aforementioned ‘good old days’, drug use was acknowledged and widespread, but covert. Now, it is in the open. A man was standing in a fugue state outside Boots as I walked past, high as a kite on something – the woman he was with, slightly more awake, managed to summon the energy to call a smartly-dressed man a “cunt”, apparently at random, as he scurried by. (This indeed caused him to scurry considerably faster.) Further on, a crackhead was striding up and down muttering to himself and endeavouring to make eye contact with people around him. A friend, who I met later on, described how he had recently come across somebody shooting up in a toilet cubicle in a nearby bakery; on being roused from his nod by the staff and told he couldn’t do this in their customer facilities the man wiped his bleary eyes and then remarked, crossly, “Where do you expect me to do it?”

The main drag on this particular day was not so much threatening, though, as depressing – a place where the human smile (never mind the ‘please’ or the ‘thank you’) is an endangered species; where people stagger or shuffle rather than walk; where every colour seems to meet the eye after having passed through a haze of grey; where faces seem prematurely aged and withered. The trappings of British urban consumer commercial life, such as it is, were just about clinging on – Superdrug, Costa, B&M, Waterstones, Next, JD Sport, The Works – as though to connect Birkenhead umbilically to the weakening pulse of the national economy. But there were empty units everywhere; I overheard an elderly woman remark to her partner, pointing towards one end of the high street, that “there aren’t even no charity shops up that way no more”.

Also in evidence, as is the case across much of Merseyside, was a generalised acceptance of low-level criminality that one (still, so far) doesn’t encounter around much of the rest of the country. More or less the first conversation I heard, waiting in the queue to be served at a Tesco Express, was a knowledgeable discussion between a staff member and customer regarding the ins-and-outs of identifying a batch of counterfeit £20 notes known to be ‘doing the rounds’. They might for all the world have been chatting about the weekend’s football. There is a sense that crime is a fact of life, a bit like the weather, and which it would be as useless to try to eliminate as would be an attempt to stop the rain from falling; the best that one can do is the equivalent of buying a decent umbrella so as to mitigate its effects.

This was confirmed to me as I ducked into – God help me – the large local branch of Primark. Here, I discovered an innovation. Birkenhead, like the rest of the country, is experiencing a spike in shoplifting. But many of its town centre shops have embraced the march of self-service checkouts – which are annoying and stress-inducing to use, but which have the advantage of not having to have national insurance paid on their behalf or being entitled to an ever-ascending minimum wage. How is one to reconcile the need to prevent and deter theft and the imperative to keep staff costs down? It turns out the answer is to install security gates at the checkouts which literally will not let you leave the area without scanning a barcode on your receipt to evidence your purchase. You are, in other words, in Primark in Birkenhead in 2024 (I assume other branches deploy the same technology) presumptively a thief; it is for you to prove otherwise.

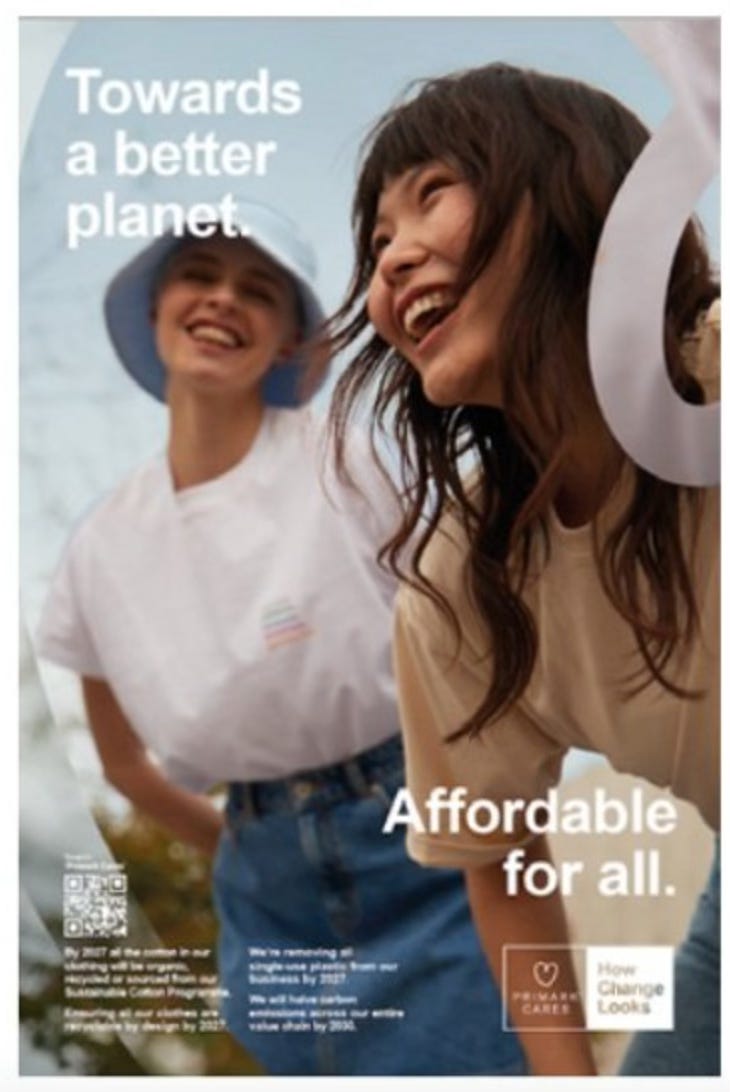

It was impossible not to notice the sheer strangeness of the juxtaposition between the experience of actually being in Primark in Birkenhead and the gargantuan wall displays in the shop itself, which everywhere trumpeted the company’s commitment to the well-being of nothing less than the actual planet:

This, I later learned, stems from a rebrand which Primark recently embarked on, through which it is trying to improve its image through greenwashing and warm fuzzies:

From its website:

We are working towards a better planet. That means helping to reduce fashion waste by making clothes that last longer and can be recycled, using only cotton that’s organic, recycled or sourced through our Primark Sustainable Cotton Programme, and cutting out single-use plastic.

We will work with our suppliers to halve our carbon footprint, using greener energy sources and helping bring back nature with more regenerative farming practices, less water and less chemicals.

We are working to improve the lives of the people who make our clothes. That’s why we’re pursuing a living wage for the workers in our supply chain and creating opportunities for women across our supply chain.

And we will do all of this whilst staying affordable. Because we want everyone to be in on change, so no one is left behind.

Using our scale and low prices for good.

Towards a better planet that is affordable for all.

In this, though, to be scrupulously fair, Primark is only following current trends, wherein ‘the planet’ is presented as something that is simultaneously threatened by the very existence of human beings, while at the same time being something that is conceived as a field of improvement – something to make ‘better’. Never mind that ‘the planet’ proper will still be here billions of years after we are gone and that we are about as relevant to its ongoing existence as a few grains of sands being blown about on a beach. The phrase has become a kind of catch-all term for human existence – what is ‘good for the planet’ essentially meaning ‘nice things that give us a warm glow’ and what is ‘bad for the planet’ meaning anything which one ought to be ashamed of (the exact nature of the source of shame fluctuating from moment to moment). A quick Google search reveals it being used by other fashion retailers such as River Island and Shein, and in the context of construction, fitting out and refurbishment, beverages, flat-pack furniture, retail banking and flooring. You can even find out how to communicate science for a ‘better planet’ with an MSc at one of the nation’s leading universities. Naturally, politicians love the expression, and Eurocrats yet more so – a few years back we were treated to a trial balloon for the slogan ‘make the planet great again’ (it didn’t catch on).

There is something almost frighteningly perverse about a society which contains places in it that look like the North End of Birkenhead and yet whose elites can barely shut up about their asinine commitments to making the planet better. Britain is, manifestly and with alarming rapidity, declining. The rapidity is not evenly distributed, and there are big islands of bourgeois security (many of them not more than 15 minutes’ drive from Birkenhead town centre) where it is still possible to have a wonderful time sipping expensive IPAs in hipster pubs that serve food that includes ingredients like kale.

But in every respect one can think of – in terms of its economy, education system, physical infrastructure, birth rate, public health, crime rate and standard of living – the country is getting worse. We do not seem, collectively or individually, to have any ideas whatsoever about how to stop this decline, let alone reverse it, nor the wherewithal to put such ideas into effect. At times, it seems like we can barely tie our own shoe laces anymore. And yet we have the gall to describe ourselves as working to improve the planet as such. What does one say about such a country as this?

When I was a child, I used to page through an old copy of an Arthur Rackham-illustrated edition of Aesop’s Fables (1912), with an introduction by G.K. Chesterton, that sat on my parents’ bookshelf. The closing paragraph has always stuck with me. It reads as follows:

Man, in his simpler states, always felt that he himself was something too mysterious to be drawn. But the legend he carved… was everywhere the same; and whether fables began with Æsop or began with Adam, whether they were German and mediæval as Reynard the Fox, or as French and Renaissance as La Fontaine, the upshot is everywhere essentially the same: that superiority is always insolent, because it is always accidental; that pride goes before a fall; and that there is such a thing as being too clever by half. You will not find any other legend but this written upon the rocks by any hand of man. There is every type and time of fable: but there is only one moral to the fable; because there is only one moral to everything. [Emphases added]

This is a statement sure to outrage any anthropologist, classicist or comparative religionist. But we are, have no doubt, currently living out its essential message, and seeing its truth unfurl before us in real time. A society can for some time be ruled by a class of people who tell themselves that they are making the ‘planet’ better while the day-to-day, ‘lived experience’ of ordinary people in that society gets worse and worse. But it cannot go on that way indefinitely. Eventually, the only moral to everything will reassert itself, pride will be followed by a fall, and the insolence of the superior will be revealed – probably painfully.

It is to be hoped that this will happen through the ballot box. But I don’t take it as a racing certainty. At the moment, the gambit which everybody in our chattering classes seems to be banking on is that, by some miracle, making ‘the planet’ better will also make life better on Birkenhead high street, through vastly improved productivity achieved with AI; through green jobs, cheap energy, etc.; through a promised end to the bugbears of mainstream middle-class culture circa 2024; and through a rehashed, souped-up, activist State. I don’t know that there are many normal people who really believe any of this, least of all the population of Birkenhead. But when even this desperate fantasy is demonstrated to be false there is going to be a crisis – and a confrontation. And one suspects that the subsequent demonstration of Chesterton’s truism – that there is such a thing as being too clever by half – is not going to be at all pretty. In this respect at least, though, the people of Birkenhead are well-prepared. They’ve been living through a slow-motion crisis for generations.

Dr. David McGrogan is an Associate Professor of Law at Northumbria Law School. You can subscribe to his Substack – News From Uncibal – here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

If you follow one Substack, make it David’s – “News from Uncibal”.

His articles on the hell we are descending to are spot on, and his prose is excellent.

They don’t give a toss about Birkenhead!

Or “the planet” for that matter.

Nobody cares about ‘the planet’, even/especially people who say it is their prime concern

I think that’s broadly true. I think in the little things I try to avoid wantonly wasteful or destructive behaviours because they seem wrong to me – I guess that “helps the planet” but that’s not really how I think of them. I would be against concreting over the entire planet, killing every living thing except us, that kind of stuff – but none of those things are likely to happen. I tend to think that if humans are left alone to get on with things, we will find a sensible approach to “the planet” – the population looks like it will settle down or maybe even reduce eventually, and we will make more efficient use of the resources we have, and find new ones.

As a rule of thumb, I don’t trust people that claim to want to help people they don’t personally know. And even less so people that claim to want to make the world a better place. At best, these people are completely delusional about their capabilities.

Charles Dickens would have agreed with you.

The people who claim to want to “save the planet” couldn’t just care less if Birkenhead and it’s inhabitants sank into the sea never to be seen again. Deep down, they’d actually prefer it happened.

Tell me I’m not right.

You’re basically right, although some genuinely convince themselves that they care (an aspect of their delusional nature). And btw “its” not “it’s.”

What a stupendously good article; well-written and perceptive. Unfortunately, under the present Government I can only see Dr McGrogan’s more pessimistic observations becoming unpleasantly true.

God help us all.

You have said it for me.

Probably Dr McGrogan’s best article for DS. Sadly, I was quite able to transpose Oldham for Birkenhead. Our town has been in decline for over thirty years and ably abetted by a Labour run Coucil which is all but the definition of a mafia outfit. Over the last five years we have seen a massive influx of brown and not so brown skinned Gimmigrants and the town centre is now nothing but a slowly evolving Bangladeshi bazaar otherwise known as a shit hole.

Long gone are the days when Platt Bros ran the biggest engineering plant in the world employing over 15,000 people over many acres and when Oldham was rightly celebrated as King Cotton.

To say I am filled with hate for the politicians of the last twenty five years would be an understatement.

Frank Field ….. one of Labour’s more respectable MPs and sadly no longer with us ….. represented Birkenhead for years. He managed to do nothing to stop the decline.

There isn’t a hope in Hades of the Champagne Socialist Student Union Marxists currently in Government doing it.

“Britain is, manifestly and with alarming rapidity, declining.”

Absolutely. You have to be blind not to see it.

You can see in even in the affluent areas. I live near Cambridge, a high-tech growth area. Go for a walk in the city centre after the shops close and look around.

Yes, this is a sharply accurate but very depressing piece of writing. But how can the people in charge of our country not be aware?

I am sure “the people in charge” are more than aware. Actually I imagine they would regard articles such as this as an emblem of their success.

Agreed – they are aware, and they don’t care

I live in a fairly affluent area in the West Country. My immediate area still resembles the England-of-old although we are now steadily “being enriched” by “diversity” …. most of which, I suspect, is claiming welfare judging by their appearance.

If you venture into the local main town centre the decline is obvious and much the same as elsewhere in the country: boarded up shops; beggars on the streets; “diverse” Big Issue sellers a low-level air of menace.

It’s only a matter of time …..

A superb article indeed.

But how tragic it is necessary.

‘Why Is Labour Focusing on Saving the Planet?’

It isn’t.

It is stealing your money, your liberty, your energy, ability to travel and – by dropping voter ID – your democracy.

Can we start calling Starmer’s reign what it really is please?

“We do not seem, collectively or individually, to have any ideas whatsoever about how to stop this decline, let alone reverse it, nor the wherewithal to put such ideas into effect.”

For me the place to start is secondary school education, whose dire state (for the majority) is captured by the BBC series “The 4 o’clock club”, where the cool kids are the ones that get detention, and where the star actors get jobs as hairdressers and caretakers when they get too old to be pupils.

The other side of the coin is that you get to be one of the elite by going to uni and “studying” some enjoyable but useless subject such as ancient Greek poetry.

Studying PPE is very popular especially if you skip the E lectures given the stupidity of our politicians.

Thank you Dr McGrogan. Over 40 years ago I was at Liverpool University in a department that overlooked a demolition site. Bricks and rubble remained unmoved for three years. Students I knew lived in terraced houses with front doors opening to ripped wallpaper hanging off walls swathed in damp and mould.

I’ve only been back to Albert Dock since – much changed from the decline and dereliction of 40+ years ago. I once took the ferry across the Mersey, but only got as far as Hamilton Square.

I played cricket in Sefton Park and travelled to away matches at clubs like Formby, Hightown and Neston, prosperous localities where senior university academics tended to live. I’ve revisited cricket grounds on the Wirral in recent years and the ambience seems relatively unchanged.

Then, as now, two utterly different sets of enclaves existed. From family history research on the urban area I originate from, I’m getting the impression prosperity and poverty co-existed in closer geographic proximity in the eras before the Second World War.

I digress. You’re quite right – for want of a better term, the governing classes are more wedded to sluicing away public money on tilting at windmills than on improving the lot of the governed. As ever, follow the money.

Groupthink abounds. Higher education seems rife with it. Let’s all feel world-leading about spaffing another £22 billion on sequestering the trace atmospheric gas essential for life on earth.

Betrayal of an unspoken fundamental hippocratic oath of government.

I had to spend a day in Birkenhead. The only shop we could find was a Kwiksave. It had no windows, security men, but no fresh food whatsoever. For the nearby high-rise flat dwellers I guess it was the sole source of sustenance. One of the most deeply dispiriting days of my life.

The Planet™ is a distraction. What Labour is really doing is extract money from the British public to make Labour donors like Dale Vince insanely rich and for political pet projects of the UN. They like to claim that they need to save the planet (certainly no megalomania here) because they want to avoid that people notice that they’re really just making Birkenhead etc an even worse place and absolutely intentionally so.

Members of the arrogant, virtue-signalling, hypocritical Westminster Uni-Party and the wider Establishment would do well to read Kipling’s poem “The Beginnings” ….. better known as “When the English began to hate.”

Obviously they’d have to hold their snobbish little noses first and they’ll need counselling afterwards, but they’d do well to pay attention ….. because those are the circumstances they’ve created.

You could say the same about most other towns in the North West whose industries, hence their entire raison d’etre, have disappeared. If you think Birkenhead’s bad, take a walk down Fleetwood’s high street on an average Saturday afternoon. I do the walk not to window shop the boarded up units, charity shops and fast food joints but because I refuse to be intimidated by the roaming drunks and smack heads, I cling on to the memory of when it was a good place to live in. It must be terrifying for old ladies and women with prams though so onward and downward the plug hole go the last flickers of commercial life.

I too hope for a peaceful resolution to all this. We always manage one eventually but how long can cheap heroin and booze keep the lid on the volcano of wasted lives?

I really don

t recognise the negative description of Birkenhead. I was shopping in the town centre just after Christmas and it was a pleasant experience. All the main banks are still there. I live in West Kirby, a prosperous seaside town on the opposite side of the Wirral. I moved here 30 years ago and we had 6 banks, we now have none. The North End I drove past is mainly smart new housing; the council has just relocated many of their staff into 2 new office blocks right in the town centre which should be a boost to local business. Yes, there are a fair few vacant units but everywhere was clean and well swept.t see any beggars or homeless tents which are in great evidence in other town centres. Hate to sound like a Wirral Council PR chap but I am only detailing what I see. As a near 70 year old I wouldn`t go near the place if it was anything like the author of this piece describesI didn

One of the most perceptive articles I’ve read in a long time. Similarly, Sandown, IoW, just a few short miles from the affluent town of Cowes, is a run-down, depressing slum. It sounds very like Birkenhead. Hard to explain why such degradation should exist on what is a relatively prosperous island.