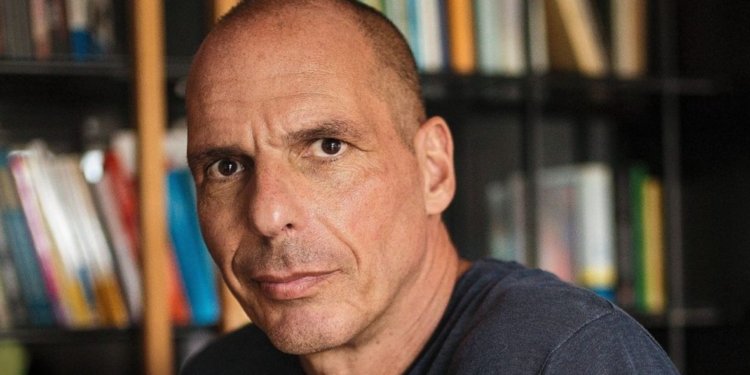

Above Das Kapital there is another system. And this is the system we live within. So says Yanis Varoufakis.

Varoufakis is an admirable figure. He is Greek, knows his Homer and Hesiod. But he is also very English: in the sense of having found his way in the world by using the English language (as well as a motorcycle). His latest book Technofeudalism is unusual in that its range of reference is such that it will appeal to readers in the United Kingdom. Finally, he is an economist. He has written a textbook on economics, and knows his rent from his profit, and can talk derivatives. This means that he is in cloud-cuckoo-land – that’s a reference he’ll enjoy – as far as I am concerned, since my grasp of economics is that of a 12th-century monk. In the 1980s I used to marvel at the habit politicians had of talking about inflation and interest rates as if they knew what they were talking about. Niall Ferguson and Adam Tooze become strange shamans as soon as they click into the language of finance capital. But I still think it is worth knowing what is going on, and what our cloudcuckooists think about what is going on.

The book Technofeudalism is worth a read. Varoufakis has a hypothesis, and it is a very interesting one, which is clear enough to a careful reader, though I think Varoufakis slightly botches his exposition of it. Let me explain.

The hypothesis is about economic history. Varoufakis operates with a sense of history that is fundamentally Marxist. Hence: stage 1 is feudalism, stage 2 is capitalism, stage 3 would have been communism if anyone had constructed communism correctly, so [algorithmic correction] stage 3 is now “cloud capitalism”, as he sometimes calls it, or “technofeudalism”. In short, and most simply, Varoufakis claims that we no longer live in a capitalist world. So all the fools who blame everything on capitalism and neoliberalism, though they were correct 20 years ago, are now out of date. The game has changed.

In slightly more detail, his sense of history is derived from the post-war consensus. Its crucial dates: stage 1 is from 1945, when the Bretton Woods system was imposed on the world, stage 2 is from 1971, when Nixon ejected Europe and Japan from the dollar system, and stage 3 is from 2008, when the system established in the shadow of Nixon fell apart, giving rise to cloud capitalists and technofeudalists. This story is interesting, and instructive, and Varoufakis has been talking about the first part of the history ever since his book The Global Minotaur, which was about stage 2. He has now brought us up to Stage 3.

Let me say a bit more about each stage. As far as I understand it, Bretton Woods was achieved over Keynes’s almost dead body. What Keynes had wanted in 1945 was a system which would automatically balance trade surpluses so that capital would continually be redistributed through flows of money against those surpluses. (Even here I may be garbling things slightly. Never mind.) Bretton Woods ignored Keynes: since the United States, though generous, was not that generous, and did not want to sacrifice its sudden arrival as Top Nation. What the Americans did therefore was to lavishly distribute dollars around the world, especially to Japan and Germany under the banner of ‘reconstruction’: and since America was the industrial and technological centre of the world, Germany and Japan used their dollars to buy American commodities. This is the grand era of America First. That is stage 1. Varoufakis has mixed feelings about it: on the one hand, he dislikes it, as it was not communism. On the other hand, it was better than any obvious alternative: for instance, it allowed the “liberal individual” to flourish (a good thing, as far as Varoufakis is concerned).

Stage 2 was even more miraculous, since what happened was that America lost its position as dominant manufacturing nation. It lost its trade surplus, when German and Japanese industrialisation caught up and overtook American industrialisation. But the United States engineered a system that enabled it to remain dominant, by ensuring that all exchanges took place in dollars – the reserve currency of the world – so that all profits acquired in Germany and Japan ended up in America on the New York Stock Exchange: in effect, paying for American Government, American military, American culture: all that continued post-Golden Age Hollywood stuff of the 1980s and 1990s. This was all dignified by the fact that the Cold War dragged on; and after the end of the Cold War it carried on with a bit less dignity.

Stage 3 is when this system had its comeuppance: first, in 2008, when the financial crisis caused by excessive investment slicing and complicated computer-generated derivatives created a situation in which any simultaneous default would reveal that the banks had no clothes and the citizens had no houses. Hence Gordon Brown and other luminaries stepped in and lubricated the system by printing money: saving the banks and, alas, Varoufakis says, also saving the bankers. This happened again in 2020, when governments stepped in with much printing of money to save the situation. Now we live in heavily mortgaged world, heavily dependent on a future, or ‘futures’, of someone doing some work later on to pay for what we are spending now. Anyone who follows the logic must suppose that the future is all but bankrupt.

But there is something else operating in stage 3, and this gives Varoufakis his leading concept of “technofeudalism”. For Varoufakis maintains that over and above the capitalist system has emerged a system of cloud capitalists running corporations that are not capitalist but something else. They are not capitalist because they are not interested in profits. They are interested in what he calls rents. He instances, on the one hand, the vast rent-seeking investment companies BlackRock, Vanguard, State Street (which own everything in sliced form) – they are the petty überkapitalisten – and, more significantly, the vast platform corporations Amazon, Google, Apple, Twitter etc. that are the true technofeudalists. Varoufakis has noticed that Amazon and the rest are not interested in profits. They are not creating commodities to sell so much as they are creating worlds or frames within which everyone else, including the capitalists, are forced to live, always surrendering a part of their income in the form of what Varoufakis calls “rent” but which we could call “tax” or some other words. He hypothesises that we are all about to become either cloud proles, working in factories for one vast corporation or another, or cloud serfs, feeling free, but in effect working voluntarily by producing applications or content or transactions that generate rent for not only Amazon, Google, Apple, Twitter, Instagram, WhatsApp etc., but also Tencent, Alibaba, Baidu, Ping An and JD. One side effect: we have a new Cold War between American corporations and Chinese corporations. Another side effect: these corporations have our data and our identities: and we voluntarily surrender these through our willingness to offer our attention to algorithms that twist and turn our behaviour as they (and we sheepishly) please.

There’s the dystopian vision of the world he sketches. It’s a good one. But I have one complaint about it. This is that Varoufakis does not understand feudalism. He continually misuses the word ‘fief’. And he seems to think that feudal lords extracted rent. This is not what they did. Feudalism was a system of reciprocal right, whereby lords offered land in return for service, especially military service. No one since the 17th century – when feudalism was first studied by Spelman, Brady and others – has ever thought feudalism was perfect. It was violent, even barbaric: it depended on force (Norman castles in England etc.) But it related lord to vassal in reciprocal manner: it suggested that the lord had to take some notice of the vassal. It sketched a primitive form of accountability. And it generated the first representative institutions: Parliament, for instance. That’s another story, but Varoufakis would do well to understand it a bit better. It was service, not rent, Yanis, that the lords wanted.

Apart from that, one can also argue with his politics. He sketches his dystopian modern financial history, and ends by suggesting that we need to restore the commons: and his suggestions here are as airy and vacuous as one could desire. (We could call his scheme ‘universal basic shareholding’.) Fair enough: no one knows what to suggest. But he is certainly right in his major claim that capitalism continues to exist and yet has been subjugated to a higher system. I’d call this higher system Überkapital. Some people are already calling it this. Marion Fourcade, for instance. The botching of the argument I mentioned above is that Varoufakis sometimes likes to suggest that capitalism is dead or withering away, or whatever (the subtitle of his book is the misleading What Killed Capitalism), but what he actually means is that it is alive and well but no longer in charge.

- Feudalism = landlords were in command (maintained by rent).

- Capitalism = capitalists were in command (maintained by profits).

- Technofeudalism, Überkapital, what you will = cloudcapitalists are in command (maintained by ‘cloud rent’ or cloud tax).

In other words, we now live on platforms. And the platforms are fundamentally private, not public. Otherwise everything goes on as before: like Russian dolls, we have capitalism inside technofeudalism, and feudalism inside capitalism, and lived life inside feudalism.

Maybe this is all in The Wealth of Nations and we are still writing footnotes to Adam Smith. Smith wrote that high wages require a “progressive state” (like post-war America). By contrast: “The stationary state is dull; the declining, melancholy.” Plus he spoke of “the monopoly of the rich, who, by engrossing the whole trade to themselves, will be able to make very large profits”. He wrote all that in 1776. Perhaps Varoufakis would only want to add to this: “Rents, not profits.”

There are some false notes in Varoufakis. He mocks Musk, and seems unable to believe that Musk might genuinely believe, even if unsteadily, in the importance of free speech. We all lived through “the nightmare” of Donald Trump, he says. We are ruining the world in climate change by depleting the commons. He has a fatuous down-with-the-kids side which is tainted in Greta hues. He refuses to think about subjects he does not understand. I wonder whether he thinks his audience is composed of ordinary soft-shoed centrist Dads and machine Feminists who lean Labour and Democrat and Blob and Taylor Swift: he writes in order to wake them up. Well, good luck, and all that, but these unthought-out asides about politics rather weaken the sharp analysis otherwise in evidence. Yet Homer nodded, so I suppose we can allow Varoufakis to take a nap too.

Anyhow, let’s exult in the hypothesis. Our overlords in government have slept through a major change in world finance. We all exist, some of us reluctantly, in a world of algorithms and search engines and platforms, and all our economic transactions are being sucked into a weak Western simulacrum of a centralised digital currency world. Maybe this is not as bad as Varoufakis suggests. He suffers from a delusion of the possibility of secular escape from the world order. Some of us do not. Escape for us is religious, or aesthetic, or inward. And there has always been hierarchy and extraction, ever since the first Sumerian ziggurat. So perhaps there is nothing to be done about that. But it is worth knowing what is going on, and Varoufakis’s is the most persuasive account I have seen. Everyone else, by contrast, is simply Roming about while their fiddles burn.

Dr. James Alexander is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at Bilkent University in Turkey.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.