It would be necessary for a university to advertise itself as pursuing a particular purpose only if it were talking to people so ignorant that they had to be spoken to in baby-language.

Michael Oakeshott

The new U.K. Government has wasted no time in transmitting its intentions with respect to universities: they are going to be transformed into an arm of the state, and their purpose is now simply going to be the achievement of the state’s purposes. A single, short written statement issued to Parliament last Friday by the new Secretary of State for Education, Bridget Phillipson, makes this all perfectly clear. And as a result it therefore represents very neatly what I referred to in a recent post as the “moral enormity” of the kind of purposive Government which Labour always pursues when in power.

Much media commentary on the statement has focused on Phillipson’s announcement in it of her intention to delay the commencement of an Act which came into effect only last year, under the previous Government, and which was about to become active in most respects at the beginning of August. This is the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Act 2023, which was enacted in order to try to prevent the kind of censorship, cancellation, de-platforming and mobbing which increasingly goes on at universities these days, and which would have worked by creating a statutory tort permitting academics, students and invited speakers to sue universities for failing to secure their freedom of speech.

Phillipson has now well and truly put the kibosh on that idea (to use the technical term). Owing to the fact that most of the provisions of the Act only commence on the say-so of the Secretary of State for Education, and since said Secretary of State is now of course Ms. Phillipson, it is in her power to delay commencement indefinitely. Since she has not put a date on the duration of the delay she has announced, and since she has said that during it she will be considering all options “including repeal”, it seems pretty obvious what will happen. The Act is no more – it is an ex-Act. Cue Monty Python impressions.

There is plenty of noise being made about this, and a number of commentators have described it as a “declaration of war on free speech“. And no doubt it is troubling, if for no other reason than that a Government Minister should as a matter of constitutional principle not be using powers which she technically possesses to subvert the settled will of the legislature. But I have nowhere seen picked up for analysis the content of the rest of Phillipson’s statement, which may in the long term prove to be much more important, and which in any event puts the decision to shelve the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Act in a rather different context.

You see, Phillipson also took the opportunity on Friday 26th to announce the publication of the conclusions of an independent review of the Office for Students (the U.K.’s higher education regulator, or OfS), titled ‘Fit for the Future: Higher Education Regulation towards 2035‘. This review, penned by somebody called Sir David Behan CBE (more on him in due course), is intended as a “forward-facing strategic review” of U.K. higher education regulation in light of a “rapidly developing global debate on reimagining the nature and purpose of higher education”.

What is interesting about this review is not its concrete recommendations, which are a combination of snore-fest and statements of the obvious (“the OfS [should consult] the sector when implementing changes to regulatory methods and then [pilot] such approaches before formal roll out”; “the OfS [should contribute] to the overall improvement of the higher education system”), but rather for what one might call its enabling function: this is a document that is designed to build the case for much more direct Government control of universities, achieved through the OfS itself.

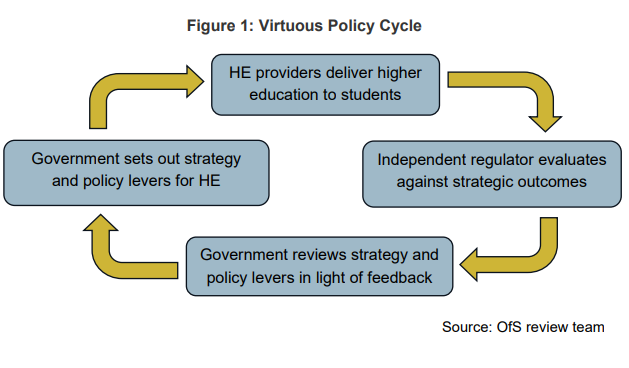

Hence it is not the recommendations that we really need to pay attention to, but rather the message, reinforced throughout the review, that there is “a clear role for Government as an active player” in “shap[ing] higher education teaching and research for the future”. Thus, Behan envisions a “virtuous policy cycle”, wherein “Government sets out its strategy for higher education and the policy levers it intends to deploy to achieve strategic outcomes” and universities respond:

Elsewhere, he describes Government as nothing less the “architect of the higher education system”, and posits the role of the OfS as being an “active collaborator” not just with universities but with the Department for Education and the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology – all pulling together in the same direction and towards the same ends. He even goes out of his way to address the complaints – let’s call a spade a spade: the whinges – from universities that under the previous (Conservative) Government, Ministers (and the OfS itself) were sometimes a bit too confrontational: they used nasty, hurtful rhetoric like “poor quality HE” and “robust investigations”. In the new era, there will be none of that – the OfS and the universities will have a more “confident, trusting, and respectful relationship”, working hand-in-glove to improve quality and equip U.K. society to face the future.

This all gives the lie to the notion that the OfS will be particularly “independent” of Government. That word appears again and again throughout the review, in a “the regulator doth declare her independence too much” sort of way; in truth the intention is clearly the opposite. Government will set out its “strategy” and pull “policy levers”; universities will respond; and the OfS will monitor exactly how they do so and give “feedback” to Government. This is not about independence so much as plausible deniability: when things go wrong it will doubtless be the OfS’s fault, but in normal times its role is clearly not being envisaged as that of an external auditor. Its job will be to make sure that when Government tells universities to jump, the only question they will be asking is “How high?”

This is all confirmed by the amusing (well, amusing if it was happening in Turkmenistan or Honduras) way in which the review was received by Phillipson and what has happened subsequently. Sir David Behan CBE, it turns out, has, after submitting his review, just been appointed to be nothing other than the interim Chair of the OfS by Phillipson “to work with the current executive to implement the recommendations of [his] independent review” (this was indeed announced in her statement of July 26th). He gets this plum position, she declares – almost in as many words – because his review’s “core analysis” chimes with what was in the Labour manifesto for the 2024 election.

If I was a very suspicious and cynical investigative journalist I might find it curious that Sir David penned an independent review that just happened to be very pleasing to an incoming Government, and delivered it a mere three weeks or so after said Government took office – and that his reward for this just happened to be an appointment to a nice warm toilet seat within the relevant regulator. But I am sure everything about the process of his appointment was entirely above board. What is important is not that there is any scent of fish in the air whatsoever here – there is none at all that I am able to detect – but the message that all of this sends: Phillipson likes Behan, and this is obviously because Behan’s review says that, in effect, universities are now basically supposed to just do what Government tells them. They’re not supposed to worry their pretty little heads about the purposes of education and academic research, because Government will tell them what those purposes are. Their jobs is really just going to be the implementation of educational “strategy”.

There are three things to say about this.

The first concerns what exactly Government will tell universities to do. What strategies will it lay out and what “policy levers” will it pull? Well, perhaps it helps to note that our friend Sir David Behan CBE, the new interim (and no doubt soon-to-be-permanent) Chair of the OfS, has never had a prominent position in university management or governance nor, I think, ever taught at a university. But he has, according to his biography “held several non-executive director and advisor roles with a number of public and private organisations across the health and social care system” and sees his own career as having had a “golden thread” running through it: namely, a “commitment to mak[ing] a contribution to a more socially-just [sic] society”. This is obviously, then, the way the wind is blowing: not so much academic rigour or the pursuit of truth, but instrumental teaching and research in the name of social justice. That, it seems, is how the purpose of universities will be increasingly construed.

The second is the emphasis which both Phillipson, in her statement, and Behan, in his review, lay on having “stability” and “financial sustainability”. Clearly, with U.K. universities in the round feeling a squeeze, this is at the forefront of everybody’s minds. But Behan’s framing of the issue is instructive:

Many providers [he basically means universities] are critical research and innovation assets, forming part of the U.K.’s strategic research capability, in which Government made significant investment to developing infrastructure, staff and facilities. Further, many higher education providers have a teaching focus or specialisation. Some are anchor institutions, rooted in ‘place’, serving the educational needs of their community, providing employment, fostering economic well-being and social cohesion.

This means that, “as [the] architect of the infrastructure of the higher education system” the Government “should consider whether the prospect of such a provider exiting the market is conducive to a more strategic organisation of higher education in England” and that it “should also consider whether… noninterventionist positioning” is “still appropriate for meeting the challenges of today”. The subtext here is easily parsed: universities will get the financial stability they crave and more “interventionist positioning” (read: too big to fail), but in return Government will get its “more strategic organisation of higher education in England”. Universities can hardly complain about the instrumentalisation of their activities which will follow: if Labour is going to fund their ongoing existence, then Labour is going to get its pound of flesh; this is as inevitable as day following night.

And the third thing to say is about freedom of speech. It is absolutely no accident that Phillipson took the opportunity to announce the publication of Behan’s independent review, his appointment as interim Chair of the OfS, and the effective cancellation of the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Act 2023 all in one fell swoop – because all of these things are related. If Government is going to take more direct strategic control of universities in order to achieve whatever purposes it has in mind, then it necessarily follows that the last thing it will want is pesky academics who won’t get with the programme causing trouble. To repeat the point I made in my post the other week, when the state is imagined to have purposes, then it must follow that the population lose their freedom, because their acting against the State’s purposes, once it has them, is intolerable to it. The population in such circumstances are reduced to the status of conscripts in the state’s cause, and conscripts are not supposed to be able to say whatever they like about the cause into which they are being conscripted. They are free to say whatever they like as long as it aligns with the state’s purpose. So why on Earth would we expect the current Government – a purposive one par excellence – to commit to securing freedom of speech for academics?

But another important message was sent by Phillipson’s decision to “delay” the commencement of the Act. The point about the Behan appointment is that it is all very cosy – it is, remember, supposed to establish a “confident, trusting and respectful relationship” between universities and the OfS. Behan is obviously sympathetic to the Labour Party and his aims clearly align with those of Phillipson, but there is nothing really very unusual about that in the context of U.K. higher education, where support for Labour is almost monolithic and any dissatisfaction expressed with Labour policy tends only to come from further Left.

And most academics in the U.K., it must be said, would not have been fond of the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Act. They would have seen it as a shield for right-wing nutjobs, racists, bigots, Christians and gender-critical feminists, and as such they will be very glad to see the back of it. What we are seeing here, in other words, is not so much a declaration of war on free speech so much as a declaration of friendship from a Labour Government to one of its most loyal voting blocs: vote for us and we look after your interests, in this case by waving a green flag to the rooting out from campus of anybody whose speech makes the mainstream Left uncomfortable.

There is nothing really puzzling or surprising about this; it is the way that the Labour machine always operates. Vote for us and you get sweeties – vote Tory and we’ll give you a smacked bottom (usually in the form of tax rises on the blocs of the population who generally vote Conservative – pensioners and people who send their kids to fee-paying schools being the whipping boys this time around). The sweetie is in this case not having to worry about occupying the same physical space or the same profession as somebody who lacks the Right Opinions. And let me tell you – I know these people – the coming repeal of the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Act will be very popular amongst a great many academics in the country for precisely that reason.

The future of higher education, though, is in any case clear. It seems likely that enough money will be found from behind the Government’s sofa to keep the show on the road, so in that sense things look, in the short to medium term, relatively rosy. But change is afoot. For a very long time universities have had to play an awkward balancing game in which they have tried to pursue their own interests while under increasing pressure from Government to justify their (comparatively lavish) funding by demonstrating that the research they produce has real-world value.

It seems that this game is now coming to an end, and that the resolution has (inevitably) been worked out in favour of Government: there will go on being such a thing as ‘higher education’ and there will still be such a thing as ‘universities’, but they will increasingly resemble state-directed research institutions, teaching state-directed education. This will not likely be a coercive transformation, but – as is so often the case nowadays – oriented around nudging. Funding (except in the hard sciences) will dry up for any type of research that does not have an explicit ‘social justice’ dimension; course curricula will be to a certain extent dictated by externally-imposed requirements; scholars will be put under increasing pressure to present their work as furthering some cause or other in the name of ‘impact’.

Working academics will have to find ways to go with that grain while maintaining their commitments to their profession and their students; consequently, good teaching and good research will continue to get done. But university as it was once understood – a community of scholars engaged in the pursuit of truth – will simply depart from the scene. What will remain will increasingly resemble an extension of school, designed to educate a workforce that will suit the imperatives of the state; something that is instrumental, purposive, technical, prescriptive. This will be a great shame and will not work even on its own terms. But beggars cannot, I suppose, be choosers where messes of pottage are concerned, and the signal being sent to universities by Phillipson and Behan is in this respect as clear as day: Government will cross your palms with silver, but Government will want due consideration. And this will mean “interventionist positioning” in many more ways than one.

It probably goes without saying that the views expressed here are my own and do not represent the position of my employer.

Dr. David McGrogan is an Associate Professor of Law at Northumbria Law School. You can subscribe to his Substack – News From Uncibal – here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.