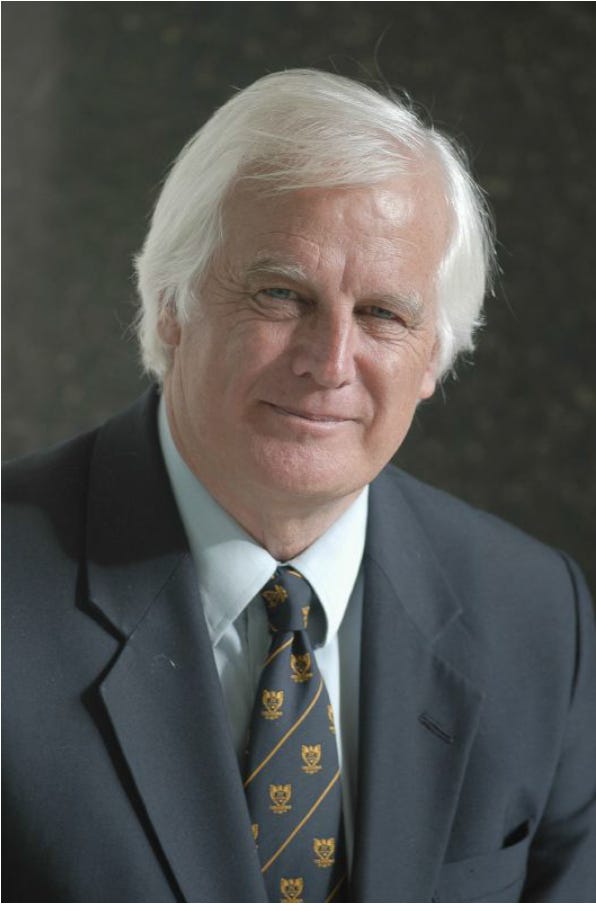

“Don’t believe what Wikipedia writes about me,” Professor Ian Plimer emails me when I arrange an interview with him. Of course, the first thing to do in this case is to check the Wikipedia article about him. “Ian Rutherford Plimer (born February 12th, 1946) is an Australian geologist and Professor Emeritus at the University of Melbourne. He rejects the scientific consensus on climate change. He has been criticised by climate scientists for misinterpreting data and spreading misinformation,” are the first sentences of the Wikipedia article about him.

Plimer is indeed an Australian geologist and Emeritus Professor of Earth Sciences at the University of Melbourne, where he once was Professor and Head of Earth Sciences. During his long academic career, he has also been a professor at the University of Newcastle, University of Adelaide, Ludwig Maximilians Universität in Munich, Germany, and has work relations with several other universities. He has published more than 130 scientific articles and was one of the editors of the comprehensive five-volume Encyclopedia of Geology. Of course, not all of this information needs to be included in the first paragraph of the Wikipedia article about a renowned scientist, but the editor’s choice to include a clear accusation that Plimer is somehow linked to “spreading misinformation” is not surprising, to say the least.

Wikipedia’s ‘tiny’ error

The humorous thing is, however, that the editors of the Wikipedia article about him have in fact made an embarrassing mistake in the very first sentence. “They’ve got my birth date wrong. And if they can’t get my birth date right, which you can get on common knowledge, then everything else has got to be ignored,” Plimer comments. In fact, he was born in August of the same year.

However, raising the topic of ‘misinformation’ issue at the beginning of a Wikipedia article about a scientist is most probably deliberate – the editors probably think that the first thing the reader should know is that the person in question has a different, even dubious, view of generally accepted positions. This approach is not at all unique to Plimer or even to climate science. The same applies, for example, to the doctors and scientists who, during the Covid crisis, were critical of the panic-mongering, and lockdowns, recommended cheap drugs available to treat the disease like ivermectin, and questioned the efficacy and safety of vaccines (see e.g. here and here). Although Wikipedia still calls many of them spreaders of misinformation, it is clear, especially in retrospect, that their claims had a solid factual basis, while those claims that were continuously propagated did not.

As for Plimer, despite the possible attempt to cast doubt on his credibility, the claims that he rejects the scientific consensus on climate change and that he has been criticised by climate scientists, are factually accurate. Plimer backs this up with his characteristic humorous remark. “I thank Wikipedia for telling me that I’m a true scientist. I’ve never followed this consensus and the scientists have to use evidence. We don’t use what our peers say,” he says.

‘Global boiling is absolute nonsense’

But precisely this ‘scientific consensus’ is always being cited when the world’s most influential people talk to us about anthropogenic global warming and the catastrophe it represents. For example, at the end of July last year, UN Secretary-General António Guterres said that the era of global warming was over and the era of “global boiling” had arrived. “And for scientists, it is unequivocal – humans are to blame,” he said.

“I’ve been told many things in my life,” Plimer comments on this. “I’ve been told there was Father Christmas. I’ve been told, and this was a long long time ago, by young women that they love me. So you learn to be sceptical,” he says, again with his trademark humour, and reiterates that he’s always interested in the evidence. “To use terms like ‘global boiling’ is clearly absolute nonsense. This is a clear hyperbole to try to frighten us because by frightening us you then don’t have to present evidence,” Plimer points out.

Plimer has been criticising climate catastrophe predictions for decades. As a geologist, he says, he has been trained to observe and then analyse whether and how the observations relate to previous observations. Therefore, it is not possible for him to simply believe anything or anyone without evidence. Belief is also the wrong word when talking about science. “Belief is used in politics, it’s used in religion,” Plimer says. You can believe, for example, in the end of the world, which is also predicted for us because of climate change. “We’ve had thousands of years of people telling us the world is going to end. If just one of these predictions was correct, we wouldn’t be here,” Plimer points out.

Science and belief don’t mix. “Science is married to evidence and we come to conclusions based on evidence,” Plimer says, adding that as new evidence comes to light, conclusions have to change. He cites the example of how he has had the pleasure to correct his own scientific conclusions as some of the research he had published years ago has subsequently had to be refuted by new data and a better understanding of the research topic at hand. “I’ve criticised myself and I think that’s what science is about. It’s all about criticism,” he says. However, as soon as someone uses exaggerations about climate change, such as the oceans are boiling or so on, or talks about believing or not believing in climate change, it is not science, but propaganda, he explains.

What drives climate change?

But climate change, and even conditions that could be considered a climate crisis, are facts, Plimer says. He cites the example of the ‘Little Ice Age’, which began around 1300 and lasted until around mid-19th century, depending on the source of the estimate. This was a serious crisis. Long, cold winters meant reduced yields and famines. Malnourished people were in poorer health and, for example, Europeans’ growth also declined physically during this period. Scarcity led to more wars and few would disagree with Plimer who says that our lives today are incomparably better than they were then.

Canals and rivers in Great Britain and the Netherlands were frequently frozen deeply enough to support ice skating and winter festivals during the ‘Little Ice Age’. (Dutch painter Hendrick Avercamp, ‘A Scene on the Ice’ from the first half of the 17th Century.)

But if you look back thousands, hundreds of thousands, and millions of years, climate change has been happening on our planet all along. According to Plimer, the planet’s climate changes cyclically and is influenced by a variety of factors – tectonic changes, astronomical changes, cosmic radiation, orbital cycles, changes in the distance and activity of the sun, changes in ocean currents, etc. According to Plimer, we have known and measured these natural cycles for a long time, but the climate is also influenced by phenomena we do not understand so well. “A massive volcanic eruption can change climate and we’ve seen this a number of times in the past,” he says. At the same time, 70% of the Earth is covered by ocean, in fact, most volcanoes are underwater, and underwater volcanic activity directly affects the oceans by warming them and adding CO2. Plimer says we don’t know exactly how this affects the climate. “Climate is very complicated. It’s not based on a simple gas, carbon dioxide,” Plimer says, adding that the main greenhouse gas in the atmosphere is actually water vapour, and the clouds it creates directly affect our climate.

CO2 does not drive climate change

But as for CO2, which Western countries are working to reduce in an effort to supposedly prevent climate change, Plimer says that although it does have some warming effect as a greenhouse gas, it cannot change the climate. In fact, the more CO2 that is added to the atmosphere, the less each molecule that is added warms the atmosphere because the atmosphere gets saturated with it.

Plimer also points out that ice core studies have shown that every time the climate warms, the temperature rises first, and only then does the CO2 level in the atmosphere rise. The reason why more CO2 is getting released is because the ocean is warming – colder water withholds more CO2, and as the ocean warms more CO2 is released. “We’ve had six great ice ages in the history of our planet and six out of these six great ice ages started when there was more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere than now,” Plimer explains. Three of these ice ages were when we had 20% CO2 in the atmosphere. Today, that level is about 0.04%. It is important to note that 97% of the CO2 cycle is a natural process, and that anthropogenic CO2 emissions account for only 3%, according to Plimer. So to prove that anthropogenic CO2 causes global warming, it would also have to be shown that 97% of CO2 does not. “The whole argument is ridiculous from the start. It has never been shown that human emissions of carbon dioxide drive global warming. And why would we want to get rid of this carbon dioxide? It is plant food,” Plimer says.

“The only thing about renewable energy is that the subsidies are renewable”

But it is precisely this man-made CO2 that is at the heart of climate policies, and for this people will have to give up the reliable energy sources they have, replace them with less reliable ones, and be forced to limit their lives in other ways. “I don’t think it’s got anything to do with the environment. I don’t think it’s got anything to do with looking after your fellow man. I think it’s where unelected elites have seen a mechanism whereby they can make a huge amount of money and where they can control the average person, yet they don’t have to face an election,” he adds.

Part of this, Plimer says, has been the constant talk and scaremongering that fossil fuels are about to run out. “We’ve had that argument going on for 60 years now about peak oil. I don’t know about your country, but we have 3,000 years of coal in Australia, we have about 2,000 years of gas and we have more than 50 million years of uranium. It will take a very, very long time before we run out and by then we may be extinct or we may have different energy systems altogether,” he says. Only recently, oil reserves larger than 50 years’ worth of North Sea production were found off Antarctica, and this has already got the major world powers arguing about who should own them.

So according to Plimer, we won’t run out of fossil fuels just yet. “What we’ve run out of is common sense. And they’re trying to make us run out of money,” he says, referring to the ‘green transition’ and Net Zero, in other words replacing fossil fuels with renewable energy such as wind turbines and solar panels. “The only thing about renewable energy is that the subsidies are renewable. The subsidies just keep coming. If we had no subsidies, we would have no so-called renewable energy. And if we had wind and solar competing on a level playing field with nuclear, with coal, with gas, with hydro, then we probably wouldn’t see a wind turbine or solar facility anywhere in the world,” Plimer says.

The environmental damage of a ‘green turnaround’

Another important factor that cannot be overlooked is the real environmental impact, or real environmental damage, of wind turbines, solar panels, electric vehicles and other ‘green technologies’ that are said to save the climate. Plimer gives some examples. Solar panels are made using metals such as lead and cadmium, which are toxic and are very likely to end up in the soil and groundwater after a relatively short life cycle as a solar panel. Because they do not decay, they create persistent pollution.

He gives another one for wind turbines. A toxic chemical called ‘bisphenol’ is used in the construction of wind turbine blades. The use of bisphenol is banned in almost all Western countries, according to Plimer. For example, continuous exposure to this chemical increases the risk of cancer. Now, when the wind turbines reach the end of their life cycle – which again is not very long, about 15 years – the blades will be removed from the wind turbines and can not be reused or recycled. Instead, it is customary for them to be buried. From there the poison also ends up in the soil and groundwater.

In addition to the direct poisoning of groundwater and soil, wind farms and solar farms also have harmful effects on wildlife and animals. “If you love wind turbines, you are quite happy to slice and dice birds and bats. And if they’re offshore, to kill whales,” Plimer says, noting that protecting the environment has nothing to do with any of this.

Plimer cites the production of electric vehicles (EV) as another example. He points to the fact that it takes six times as much mining to produce an EV as it does to produce an internal combustion engine car. And there is a considerable shortage of the minerals needed, such as rare earths, cobalt, lithium, copper, etc. This means that we have to go deeper and deeper in mining. In the case of copper, for example, we could previously expect to find ore of 10% practically at the surface. Now, however, the ore is being mined deeper and the copper content in the ore has also dropped by a factor of 20 – to 0.5%. Plimer says this means that a lot more material is being excavated from the ground, which is then simply left aside – quite clearly, much more damage is being done to the ground than before. The factories where copper is extracted from the ore also have more material left over. “By increasing the amount of resources we use for the renewables we are actually creating a massive environmental problem,” Plimer says. It has financial impact as well – the price of copper has almost doubled on the world market in the last five years.

Dependence on authoritarian China

In addition, the materials we need for ‘green technologies’ are coming from third-world countries and we are simply turning a blind eye to the damage caused there. “If you are driving an electric vehicle and you are feeling morally superior to those monsters driving around a diesel or a gasoline vehicle, then you should know that for an electric vehicle, you use a lot of cobalt. That cobalt is mined by slave children in the Congo. And China controls the world’s cobalt industry,” Plimer says. He adds that China controls the global market for rare earths, which are needed to make wind turbines, solar panels and EVs as well. And the fact is that China now largely controls the production of all these things. So if you like all these things, you are directly supporting Communist China and the development of their economy, which in some places – for example, with regard to the Uighurs – uses forced labour.

Similarly, it should be borne in mind that China itself is not engaged in the same kind of CO2 emission reduction as the West, for in 2022, for example, the country was commissioning new coal plants at the rate of two per week.

China imports most of its coal from Indonesia and Plimer’s home country Australia. “We have about a dozen power stations and there’s huge pressure to close them down. China has 12,200 coal-fired power stations and is building two power stations a week. India is doing the same sort of growth,” Plimer says. “If coal was so bad, we wouldn’t export coal, which happens to be our biggest export at present. We would go broke trying to save the world,” he adds.

Plimer says that literally, the whole of the West’s economic growth has relied on coal and, later, other fossil fuels. This is linked to the development of industry, transport, medicine and other sectors that are vital to society. In addition, every day we use some 6,000 essential chemicals that we get from processing coal or oil. In addition, abandoning fossil fuels would also mean abandoning cheap and reliable energy production. Indeed, if we do this, we will create major problems for ourselves in terms of energy dependence, while at the same time making ourselves totally dependent on authoritarian China. In Plimer’s view, this is all just very stupid.

Geologist accused of relation to mineral exploration?

While Wikipedia tries hard to show that there are some climate scientists who think he has been spreading misinformation, there are of course others who try ad hominem arguments on him. One of them suggests that his positions on climate change are somehow influenced by his involvement with various mining companies. “Well, what a surprise! Geology involves doing mineral exploration and involves taking those minerals out of the ground. We wouldn’t have energy, we wouldn’t have metals, we wouldn’t have anything in today’s world without geology. This smartphone of mine – there are about 70 elements in the periodic table that are in that phone. If you want to have that criticism, then you should be giving me that criticism from the entrance to your cave. But if you live in the modern world, you are a beneficiary of geology,” he says. Yes, Plimer has connections with companies extracting coal, oil or natural gas, but alongside that, others associated with him mine iron, copper, gold, lead, silver and anything else you can find in the ground. Shouldn’t his association with, say, a copper-mining company make him a great lover of ‘green transition’ technologies and a preacher of the climate crisis?

First published by Freedom Research. Subscribe here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Hydrocarbons are renewable, replenished at the core and mantle. They are clean, efficient and necessary for a modern society. Co2 is a rounding error 95% emitted by Gaia, necessary for life. You want more not less of Co2. End. Of. Story.

As Plimer has been saying for decades, green tech is not green, it is inefficient, it destroys Gaia and is saturated with hydrocarbons in the production, distribution and operations of these ineffective platforms. The average bird chopper has 30K tonnes of steel, aluminium, plastic, cement and 700 gallons of lubricant oil to function. It will murder 500-1500 birds a year. What is ‘net zero carbon’ about that? Nothing of course.

It is a cult of control, the NWO, full of criminality, corruption, fraud and if you the sheeple believe in it, anti-science stupid.

The Wikipedia stranglehold on the Internet gets bigger every day. Virtually every search engine but Mojeek will show them first even when, amazingly, you sometimes search specifically for a website (eg EBay) and you get a Wikipedia article about them instead? Its clearly a method of worldwide information control. And once they are first in searches, even out of context, they are nearly impossible to dethrone because of the way Google AI rankings are setup. The best way to kill Wikipedia, very necessary and esp for our kids, is to NEVER click on them after a search because each Wiki click cements their Leftist censorship even further. As if you didn’t know, the main perpetrator is Google – and they are heavily invested in them in their worldwide info monopoly.

Equally, don’t fall for their “We’re broke! Please donate $$$ to protect this wonderful trove of information”

They have plenty of funds.

Coincidentally I just googled for “Cleveland vaccination study”. The top item dated from Feb 2023 was a “health warning”:

There were other “Fact checks” on the same first page, though most items were sales pitches for vaccination, and one was on how to counter “vaccine hesitancy”.

I’m becoming more interested in how search engine rankings are calculated (or paid for) on a topic than I am in the topic I am investigating!

If it is true that people seldom scroll past the first page, then getting one’s message on the front page, even at a high price, becomes the priority rather than truth.

I believe that their so called ranking formula is based on site references and popularity. Both of which are determined by the censors. So, expect Wikipedia at the top followed by your Govt and MSM sites. Everywhere in the world. And it seldom matters which Google “Alternative” you use as everything feeds off Google somehow. So far, I have has some success with Mojeek but your results may vary.

Professor Ian Plimer is one of those individuals in alarmingly short supply, it appears.

When he says that it is not possible for him to simply believe anything or anyone without evidence, he is simply stating what used to be (but seems to be no longer) the blindingly obvious.

But not, it seems, in government where in excess of £400bn can be spent without even so much as cost benefit analysis on the basis of zero (or confected, erroneous, exaggerated) evidence regarding the case fatality rate of a simple common cold coronavirus.

And the very same individuals (e.g. Vallance) responsible for that disastrous debacle are sounding off again regarding climate change, once again putting up no evidence whatsoever in support of their silly vapourings.

That is why everyone is so angry with this government and set to be even angrier about the next.

“Belief is used in politics, it’s used in religion,” Plimer says, and yet we are invited to pay ever higher taxes each year for a public sector bureaucracy whose job it is to advise, based on evidence: ‘On the one hand this, on the other hand….’

Whatever happened to the notion of flocking evidence?

We are comprehensively fecked.

Funny how it is only the wealthy western world and its Liberal Progressive Governments (including the Tories) that are to save the world from this “global boiling”, while the developing world are free to use as much coal as they want. Does the planet only boil with CO2 emissions coming from the UK, Europe and the United States, while not bothering to boil with all the Chinese and Indian emissions? ———-But notice you will never see an article like this or any of its contents on BBC, Sky News, Gaurdian, Independent or any other channel or publication pushing the Climate Change emergency story because they have all decided that “Climate change is real and happening now”. But what does that even mean? It means NOTHING. It is not a scientific statement. It is a political one, designed to force eco socialist politics down your throat as if there was only one world view that you can have, and you should never question this view. But ofcourse if something is really about science then you question everything.

World’s hottest land surface temperature – 56.7°C [July 1913 – Death Valley]

World’s hottest sea surface temperature – 38C [2023 – in shallows off Florida]

Usual Open ocean high temperature – 32C

Boiling Point of water – 100C

I have never ever seen a puddle of water boil under the sun, not even a shallow one. And I doubt whether anyone will see a boiling puddle in Death Valley or Libya , or anywhere.

Interesting downvote. Would you care to share your reasoning please?

C’mon guys ——8 comments only. We are letting the eco socialists off with murder. And I don’t just mean that metaphorically. Increasing energy costs and impoverishing people will cause death.

Even if CO2 does drive climate change, I’d like to see the evidence that the 3% mankind is apparently responsible for is far more significant than the other, natural, 97%…

One of the best articles on the subject I’ve ever seen. Well thought out, reasoned arguments and everything covered with facts. If this became mainstream it would be the end for the climate nutters.

They would, of course, move on to some other nonsensical argument; they’ve been doing this since 1972 when they said we would be in an Ice Age by 1984, they didn’t seem to realise they were at the tail end of an Ice Age. As it happens 1984 was extremely hot and I was working under a wooden roof all Summer.

Wikipedia – edited by 7 year olds and sad adults who spend their lives on it including reversing edits correcting their fake information.

Great read. Many new angles. I’ve got his book. I think it is called Green Murder. I thought reading Dr Patrick Moore’s book and so many good articles was enough. I need more time in my days.

I wish we would stop calling them ‘fossil fuels’; they’re hydrocarbons, and may well have little to do with so-called ‘organic fossils’.