As I make my way home from work, I occasionally catch a glimpse of the headlines on a fellow commuter’s newspaper. Recently there seem to have been a lot of scary headlines relating to whooping cough, such as ‘Pregnant women urged to get vaccinated amid surge in whooping cough cases’ and ‘More babies could die from whooping cough, says vaccination expert’. It seems that there has been a drop in vaccination rates in pregnant mothers and that babies who have been infected with whooping cough are predominately those of mothers who didn’t receive the vaccination during pregnancy. So, the inference was very much that unvaccinated mothers were to blame for this outbreak. However, in the light of my somewhat sceptical view of the Covid vaccine, I wondered if this was just another bit of propaganda trying to get pregnant women to take a vaccine they either didn’t want or didn’t need. But it turns out, it isn’t as simple as that.

Whooping cough can affect people of any age but mainly affects the younger population and it is particularly serious in infants. It is caused by a bacterium (Bordetella pertussis or Bordetella parapertussis) which can be found in the mouth, nose and throat of infected people. The infection often starts with typical cough and cold symptoms which develop into coughing bouts that can last several minutes. The cough, particularly in babies, may have a distinctive ‘whoop’ and babies can struggle to breathe due to the coughing. In the U.K. so far during 2024, five infants have died from whooping cough. Pregnant women are advised to get vaccinated against whooping cough during their pregnancy, even if they received the vaccination when they were babies themselves. This is so that they can pass on the benefits of the vaccination to their unborn babies who would be too young, when born, to receive the vaccination themselves or not have sufficient time to build up immunity to protect them against infection. Whooping cough vaccination is typically given at eight, 12 and 16 weeks but that leaves babies under three months old quite vulnerable to infection if their mothers didn’t get vaccinated during pregnancy.

But, you may ask (well as I asked actually), “Why is there an increase in the rate of whooping cough? I thought that vaccination had been pretty successful to keep the rates of infection fairly low. Is it just, as the headlines might lead you to believe, irresponsible pregnant mothers who are to blame?”

If we look into the history of whooping cough, we find that it really was quite a serious disease back in the 1940s. In the U.K., there were approximately 2,500 deaths in infants under one year of age each year from whooping cough. Following the introduction of the whooping cough vaccine around 1950, there was a dramatic decrease in infant whooping cough deaths, reducing to around 80 per year by the early 1970s with some increased mortality during outbreaks. The decline in infant deaths continued through the 1980s and into the early 2000s. By the year 2000, there were just two reported deaths in the U.K. from whooping cough. Even for the most sceptical anti-vaxxer, this looks like a success.

So, what changed and why are we now seeing an increase in cases and an increase in deaths in infants? As in many things, the devil is in the detail. Up until 2004, the U.K. used a whole-cell pertussis (wP) vaccine. However, in 2004, in the U.K., the vaccine was changed to the acellular pertussis (aP) vaccine due to concerns about the side-effects and safety profile of the wP vaccine. Most of the side-effects were non-serious such as fever, redness, swelling at the injection site and persistent crying, but there were concerns about more serious side-effects such as febrile seizures and encephalopathy. The side effect profile of the aP vaccine was better with lower incidence of fever, local reactions and other side-effects. Although the main safety concerns for the wP vaccine related to seizures and encephalopathy, large epidemiological studies found no causal link between the wP vaccine and permanent neurological damage. At this time, the whooping cough vaccine was not usually given to pregnant women although, for both the wP and aP vaccine, the safety profile in pregnancy appears good.

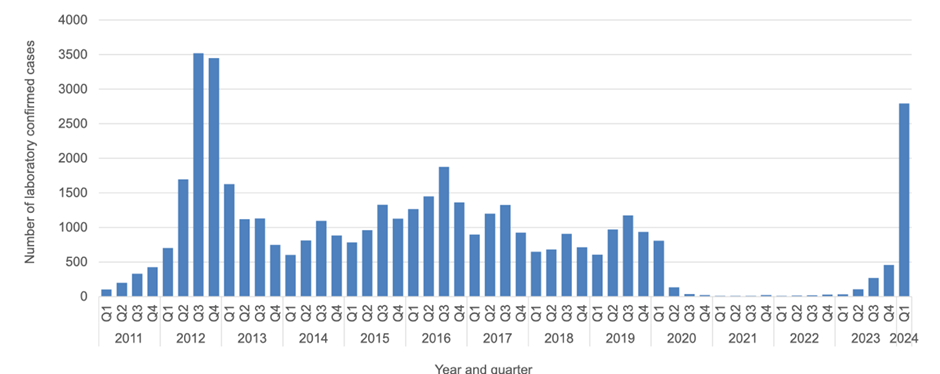

Whooping cough was kept pretty much under control following the change from the wP to the aP vaccine. The case numbers in England were 336 in 2002, 192 in 2003 and 256 in 2004. They gradually began to rise in the subsequent years with 366 cases in 2005, 404 in 2006 and 615 in 2007. However, laboratory confirmed cases continued to rise gradually until 2011/12 when there was another outbreak of whooping cough (Fig 1) with 1,053 cases in 2011 and 9,367 cases in 2012.

This outbreak in 2012 led to a change in health policy and the introduction of the vaccination of pregnant women. However, in spite of that change in policy, cases didn’t return to pre-2004 levels. The only time we see case numbers drop is during the Covid pandemic. Some argue that this relates to social distancing reducing the infection rate of whooping cough, but it seems just as likely that whooping cough cases were assigned as Covid cases due to the similarity of symptoms.

I wondered whether infection rates were similar in other countries and what I found out was rather interesting. Some countries, such as the USA, Australia and several European countries all introduced the aP vaccine somewhere between the late 1990s and early 2000s. The USA has experienced increased cases of whooping cough since the switch to the aP vaccine with significant outbreaks occurring in recent years. A similar story can be found in Australia and the European countries that switched to the aP vaccine. However, in those countries which continued to use the wP vaccine, there is a different story. In countries such as Brazil, India and China where the wP vaccine continues to be used, the infection rates remain stable. Studies comparing populations vaccinated with the wP vaccine versus those vaccinated with the aP vaccine have consistently shown higher rates of whooping cough in the latter group as immunity wears off more quickly. Data also indicates that individuals who received the wP vaccine have more robust long-term immunity compared to those who received the aP vaccine.

I wondered if, on balance, there were likely to be more deaths and serious adverse events from using one or other vaccine taking into account both the side-effects of the vaccine and the deaths from the disease itself. These data are more difficult to tease out, but it seems that, although minor side-effects such as fever, redness and swelling at the injection site occur more often with the wP vaccine than with the aP vaccine, deaths from the wP vaccine are rare (mainly related to allergic reactions). However, it must be understood that the whooping cough vaccine was and still is given as a combination vaccine with vaccines against other diseases such as diphtheria and tetanus, so you can’t necessarily blame the wP vaccine alone for such deaths. It is very difficult to get reliable figures as adverse events and deaths from vaccines are poorly reported and a more in-depth study would be required to look into this in more detail comparing vaccination deaths either pre- and post-introduction of the aP vaccine or comparing deaths in countries using different vaccines. But even then reporting rates at different times and in different countries may bias results. What is clear is that there is definitely a trade-off between reduced vaccine-related morbidity and increased whooping cough-related morbidity and mortality and it may be more prudent to, instead of blaming unvaccinated pregnant mothers for the recent outbreak, to switch back to the more effective wP vaccine before we start to return to pre-1950 levels of whooping cough in the U.K.

Dr. Maggie Cooper is a pharmacist and research scientist.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

“Covid Inquiry Invites Input From 17 Members of Pro-Lockdown Left-wing Lobby Group ‘Independent SAGE’ Led by Communist Susan Michie”

Sounds fair!

Par for the course..

Protecting themselves, and not real people, perhaps. Anyway, as there was an “independent SAGE”. Perhaps there should be an independent inquiry – indeed, there is one. You don’t have to look too far for that, if it’s organised and ready to dispute the results of the other lot.

Next they will canvass Hancock, Doris, Ferguson, Whitty, Starmer, Sturgeon, Drakeford et al, who will say that they did not do enough, hard enough, fast enough, or deep enough. But there is always next time. Learn from our mistakes, upon reflection, insights etc etc.

“Baroness Heather Hallett, the Chair of the Inquiry, has written to 17 members of Independent Sage which criticised the country’s re-opening and later called for fresh lockdowns.”

in that case, why not just lock her down? She’ll be happy then and can have a whale of a time in solitary confinement!

What a splendid idea.. why didn’t I think of that.. ???

Answer : obviously not as bright as Dinger.. 😉

Well.. Michie’s one red I wouldn’t want under my bed.. and certainly not in it.. perish the thought..

🤣🤣 seriously mate you dont have to be bright to keep up with me, I’m no great shakes! But thankyou anyway 👍

“Independent SAGE” may have been “Independent” of the government, but they are “dependent” on the “pandemic” industry for their existence and importance. Ditto WHO, Big Pharma, “real” SAGE. Goodness knows why so many people took all their pronouncements at face value rather than as people “talking their book”.

MULTI-MILLIONAIRE communist Susan Michie.

Sounds like she’s a little more “equal” than the rest of her comrades!

It’s funny how Communism, whilst claiming to liberate the prolitariate, always seems to have some very rich backers. Could it be that it’s nothing more that a scam to monopolise markets and inflict one’s own hubristic fantasies about the world should be on everyone else?

Susan Michie is probably far right according Marianna Spring.

Everybody is far right according to that lefty tart!

As if the Covid inquiry was anything other than a gaslighting pantomime to mask the greatest looting spree and assault on our lives in modern history.

You know the government is just screwing with us by pretending they are concerned what happened during lockdown , they don’t give a damn.

The COVID inquiry is a political farce supposed to find out that evil Tories killed loads of people by not doing everything-corona earlier, harder, faster and for longer because they cared more about insignificant things like the economy and just don’t care about important things like people. When the select independent SAGE for input but omit HART (for instance) it’s absolutely clear who’s driving the car and where the journey’s supposed to go.

I read of these trips , one journey ended near Durham (or north of Islington) at a beer and curry party that was sanctioned by the police during lockdown.

Right. Instead of asking whether lockdown worked, they are assuming it did. Some inquiry!

Specifically, the Mitch-Thing wanted to keep mandatory public face masking forever as that was never really about COVID. She admitted as such in an interview in 2021, at the height of her pandemic career. She had seen many people with such masks during an earlier holiday in Japan and badly wanted to get Britons to wear them as well to combat unspecific dangerous germs.

“Germs”, such a scientific term

“Independent SAGE”

…

“The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea”

…

“German Democratic Republic”

You know when they have to say it, it’s because they aren’t.

‘Independent SAGE’, aka ‘Communist SAGE’!

Anyone expecting a proper Inquiry – listening to both sides of the debate – hasn’t been paying attention for the past 3 years.

If you didn’t agree/conform to the Government “line to take” you were silenced. And the Inquiry will do the same, since there must be only one outcome: “lockdowns were justified; the destruction was necessary; the Government did what the Government had to do.”

Move along ….. nothing to see or discuss.

But “lessons will be learned” so that’s OK then

“Take a lateral flow test before entering the building” WTF?

Nowhere does it say HOW LONG befiore – I’m sure that 2 years will suffice.

Governments are whitewashing all the unnecessary damages, destruction of livelihoods, injuries and deaths they caused with their covid policies. You can bet that any government initiated inquiry will do the same as was done during covid. In Canada a National Citizens Inquiry (NCI) was formed to record and has been holding townhall meetings across country inviting people to give testimony. You can find them at https://nationalcitizensinquiry.ca . Many Doctors have testified how they were threatened and coerced and also how they were prevented from giving treatment and reporting vaccine injuries.

“Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.”

Sorry I really don’t care anymore and if it gets me banned it will be worth it and I’ll cancel my subscription to this site so f it!

ARSEHOLES!!! The lot of them.