Citations are the currency of academia. Scholars who manage to gain a lot of them are more likely to get promoted, more likely to win prestigious awards and more likely to win the respect of their peers. An academic with a lot of citations is kind of like a City banker with a large end-of-year bonus – a big deal.

Given the importance attached to citation counts, scholars have an incentive to boost theirs by any means necessary. One practice that has received significant attention is self-citations. This is where individuals make a disproportionate number of citations to their own work. Another, related phenomenon is citation cartels. These refer to groups of individuals who agree to make a disproportionate number of citations to each other’s work.

Individuals who boost their citation counts through underhand practices obviously gain an unfair advantage over those who play by the rules. Hence there is considerable interest in detecting such practices, which are collectively termed ‘citation manipulation’.

In an interesting new paper, Hazem Ibrahim and colleagues investigate citation manipulation by analysing a dataset of 1.6 million Google scholar profiles. They find evidence that some individuals are indeed gaming the system. And they outline a method for identifying potentially suspicious individuals.

To look for evidence of citation manipulation, the authors began by filtering the dataset for individuals who saw large spikes in their citation counts in a particular year. They then zoomed-in further by identifying five individuals who received a large percentage of their citations from just a few papers that each cited them many times. These five individuals were deemed ‘suspicious’.

To check for evidence of citation manipulation, Ibrahim and colleagues compared the suspicious individuals to individuals who were similar in terms of field of research, year of first publication and total number of citations.

They began by computing the number of citations individuals in each group received in their peak citation year on Google Scholar and on Scopus (the latter only indexes journals that have been approved by an advisory board). They found that the matched individuals’ citation counts were only 45% lower on Scopus, whereas the suspicious individuals’ counts were 96% lower. This means that in the years when suspicious individuals saw large spikes in their citation counts, most of these citations came from journals not indexed by Scopus.

The authors proceeded to compute the number of citations individuals in each group received in the ten papers in which they were cited most. They found that the matched individuals were cited no more than 15 times in such papers, whereas the suspicious individuals were cited up to 45 times. This means that suspicious individuals received an excessive number of citations from a small number of papers.

Ibrahim and colleagues then propose a method for identifying potentially suspicious individuals, which involves computing two quantities for a certain individual.

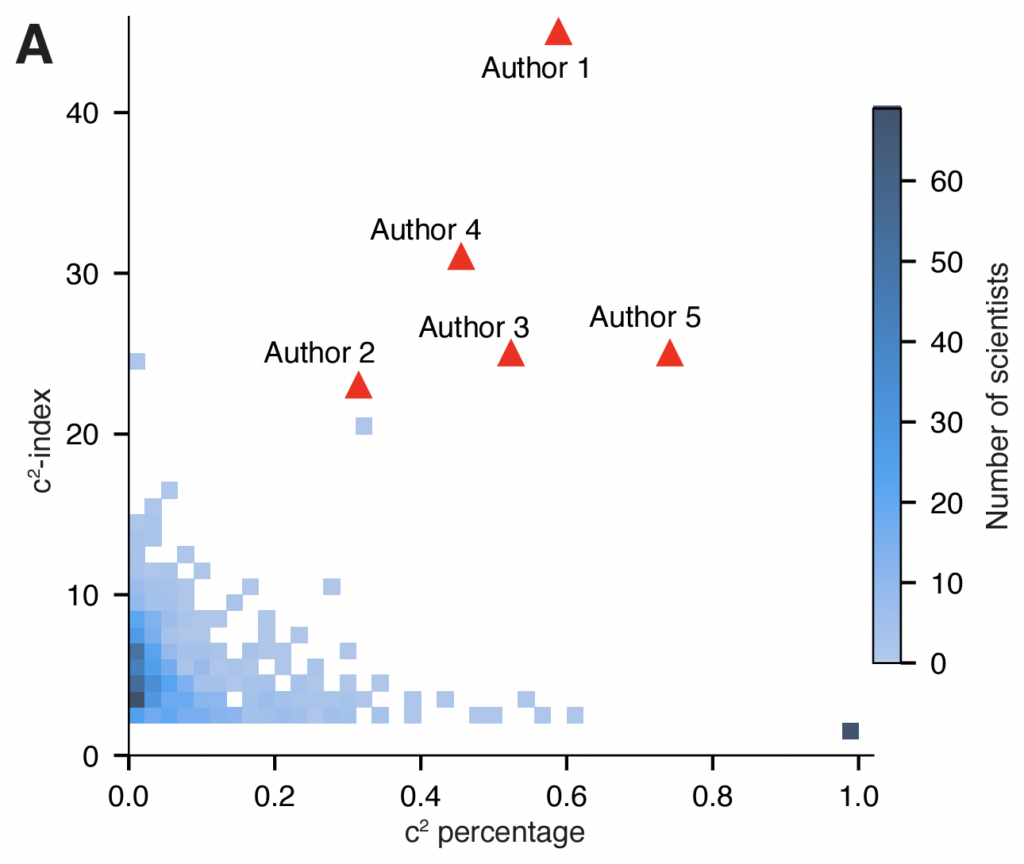

The first is the ‘citation concentration’ or c2-index, defined as the largest number n such that there are n papers that each cite the individual at least n times. For example, if there are 10 papers that each cite the individual at least 10 times, they would have a c2 index of 10. The second quantity is the c2 percentage, defined as the percentage of the individual’s total citations that are accounted for by the n papers. For example, if 50% of the individual’s total citations are from the 10 papers, they would have a c2 percentage of 50.

The chart below shows the distribution of 900 individuals across dimensions corresponding to the two preceding quantities. The five suspicious individuals are highlighted in red. As you can see, most individuals are concentrated in the lower left-hand corner. By contrast, the five suspicious individuals are all located in the upper right-hand area. This discrepancy makes it very unlikely that all their citations are genuine.

In the final part of their paper, the authors demonstrate that it is possible to boost one’s citation count on Google Scholar by creating AI-generated papers that include larger numbers of citations to one’s work and then posting those papers on preprint servers. They also demonstrate that it is possible to pay to have one’s citation count boosted: for a fee, fake journals will publish papers that include large numbers of citations to your work.

In terms of corrective actions, Ibrahim and colleagues call for bibliographic databases like Google Scholar to publish the c2-index alongside traditional citation metrics. Unfortunately, this is likely to be little more than a patch. If the c2-index does become widely published, bad actors could get around it by using AI to generate many papers that each cite the relevant individual a small number of times.

In an era of cheap and widely available artificial intelligence, stopping citation manipulation will be an uphill battle.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

How many climate ‘science’ papers and authors would this highlight?

Deleted – link didn’t work.

Its here: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2402.04607.pdf

Chart in the text above is on page 11.

But at the end of the day, unscrupulous scholars with an ideology to push are going to use every means possible to grandstand their ideas no matter now unethical, aren’t they?