Let’s begin this post with a quick question that has proved surprisingly difficult for human rights lawyers and judges to answer: is it better to have more murderous sociopaths in your country, or fewer?

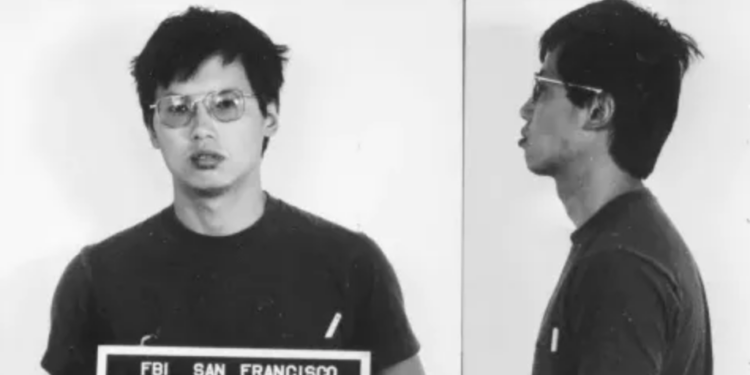

This question came to a head in the strange and squalid case of Charles Ng, not the first person one would associate with the development of international human rights jurisprudence. Together with his accomplice Leonard Lake, Ng kidnapped, raped, tortured and murdered somewhere between 11 and 25 people – including infant children – in California in the early-mid 1980s. There is little doubt about the guilt of the two men: they recorded themselves doing much of it on video camera. They were caught by their own sheer mendacity in 1985; at a shop they visited Ng (a kleptomaniac along with his many other character flaws) was unable to resist shoplifting an item, and the police were soon summoned. Lake was arrested and shortly afterwards took cyanide and died. Ng fled to Canada, where he again gave in to the urge to engage in petty crime and was arrested for shooting a security guard while stealing a can of salmon from a department store.

This sordid affair is important for our purposes because of what happened next. Ng was duly sent to prison in Alberta for shoplifting, assault with a weapon, and other offences. But in the meantime the investigating authorities south of the border had discovered the crimes that he and Lake had committed. Learning that Ng was currently residing in a jail cell up north, they sent a request to the Alberta authorities for his extradition to stand trial for what ultimately turned out to be 12 counts of homicide (he was ultimately convicted for 11).

Ng’s legal team here came up with ingenious argument as to why the request should be refused. Canada, you see, had abolished the death penalty for anything but some military offences in 1976. California had not (and actually still has not, although there is currently a moratorium on its use; nobody has been executed in California since 2006). Therefore, the argument ran, if Ng was extradited to California, that would be tantamount to Canada sending him to be executed by the backdoor. And this would violate the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, recently enacted in 1982, section 7 of which enshrined the right to life, and section 12 of which enshrined the right not to be subject to cruel and unusual punishment.

If Ng were to be executed in California, in other words, he would be deprived of his right to life and his right not to be subject to cruel and unusual punishment (partly because ‘death row phenomenon’ is purportedly in itself cruel), and therefore Canada would be violating its Charter of Rights and Freedoms by proxy. It would be sending Ng to face a violation of rights that were his by virtue of his being within the jurisdiction of Canada and thus under the application of the Charter. Therefore, the extradition should go ahead only if the Canadian Minister of Justice sought and obtained a guarantee from the State of California that Ng would not be executed.

The good news for Canadians is that the Supreme Court of Canada had an ounce or two of sense in those days, and knew perfectly well that, the rights and wrongs of the death penalty aside, deterrence in these matters is important. The absolute last thing that Canada needs, sharing a very long and very porous border with the USA, is the message being sent out that if one is resident in the USA and wishes for some reason – because one has just engaged in a bout of psychotic ultra-violence, perhaps – to avoid the application of the death penalty, all one need do is run away to Canada. The Supreme Court duly applied that common sense in its decision in Reference Re: Ng Extradition [1991] SCR 858 (conjoined with its judgment in Kindler v Canada (Minister of Justice) [1991] 2 SCR 779, involving a murderer and kidnapper who had similarly fled north, this time from Pennsylvania, to escape the death penalty). As the majority put it in their judgment in Kindler:

The Government has a right and duty to keep criminals out of Canada and to expel them by deportation. Otherwise Canada could become a haven for criminals.

There is nothing puzzling about that logic. Should a country want more, or fewer, criminals? Well, if the answer is the latter, then it should want to deter foreign criminals from coming. There should, it follows, be absolutely no incentive in public policy to encourage them to do so. If Ng and Kindler had been extradited only subject to the assurance that they would not be executed, this would, all else being equal, provide quite a good reason for criminal desperados fleeing the law in the U.S. to go north. And therefore such an assurance should not be sought. The Canadian Minister of Justice, whose responsibility it was to make these decisions, was therefore acting entirely properly and reasonably – and there was no basis for the Supreme Court finding his decision to be unlawful.

Ng was duly extradited (I believe this took place within half an hour of the Supreme Court’s judgment being handed down) and remains, at the time of writing, on death row in California. And there the matter should probably have ended; I am against the death penalty, but if ever there was an argument for its use, Charles Ng is a pretty good one. Malevolent psychopaths, though, have a tendency to create a nuisance of themselves even after capture, and Ng (obviously aided by legal campaigners) sent a subsequent complaint against Canada to the United Nations Human Rights Committee (HRC), arguing that his extradition, carried out without the assurance that he would not face the death penalty, had breached certain provisions of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), one of the main international human rights treaties.

The HRC is not able to give binding judgments on such matters, which is why they are referred to as “complaints” and why its procedures are generally called ‘quasi-judicial’. Put bluntly, its decisions are ‘authoritative’ but can be ignored. Nonetheless, the HRC took the opportunity in Ng v Canada (1994) to make a statement about this kind of situation. Brushing aside the arguments put forward by the Canadian Government with respect to deterrence, the judges took the view that while the extradition had not violated Ng’s rights under Article 6 of the ICCPR (the right to life), it had violated his rights under Article 7 (the right not to be subject to cruel or inhuman treatment). This was because the method of execution being used in California at that time, gas asphyxation, was by definition cruel, and Canada was therefore exposing Ng to cruel or inhuman treatment by proxy:

In the instant case and on the basis of the information before it, the Committee concludes that execution by gas asphyxiation, should the death penalty be imposed on [Ng], would not meet the test of “least possible physical and mental suffering”, and constitutes cruel and inhuman treatment, in violation of article 7 of the Covenant. Accordingly, Canada, which could reasonably foresee that Mr. Ng, if sentenced to death, would be executed in a way that amounts to a violation of article 7, failed to comply with its obligations under the Covenant, by extraditing Mr. Ng without having sought and received assurances that he would not be executed.

The point was moot by that time, of course, because Ng was already safely on death row – and, in a greater sense, all of the litigation I am here discussing was moot in that there is no likelihood Ng will ever actually face execution given the political climate in California. But the HRC’s decision in Ng v Canada nonetheless stood to be confirmed and expanded some years later in the case of Judge v Canada (2003). Judge – you’ll recognise the pattern – was convicted in Pennsylvania of two counts of first-degree murder (one of the victims was a 15 year old girl, an innocent bystander to a premeditated assassination) and sentenced to death. He then escaped and fled to British Columbia, in Canada, where he committed armed robbery and was duly convicted and jailed. Unlike Kindler and Ng, though, he was not extradited, but after serving his 10-year sentence was simply deported back to the U.S., straight into the hands of the authorities.

Again, the same kind of arguments were made by his legal team, and again the ultimate result was a complaint to the UN HRC. But this time the HRC went a step further than it had in Ng. It held that the mere deportation of somebody in Judge’s circumstances, whatever the manner of execution, would be a violation of his rights under Article 6 of the ICCPR – it would per se constitute a violation of his right to life. Canada had abolished the death penalty, and as an ‘abolitionist’ state it could not deport or extradite anybody to face the death penalty, at all, end of story. It had, therefore, violated Judge’s right to life in deporting him, QED. (It would presumably follow that Mr. Judge ought in the HRC’s view to have been allowed to remain in Canada after having served his sentence for armed robbery if the Canadian Government had not been able to receive assurances from the Pennsylvania authorities that he would not be executed.)

That was in 2003; the HRC was ahead of its time. It has become increasingly common across the developed world for judges, human rights lawyers and indeed most legal academics to display an exaggerated squeamishness about issues surrounding deportation and extradition of criminals. It is nowadays an almost weekly occurrence in the U.K., for example, to see cases such as that of Gjelosh Kolicaj or Arsimi Murati flit across the public awareness, wherein people who have committed serious criminal offences are somehow permitted to escape deportation due to procedural technicalities or because it has been held that their leaving the country would somehow violate their rights. Usually the right in question is Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which guarantees the right to a family life, on the basis that deportation of the defendant or appellant would make contact with close family members resident in the U.K. more difficult. But it can also be Article 3, which prohibits torture, on similar reasoning to that on display before the HRC in Ng. For example, to cite a case almost at random, in Secretary of State for the Home Department v ES (2023) an Albanian drug dealer escaped deportation because the Immigration Tribunal held that it would expose him to the risk of ill-treatment at the hands of the criminal gang who had helped traffic him into the U.K. illegally in the first place and to whom he still owed money.

One should not be dismissive of the complexities involved in these matters, of course. The European Convention on Human Rights and the Refugee Convention, as well as the ICCPR, enshrine either implicitly or explicitly the principle of non-refoulement (see a previous post of mine for more detail on this), which is founded in basic decency: as a general rule nobody should be expelled from a country if it is obvious that this would result in a serious violation of his or her rights. The principle exists for a good reason, which was that mass deportation of Jewish refugees from around Europe into the Third Reich had been an important mechanism in facilitating the Holocaust. The drafters of the international treaties in question obviously, and naturally, had this episode in the forefront of their minds. And it remains the case that there are many genuine asylum seekers in the world who are fleeing grave dangers and any civilised society should be proud that it is in a position to offer them sanctuary – this goes without saying.

But there are clearly circumstances in which, particularly when it comes to criminals, a blind and unthinking adherence to the sanctity of non-refoulement can become almost perverse. The now-iconic example in the U.K. is the case of Abdul Ezedi, a man from Afghanistan who was granted asylum despite having committed various serious sexual offences on the grounds that he had (spuriously) converted to Christianity and would face punishment as an apostate if he was deported back to his homeland. He repaid that kindness by shortly afterwards carrying out a brutal attack with a corrosive substance on a young mother and two small children. But his story seems to be repeated at scale across the developed world, with the presence of people who have proved themselves to be extremely dangerous being tolerated simply because it would, essentially, be unkind not to. (One might in this connection also recall the case of Muhammed Qassem Sawalha, a Hamas high-up who is not only permitted to reside in the U.K. and possess a U.K. passport, but has been generously subsidised by the taxpayer to make his home here.) The result is that our countries increasingly send out precisely the message that the Canadian Minister of Justice, back in the early 1990s, wished to avoid transmitting: if you can somehow make your way physically to the right destination, by hook or by crook, then no matter what you do, and no matter what you have done, so long as you have a vaguely plausible story about risks associated with deportation you will be safe from being returned to your country of origin. And after you have served your sentence you will therefore be free to remain.

One has to be very learned in the law indeed not to notice that there is something odd about all of this. It is almost as though the mere fact that somebody might face negative consequences from being expelled from a country ought in itself to trump any other consideration of public policy; that, indeed, the population of a country ought to put up with the presence of extremely dangerous intruders simply on the basis that that to reject that presence would be cruel to the intruders in question. This does not, on its face, seem very sensible. But it is the position at which we have arrived.

Of course, this mindset often manifests itself in complicated – sometimes sophistic – legal argument. But it is not, in the end, it seems to me, rooted in legal so much as emotional reasoning. There is a simple lack of willingness on display in much of the jurisprudence on these matters to take decisions that might have negative consequences for the persons subject to them. And this tends to be combined in public debate on the subject with a well-meaning but ultimately misguided desire to immediately squash any discussion of ‘immigration’ and ‘crime’ on the basis that it might ‘incite hatred’ or harm community relations. (The most obvious example of this that leaps to mind is the comments made by Kitty Holland, a journalist for the Irish Times, who advocated censorship of the victim impact statement of the fiancé of an Irish primary school teacher murdered by a Slovak national on the basis that it might provide ammunition for the “far Right”.) The application of the law then tends to follow from that initial position of reluctance, usually being couched in a ‘proportionality’ analysis which is, somewhat facetiously, presented as a matter of objectively weighing up the competing interests between the defendant and the public and finding in favour of the former.

This all has the unusual effect of casting the state in the role of a mother hen, fussily and aggressively interested in protecting its brood at all costs, with its brood defined simply on the basis of whoever happens to be within the borders at any given moment. All one needs to do is pass through the border, whereupon one is immediately brought within the warm, comforting, downy embrace of the maternal state and thereby insulated from harm, or indeed the ordinary consequences of one’s actions – even if one is a murderer, terrorist, sex offender and so on.

And this in turn has the effect of completely clouding judgement. Immigrants are ordinary people. This means that most of them are perfectly nice, decent and law-abiding. As it happens, my own daughters happened to befriend some kids at the local park, as children tend to do, the day before I wrote this post; they happened to be Syrian refugees. They were well-brought up, polite and shared their sweets. I was thus reminded yet again, if I needed reminding, that most people, most of the time, rub along together very well whatever their backgrounds are. But since immigrants are ordinary people, and since a small but not insignificant percentage of ordinary people are violent and dangerous, then we should hardly expect there to be no criminal element whatsoever amongst immigrant populations. Since almost 1.2 million people came to live in the U.K. in the year ending June 2023, this means that a sizeable number of criminals did too. It is utter foolishness to deny, then, that increased immigration means increased crime in nominal terms – not because immigrants are necessarily more likely to be criminals, but because more people inescapably means more criminals, all else being equal.

It is perfectly good and sensible public policy, then, to seek to limit this effect of mass migration (the rights and wrongs of that broader issue aside). And it is therefore perfectly good and sensible public policy to deport foreign-born people who have committed serious criminal offences, and to deter criminals overseas from imagining that one’s country is a ‘safe haven’ by making it clear to them that they will not be able to remain if they come. But the way in which human rights law has developed has resulted in almost the opposite scenario emerging, in which the message is sent out that, all things considered, a criminal lifestyle conducted in a developed Western state is much more fruitful and much less risky than it is elsewhere, and that even if one ends up being caught and convicted, one may very well end up being permitted to stay in the country indefinitely. In an era of mass migration, this is simply not good government.

The strange irony or paradox of the mother hen state, then, is that while it manifests itself in an almost absurdly strong desire to extend a forcefield of compassionate protection over everybody who comes into the jurisdiction, whatever they have done or might in future do, this has the effect of exposing the people who are already here to additional and unnecessary risk of harm. It is almost as though, in the modern developed state, the priorities of the putative Gjelosh Kolicajs and Abdul Ezedis of the world actually trump those of the resident population. What explains this?

There is no doubt that it partly stems from the fact that human rights lawyers, tribunal judges, employees of NGOs and activists tend to be of high social status, or aspire to be so, and that a contempt for the anxieties of those who are of low social status will always be de rigueur in such circles. Since it is overwhelmingly the poor (of whatever race or background) who face the consequences of increased crime, a certain blithe indifference to the matter on the part of those who purport to be society’s elite is, sadly, quite natural. But there is I think something else going on.

In The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Milan Kundera provides us with some clues, reminding us as he does that a great deal of what we think of as politics actually boils down to aesthetics. We easily form, with those who are liked-minded, idealised visions of what society should look like, and we are seduced by common feeling into believing that these dreams can actually be realised. It then becomes very difficult, when we have fallen in love with such beautiful shared flights of fancy, to accept that the real world is not and cannot be made perfect. And the fundamental imperfectibility of reality thereby becomes a source of great metaphysical anxiety. We thus always seek to ignore, deny, refute and squeeze out any fact, event or opinion which might force us to accept the imperfectibility of existence, in order that we can keep our wonderful visions of perfection unsullied.

This, Kundera tells us, has the same root as artistic kitsch. Kitsch, he says, is art which aims to salve our metaphysical anxiety by pretending, metaphorically, as though ‘shit’ does not exist – by, indeed, presenting to us a world that is purposively and studiedly perfect. The existence of shit is the great slap in the face to anybody who thinks that the world can be perfected, because as long as there are human beings they will have to shit, and the perfection of temporal existence will thus never be achievable. Kitsch is the aesthetic ideal in which this is not so – and kitschy art is that “in which shit is denied and everyone acts as though it did not exist”. It is art which expunges anything that is undesirable, discordant, awkward or imperfect, in the interests of displaying a kind of idealised niceness.

Political kitsch, then, has the same basic character: a vision in which, in the pursuit of perfection, the existence of shit is denied or ignored. And you can perhaps now see where this logic leads. The modern progressive liberal is defined above all else by being enamoured with an aesthetic ideal of perfection: a world in which all can, eventually, be made exactly equal; in which borders can be made not to exist; in which everybody can be ultimately liberated from the bonds of nation, religion, family, sex and so on; and in which – this is I think more significant than any other factor – everybody can be made nice in the sense that they will be the type of tolerant, well-behaved, kind, thoughtful, empathetic and almost childishly good-natured stereotype which progressive liberals unfailingly imagine themselves to represent.

To somebody who holds that aesthetic dear, and to whom its final achievability is a necessary political truth, it is incredibly difficult to accept that there are in fact people in the world who are not nice (or who cannot be made to be nice); that there are trade-offs to be made between the interests of some groups in a society against others; that tough decisions have to be made sometimes to preserve stability; that borders, biology, the laws of economics and so on are real – and that it can never be the case that literally everything can be tolerated.

The world, in other words, inescapably contains shit, and will always contain shit, in the sense that perfection is impossible. But to those imbued with a political kitsch shit’s existence must be denied. The fact that there will inevitably be some immigrants to a society who commit crime, and the fact that mass migration and open borders are not unalloyed goods, is simply too awkward to be tolerated, and these obvious truths must therefore be suppressed, both within the mind of the adherent, and in public discussion of the subject. The progressive liberal vision is one in which shit must be simply hidden – and, as a result, it is one in which public policy must pay no heed to the idea that deterrence of criminality across borders is even possible, let alone desirable.

The result is the strange circumstance we see before us, in which the only concern that is really permitted to be expressed about the prospect of crime committed by immigrants is that even to observe and comment upon its existence might ‘incite hatred’, and in which the perfectly sensible desire of ordinary people (including, ironically, the vast majority of immigrants) to inhabit a more safe and stable social environment than a less safe and stable one is given such little credence in polite society.

Dr. David McGrogan is an Associate Professor of Law at Northumbria Law School. You can subscribe to his Substack – News From Uncibal – here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Multi culturism and diversity is our strength.

Don’t look back in Anger.

Lessons will be learned.

Exactly.

It was Trump’s fault.

The Muslim Jihadist was forced to react to AfD’s rise to electoral prominence.

The white girl he raped was not young enough.

Times are tough.

Let’s not jump to conclusions!

Clearly it’s the AfD’s fault.

Some poor innocent refugee experienced so much institutional racism and hostility from the extreme right, he just couldn’t take any more and expressed his grievances in the form of a largely peaceful demonstration.

We won’t be divided. Willkommenskultur. Wir schaffen das.

yes, time to ban the AfD. It’s the only reasonable response.

Or is it, we’ve shafted you?

“A black car drove at high speed into people…”

These driverless cars are a menace.

Unless of course: A black car was driven at high speed into people.

Exactly what I was going to say, they said the same tosh when “an Suv drove into a marching band” in America, they make you sick with all this automatic immigrant apologising

Presumably the German government blames car dealers – in the same way that our scum-government blames Amazon for knife crime.

Well they *are* doing their best to destroy their own auto industry.

Your kitchen plus garden shed contains all the deadly weapons you could ever need as an aspiring criminal!

Even “was driven” is too watered down and passive. It should read “A man (whether or not identified) drove a car at high speed into people. Otherwise it looks like it’s the car’s fault!

Stand by for, “Not believed to be terrorism-related…”

…Until a few days later, “Linked to known terrorist organisations.”

How many more of these tragedies will it take before state-sponsored pandering to D.I.E. comes to its senses?

And don’t forget not to speculate!

Oh and mental illness!

And a one off random attack!, How many more one off random attacks has there been now?

And “on the watch list”.

And “Police are still searching for a motive”.

And “No photos or names of the perpetrators are available”.

And “Anyone spreading misinformation about this attack will be jailed.”

The Germans know what they have to do to stop this nightmare. Will they do what’s necessary?

They had their chance at the recent election and they blew it. As did we. The destruction of our countries seems to be just gradual enough that too many are still complacent/deluded.

You’re absolutely right.

No. In the recent elections 80% voted for the status-quo Parties, so the AfD with second highest vote won’t be involved in the next (eternal- coalition Government.

They must like it.

They either like it or feel it’s a justified punishment for some event in the past that no one now living bears any responsibility for. Since no amount of punishment can atone for a crime the modern Germans didn’t commit, unless the Germans wake up and get rid of their ruler-scum, their ruler-scum will destroy them.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1986_East_German_general_election

West German methods to coax voters into voting as they’re supposed to vote are more subtle (if one wants to call all public and private MSM shouting “AfD Nazis!” 24×7 subtle) but nevertheless equally effective.

The real news about this election is that the AfD doubled its share of the vote (from 10% to 20%).

They can start by arresting ex-Communist East German Youth Stasi Member Angela Kasner Merkel and charge her with CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY.

i’m not saying there isn’t too much immigration. I’m not saying there aren’t crazies out there.

But I can’t avoid a nagging feeling that these incidents in Germany aren’t just randos losing their heads with hatred going on copycat killing sprees.

I have no evidence to support this assertion but I would wager (not a huge amount mind you) that this is somehow instigated/coordinated.

And I have no evidence and even less to say about by whom.

Nah. It’s lone-wolves innit.

Well of course these Vehicular Jihad attacks are instigated, coordinated, trained, funded by the Global Caliphate mob! The Southport Stabber was known to have attended the Southport Mosque, but has the imam of said mosque ever even been questioned, investigated or arrested? No, they all whined about hurty feelings after angry locals threw things at the mosque, and were comforted by Liberal Lefty Locals who rushed to volunteer to clean everything up for them, like good little dhimmis, while the Angry Locals were arrested.

…”the city is in Lockdown…”

Why? Are the muzzies queuing in cars waiting their turn for a bit of ‘kill the whities?’

Vehicular Jihad: one of the many approved jihad methods for killing unarmed infidels at minimum risk to yourself, in order to gain your entry ticket to “Paradise”. Other methods include Rape Jihad, Food Contamination Jihad, Medical Jihad, Shooting Soldiers While They Are Having a Tea Break Jihad, Baby-Strangling Jihad, Setting Fire to Churches during Services & Shooting the Christians as They Come Running Out Jihad, Throat-Slitting & Beheading Jihad, Throwing Grenades into Churches Jihad, Pushing Infidels into Rivers & Canals Jihad, Putting Drugs into Pub Drinks Jihad, Stabbing Little Girls Jihad, and myriad other methods.

Schoolboy Jihad includes picking a fight with a British classmate before the whole school, then running away, returning with carloads full of Muslim Men armed with clawhammers, who attacked the unarmed Briton, bashing his skull to cause permanent brain damage, then all piling back into their cars and driving away. The school authorities said they could do nothing in response, except give the Muslim boy a severe detention… of 3 hours.

Henry Webster was the English schoolboy’s name, if I remember correctly.

I haven’t seen any actual images but various German acquaintances of mine claim this “40 year old German” was dark-skinned and had a black beard (in rather sarcastic tones, as we’re pretty used to these kinds of official lies¹).

¹ Recently, a German ‘expert’ demanded that the man who was responsible for the Aschaffenburg knife attack shouldn’t be tried for murder because, due to a “psychic illness” (details to be kept secret to protect his privacy), he was not mentally competent enough to understand that killing people with a knife is a crime.

Bless him, what a life the poor fella has. He should be put out of his misery.

Oh and let me guess he refused to take his meds because he did not like injections.

This black car that drove itself into the crowd can only hinder Germany’s self-driving car development program – unless it was a Tesla of course…

Without wishing to detract from the crime itself, I find the response from the police that they “asked the public to stay away from the downtown area and keep inside their homes” as rather frightening. Have the police got used to telling people to stay inside their homes? Clearly nobody wants gawkers wandering around the scene of the crime but having many eyes open for suspicious behaviour if the police are hunting someone is more useful than locking everyone up at home. I wonder if an announcement was made later that people could leave their homes.

Whoa, wait just a cotton-pickin’ minute!!! (as they would say across the Pond)

What on earth can Eugyppius be thinking by making this statement:

“I at least wanted to confirm that, contrary to many social media rumours and the all-too-familiar nature of today’s events, what happened in Mannheim was neither an act of Islamist terrorism nor another instance of migrant violence.”

NO, Eugyppius, you have not confirmed that at all. This “German man” could be a zealous convert to Islam for all we know, or more likely a mind-controlled Globalist assassin, sent to perpetuate the Myth of the White Terrorist.

See how the “hero” in this staged terrorist act is THE MUSLIM TAXI DRIVER named Azfal M. (a name common in the Indian Subcontinent. Notice they don’t elaborate on the “M.” in case it stands for Mohammed), who “pursued him to the Spatzenbrücke“?

So Evil White Terrorist kills White People using his vehicle as a weapon, and is chased down by Good Muslim Taxi Driver Immigrant Hero???

Gosh, how convenient for the Globalists!!!

Just like that Fake Breivik in Norway, raged against Muslim Immigrants in his “manifesto”, then murdered 77 Indigenous Norwegian teenagers at a summer camp, without attacking any mosques, or harming a single hair on a Muslim’s head.

Already the press will start lauding the Muslim Taxi Driver as a Hero chasing down the Evil White Terrorist.

Death driver of Mannheim! Alexander S. shot at his pursuers, then turned the gun on himself

“Alexander S. flees after the crime. But taxi driver Afzal M. reacts with presence of mind. He immediately takes up the chase with his car. The taxi driver’s boss says to RTL.de: “Our driver stopped the alleged perpetrator near the labor court.” Alexander S. then got out and shot at the taxi! Fortunately, the taxi driver was not hit, reports his boss.”

I can’t really pin this down but this guy decidedly doesn’t look German to me. Vaguely Turkish, but not really either. It would be interesting to know the surname (Why is that kept secret, anyway? Everybody could immediately place it?) but Alexander principally suggests an eastern European origin. For as long as the police hasn’t come clean on this, ie, until we know who this guy really is and who is parents were, I’ll continue to suspect that there’s something fishy about the official story we’re not supposed to know about.