Last week, a particularly controversial article written by David Hansard was published here in the Daily Sceptic. The article, in which Hansard was reflecting on the recent imprisonment of Sam Melia for distributing “racist stickers”, argued that we should accept limitations on speech when it comes to the “stirring up” of racial hatred, suggesting that to do otherwise would be “reckless” and a form of “hardline libertarianism”.

As a result of that article, elements of social media were themselves stirred up into a brief period of political hatred against Toby Young and the Free Speech Union, on the basis that Hansard’s article must have represented Toby’s views, and by extension those of the FSU – which as Toby has pointed out it emphatically did not. For those interested in the details of the débâcle, it was discussed at some length on last week’s Weekly Sceptic. This article is my attempt at engaging in a broader discussion of why ‘stirring up’ offences are wrong, largely from a historical perspective.

The brief facts of the case are that Sam Melia was convicted and sentenced to two years in prison, principally for “the intent to stir up racial hatred” under the Public Order Act 1986 Part III. The case, widely reported, concerned his production and distribution of stickers through a Telegram channel called the “Hundred Handers”, with stickers including messages such as “Reject white guilt” and others such as “Why are Jews censoring free speech?”

I perused these stickers back in 2020 when the “Hundred Handers” came to public attention, and my impression was that their creator had likely been influenced by the worldview of the National Socialist Party of 1930s Germany. It thus came as no surprise when it emerged that Melia had in his home “a poster of Adolf Hitler and a Nazi emblem”. Given this, I wouldn’t be surprised if Sam Melia were in favour of utterly pernicious policies and laws that would upend all our basic freedoms (including speech rights) and impose a race-based socialist order on the country, or the entire world if he could – but free speech doesn’t mean merely the freedom to express those views we like.

The 1986 “stirring up of racial hatred” law under which Sam Melia was convicted (which was expanded in the 2000s to include hatred on grounds of religion and sexual orientation) is a clear example, as I will explain, of state overreach; but the principal objection I have with those such as David Hansard who support this and similar laws is that they offer no principled reasoning as to where the limits of state power ought to be set in relation to the prosecution of speech crimes. Once we’ve accepted this much, what’s to stop us prosecuting stirrers-up of “climate denialism”, since climate change is supposedly an existential threat? (And demands to enact such laws have been made.) Or what about criminalising critical discussion of novel coronavirus vaccines on the grounds of public health? (We’ve seen the extrajudicial efforts to control such views already.) And perhaps not so far away, we might see an anti-‘Islamophobia’ law come into force. The doleful list can, and will, continue.

But defenders of ‘stirring up’ offences can offer no coherent argument as to where the limits on state power ought to be set in relation to inflammatory or contrarian speech, since such power is fundamentally wielded ad hoc, dependent not on any definite and unchanging standard such as the likelihood of an imminent breach of the peace (as was previously the case in English law and is the case in U.S. constitutional law), but rather on arbitrary assessments based on the political and social conditions of the day and what is perceived to possibly threaten public order at some indeterminate point in the future, or what might in the eyes of some affect the wellbeing of a particular group – or any perceived threat that might emerge in the future, such as the coming of the four horsemen of the political apocalypse.

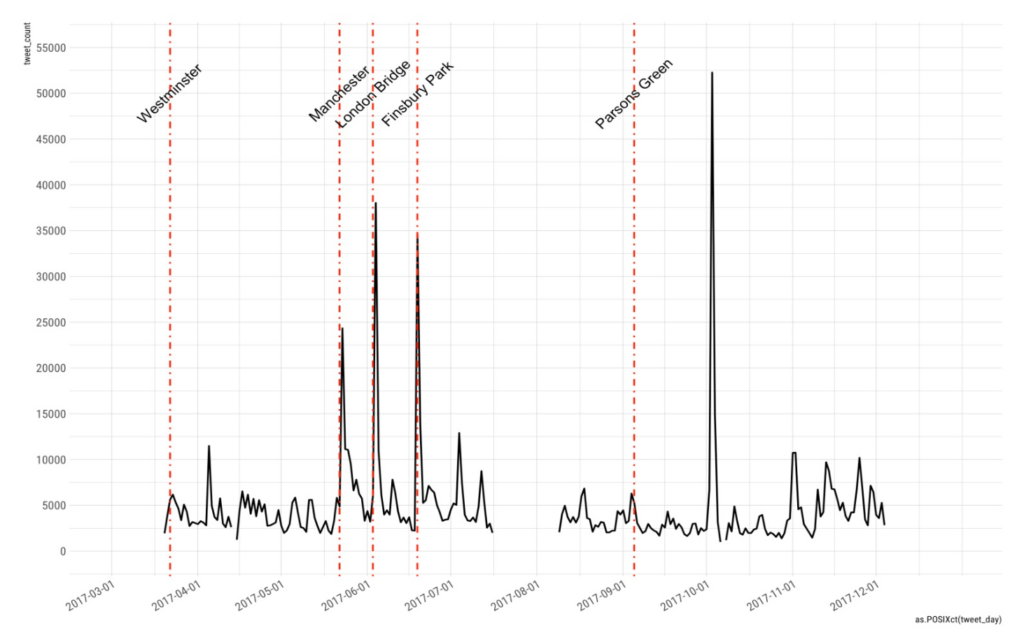

Nevertheless, to justify intervention, a causal link between inflammatory or contradictory speech and societal harms (such as violence) is generally assumed. In this vein, Hansard talks about the “costs” of “untrammelled [speech] freedoms”, but without feeling the need to provide any evidence of any such costs. In another rather typical example, hate speech is talked about as a “pernicious problem”, with a graph showing spikes in “anti-Muslim hate speech” following terrorist atrocities:

This “hate speech” is found to be associated with violent crimes against Muslims (with causation being implied), without any seeming recognition of the obvious fact that any violent crimes could more reasonably be attributed to the terrorist events, not the hate speech that arose following those events (which any normal person would also attribute to those terrorist events). Indeed, from psychology and common sense one could make precisely the opposite case from the one being proposed: that this ‘hate speech’ might in fact be a way for people to let off steam, thus reducing violence in the aggregate. Whether or not that’s true, the argument gets scant consideration, if any.

In the case of Sam Melia, in convicting him and giving him a very stiff sentence, the state can congratulate itself for reducing the hate speech coming from Sam Melia. But has that done anything to alleviate the grievances (real or imagined) for why Sam Melia wanted to distribute his stickers in the first place, or reduce similar feelings in that section of our society? Judging from the social media responses to David Hansard’s article, I doubt it. Weimar Germany had very strict hate speech laws that Hitler used not only as evidence of the truth of his views but also to attract crowds to his speeches. And did support for the BNP rise or fall following Nick Griffin’s appearance on Question Time? Did the neo-Nazi march through the Jewish neighbourhood of Skokie, Illinois fan the flames of Nazism in Illinois? These are more than just rhetorical questions, but cut to the heart of the matter.

In other words, the arguments for ‘stirring up’ laws are both totalitarian (having no limiting principle) and also typically lack a coherent evidentiary basis. Nor do they account for the possible opportunity costs, particularly in areas like science where enforced groupthink means stagnation at best. It’s raw power and prejudice, and damn the consequences.

But how did we come to lose our vaunted freedom of speech in this country (perhaps the most stable democracy that the world has seen until now, despite the pesky opinions of some of its citizens), when our colonial common law cousins have managed to keep and strengthen the laws protecting their speech – and with scarcely any discernable ill effects, too?

In discussing this, I’m speaking specifically about the kind of speech that could be called ‘inflammatory speech’ (distinct from, say, obscenity or defamation). This is what we’re generally referring to when we talk about freedom of speech. In its broadest sense, ‘inflammatory speech’ encompasses everything from trivialities like expressing a disdain for women’s sports up to and including expressions of support for the Holocaust. It’s quite often just ‘hurty tweets’, but sometimes speech can be so inflammatory as to provoke even the most unflappable into violence. Who could blame Jacob Rees-Mogg if he, after two or three sherries, were bestirred to fisticuffs by ungentlemanly remarks about nanny?

In England and Wales, speech likely to occasion a breach of the peace has been unlawful since time immemorial (and by statute since 1361). A breach of the peace occurs:

…whenever harm is actually done or is likely to be done to a person or in his presence to his property or a person is in fear of being so harmed through an assault, an affray, a riot, unlawful assembly or other disturbance. It is for this breach of the peace when done in his presence or the reasonable apprehension of it taking place that a constable, or anyone else, may arrest an offender without warrant. (R. v Howell [1982] QB 416.)

In short, an arrest could be made when there was a “reasonable apprehension” that harm was “likely to be done”. Leaving aside other possible forms of “disturbance” and focusing on speech alone, we see the clear necessity of the connection between the words spoken and the likelihood of physical harm (such as an act of violence against a person) for the speech to be unlawful. There was no notion that an offence could be committed simply by inducing in someone else’s mind feelings of hatred towards another person or category of persons.

There is a fundamental principle here that even a child can understand: you can say what you like, until what you say leads others to violence.

However, throughout history there has always been a tension between individual speech rights and the (sometimes very legitimate) interests of the Crown and its ministers to protect the overall security and peace of the realm. The Treason Act 1351 criminalised “imagining the Death of our Lord the King” (although it was generally only indictable following an overt act), and other laws such as Scandalum magnatum (prohibiting ‘fake news’) or heresy could be used in particular cases. Licensing laws, which required prior approval of any publication, were in vogue in the 16th and 17th centuries, being eventually replaced by the seemingly de novo common law offence of seditious libel. All of these laws had their time in the sun, and replaced each other in turn as the public mood (or jury nullification) dictated, and all except the Treason Act have now disappeared.

Of all these, only the law of seditious libel bears true relevance to the case of Sam Melia. Yet even here, with this illiberal law that was greatly defanged following the unsuccessful trials of William Hone in 1817 and which was finally abolished in 2009, the law required the prosecution to show, at least nominally, that the libel had an “intention to incite to violence” (Boucher v The King (1951) 2 DLR 369, cited in R v Chief Metropolitan Magistrate, ex p Choudry 3 WLR 1987). That is to say, “nothing short of direct incitement to disorder and violence is a seditious libel” (Sir James Stephen, History of the Criminal Law, vol. 2, 1877).

In other words, there had to be some cognisable and realistic connection to actual physical harm, not some vague possibility of a random person being ‘stirred up’ in their thoughts or emotions such that they might later on do something unspeakable. But the law as it stands today under the Public Order Act 1986, and in the case of Sam Melia, does not require the intent to incite violence or disorder. So, once again, how did we get to the point where our speech laws became unmoored in this way from any real risk of physical harm, such that the police will arrest someone for expressing gender-critical views or visit a person’s home to “check their thinking” because of an entirely subjective claim of emotional distress on the part of a ‘victim’? The state threatening violence (i.e., arrest and imprisonment) for things that do no physical harm is really an inversion of the “breach of the peace” standard that was such a thread through English legal history that it still survives in s.4 of the Public Order Act 1986.

Sadly, like so many regrettable things, it was done with good intentions: it was an attempt to remedy the fractious state of race relations following the influx of migrants that began in 1947-8, and following the failure of the law of seditious libel to contain public disorder directed against Jews (R. v Caunt [1947] 64 LQR 203, Birkett J).

In the midst of these tensions, the Labour Government of Harold Wilson introduced what became the Race Relations Act 1965, which in clause 6 created the criminal offence of inculcating in the mind of another person a feeling of hatred towards a particular racial or ethnic group, decoupled from any actual likelihood of violence or the threat of violence. This was a momentous change, leading us down the slippery slope towards our current free speech crisis. But in arguing for this new law, the then Labour Home Secretary Sir Frank Soskice attempted to placate the fears of the opposition as follows (HC Deb 3rd May 1965):

I would earnestly ask those who entertain sincere anxieties as to whether this involves an unjustifiable infringement of the liberty of free discussion to consider again whether their anxieties are justified. What is the loss of liberty they fear? I know that they will accept it from me that I do not mean this provocatively. Is it other than the loss of liberty by the use of outrageous language, not privately but publicly, to seek to stir up actual hatred against mostly completely harmless groups of people in this country for something they cannot possibly help, namely, their origin?

I do not believe that if, as I hope, I have fairly stated the position, hon. and right hon. Members should entertain those anxieties. I completely respect their sincerity. But would they on reflection, really wish to retain such a liberty in so far as the existing law allows it? I am positively certain that there is no hon. Member of the House who would dream of wishing to exercise it. I said insofar as it is allowed under existing law.

Our common law, as interpreted in his summing-up to the jury in the well-known Caunt case by the late Lord Birkett, provides that to seek to promote violence by stirring up hostility or ill-will between classes of Her Majesty’s subjects is a serious criminal offence punishable by imprisonment. The common law offence requires an intention to stir up disorder. When hatred has been stirred up history, unfortunately, shows only too clearly that violence and disorder are probably not far away.

Clause [6] substitutes an intention to stir up hatred for an intention to stir up disorder. That is far from a momentous change. [emphasis mine]

The final paragraph is a great example of rhetorical legerdemain, since the law for the first time made citizens in some sense responsible purely for the feelings of their fellows, on the very flimsy assumption that if there is hatred then “violence [is] probably not far away”.

The Conservative Opposition understood that the proposed Bill was very much not “far from a momentous change”. Quoting W.R. Rees-Davies in the same debate:

On that point, does the right hon. and learned Gentleman not recognise that this particular matter is absolutely plain? Hatred is not in any way linked whatsoever to the creation of a breach of the peace or a public disorder. Clause [6] does not relate to them at all. The right hon. and learned gentleman referred to them being likely to stir up hatred, but says nothing whatever as to whether there was any likelihood of a breach of the peace. That is what is wrong with it.

And the question might have been asked, that once hatred in the mind of the public were regulated, why not other feelings, such as hurt and distress? This is, of course, what has happened.

Following the Southall riots in 1979, a review was conducted into the public order legislation. The ostensible basis of the review was to prevent actual public order disturbances. Yet, under this cover, the Public Order Act 1986 s.5 made it unlawful to use “insulting” language in a manner likely to cause “distress”, absent even any proof of actual distress. In the words of the then Home Secretary Douglas Hurd, “we have abandoned the requirement of proof of actual alarm, harassment or distress” (HC Deb 13th January 1986). In addition, the Communications Act 2003 criminalised the sending of a “grossly offensive, indecent or obscene message” without the requirement that the message ever even be received by anyone, let alone perceived as hurtful.

My point is that when we abandoned the ancient principle that, in order to be criminal, words must lead or be likely to lead to violence or public disorder, we opened the floodgates to sweeping restrictions on speech that extend so far as to proscribe dogs doing Nazi salutes and (as far as anyone knows) did nothing to prevent any outbreak of violence. This is the key point that defenders of free speech should understand, and this is why the law under which Sam Melia was convicted is wrong.

That is not to say that the Government does not have an interest in maintaining the King’s peace. However, that interest is not compelling enough to warrant restraints on speech unless there is a genuine and imminent likelihood of a breach of the peace, which is to say “immediate [i.e., imminent] unlawful violence” (Public Order Act 1986, s.4).

In this regard we should aspire to emulate our common law cousins in the United States. Across the pond, the practical effect of speech laws did not differ so much from those in England until the great divergence in the 1960s. But they had the U.S. Constitution to protect them; and while we took one path, they took another – the correct one. I refer specifically to the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark ruling in the case of Brandenburg v Ohio [1969], in which the court held, following decades of contention over this issue, that:

The constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a state to forbid or proscribe advocacy [even] of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.

However in delivering this opinion, the court did little more than recapitulate what J.S. Mill had to say a hundred years prior, and what has long been a principle of law, until we chose to pull down this “Chesterton’s fence”:

An opinion that corn-dealers are starvers of the poor, or that private property is robbery, ought to be unmolested when simply circulated through the press, but may justly incur punishment when delivered orally to an excited mob assembled before the house of a corn-dealer, or when handed about among the same mob in the form of a placard.

I put it that Sam Melia’s speech did nothing to breach the King’s peace.

Ian Rons is the Honorary President of the Free Speech Union.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Professor, the thing is – this whole net zero, man-made-climate-change business is not about science. They do not care whether you are right or wrong.

Professor, the whole thing is about power and control.

It’s about you and me and just about everybody else being controlled by a small, elite group of politicians/criminals.

That’s all there is to it.

Marxism wasn’t about the liberation of the proletariat either. It was just a useful ideological tool to acquire total control over the entire population, to the extent where any individual could be summarily executed without any reason.

Nazism wasn’t about the superiority of the Germanic race either. It was just a useful ideological tool to kill as many people as possible – Jews, Germans, Russians, whatever.

Woke isn’t about addressing historical injustice either. It’s just a useful ideological tool to control and enslave people.

Professor, feel free to study the climate if that’s what you enjoy doing, there is no reason why it shouldn’t be done. But be aware of what’s going on, because, I’m sure as a scientist you don’t like the feeling of not knowing what’s going on.

Indeed. “Public health” isn’t about the health of the public either.

”“If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it. The lie can be maintained only for such time as the State can shield the people from the political, economic and/or military consequences of the lie. It thus becomes vitally important for the State to use all of its powers to repress dissent, for the truth is the mortal enemy of the lie, and thus by extension, the truth is the greatest enemy of the State.”

Joseph Goebbels

“And you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free” , John 8:32

It sure is a big battle but it is still worth fighting, all is not yet lost.

Indeed.

Ye shall know them by their fruits. Matthew 7:16

Fruits of Nazism: Death camps, Europe in ruins, 50 million dead

Fruits of Communism: – Slavery, death camps, 100 million dead

Fruits of wokery: ? We’ll see.

True….They are a threat to all working & middle classes in this country. People need to start resisting this and trying to get the message of what Agenda 2030 is to the wider public. Car manufactures need to show some backbone too instead of asking the Government for clarity in deadlines, like Jews in the 1930s helping the Nazis kill more of them, or Turkeys voting for Christmas.

True major major sir sir, but we don’t need to convince the “elites”(and I use the word advisedly).

We just need to wake up the normies, and we’re getting there.

Faced with serious and increasing pushback the political class’s unity on this question will fracture.

The whole climate change story is a hodgepodge of nebulous theories all of them so vague and unverifiable that they are impossible to prove or disprove.

All climate change predictions are couched in words like could, might, possibly.

And even those are consistently wrong. No polar ice in the summer, Maldives under water. All not even remotely accurate.

The whole thing is just the biggest scam of the last 30 years.

None of this work will be reported in the mainstream

Too many vested and powerful interests hold sway over the MSM.

There are people who are very invested in the Net Zero project, some of whom might even believe in it. But many of its supporters cannot backdown now, no matter what contradictory evidence is presented to them. There are others who are using it to simply control populations. Both petty and serious authoritarians are delighted with Net Zero.

But the ever increasing evidence that challenges Net Zero, cannot be ignored forever. Thus I expect to see a change of tack, away from CO2 as the bogeyman, to a more wooly notion that reducing consumption and consequently ‘saving’ the environment, is good in and of itself.

Levels of CO2 have been much higher in the past, with evidence of vibrant animal and plant life.

Anyone who has seen the destruction left by a herd of elephants munching their way through nature would wonder at how similar numbers of massive dinosaurs could possibly have survived. The answer was, of course, that CO2 levels at the time varied between 1,200 and 2,800ppm, i.e. three to seven times today’s level.

CO2 levels in the Cambrian period 540 million years ago were just under 8,000ppm, i.e. twenty times today’s value.

Temperature data going back billions of years show that average global temperatures have varied by more than 10°C in either direction and that the Earth is currently in one of the coldest periods in its history. No geological period has been as cold as our current period, the Quaternary, for at least 250 million years. (See ‘Inconvenient Facts’ by Gregory Wrightstone.)

Not only that, but CO2 levels are often artificially increased in greenhouses to accelerate plant growth, often done by exploiting the exhaust of gas fired heating.

I don’t like the “trapping heat” explanation of the greenhouse effect. So what if more heat is trapped in the upper atmosphere, why should I care about that on the surface?

A better argument in my view is to consider the energy striking the ground, some (a lot) of which comes from the atmosphere, which is why cloudy nights are warmer than clear ones.

Downwards radiation from CO2 molecules comes from an effective height, below which the infrared photons have a good chance of avoiding absorption before striking the ground. Adding more CO2 must reduce that effective height, increasing (usually) the temperature, giving more downward radiation at the surface.

Hence, saturation is a myth.

Saturation is most certainly not a ‘myth’, if only because it is only a hypothesis, as this article points out:

‘The saturation hypothesis would appear to explain how CO2 has been 10-15 times higher in the past without runaway temperatures, while the anthropogenic warming opinion does little more than provide scientific cover for a dodgy but fashionable extreme eco scare.’

This hypothesis is supported by workings:

‘Diffuse radiation depends on the different absorption bands of carbon dioxide and water vapor, as functions of wavelength, temperature, concentrations or pressure. The predicted results using COMSOL computer code show that the effects of carbon dioxide concentration on ground surface temperature are negligibly small, for example, over a 5-year period.’

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590123024015548

‘We used this setup also to study thermal forcing effects with stronger and rare greenhouse gases against a clear night sky. Our results and their interpretation are another indication for having a more critical approach in climate modelling and against monocausal interpretation of climate indices only caused by anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.

Basic physics combined with measurements and data taken from the literature allow us to conclude that CO2 induced infrared back-radiation must follow an asymptotic logarithmic-like behavior, which is also widely accepted in the climate-change community.

The important question of climate sensitivity by doubling current CO2 concentrations is estimated to be below 1˚C.

This value is important when the United Nations consider climate change as an existential threat and many governments intend rigorously to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions, led by an ambitious European Union inspired by IPCC assessments is targeting for more than 55% in 2030 and up to 100% in 2050 [1].

But probably they should also listen to experts [2] [3] who found that all these predictions have considerable flaws in basic models, data and impact scenarios.’

https://www.scirp.org/pdf/acs2024144_44701276.pdf

The best way for you to counter that hypothesis would be with your own workings, without which your ruminations, as with so much nut zero nonsense, simply add more hot air……

There seems to be conflicting evidence. So of the science appears to have an almost limitless budget, some of it doesn’t.

However, the simple irrefutable truth is that Mrs Jones the retired shop assistant living in the UK – and all those like her, including you and I, should bare no penalty as no action by us remedial or otherwise could possibly have any effect on Global CO2 or therefore climate change. And as such we are, ruining our economy, and our futures for …nothing.

Their terraforming plans have nothing to do with greenery. They aspire to a sandy desert world where silicon will reign supreme. The real target isn’t carbon dioxide it is carbon generally. If they see you going out for a drive with your big family then they are filled with loathing and homicidal tendencies. You are a vermin problem.

Perhaps someone could letMr Miliband know about CO2. He does not appear to understand the science. Perhaps he should as Zorofessor Willie Soon, an astrophysicist for advice.

Very well written, positively seminal in its field.

William Happer (Princeton) authored a paper published in 2020 on the saturation of the infrared absorption bands for the five most abundant greenhouse gases: https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.03098#

Its simple, telling to truth doesn’t get you billions of £s, dollars etc, it also doesn’t enable you to control the situation either , but the fact of the matter is, the Truth ultimately will come out and sooner the better in this country, before they either freeze or starve us to death!!.

Chris:

Shame on you for not referencing the original and most quoted paper on CO2 absorption: Wijngaarden & Happer (2002), which also notes that methane emissions are also a non-problem.

It just seems so unbelievable that so many people want to go along with the Net Zero scam, but then you look back to how so many behaved during the Covid period and then you understand and despair of the stupidity of it all

Not surprising as most people still trust the media and government

Nil illegitimi carborundum people.

Merry Christmas. Turn on all the lights.

‘What the scientists are looking at here is the narrow absorption bands within the infrared (IR) spectrum that allow ‘greenhouse’ gases to trap heat and warm the planet.’

I’m not sure Chris is making the saturation point correctly here. Incident solar radiation only in a certain frequency band is absorbed by CO2, and all the incident solar radiation in that band is absorbed by existing CO2. Therefore, additional CO2 produces no additional absorption, because there is no radiation in the pertinent band left to be absorbed.

What about the IR rerediated from the earth?

“studies suggest”? It’s beyond any shadow of doubt.