As new mortality data come in, it’s increasingly clear that something abnormal happened in the spring of 2021 when it comes to people dying of causes other than flu, Covid and other respiratory diseases.

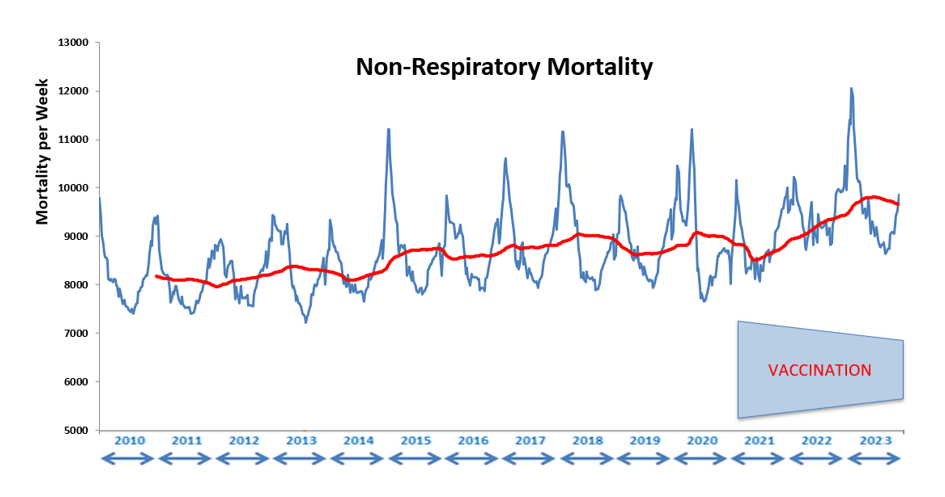

I have updated the non-respiratory data to the end of 2023, so there are now four years of Covid-era data included in it. The progression can however be traced back all the way to 2010, as shown below (the red line is the running 52-week average), and the sharp rise from early 2021 is now clear as day. Whatever is behind this has caused a rising trend in non-respiratory mortality (NRM) that has now stabilised, but at a much higher level than before the whole Covid imbroglio began. In fact, 2023 showed the worst total non-respiratory mortality figures than in any of the three preceding years, at 9.5% above the pre-Covid 2015-2019 average. In recognition of this sorry reality, the ONS this week said that life expectancy has gone backwards by 12 years to 2010 levels.

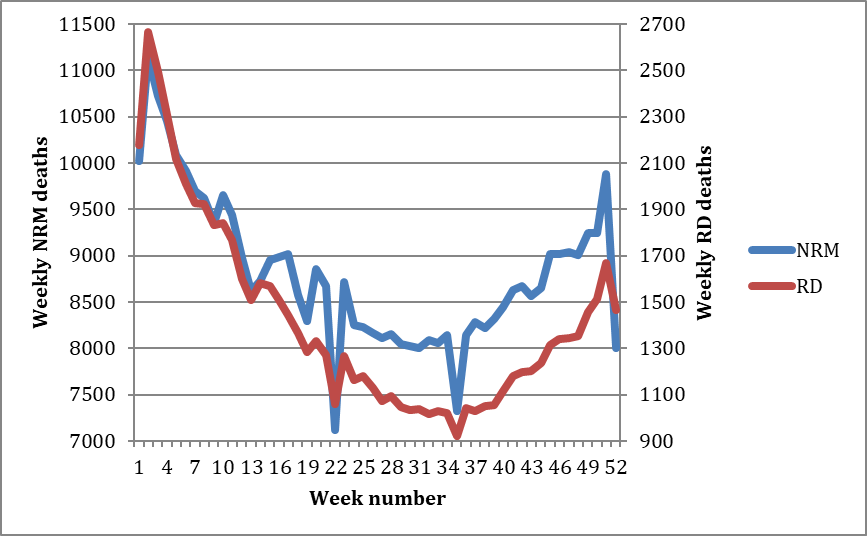

Take a look at the chart below, which shows the NRM pattern during the period 2015-2019 as well as the corollary for respiratory disease mortality (RD). Averages for each week are shown. The deaths from respiratory illness are by definition from acute disease, at least those that were properly registered as ‘died from’ rather than ‘died with’. The two lines match very closely in shape at least, the only real difference being the total numbers involved in each case (note the different range for respiratory disease on the secondary Y axis on the right hand side).

To emphasise this similarity further we can compare the ratio of non-respiratory mortality to respiratory disease mortality for each year from 2010 to 2019. They run like this:

- 2010 6.33

- 2011 6.16

- 2012 6.08

- 2013 5.82

- 2014 6.58

- 2015 5.98

- 2016 6.28

- 2017 6.26

- 2018 6.07

- 2019 6.36

Average for the whole period is 6.18.

The maximum variation in each year from the average proportion of NRM deaths to total deaths (average of 86.1%) is only 0.75% (up or down). This all goes to show that there is a strong consistency to the overall yearly figures, despite the large variation in weekly death numbers for both non-respiratory mortality and respiratory mortality over the course of each year.

NRM is clearly highly seasonal, so even though the bulk of these deaths arise from chronic morbidity, whatever it is that tips an individual over the edge to his or her demise varies over the course of the year.

My working assumption is that whatever factors drive normal seasonal variation in acute respiratory disease mortality are also responsible for a similar variation in the proportion of people dying from chronic disease during any given week of the year. The importance of studying seasonal variation as the main driver of disease variability was emphasised in a recent paper in the peer-reviewed Journal of Clinical Medicine, which strikingly found no noticeable effect on Covid incidence patterns from vaccines and non-pharmaceutical interventions but a clear link with the seasonality of coronaviruses.

The most likely common factor to search for is whatever causes a variation in the vulnerability of people to any form of external shock, e.g. a reduction in their immune defences. In the normal course of events this may for example be something climate related (e.g. cold weather) or perhaps depends on some other natural variables like sunlight intensity.

Could a man-made event that may have had a large influence on the immune status of large sectors of the population have changed the overall picture in a very different way? It may be a worthwhile exercise to look for such a signal in the mortality figures.

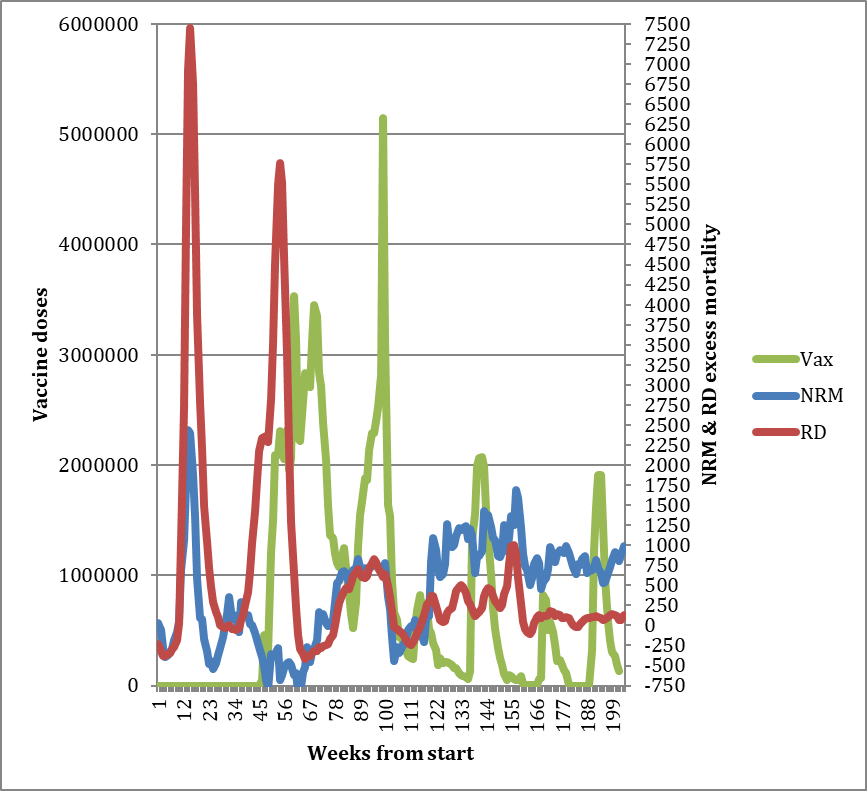

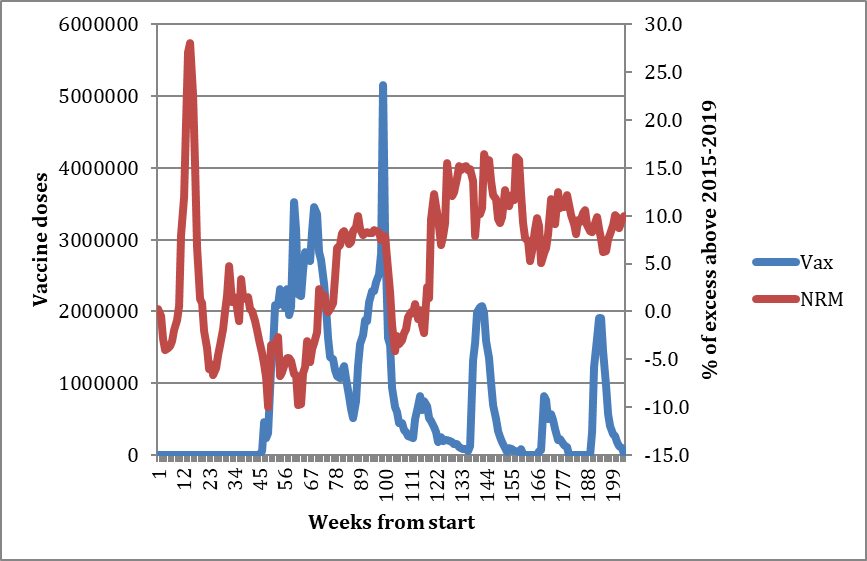

Turning to the Covid years, the chart below shows the excess mortality for both NRM and RD for the period 2020-2023, as well as the number of vaccine doses administered. Here we can see that the usual mortality patterns are at first completely disrupted, and this is consistent with the argument that a new pathogen which had never been encountered before had arrived and consequently had an outsize influence on acute mortality. However, by 2023 we can see that the ratio between NRM and RD has once again settled back to normal:

- 2020 3.27

- 2021 3.88

- 2022 5.86

- 2023 6.16

Average for the whole period is 4.49.

Already with this chart it is possible to see that, by comparing the different way the NRM and RD excess mortality responded to the initial Covid waves, the component of non-respiratory mortality derived from the after-effects of Covid itself (i.e., Long Covid) is probably relatively small. This is because NRM excess (blue line) was falling significantly – as expected due to mortality displacement – after the initial spike of deaths in the spring of 2020, even while the second RD spike (red line) was in full flood. This suggests that the after-effects of the first wave did not markedly increase non-respiratory mortality during the rest of the year.

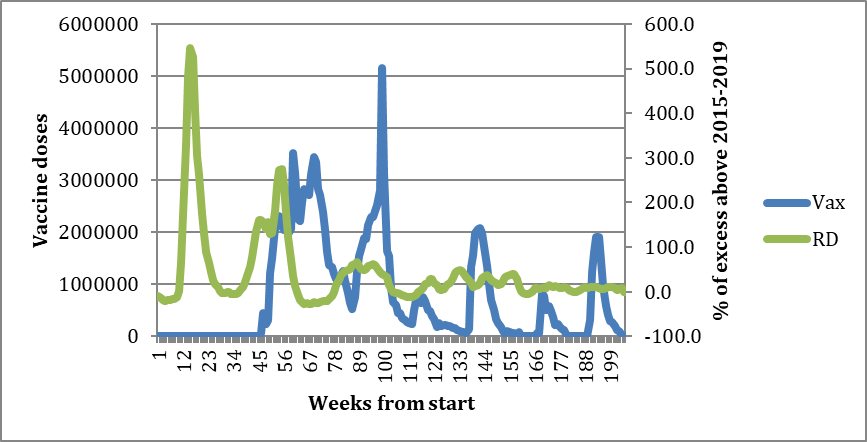

This is not the case with regard to the vaccination campaigns. To illustrate this one can look at the percentage changes from the 2015-2019 pre-Covid baseline for both non-respiratory and respiratory excess deaths (see charts below). NRM excess percentage (bottom chart, red line, right-hand axis) has been increasing year-on-year since the vaccine campaigns, whereas RD excess percentage (top chart, green line, right-hand axis) has been diminishing. The respiratory disease mortality has been falling despite the number of vaccine doses also falling each year. Note the different values on the secondary Y axis (right hand side) in each chart.

Vaccines delivered:

- 2020 75 million (doses one and two)

- 2021 40 million (dose three)

- 2022 25 million (doses four and five)

- 2023 17 million (doses six and seven)

Respiratory disease excess over 2015-2019 baseline (RD):

- 2020 91.3%

- 2021 62.6%

- 2022 13.9%

- 2023 9.9%

Non-respiratory mortality excess over 2015-2019 baseline (NRM):

- 2020 1.0%

- 2021 2.0%

- 2022 7.9%

- 2023 9.5%

The fall in respiratory mortality can perhaps best be explained by the attenuation expected from a gradual increase in population immunity to the new pathogen, and also by a declining virulence of the pathogen itself (e.g. the less deadly Omicron variant). But how does one explain the non-respiratory mortality changes, other than through a general long-term decline of the overall health of a population?

Unfortunately, it is still not possible to state with any certainty which component of the public health measures employed (vaccines or NPIs) can give the most plausible explanation for the bulk of the non-respiratory excess death phenomenon (assuming, as noted above, that the contribution from the virus by itself is relatively small). Many who have commented on these developments believe that the vaccination campaigns primarily caused the uptick. This can only be confirmed once the authorities release full mortality data including the vaccination status of all individuals at the time of their death.

The recent whistleblower data release in New Zealand provided in my view the strongest evidence to date of a temporal association between vaccination status and increased excess mortality. It is now all but impossible for the authorities to deny the link. If they want the public to feel safe about Covid vaccinations again, it is now up to them to disprove that vaccinations were causative in the excess mortality experienced over the last three years.

The key insight to be gleaned from separating overall mortality data into the two components of respiratory and non-respiratory disease is in recognising that both are subject to the same seasonal variability in population health vulnerabilities. They are coupled together such that as one rises, the other falls. This is presumably because they depend on the same pool of vulnerable people who are at risk of dying at any particular time.

Covid was a novel pathogen that in 2020 disproportionately increased respiratory mortality and thus, due to their synergy, pushed non-respiratory mortality downwards (part of the mortality displacement effect). Something then happened in 2021 that increased the size of the pool of vulnerable people over the following two years. The normal relationship between the two mortality types has re-established itself in 2023 (e.g. the proportion between them was restored), but at a level around 10% above pre-Covid mortality.

Total excess deaths for the four years (compared to 2015-2019) have now reached around 225,000, which should under normal circumstances lead to a fall of around 9% (i.e., 20,000) in annual deaths in subsequent years due to mortality displacement as deaths of the old and vulnerable are brought forward by some unusual event. Instead, what we see is excess mortality in 2023 reaching a new peak of 10.6% with currently no signs of slowing up. Once you take into account that instead of 9% fewer deaths we have 10.6% more, this adds up to a huge nearly 20% rise above expected levels. Welcome to the new normal.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Thanks for this article Nick. Though I think looking at the U.K. in isolation is no longer particularly useful. The work of Dennis Rancourt needs to be seen more widely. Now I just want the authorities to hand over the record level data, as Steve Kirsch has been asking for.

”If they want the public to feel safe about Covid vaccinations again, it is now up to them to disprove that vaccinations were causative in the excess mortality experienced over the last three years.”

I don’t quite get that sentence. You make it sound like there needs to be a course correction. It seems like a very “conditioned by the system” thing to say. If even half of what I now know about the vaccines were true, we are way, way beyond that. People need to be imprisoned, for a long long time. A lot of people. This is as far away from “silly me I made a mistake” as it’s possible to get. Starting with June Raine. Her criminal negligence is immeasurable.

There needs to be a wholesale overhaul of vast swathes of government. There should even, IMO be a peacetime equivalent of an international War Crimes Tribunal as occurred after the Second World War.

An overhaul will only happen with a change in government with none of the branches of Uniparty running it.

Yes. I’ve never felt more disconnected from politics. I’ve never had less interest in reading anything our newspapers say. Personally I’m not even thinking about the unaparty or who I’m going to vote for. The only way I will be able to re-engage is when establishment media start covering stories like the German farmers demonstrations, or the tunnels under the synagog in New York. When they start asking proper and due questions, like why were the police so quick to fill the crime scene with concrete? How can they even have ordered a lorry full of concrete that quickly? The mind boggles.

Indeed. Even just taking the whole “vaccination” thing from start to finish, including the dodgy trials, lack of scrutiny from regulators, vaxx passports, deliberately misleading claims, censorship, the scale and seriousness of the crimes is staggering. If you add in the rest of the folly and evil, I can’t think of anything comparable outside of wartime and events specific to a single country such as the Cultural Revolution in China.

For those who haven’t seen it yet, here is the Denis Rancourt data supporting his assertion 17m have been killed worldwide:

First a very short overview video:

https://x.com/denisrancourt/status/1745550503587495984?s=61&t=AY3dxo4CPswl6wmndLEhaw

Then all the data sources / papers:

https://x.com/denisrancourt/status/1745669516963574183?s=61&t=AY3dxo4CPswl6wmndLEhaw

“There should even, IMO be a peacetime equivalent of an international War Crimes Tribunal as occurred after the Second World War.”

Absolutely.

100% agree.

Presumably when you mention “Covid” it’s shorthand for “Covid-19” specifically; remember that many Covids have been common since records began, with a large chunk of “common colds” being of that kind. That said, perhaps the Chancellor will be content with the results – and the Treasury will still want to delay the start age for state pension payments. Maybe some actuarial analysis is in order.

Leaving money on one side, I wonder whether “Something then happened in 2021” had a lot to do with psychology, rather than simple infection effects?

Good point. A multi-jabbed relative got a cold recently. For some unknown reason they stuck a stick up their nose which tested positive so they ‘had to isolate’. I asked a) why test and b) why isolate; the answer came back – because they ‘didn’t want to put anyone else at risk’. Of a cold. In 2024. The psy-op fear-mongering propaganda has gone in deep amongst large swathes of the population.

It is perfectly clear that Non Pharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs) have caused this huge %age rise in Non Respiratory deaths to say nothing of lost education, rise in mental issues and ‘stay away from work’ malaise The Covid inquiry is a farce and is now to be stalled until after the election which is more obfuscation so that the public might forget the heinous lockdowns and the perpetrators of them – politicians, Civil sSrvants, NHS Managers are some of the ones that should be pilloried by a tribunal.

It is important to consider at what ages excess deaths are occurring.

And in any compare we need to take account of the increasing population (more population = more expected deaths if we don’t adjust), and ageing of the population (an ageing population means more expected deaths for the same population). We also need to allow for the improving mortality that was happening up to 2019 unless we can identify why those mortality improvements wouldn’t be expected to continue.

Adjusting for these things I’ve produced this chart for 5 year age groups of the percentage excess mortality which also shows these percentages for 2022, 2021 and 2020.

The data in these charts adjusts for population (by showing deaths per million in each age group) and ageing (though use of ONS 5 year banded population estimates and deaths in these narrow age bands). I’ve allowed for the projected mortality improvements from 2015-2019 based on the ONS long term assumption of 1.2% mortality improvement for all banded age groups. This assumption does accurately reflect actual improvements that were happening before 2020. I’ve excluded the 90+ age group as it is an unbanded age group and so the 1.2% pa figure doesn’t apply there.

I’ve based this all on the weekly registered death figures provided by ONS for England and Wales.

The 2015-2019 average is the only period for which we have comparable pre 2020 5 year age group figures; the weekly five year age grouped death figures came in from 2020.

Hence why the excess mortality is measured against that baseline.

As you can see there is excess mortality in every age group for 2023. In the age bands covering ages 30 to 54 it’s very roughly around 20%, so about one extra death for every five that we might have expected.

For completeness here is the chart with the percentages not allowing for expected mortality improvements from 2015-2019.

The excess mortality in the middle age groups is still shocking.

In the older ages it’s more a case that mortality improvements haven’t happened, but deaths have in 2023 occurred at around the 2015-2019 level instead.

Thanks for this – to my mind this is a far more important chart than the ones in the main article, as it identifies that those who didn’t need the jabs were hardest hit by them. Worth sending to TY as an article in its own right.

There ius no reason why data on death should not be available in near reak time, with no more than a week’s delay. Those few cases where the principal and secondary causes of death have not been determined or certified must be very small and can be a category of their own from which deaths are removed as data comes in.

That ever reason can there be for “the authorities [not] releas[ing] full mortality data” in full, omnline and within a week. IE data up to (say) last Friday should be available today. With enough additional data on the age and location of the death protected to ensure personal confidentiality, even outbreaks of poor hospital treatment and murderous GPs might show up earlier.

Exactly. At the start of lockdowns they were able to tell everyone how many people died the previous day, so why not now?

Rhetorical question, obv.

Farage/Dalgleish: https://youtu.be/9uV154LQ1J4?si=cn9nVrnnpgR64k8C

I’m surprised this is on Youtube. Maybe the dam is bursting.

Indeed, though sadly:

Nigel Farage 6 January 2021

This is why I shocked the world and backed Tony Blair on vaccines.

https://www.facebook.com/nigelfarageofficial/videos/why-did-i-back-tony-blair/732287214086772/

An excellent article, thank you

Got this from my MP the other day…

Dear Stuart,

Thank you for contacting me about the rise in excess deaths.

As you note, excess deaths – the difference between expected and actual deaths – have increased in the last year. There are several reasons for this such as high flu prevalence, the ongoing challenges of COVID-19, a strep A outbreak, and conditions such as heart disease, diabetes and cancer. The Government said it is attempting to reduce excess deaths now with additional treatments and diagnostic procedures, by delivering more health checks, and through its Major Conditions Strategy.

Extensive independent research shows that COVID-19 vaccines are extremely successful at preventing deaths. Each COVID-19 vaccine was assessed by teams of scientists and clinicians and all potential vaccines must meet the robust standards of quality, safety and efficacy set by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) before they are approved for use. Vaccines save lives and have allowed us to reclaim the liberties that we were forced to forfeit over the course of the pandemic.

As 93.6% of the population have had at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, there will be a high rate of vaccination in excess deaths. But that is different from causality. It is not the same as saying that vaccination is the cause of those deaths.

During a debate on trends in excess deaths on 20 October, the Government highlighted the responsiveness of the MHRA during the vaccine rollout, for example, by not offering AstraZeneca to under 30s and under 40s once very rare cases of concurrent thrombosis and thrombocytopenia were discovered.

Serious side effects are rare, however, given the hundreds of millions of doses administered across the UK. Infection from COVID-19 without vaccine protection remains more dangerous than getting the vaccine itself. I encourage the use of the yellow card scheme for reporting any suspected reactions or side effects. Where vaccine damage does tragically occur, it is right that individuals and their families can access payments via the Vaccine Damage Payment Scheme.

The coronavirus public inquiry will investigate the pandemic up to and including 28 June 2022. It must have the support it needs to ensure lessons are learned and mistakes are not repeated.

At least he replied. Mine – Chris Loder – now ignores me. He doesn’t like “being challenged.

Whoever this wa#ker is his name should be added to the criminal list. Quite clearly this is an official composite handed down from some executive department. As a way of confirming the MP’s guilt this letter achieves that aim admirably.

He is a bloody disgrace.

Thanks Huxley, That was my intention to obtain evidence of complicity and guilt. This is the latest in a series of similar emails.

Well done Stuart.👍👍👍

https://www.conservativewoman.co.uk/how-will-they-explain-away-these-latest-excess-death-figures/

And here is Kathy Gyngell’s shorter version.

Disturbing reading.

The age of the NRM is highly relevant, but this data tells us nothing about that.

I’m no expert but I do take a close interest in “all things Covid” and everything I have seen indicates that large numbers of younger people in their 20s – 60s – who you would normally not expect to be dying “unexpectedly” or in large numbers – are doing both. In ALL the highly-jabbed countries.

I am sure the jabs are causative, but I also wonder if the growing reluctance of medics to give antibiotics in a timely manner might also be an issue? There have been two deaths recently at the local hospital from sepsis where they had to admit liability, one in their 50s and the other younger.

Could it be a double whammy of jab plus poor treatment ?

I would recommend you read “The Bill Gates Problem” by Tim Schwab. It could well be that he is the source of all the covid insanity. The book describes the incredible power & influence that Bill Gates has developed through the Gates Foundation philanthropy that focuses on vaccines. He clearly states that vaccines will solve all the world’s health even though he has no depth of knowledge or experience in health-care. Gates has built a virtual monopoly controlling & influencing even governments, big pharmaceuticals, ALL research into vaccine development and main stream media. He controls the WHO. Bill Gates is an oligarch with so much power and influence he dwarfs Soros spending billions annually. . Of course he sells himself and spends millions to develop the narrative that he has saved millions of lives. Nobody will say, criticize or do anything to attack the Gates narrative for fear of being destroyed.

Excess Deaths Oral Question in the House of Lords

I asked an Oral Question about this on Thursday. The ‘question standing in my name on the order paper’ was: Lord Strathcarron to ask His Majesty’s Government what assessment they have made of the level of (1) excess deaths not attributable to COVID-19, particularly coronary and vascular-related excess deaths, and (2) excess deaths in younger age cohorts, since 1 January 2020.

Here is the exchange: House_of_Lords_11_01_24_11_06_20.mp4

I asked an Oral Question about this in the House of Lord yesterday. The ‘Question standing in my name on the order paper’ was:

Lord Strathcarron to ask His Majesty’s Government what assessment they have made of the level of (1) excess deaths not attributable to COVID-19, particularly coronary and vascular-related excess deaths, and (2) excess deaths in younger age cohorts, since 1 January 2020.

The exchange was:

House_of_Lords_11_01_24_11_06_20.mp4