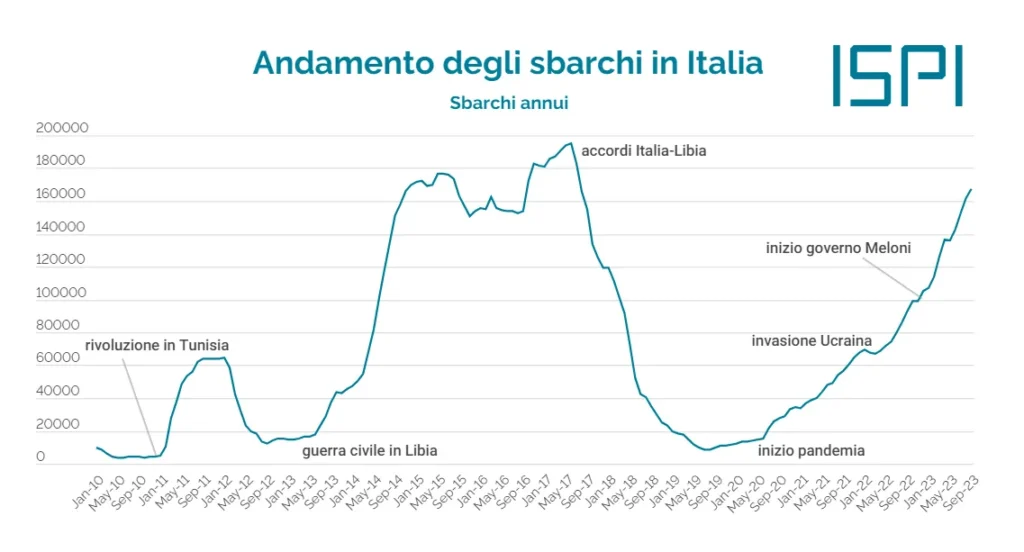

Europe has entered it second great migration crisis since 2014.

Numbers are now at levels not seen since the aftermath of the Libyan civil war in 2014. Here, from the Italian Institute for International Political Studies, is a graph of migrant arrivals in Italy from January 2010 through September 2023:

EU statistics confirm the extreme situation: Before the end of 2023, the EU, Norway and Switzerland together are projected to receive more than a million asylum applications, and therefore to meet or even exceed the 2016 record of 1.23 million. Germany alone has seen a 74% increase in applications compared to the same period in 2022; only Latvia and Estonia have faced higher pressure, due to migration from Belarus caused by the war in Ukraine. So far, the EU, which is entrusted with the security of European borders, has reacted with tepid half-measures, proposing to fast-track the approval process outside of Europe for those applicants with the least chances of success. This is expected to affect only a minority – perhaps a quarter – of migrants. The rest will enter the Schengen Area as before and live on state entitlements while their applications are processed over months and years.

The examples of Denmark and Hungary show that the migration policies of individual member states can have a dramatic impact on the settlement of migrants domestically. Both countries have taken a hard line against mass migration, and Denmark has seen their asylum applications fall by 56% compared to 2022, while Hungary has processed a mere 26 applications for all of 2023. There is basically no chance that the present German government, dominated by Social Democrats and Greens, will follow their lead any time soon. They are currently negotiating legal adjustments that will allegedly make it slightly easier to deport migrants whose asylum applications have been denied. Nobody believes this will change anything.

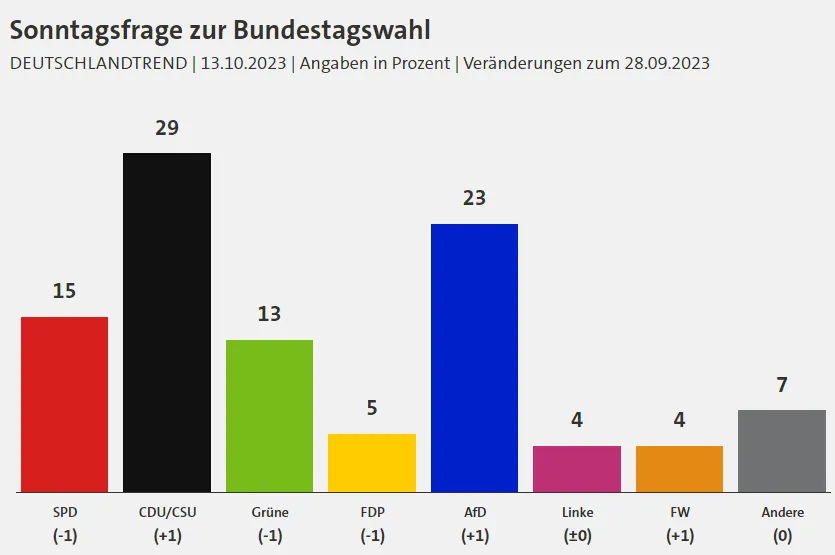

The latest polls show that migration is now the most important political issue for 44% of Germans. Despite wall-to-wall climate hysteria from the state media, environmental concerns now take a distant second place, predominating for a mere 18% of voters. The energy crisis of 2022 inaugurated the great German political volte face, and the migrant crisis seems poised to complete it. Collectively, the ruling parties of the “traffic light” coalition claim the continued loyalty of only 33% of Germans:

The media cannot suppress the migrant problem or talk it away, because the consequences are very immediate and extremely visible at the local level. Every last community has to find housing for the new arrivals. Generally they’re accommodated at first in school sport halls. In the longer-term, migrants receive housing rented by municipal authorities, which is expensive and in extremely short supply.

Reports, like this one from Focus, are all over the press:

In Rosenheim, things are getting worse. The situation is “extremely tense,” according to the district office. Every month about 100 people sent to them, either asylum seekers or refugees from Ukraine. These people are first accommodated in gymnasiums and later distributed.

The district currently rents about 280 properties, but it is “not feasible” to provide housing for 100 new arrivals every month. In addition, the occupation of the gymnasiums with asylum seekers and refugees is “a great burden for school and mass sports.”

District Administrator Otto Lederer (CSU) told FOCUS: “I am very dissatisfied with the asylum and refugee policy of the federal government. For example, the supply of adequate housing alone is a major challenge.” However, “integrating these people” is an even greater task that involves many problems.

Lederer’s clear message: “We are ready to take people in and integrate them, but there are limits, resources, for example, that are only available in limited quantities. Integration that doesn’t succeed because the prerequisites are missing is negative for both sides.”

In the meantime, the situation has “also had an impact on our society. Both for the local population, which is partly afraid of being overburdened, and for the refugees, who, when they come to us, can of course expect a certain amount of support,” says Lederer. He sharply rebukes the federal government: “You can’t set up additional voluntary reception programmes on the one hand and then leave the municipalities out in the cold when it comes to accommodation and integration.”

That report was from September, but nothing has changed since then. Yesterday, Reinhard Sager, the president of the German Municipal Council, said this in an interview with Tagesspiegel:

The fact that the wind has changed in the migration debate has not gone unnoticed by the Greens, but they have not responded to the change in mood. “The fact remains: an upper limit [on migration] is practically impossible to implement, undermines the individual right to asylum and contradicts the Geneva Refugee Convention,” wrote Green Party co-chair Ricarda Lang … Limits will “therefore not happen”.

It is true that upper limits would hardly be enforceable legally. But the Green realist wing around Vice-Chancellor Robert Habeck doubts that the party is striking the right note on the migration issue … In response to concrete proposals to alleviate the migration pressure, the Greens mostly express reservations or say no. They reject extending the definition of safe countries of origin to the states of North Africa, and they are at least sceptical about a switch to benefits in kind [instead of monetary entitlements] for asylum seekers.

Even the cautious changes of the EU asylum reform in the summer went too far for many Greens, who quickly condemned the compromise as amounting to a policy of “isolation and deterrence.” They simply deny that comparatively high German social entitlements constitute a “pull factor,” often claiming that this has not been scientifically proven. …

Losses in the state elections of Bavaria and Hesse apparently did not cause enough suffering to change any minds.

Left-wing Greens in particular emphasise that they have been in worse positions before, since they are in government both federally and in eleven federal states. But it is above all the realists who fear for the political relationships of their party and look to the coming year with queasy feelings.

The European elections are looming in June next year, and afterwards there will be state elections in Thuringia, Saxony and Brandenburg in September. The main issues will be “migration and the economy,” says a Green member of parliament. “If we don’t deliver on these issues, who will want to form a coalition with us?”

The answer is the CDU, if one can judge from the statements of their own politicians – even if doing so threatens to destroy the centre-right establishment. It has long been clear that the Greens regard their position in government not as an opportunity to strike compromises and ensure the longer-term viability of their party programme, but as a fleeting chance to shove as much of their vision down the throats of Germans as they can, until they’re finally voted out. Their leadership maintain the ethos of a radical protest party, and so we have no chance of anything changing until the next national elections in 2025. By then, they will have seeded a wide variety of social, cultural and economic problems that will continue to bear fruit for decades, even if they are banished forever to the political wilderness.

The political scientist Stefan Luft has given an interview explaining the longer-term political consequences of the migration crisis for Europe as he sees them. If the EU can’t stop the flood, more and more member states will begin a grand competition to worsen conditions for asylum-seekers, incentivising them to settle elsewhere. States that don’t withdraw entitlements from new arrivals would simply be punished, driving everyone ultimately to reinstate internal border controls and effectively suspending the open travel Europeans have enjoyed since the Schengen Agreement of 1985.

The political visions of allegedly fringe nationalist and Eurosceptic parties are thus on the verge of realisation, an inevitable consequence of the internal logic of the open-borders vision itself. Naturally, this will happen only after European countries have imported millions more poor, uneducated foreigners than they can ever realistically manage or integrate. In the meantime, there will be a scramble to undo the Merkel-era branding of migration opponents as right-wing xenophobes, not because this was always stupid, but because the future of the establishment left is at stake. Even solid majorities of German the Greens and the SPD demand tighter border controls. As the Danish Social Democrats have realised, pro-migration policies alienate the working class most of all, leaving the left with no voters beyond well-off, oblivious, environmentally obsessed urbanites, who exercise an outsized influence on media and academic discourse, but don’t amount to more than 10% of voters.

This piece originally appeared on Eugyppius’s Substack newsletter. You can subscribe here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

A remark for people not already familiar with the sight of The Walrus™: That’s one of the current leaders of the German Greens. The

ladywalking wheelie bin is not yet thirty and has famously never worked in all of her life. She went to uni, joined the student’s wing of her party there and then proceeded to becoming a career politician. She’s also mockingly called die grüne Tonne¹ — the green wheelie bin, after the green wheelie bins people in Germany have to use for organic waste.¹ Tonne is also German for ton.

Well The Walrus can certainly answer the question ‘who ate all the pies?’

I do hope she is fully boosted.

She is. She used to be a squad of COVID cheerleaders in the past.

😀😀😀

Damn you! I wanted to ask that question. Have an uptick instead.

Thank you 😊

So that explains why you can’t buy pies in Germany.

😀😀😀

One assumes so, since her voice was one of the louder ones calling for compulsory vaccination. This was shortly after she had attended and supported ‘my body, my choice’ pro abortion rallies.

If she is singing, then it’s clearly all over

👍

A parasite in other words

A politican of a parliamentary party republic (Germans don’t really elect MPs, they’re just allowed to chose their preferred party which is responsible for anything else).

Worth pointing out that although she attended university, she dropped out, failing to graduate.

That’s not really worth pointing out as she very likely never meant to achieve anything there beyond starting her career in politics. That’s how the German political class regenerates itself: People who are nominally university students join party student’s organisations there and work themselve upwards through the system, starting with the parliamentarism playpens (StuPa — student’s parliament and AStA, sort of a student’s government¹) which have been erected there for this very purpose.

¹ That’s not even the entry level as individual student’s hostels have microparliaments and elections for them, too.

I do not know, perhaps others do, does Germany run most of policy formulation and administration through quangos and NGOs to which successive governments appoint lefties.

one suspects the green-left policies will dominate for many years in net zero, immigration and much else.

This is a bit difficult to tell. There are quangos in Germany although the term itself doesn’t exists. Two prominent ones would be the RKI (Robert Koch Institut), the German equivalent of the UKHSA, and the so-called council of the economical sages (Rat der Wirtschaftsweisen) which produces economical advice and predictions (the government usually ignores). But pretty much all of Germany is a party fiefdom proportionally stuffed with members of the established parties (CDU/CSU, SPD, FDP, Greens and Die Linke [ex-SED]) down to the level of fire brigades.

At least the Greens (and also the SPD, which is very LGBTWTFy) don’t really have any policies of their own. They’re just imitating whatever the US-democrats currently propose, no matter how a bad a fit this is for German society. Eg, the German empire had a couple of colonies but these became all territories of somebody else with the treaty of Versailles 1919 and have thus been much longer governed by other countries (the German empire didn’t reach the age of 50 and didn’t acquire any colonies until it had existed for about 20 years). Yet, it’s the Germans who are supposed to be culpably responsible for everthing which happened there because they’re evil colonialists, too.

Another example would be that the current German minister of foreign affairs – the post being function-free party sinecure – Annalena Baerbock campaigned with the slogan Keine Waffenlieferungen in Krisengebiete!, in the name world peace, stop arms deliveries into war zones, but became a Send more arms to Ukraine! hawk immediately when Biden wanted this.

It’s probably a safe bet to state that Germany and Austria aren’t really states, just somwhat autonomous reservations for ethnic Germans and don’t really have governments, just central administrations acting on behalf of the so-called victorious powers (Siegermächte) which are mostly tasked with extracting money from Germans which can then be spent world-wide for whatever tasks the current US government wants to support without having to win a vote for that at home (or spending its own money, obviously).

Well it could stop illegals coming in if it wanted. Same goes for the U.S. Be like Poland, be like Hungary. Where are all the pro-Palestinian/Hamas demonstrations in those countries? Where are all the crimes perpetrated by people who are not shy in broadcasting the fact they hate you, won’t tolerate your beliefs/culture and want to kill or subjugate you? I have to share this guy again because he’s so spot on in his observations, his words being especially valid as he’s an ex-Muslim who sought asylum in Sweden.

( <2min ); https://twitter.com/JustLuai/status/1709881455625560327

This one he made due to him getting shed-loads of abuse and death threats from the ‘tolerant’ Muslims after posting the above vid;

https://twitter.com/JustLuai/status/1710604260696629656

We need to be identified they don’t !!..

“The media cannot suppress the migrant problem or talk it away”

But it never has been their job to do that. Their job is to report what happens and why.

They just don’t do their ‘job’. They are political organs or represent the views of those who have direct or indirect influence or control of them.

What a barge arse ! Make a good life raft though for her oh so precious cargo to cling to as they float Europe bound ! Do you think she has even met one of the Great Replacements, doubtful 🤨

The more interesting question is why won’t it. Why is Europe intent on suicide?

Because it prefers to have a sex life now over having a future in future.

It doesn’t stop migrants flooding in because it doesn’t want to. Remember that the EU is the star pupil in the global experiment of getting rid of National Identities so that everyone feels more like citizens of the world rather than citizens of France, Germany Sweden etc. The global government people at the UN and WEF see National Identity and Culture as an impediment to Global Governance.

Because multinational corporations require cheap labour.

Because globalists plan to crush British Judeo-Christian culture.

That’s why.

Christine Andersen MEP talked to MD4CE last week about this very issue. You can watch her blunt assessment of the situation in the EU here: https://rumble.com/v3oevrg-christine-anderson-mep.html

Human trafficking openly or secretly cash machine, Votes, Stupidity , Ideology & Evil.

It is worth noting

These high immigration figures also apply to the UK – they have soared since Brexit! So it is not an EU problem.

Despite immigration, the total population of the EU is almost unchanged. Germany and Italy both have falling populations with fertility rates well below replacement level.

Immigration is a problem but it is nothing to do with having too many people.

This may be true now, but just like the UK in say 1990, the population holds for a while, then it is up and up. I predict the same will happen to the European countries. How I wish the population of the UK was back at 55m.

“Not an EU problem”???——-But it is most certainly a problem caused by the EU. It isn’t just about numbers. It is about the cultural identity of Europe being transformed into something else. Liberal Progressives think there is NOTHING wrong with that and that turning all of Europe into Malmo is perfectly fine, but I think there is something very wrong with it.