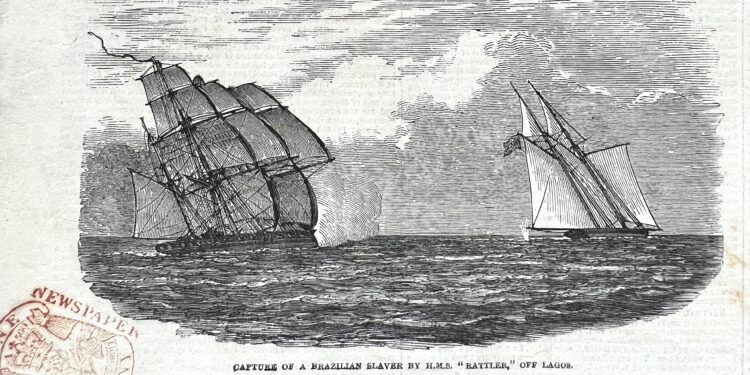

Our picture shows the Royal Navy’s HMS Rattler intercepting the Brazilian slave ship Andorinha off Lagos in August 1849 (from Illustrated London News, December 29th 1849).

The Restitution Study Group, speaking for black people who descend from the slaves that West Africa’s kingdoms sold to foreign traders, has been making the point that exporting of slaves to Brazil continued long after the trade to the Caribbean and USA had been stopped. HMS Rattler was the Royal Navy’s first warship with a screw propellor and famously towed HMS Alecto backwards in the Navy’s demonstration of propellor power versus paddlewheeler in 1845.

Rattler was thus well suited to intercept speedy American-built sailing slave ships during the Navy’s blockade of the Bight of Benin. The ILN’s correspondent described the chase:

About two o’clock we were nearly within gun-shot of [Andorinha], when – alas! how uncertain are the things of this life! – a dense mist set in, which obscured the whole horizon, and rendered her for a time invisible. Before the lapse of many minutes, however, she was again sighted by the officer of the watch; and as we had by this time gained so much upon her as to bring her within the range of our guns, we discharged three rounds from a sixty-eight pounder, the last of which, having fallen in rather dangerous proximity to her stern, caused her to heave to, after a most interesting and exciting chase of nine hours’ duration. Thus terminated the career of a vessel whose success is without a parallel in the annals of this revolting traffic.

This vessel was manned by a motley crew, consisting of 39 cut-throat looking fellows, exclusive of her commander, who was a Brazilian of note, and a Spaniard of distinction, nominally as a passenger. It was subsequently ascertained that this large American-built schooner, which exceeded 200 tons burden, had made 11 successful trips [carrying slaves], and had treble that number of escapes. She had been chased from time to time by most of the English and other cruisers stationed in the Bight of Benin, including some of our fastest sailing-vessels.

The narrative from Benin today is that the Oba (King) and his chiefs had abandoned the selling of slaves by the 19th century, just keeping a few to behead or crucify sometimes in honour of the ancestors, a custom which I described recently. It’s since emerged that Ojo Ibadan’s account of Benin’s monstrous regime was printed in at least three British newspapers in January 1899, a month before the South Wales Echo startled its readers with the same story.

Benin, its elites would like us to believe today, was peaceably independent in the 19th century and trading palm oil, ivory and other produce – and it must have back from the world’s museums its bronze artworks, so wickedly looted by the British expedition which deposed the Oba in 1897. But Rattler’s busy campaign in the Bight in 1849-50 undermines this story – West Africa’s slave-selling kingdoms were still in business in the middle of that century, exporting slaves where and when they could, Benin’s Obas not excluded.

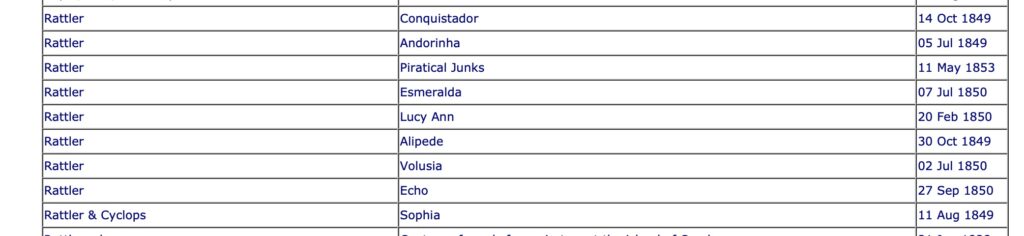

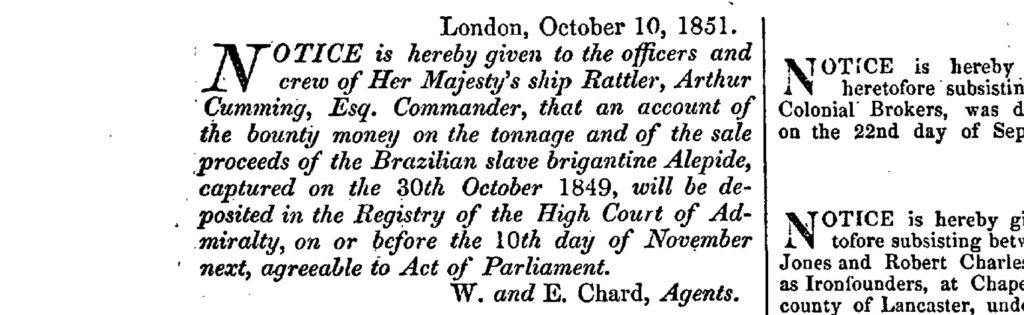

The screengrab above is from a remarkable list of “about 2,428 Slave Trade Vessels detained by RN Vessels &c” between about 1810-60, Rattler’s being mainly Brazilian-flagged slavers in the Bight of Benin (the “piratical junks” listed were from a later action with the East Indies fleet). The Alipede appeared, though misspelt as Alepide, in the London Gazette (October 11th 1851). Her master had been Antonio Cipro da Sa Bittencourt, she displaced a modest 90 tons, and after being judged at court in Sierra Leone to have been “equipped for Slave Trade” Alipede was forfeited and condemned to be broken up.

The same page of the London Gazette lists prize money paid to the crew of Rattler’s sister ship Pluto on the blockade for two seizures in early 1850. Royal Navy crews used to get their share of condemned slavers, allotted by rank, for the assessed value of the ship itself and also head money for slaves thus freed. This prize money was an incentive to the sailors, of course, but perhaps a fair reward for risk: thousands of them died of tropical diseases during the decades of the Navy’s blockade. The picture shows Rattler deliberately firing to miss Andorinha, as smashing the slaver with a 68 lb cannonball would sink both ship and slaves. The idea was to enforce surrender – humane, of course, though considering the prize money at stake, practical too.

Nigeria today is in a terrible state: last week its national grid – never robust these days – collapsed entirely, delivering 0% of electrical output for many hours. Governor Godwin Obaseki of Edo State (which includes Benin City) said while visiting Germany that Nigeria has enough bronzes for now. A fair point, considering the challenges of running any museum – not least its security cameras, alarms, climate control – and keeping its artefacts safe when you have no electricity. Siemens AG seems not yet to have produced the miracle intended in 2022, when a massive restitution of Germany’s museums’ Benin bronzes coincided with its multi-year Nigerian LNG and oil deal, following Siemens’ contract to overhaul Nigeria’s grid.

Remarkably, Nigerians still try to get to Brazil regardless of risk: in July the world was shocked by photos of four men who’d survived a 14 day ocean voyage to Vitória, the capital city of Epirito Santo, perched on the rudder of a cargo freighter (or in its trunking). Other stowaways survive the shorter hop to the Canaries using the same desperate method, while the shipping world debates how many may have been simply swept away and drowned. And how many of the 7,000 boat-borne migrants packed onto Italy’s tiny Lampedusa island this week are Nigerians?

In 2021 the Nigeria Social Cohesion Survey found 73% of its citizens wanted to leave. So without making tasteless remarks about rats and sinking ships, if even a proportion of these millions get their wish, in future more people of Nigerian heritage could see Benin’s artworks in the world’s museums than would ever see them in Nigeria – particularly as bronzes and ivories that have been restituted there so far are being locked up and hidden, at best. These are not merely commodities, unlike the slaves Africa’s rulers used to sell, and descendants of those slaves want them displayed around the world with full explanations of what was done to their ancestors. Art doesn’t of itself right past wrongs, but it can educate.

For foreign museum trustees and curators still to talk of entrusting their world-heritage collections to a country in such chaos is irresponsible. Even for those who accept the principle of returning artefacts, the only sensible course is to halt any talk of restitutions and offer Nigeria’s museums 3D-printed replicas of the precious works, which in the locked display cases they’ll need will be indistinguishable from the originals, and to wait and see whether conditions change.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

First take ze migrants, zen take ze bugs, zen rip out ze gas boilers, zen get on ze bicycles. —Ve have vays of impoverishing you and making you feel zo happy about it.

It’s not Ireland but look at this. Nasty, callous, treacherous b’stards! Damn right they need named and shamed. Zero budget when it comes to migrants, though, as if we need any reminders as to where their loyalties lie;

”Yesterday Parliament voted 348 to 228 to end winter fuel payments to pensioners. They were all Labour MPs.

Here is a video of every MP who voted for the measure. They deserve to be famous.”

https://x.com/DaveAtherton20/status/1833924307379945690

Knock all the green sh*t off the bills, then no need to bump up the allowances.

You ain’t seen nuthin yet Ron——Despite Miliband’s bare faced lies, bills are only going in one direction————UP UP UP——-Hey Miliband you are a f….g LIAR

I seriously don’t know how this feckin lot sleep at night.

We can all see Starmer sleeps very soundly.

He is not in the least careworn despite all the adverse exposure of the past two months and more.

He is loving every minute.

Take a good look at his face.

No empathy.

Compare Yvette ‘Allo Allo’ Cooper who is looking care worn.

Did you see the cheering when they won the vote? It was like England had just scored against Germany. Cheering because they have won the right to kill pensioners as indicated by their own study back when the Tories were thinking about removing the allowance, that said up to 4000 pensioners might die if the allowance was removed. ——Meanwhile migrants refurbishments including satellite TV will make sure the illegal aliens are nice and cosy this winter. I hope they chuck in a Netflix subscription as well since the poor vulnerable aliens should not have to be going without the latest films and TV series.

To be honest, I watched that clip a couple times and couldn’t detect cheers, only people shouting ”shame!”. But I see that after that decision was declared Lammy announced Ukraine needed a ‘few’ more million quid. Priorities…Anyone would think these sociopaths don’t have elderly parents themselves, but I guess freezing to death from hypothermia is just a working class problem;

”Wow. David Lammy just gave another 600 Million to UKRAINE. We are living in a clown world . Do you believe any of these clowns when they say they are fixing the foundations and can’t give heating allowances to pensioners.”

https://x.com/LeilaniDowding/status/1833928932367954398

There’s nothing wrong with living in the stone age.

Stone age peoples managed so we should be fine.

Anyone saying different do not pass go and go straight to the Scrubs for 18 months for being a Far White racist thug.

One of Ireland’s great charms and strengths is the Irish people.

Soon to be no more.

Bye bye Irishness and Irish people.

Maybe they need some dog and cat munching Haitians?

LOL.

PS. I have read numerous reports and seen a number of online videos saying this has been happening in Springfield Ohio the population of which was overwhelmed by an influx of 20,000 Haitians.

Maybe we should house some in the UK in Keir Starmer’s street or Angela Rayner’s?

I have the ideal place for Haitian criminals. —-No not prison. The Lion enclosure at the London Zoo.

The Government in Ireland recently signed up to the EU’s ‘Pact for Migration’, which makes migration into the EU continuous and permanent. The EU says that all member states must sign up to this pact and those that refuse their quotas will be fined a large sum of money.

Ireland is already swamped with migrants but they seem to want more. As their society continues to disintegrate it is likely to become like France with criminal trafficking gangs transporting migrants across the border into Northern Ireland. The UK is invaded from two directions.

There needs to be an emergency debate in the HoC about this issue.

We are not in the EU, allegedly, so why can’t we simply make companies pay tax on what they make here? Rules are made to be changed after all.

Any chance that Starbucks will give a warm spot and free coffee etc. to pensioners? We live in a poor world indeed when Labour MP’s cheer the fact they have succeeded in murdering Pensioners but do nothing about major companies making obscene profits.

It all depends on what the double taxation treaties say for legal persons domiciled or resident in a different jurisdiction.