In recent years, the rate of homelessness in California has grown substantially. The Golden State now ranks first among the 50 states at 4.4 per 1,000 residents, with LA and San Francisco often hosting vast homeless encampments (or tent cities, as they’re also known). I say “often” because these encampments are frequently cleared away by police, only to reappear somewhere else.

Many have blamed California’s homelessness problem on the cost of housing there. One prominent dissenting voice is the activist Michael Shellenberger, who has argued – most famously in his book San Fransicko: Why Progressives Ruin Cities – that it’s largely the result of untreated mental illness and addiction.

In June, Margot Kushel and colleagues at the Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative at UC San Francisco published findings from “the largest representative study of homelessness in the United States since the mid-1990s”. They interviewed 3,200 homeless people across eight locations, with effort being made to achieve representativeness.

So, what were the findings?

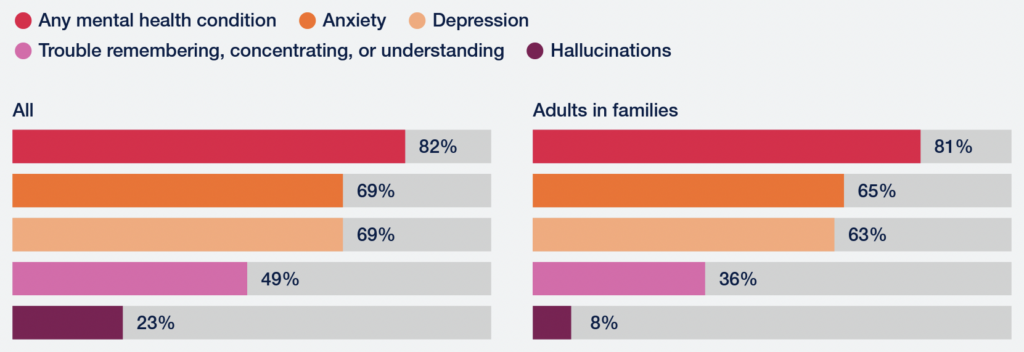

Remarkably, 82% of the homeless people in their sample said they’d had a mental health condition, and almost 1 in 4 said they’d had hallucinations (which are indicative of serious conditions like schizophrenia and borderline personality disorder). By contrast, the lifetime prevalence of any mental condition in the general population is only 46%.

The researchers also asked participants whether they currently had a mental health condition, and 66% said they did.

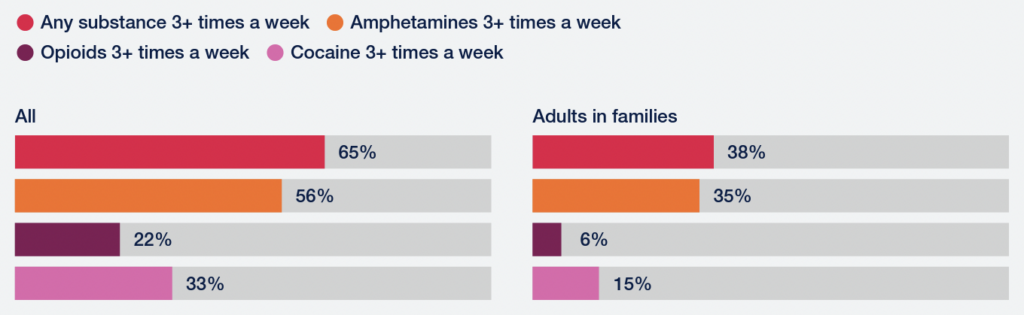

As for addiction, 65% of homeless people in the sample said they’d abused drugs or alcohol at some point in their lives. And among that sub-sample, two thirds said they’d done so before their first episode of homelessness. Which means that homelessness cannot have caused them to start abusing drugs or alcohol (more plausibly, it was the other way around).

The lifetime prevalence of drug abuse in the U.S. is around 8%, while for alcohol abuse its around 18%. Assuming that drug and alcohol abuse are completely independent (which they probably aren’t) the life prevalence of either is 26%.

Overall, the survey confirms that people with mental health conditions and a history of substance abuse are massively overrepresented among the homeless in California – consistent with Shellenberger’s arguments.

However, there doesn’t seem to be much correlation between the rate of homelessness and the prevalence of mental illness or addiction across U.S. states – which is wholly inconsistent with Shellenberger’s arguments. California is neither the most mentally ill nor the most addicted state.

What’s more, there does seem to be an association between the cost of housing and the rate of homelessness (which is hardly surprising). Indeed, homelessness is most common in liberal states that tend to restrict housing development, notably California and New York.

Here’s what appears to be going on: mental illness and addiction can help to explain which individuals become homeless, but they can’t explain why some states have higher rates of homelessness than others. Why so much homelessness in California? As the conventional wisdom says, it’s the cost of housing.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

“This summer, we’re taking bigger action against the Dairy industry than ever before, and we need you.”

“We’re fighting to make life more expensive and less pleasant for all of you! Who’s with us?”

Even better:

In the name of animal rights and to save the climate, we demand that all free-range cows, pigs, chicken, sheep, horses, goats and whatever other animals people may keep outside for the production of anything must be slaughtered! Here we stand, in our vegan trainers made of 100% unrecyclable plastic, ready take up the fight for a better future!

Methinks public lashings or something like this should be reintroduced. Some people are arguably to thick to understand anything but everybody understands Stop this or we’ll hurt you until you stop it.

I think it would be sufficient to invoke the age old British tradition of sending these morons to coventry.

As far as I can tell, this means declaring them non-persons who are generally ignored. I don’t quite understand how this would help. The guy who was interviewed here apparently believes he has not only a right but actually, a moral duty to force his personal delusions onto others with violent means (disruptive passively-aggressive means, actually). This means he’s in urgent need of an attitude re-adjustment.

Sending him to coventry means, by definition, no media interviews either.

I’m sorry, but by original design and uprising, I’m a rural simpleton. Assuming someone would burst into a pub in my home town driven by the zeal of a holy mission and start shouting stuff nobody wanted to hear, he’d simply get a sound beating. Repeat as needed until lessons have been learnt. IMO, that’s what’s missing here.

I would agree, but I’m an ex copper, and Fingal has already accused me of violence against my fellow man, despite him having no evidence.

Were I not an ex cop, I would probably have gone for ritual humiliation rather than a kicking. Being socially ostracised from every boozer in the area was pretty effective in our day.

Perhaps that’s why boozers are being forced out of business.

Evidence is irrelevant to Fingal and others of his kind

Would he have to ride there naked, on a horse?

Instead of giving them publicity and interviews whenever they pull these stunts? Well there’s certainly a precedent for it if the anti-lockdown protests against the human rights abuses are anything to go by. I never would have believed that the msm could so completely ignore something before 2020.

I’m only calling for equity. If they are allowed to disrupt the Jubilee, why are we confined to computer protest’s?

Watch the Pano-Drama where the BBC tried to take down Tommy Robinson literally by hook or crock. The presenter ended up getting ‘taken down’…Though not a squeak from the BBC.

There begineth the lesson of cancellation.

Yes. Some media do things like this. I know personally of one paper which has done that sort of thing. (Actually there’s another newspaper I know of that basically made something up too. Some parts of the media do seem to be more scriptwriting than journalism).

Did Tommy’s drama change anything I wonder?

‘publicity and interviews’… are guaranteed, at least on the BBC, since these folk are merely following Auntie’s narrative.

Can’t we send them to a very remote uninhabited Pacific island??

I always thought the Flannan Isles (West of Lewis) would do nicely for such purposes…

Gruinard.

We could find out if the anthrax weapon has been neutralised.

I would love to send all the wokes, rebellion freaks and lockdown lovers to Scotland and put the wall back up

Bikini?

Or into the Hulks.

Perhaps it would be better to reopen mental hospitals, as that is where these lunatics clearly belong.

Ah yes, and they can cause Bedlam to their hearts’ content…

The genuinely dangerous ones are still locked up in ‘facilities’. The rest are largely harmless and are just confused souls.

The problem is the criminal and drug fraternity seeking mental health as justification for their behaviour. Sling them in the ‘facility’ with the genuinely dangerous ones and mental health problems would likely nose dive.

This notion has much to commend it, until you remember how the Soviet Union used “mental hospitals” to “treat” those whose views were considered “unhelpful” by the state.

This is the problem with extreme treatment of those whose views you profoundly disagree. The very people who are genuinely a threat to society, British culture, whatever, may at some stage end up handing out the same extreme treatment.

We’ve already seen it. The treatment that the Fuzz have handed out to those objecting to mandatory covid jabs for kids has been orders of magnitude more severe than their response to BLM, XR, statue destroyers and the rest. No doubt with full backing from HMG, the “Opposition” and the Press.

So, whilst I think that, say, feeding these animal “lovers” to the pigs would be a punishment which fits the crime, you need to worry about who gets to make such a decision.

But it seems necessary that people who break traditional laws should be punished and that some effort be made to determine how they came to adopt literally lunatic views. Parents? Teachers? Illegal Substances?

And we must NEVER have woke senior police officers asking that road blockers be made “comfortable”. Immediate dismissal is appropriate.

25 people didn’t storm the Winter Palace

These people are not just unhelpful, they are destructive and dangerous.

Almost all of them have been sold off to housing developments; a consequence of “Care in the Community”

They would not stand out in Coventry.

And of course all wild carnivores must be hunted down to extinction.

The hooves of the Household Division would be quite persuasive!

Town-square pillories where the majority could let the eco-loons know how they’re generally viewed?

Interestingly, this snippet suggests that these devices could also tackle another modern problem…

“In the 1700’s, it was considered illegal for men to pose as women and women to pose as men. Offenders would be sentenced to prison time, and in addition to the prison sentence, they would be sentenced to time in the pillory.”

lashing?

how about hanged, drawn and quartered?

But although life will indeed be more expensive and less pleasant for imperfect humanity, their divine perfection will be ensured.

And they need us to help them, Mark – what could be more wonderful than to serve such a cause?

I think you’ve nailed their thinking.

It is a form of insanity. They may have been ‘captured’ by climate change, but have tied it together with all the un-holies of environmentalism and animal rights and forged something which is so far outside the reality of life that it beggars belief. I expect these are the same people who are face timing other activists on their iPads, ordering Dominos vegan pizza, and a new ‘slogan’ tee shirt off Amazon, and agreeing with each other that capitalism is shit.

What have we done to our young people..? Back when I was their age, we worried about Nuclear weapons. We knew we had bombs and we knew the Soviets had bombs. We knew we each had a button, and if the button got pressed, there would be a big flash and that would be it. I was never told that nuclear weapons were my fault, and it was my personal responsibility, that I just had to change my lifestyle, and try hard to get everyone else to do so, otherwise we were all going to die.

We’ve got millions of kids who are so frightened, they think they wont get a chance to grow up. Many young couples deciding not to have kids so we don’t have the patter of their tiny carbon footprints. It is absolute evil. What on earth have we done to our kids to appease the junk science of climate hysteria.?

The animal rights activists have been around long before social media or Amazon. T

They have had their uses, ie, in reducing animal cruelty and improving welfare.

But their intention to impose a vegan diet on all of us, who are omnivores, not herbivores, is completely unacceptable.

if they don’t want to eat meat, fine. No one’s forcing them, but perhaps someone should point out just how dreadfully undernourished a majority of the population was back around the time of WW1. There was a lack of good quality protein and essential vitamins in people’s diet. This wasn’t acknowledged until so many men tried to volunteer for tge military in WW1.

And if they expect people to have enough plant food to eat, it can’t be “rewilded.” Much of the land used for animal grazing isnt suitable for crop growing. Where do they think we’ll be getting fertiliser to grow crops from?

Send them to Sri Lanka to see how things are working out there.

Come on. There were plenty of wanky wonky protests in our day. That smelly cretin who lived up a tree. The camps of CND protesters around Faslane (I had to deal with those useless eaters and boy, were they smelly or what!) with their green haired brats who hadn’t seen a bath in years.

The Vietnam hippy protestors (they had a point but shunned returning Vets) which spread to the UK for some unknown reason as we weren’t fighting there and it had nothing to do with us.

The twat John Lennon and his dippy dame Yoko having a lie in to protest war. Lovely when you can spend the day in bed in your luxury hotel objecting to people fighting for your right to afford it.

Loads of them, but few of us bothered with the news then, we just got pissed and chased birds.

Perhaps that’s the easy way out in my old age. Hmmmmmm…….The old dears are a bit scraggy now though.

They had Woodstock festival beck then in a supposed pandemic.

Indeed, the original protestival.

Every performer had to have a protest song, about something.

Canned Heat’s ‘On The Road Again’ was a complaint about potholes? I shall view it in a new light from now on.

I always wondered how they got to keep those ‘green-haired brats’ away from school. Surely, nobody thought the kids were getting home schooling?

I don’t suppose you are exactly luscious yourself!

Didn’t say I was.

so the vietnam war was about fighting for my rights?

really?

i have always thought it was about making some people an insane lot of money, like all wars the usa have been involved in.

I’d suggest that ‘we’ve’ done very little to the children. The hysteria has come almost entirely from MSM and what used to be the education system, before it morphed into doling out unashamed propaganda.

“Incredibly two of the protesters – who were from Animal Rebellion – were able to sit in the middle of the Mall as the marching band approached.”

Might we surmise that the police were caught in a temporary dilemma while they tried to work out whether the protesters were of the type that they were supposed to whack with batons and roughhouse into the nearest Black Maria, or of the type that they were supposed to join in and boogie on down with? Were they waiting for instructions from the Home Office accordingly?

“By the left, quick march!”

“LEFT WHEEL!”

“March over any trash in the way lads!”

I mean, it’s utterly hilarious. The green blob invade a parade of people who are amongst the most lethal fighting force on the planet, and expect to make a point.

The armed forces are sworn to defend their nation and their Monarch. The cops did the protestors a favour by getting them out the way of an emotionally charged fighting force carrying real guns with really sharp bayonets on them.

Close call folks. Really bright cabbage munchers.

Nah – these were for decoration only. Wouldn’t want to mess up all that brass and bearskin, especially after they’d spent so much time practising.

Any organisation making threats such as those by Animal Rebellion should be declared a terror group and have their funds sequestered. Protestors frightening animals can cause miscarriages and deaths of animals. Farmers should be granted to use lethal force against such trespassers on their land.

The crowds turning out for the Queen today show that millions of people are being held hostage by a few thousand weirdos who have infiltrated key positions in government, the state, business and education. Put simply, there are tens of millions more of us than of them.

“…millions of people are being held hostage by a few thousand weirdos who have infiltrated key positions in government, the state, business and education. Put simply, there are tens of millions more of us than of them.”

Yes… and all those ten’s of millions more of us worked really well saying no to the nonsensical, economically, physically and mentally damaging non medical covid prevention measures didn’t it?

Indeed: if anything, they’ll have been encouraged by the mass compliance.

The nation elected a Prime minister dedicated wholly to carbon zero and all the ruination entailed. Johnson’s executive supposedly preside over the department of education where kids such as the above are taught. Wound up to believe in the great green myth. Rewilding, veganism, have these children no sense of the world, hard economics the reality of going vegan and, evidently not. But then animal rebellion or xr, whatever handle they give themselves on the day and in their fatuous beliefs, at its stem, who set them to tick in the first place, if not hmg?

Maybe hmg but no longer “our” government.

None of this on the BBC (so far as I can see).

I’m sure my wife would have told me.

Get away!

Spare billions of animals? What do they think will happen to the dairy herds if they manage to shut them down? Do they expect them to be let loose in the fields?

The last ‘wild’ herd of cattle in the UK lives in Chillingham, Northumbria. A marvellous white breed. Beautiful animals. But with the lack of natural predators, the herd has to be managed and culled as part of the process of preserving it.

These insane protestors are utterly detached from how the world works.

The single best thing that can happen to any animal is to be domesticated by man (I exclude factory farming in this).

No wild animal, in its natural state, dies painlessly or of old age. They starve to death, they are eaten alive by predators, they freeze to death in winter. These idiots are totally divorced from reality – living in a child’s fantasy of fluffy wickle animals who just want to be free and live together in a forest glade.

They need beating into adulthood.

Yes, I’m not sure that banning fox hunting did foxes any favours (let alone farmers).

Were fox hunting not celebrated by an almost religious display of wealth, I would agree.

How about the farmers are just encouraged to shoot foxes that bother them rather than sending 20 horses and 50 dogs to run down a single fox?

They are welcome to their blood sport as far as I’m concerned, but it can’t be justified as necessary.

Some traditional foxhunts are on foot I believe.

Still opposed by the class warriors obvs, can’t have working class countrymen engaging in predator control!

On foot, without a pack of hounds is fair enough.

From personal experience of our local farmer, who was good enough to employ me every summer when I was a kid, that was his tactic.

Take a long walk with a shotgun and despatch every fox he saw as humanely as possible. Or ambush them.

If there’s anyone on the planet who cares for animals more than farmers, I have yet to find them, and it’s certainly not the green nutters.

“If there’s anyone on the planet who cares for animals more than farmers, I have yet to find them, and it’s certainly not the green nutters.”

100%.

And I work with farmers.

That’s why the foxes moved into towns. More food, less fox hunting except by cars…

And the Seagulls moved inland after they stopped burning Landfill in the 1950s.

The urban fox dozing in my garden last week declined to comment.

You’re not the lefty BBC who love the wittle foxywoxies.

And effectively you can only spare one generation.

‘Activism is a way for useless people to feel important, even if the consequences of their activism are counterproductive for those they claim to be helping and damaging to the fabric of society as a whole.’ – Thomas Sowell

How do you define activism?

The parents who took the Welsh government to court over compulsory sexuality lessons for three year olds are activists, are they not?

My feeling is that if you are fighting to impose radicalism on society then you are an activist. If you are fighting to resist radicalism, then you’re not an activist.

Ah but who defines what is radical? And do radical policies eventually cease to be regarded as radical when they have been in force for a long period of time?

The first is not insurmountable, I think, but the latter is a fundamental and tricky issue for conservatives

Communism’s fairly radical, and remains radical for whatever period it’s in effect.

Isn’t it?

It is extreme and fundamentally nonsensical (the only people who can become wealthy are criminals and people who game the system (didn’t Arthur Scargill have a rather nice house?)).

And a Jag. All paid for by men who spent 8+ hours a day underground in hazardous conditions.

Not that communism is at all clever, the most simplistic, unimaginative and juvenile concept.

Indeed, is it possibly the single biggest contradiction of Occam’s razor.

Not sure what you mean there. Is it the single biggest contradiction of William of Ockhams razor (I live 10 miles away)?

Occam’s razor. The principle of parsimony which, without wanting to over simplify it, presents that the simplest solution is usually the best solution.

Communism, being the astonishing over simplification of society, that all men are equal in labour is the perfect solution for all mankind’s woe’s.

That’s the irony of Occam’s razor.

Despite being proven to cause woe’s people had never even considered, including Mao ordering all sparrows to be killed in order to stop grain theft.

Mao caused the grain shortage but in the usual manner of socialism, he blamed the sparrows.

But it was a simple solution. Personally, I would present it as the solution of a simpleton, but I might be accused of trifling with the English language.

Love to uptick, but thats such a reduction of communism. I would say the opposite, that communism proves occams razor. An aloof and apart bureaucracy has complicated the system needlessly.

I’m not comparing it to the reality of communism, rather the ‘philosophy’ of the movement.

Very easy to explain to the gullible – “equality for all, honey and roses” but impossible to implement in reality.

I get what you’re saying, and it’s absolutely correct, but persuading university students with the glorious simplicity and ‘beauty’ of harmonious life under a regime that “get’s paid exactly the same as you do” isn’t difficult.

Then the have kids, and everything changes. Well, for the clever ones.

Possibly why those early Trots were so beardie?

Am I an activist for opposing government overreach on things like covid and climate change?

Not by my definition, no.

LOL, thought not.

Bloody hell, let’s not sink to their level.

No, they’re passivists: They don’t want to introduce something, just not suffer something.

That’s an accurate coinage, but it’s not exactly inspirational!

I’d call them sensible people reasserting their rights to not have their children sexually groomed and/or being given inappropriate school lesson material by socialist pervs.

I’d have said they were more ‘parents’, since you ask.

It seems to me there’s a world of difference between protesting about something you know is happening and protesting about something you believe is happening.

Exactly so. And in an age where narcissism can now be monetized through social media, claiming victimhood and injustice, and displaying that through public activism, can now be a smart career move.

If you thing these Animal Extinction people are nutters, I advise you to stay away from the appalling swamp of social media, which is essentially a place for people with personality disorders to show off to one another.

This group say we should be re-wilding farmland…er…how are we going to grow all those lovely crops which will be so desperately needed? Also,they say we could save millions of animal lives if we stop eating them (implied, not actually put like that). If we stop eating livestock millions of them will be killed because they will have no purpose. These people are so stupid they seem to think farmers will retire their meat animals out to grass for idiotic vegans to coo over. What planet are they on?

I would have thought now we should be doing everything we can to get as much land as possible under cultivation to improve our self sufficiency as a country for this winter. Hard times are coming.

The Welsh government is buying up farmland in order to plant trees!

Yes, but the Welsh Assembly have often proved how useless they are. In that regard, they never fail to disappoint!

Yummy, Bark for dinner!

Acorns are turned to in times of famine…

(If you’ve ever tasted them, you’ll understand why that is the only time!).

Woof!

Round here we’d have to eat the squirrels first. They defend the acorns pretty viciously.

Squirrels are very tasty.

I’ll guarantee they’re tastier than those acorns…

Dig for victory!

Monoculture and GM foods are our enemies, not decent farmers who know how to get the best from their land – naturally.

Rewilding (not economically beneficial as food becomes scarcer, so not pursued with any ecological goals) would simply mean that pasture becomes scrub, and then tangled woodland. A huge blow against biodiversity, and all the non-forest species die out.

Alternatively, can we imagine how to preserve ancient meadows without grazing, and without using fossil fuels. Who is going to pay the man with the scythe?

In Norfolk and Suffolk, after prices collapsed after the First World War, a lot of farmers went bust and got out. Meanwhile, the farmlands, as we say here, “went back”, with overgrown hedges and fallow land. The next War, and the need to feed an embattled nation, revived agriculture. Then, joining the Common Market changed it again, but not for the best, as far as food security and self-sufficiency are concerned.

Part of the modern day farming problem is competition from imported goods like avocado’s and bananas, for example.

We have a fairly cruddy climate to grow much more than root crops and grains in the UK. It’s not that people don’t eat them, they just naturally eat less of them because they are eating more exotic fare.

Whilst the green blob bleats (ironic term) about being vegan/vegetarian etc. they can enjoy that whilst indulging in their favourite papaya or Passion fruit. But when all but essential flights are stopped, they will have to chow down on boiled turnips and cabbage, as a treat.

Their favourite vegan chocolate will also disappear, as will all chocolate because, of course, we can’t grow the necessary beans here. Coffee and tea will similarly be off the menu.

We can do warm Bitter though.

I like rewilding. Genuinely, I think it’s a great idea to introduce formerly native animals back into the wilds of the UK.

Packs of Wolves roaming the highlands of Scotland really appeal to me.

We can then genuinely offer the green blob the opportunity to live as they want the rest of us to live.

Mind you, they would require a settling in period, the first time they gut a rabbit they would vomit, as they stink. Big game is even worse. But they would learn the value of cooking and eating offal.

They might insist they stick to their vegan diet. Good luck with that, you can’t grow fields of tatties and lettuce for long in Scotland. They either get consumed by ravenous slugs or destroyed by an early frost. So it’s catching and cooking game and fish or……well, nothing really.

And once they have chopped down the trees, there isn’t much available to burn to cook with and heat their homes.

The only problem left for them is that they’ll be competing with the Wolves for food, and Wolves are far better adapted to killing and eating things with four legs than they are.

Anything on two legs is asking for trouble.

The ecozealots are also blissfully unaware that large parts of upland UK esp Yorkshire, Northumberland, Scottish borders & Highlands, N Wales etc are completely useless for crops.

Even fecking grass struggles, so the only food we can raise on most of it is sheep.

Don’t say anything or you’ll encourage the windfarm brigade.

Another bunch of nutjobs.

Nearly as nutty as the windrush brigade

Correct , but as someone who lives on those uplands and who works with the farmers looking after these acres I can tell you they do an incredible job.

Re-wilding is firkin nonsense, it really means losing the land.

Now we’re talking.

Or typing at least.

I seem to remember an idea to reintroduce the lynx to Kielder forest. I don’t think it went down too well with some of the locals…

And in France or somewhere, the wolf had some implacable enemies.

I hope things won’t get to the point where the public seeks these nutters out personally as the identities are probably not a big secret.

Both sadly and fortunately, conservatives are largely opposed to violence.

Forget Poxymonkey; EcoCretinism is rampaging through the country. If in doubt, I say “Eat Your Greens”.

How to win friends and influence people.

Mind you, we notice the police were an awful lot quicker to carry the nutters out the sight of HM and jug ears Chump Charlie (who loves them) than they have ever been to unglue their faces from the M25 – with a swift pull.

I’m actually very proud of those demonstrators today. They really are a bunch of Committed United New-world Truthseeking Soldiers.

Crazy unwashed nonwashed theatrical students

I do hope you post this again.

I have had a sherbet or two and won’t remember this tomorrow.

Whenever we’re refering to ER, or one of their offshoots, they shoud be refered to as:

“The Astroturfing Protest organisation Extinction Rebellion” or an offshoot thereof.

Edit: sorry, replied to wrong post.

Oh, not “Elizabeth Regina”?!

Anyone else notice the smug Guardian reader with his mask over one ear applauding in the background of the article photo? And I assume his equally sanctimonious wife in front of him.

LOL. Missed it, but now pissing myself.

I’m absolutely certain this human specimen will consider being carried to jail in front of a baying mob of cynics as a badge of honour.

No doubt she will be deprived of the comfort of her suburban detached house, the company of her two children, and the pleasure of her Labrador.

Meanwhile her ever suffering lawyer husband will be forced to travel across London in his Mercedes SUV to collect her from custody, because getting the bus back and enduring the company of Hoi Polloi is, “quite simply, far too distasteful dhaling”.

She will doubtless display the shot, framed, prominent in her modest hallway for her humble dining guests to worship as they assemble for cocktails, before the roaring, environmentally friendly log burner, in her faux Tudor open hearth fireplace. It’s all she can afford.

“Don’t worry though”, she calmly assures her guests “Our sacrifice is worth it, we have installed a £30,000 Heat Pump, £20,000 of solar panels and £10,000 of battery back up, plus an emergency diesel generator so the government announced blackouts won’t affect us this winter; and of course you are all welcome as you are surely too poor to do the same. Assuming we haven’t filled the house with Ukrainian refugees of course.”

“Which reminds me dear, did you order that large safe from Amazon. You know, the one big enough to fit my jewellery, Gucci wardrobe and the children?”

At her next green meeting she will display the photo declaring “no, no, dhalings ~affected simpering giggle~ the crowd were baying at the wicked police officers for arresting me. I could clearly hear them chanting ‘Let’s Go Brandon'”.

~Attenborough commentary kicks in~ It’s a busy time for the downtrodden protestors. Summer approaches rapidly, and their perennial blossoming to occupy London streets in fine weather is upon them. It will be short lived though, and they must gather sufficient virtuous sustenance to see them through the long, hard winter. These oppressed souls carry the nations social burden. ~David fades out through gentle, somber sound track~

Damn climate change, look how it’s changed us all!

Let them eat acorns (no seriously, they’re horrible)!

The protestors are indeed horrible.

The same way Covidianism has brought together people from the far right to the far left, in our resistance to absurd ideas and rules, veganism can be expressed together with the specter of climate change or it can be just an expression of compassion to non-human animals. Most of animal agriculture is extremely cruel to animals, from conception (as in the so-called “rape racks” of cows) to confinement into very tight, filthy quarters (we think our lockdowns were bad…), to the horror of live exports, etc. If we like questioning, let’s question everything, including the animal agriculture status quo, and look for alternatives.

Come again?

I bet they get their funding from Russia.

Oh like Arthur Scargill…

Nah, demonic Vlad wasn’t around then.

Besides, Vlad only funds wealthy blokes like Trump, who doesn’t need his money.

A mere detail, I know.

Now, don’t spoil it.

There is a time and place, this was neither. Ever since Emily Davison threw herself under that horse every protestor has thought they could be just as famous & successful. Without dying of course. But there is a vast difference between getting the right to vote and express your choice at the ballot box and these environmental protestors. They were lucky they weren’t hurt worse by accident .

She didn’t throw herself under the horse – that’s a constructed myth. She was trying to cross the track to hand out leaflets and got her timing a bit wrong.

Daft bint then.

This is perhaps a terrible admission but I’ll make it.

As an ex cop, were I one of those cops carrying that woman, I would have feigned stumbling, and walking as slowly as possible, as close to the public as possible, in the hope that someone had even a cheese and tomato sandwich to rub in her face. Perhaps even a bottle of water to squirt at her and, heaven forbid, a punch to emerge from the crown directed at her.

I wouldn’t have positioned myself between her and the crowd, rather, I would have ensured she was as close to them as possible.

Stumbling under her weight might have meant she clouted her head against the railings – “what else could I do Guv, she weighed a ton?”

I might even have dropped her once or twice. “I lost my footing Guv, what can I say but sorry”.

There is nothing in this world quite as satisfying as chasing down and tackling a guy to the ground who has stolen an old dear’s purse. Forget your paedophile convictions, rape convictions, robbery convictions, they all take years of drudge (as satisfying as they are on conclusion) catching someone in the act is the best feeling in the world.

I have chased neds through tenements, gardens, over hedges and fences, along roads, over railways, up tower blocks (easy, dead end), through industrial estates, pubs, clubs and dwellings. I have been left utterly breathless after miles of running, but I damn well didn’t stop. That ultimate satisfaction of catching the bastard was just too much to resist.

Dealing with these morons like the bitch in this photograph, is sincerely, depressing.

If there’s anything you can admire about a ned, it’s his bravado, fierce independence, and misplaced courage.

These people have nothing. No courage, no resistance, no conviction, no need to steal to feed their family or even their drug habit. Nothing but an incantation drummed into them about their virtue and right to command others.

Cops do what everyone else wants to do to criminals, catch them and despatch them (metaphorically), although not brutalise them. Then the virtue kicks in, and suddenly cops are the villains.

A BLT or Pastrami sandwich would be likely to have a much more devastating effect.

Sadist!

Cost? We must set our priorities.

Talk about I wish.

Thanks Red.

I can comment from the other side of the fence, there’s nothing quite as satisfying as clouting a pig hard!

Incidentally, were there any groups at that time campaigning for working class men to vote? We never seem to hear about them.

Queen treated like royalty shocker!

(Actually they all are if that summit in Cornwall was anything to go by…).

One day of cuntery over, another three to go

You not enjoying the platty jubes then, hun?

Is it not customary that some horses have a dump during these parades?

Rub the faces of those arrested in the shit – they need to be fully aware of what they are dealing with.

Thats what I’d love to do to dog owners who let their noisy pests foul the pavements

“This transition is common sense and simple, we all win. Seventy-six per cent of currently farmed land could be re-wilded…”

Great idea – we all starve to death. These are the same people who think the Great Reset is intended to reduce the world’s population – yet their methods are guaranteed to end in mass starvation.

Another Globalist funded group I suspect.

Headline should read morons turn on other morons!!

25 protesters? That’s a single ant on a large Oak Move on, nothing to see here.

Instant reaction from the police was good to see. Hope to witness more of the same against them and eco lunatics in the future.

If only those protestors had spent the day defacing or toppling statues, the police would have left them alone (or offered to make them tea)…

Could I suggest that Beau King Houston’s name is rather more complicated than his thought processes?

Beau King Houston, a name you often hear across the classroom in the local comprehensive, or called by his mum to come in for his plant based tea in deprived areas across Britain,

“Seventy-six per cent of currently farmed land could be re-wilded “!!!

What are we going to eat? These lunatics need to be locked up for a very long time.

Animal rebellion? Too bad they fighting for their own lives. Mandatory vaxxes in order to work, attend school, live. Perhaps these well funded rebels might put their efforts into getting a job, facing reality. Cows are hardly the enemy guys.

Time the police used their batons on these middle class morons

BTW, Ballard predicted Extinction Rebellion way back- read his “Millennium People” about middle class “terrorists”.

There’s no need for violence. Just make them comply strictly with the lifestyles they’re advocating – they need to fully audit themselves and eliminate anything that has an adverse impact on whatever they’re protesting against. Same goes for the climate change protestors. They’ll basically have to live outside and eat nothing they haven’t grown themselves. See how long it takes them to abandon the nonsense, they might last till it gets a bit cold but no longer.

How strange …. Plod can immediately haul these extremists out of the way when it involves the Queen in some way, but when it’s millions of motorists held up on the M25 or prevented from travelling to their jobs in London, they seem to be untouchable.

You got there just ahead of me.

Why can’t the ib/xr scum be lifted as soon as they block a road?

We had a barbeque yesterday evening ….. as we ate chilli pork skewers, marinated chicken, minted lamb steaks and bratwurst we stuck two fingers up to the Vegan Extremists who think they have the right to dictate to the rest of us what we should eat.

Custodial sentence required – these people are seriously dangerous and up until now have been actively encouraged by the benign inaction of the Authorities .

More to the point, they know absolutely nothing about animals as most live in comfortable featherbedded, wealthy suburban environments and never even visit the countryside.

They are yet more evidence of our increasingly sick society, detached from any physical reality or contact with reality outside the infantile fantasy simulcra of the digital paradise they inhabit..

We should re-introduce the stocks in town and village squares; items like rotten fruit and veg could be purchased for a few pence, the proceeds to go to animal charities.

Don’t these idiots realise that if we go down their route the only place we’d see these animals would be at the zoo? The beautiful British countryside would be bare and silent, because nobody is going to breed these animals if there is no living from it. Or if they were turned out into the wild they’d be attacked and eaten by wild animals?

What we should be doing is hugely encouraging humane, free-range farming and stopping the transportation of cattle and sheep (done so that the French can kill the sheep in France and claim it is French lamb). Also, to outlaw the barbaric practice of halal and kosher slaughter (but nobody has the guts to do that).

These fools are puppets of the globalists and their ‘great reset’, who, when they’ve reduced the peoples’ diet to veganism, will have their own private herds to enrich their own diets with plenty of meat.

They should all be rounded up into a market square, branded with a bright colour and then let the public at them to give them a damn good pasting

What a quick and decisive response!! The Transphobic & Racialist establishment must hold their heads in shame… After all it’s a terribly important cause so why they couldn’t just let them glue themselves to the road, lie down for several hours and block all souls from going about their business I can not imagine….. Oh wait, we mustn’t spoil the day, and the eye’s of the world we’re on us…. Ho Hum, yet more unbiased and perfectly rational thinking.

‘“Animal Rebels disrupt the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee celebrations demanding that Royal Land is Reclaimed.’

The Royals should have their land assets stripped and their rights to the seabed revoked (they get £200 million each year for renting it to the wind farm corporates).

The modern Royals are just the left overs from their earlier mafia ancestors and deserve to have their ill gotten gains confiscated.

The land should be let to indigenous people as small/medium scale farms, the rents should go towards deporting all the unwanted dross the Tories/Labour have allowed to move here.

Should anyone be giving them the oxygen of publicity?

A fair summary of policing in the UK over the last couple of years….

i agree with the protesters.

we should rewild a lot of land.

in fact we should rewild so much land that there is not enough food to feed the entire population so some will have to starve.

and the first, and only to, literally, starve to death should be the protesters.

Just a shame the BIB aren’t so quick to remove them when they get in the way of the ordinary people