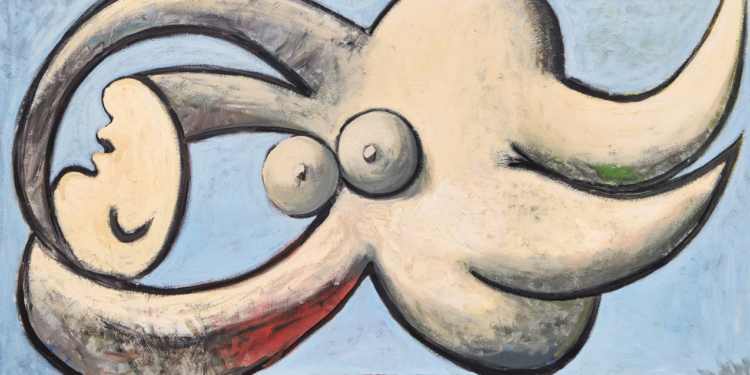

One sees, with great joy, that there is an exhibition in Brooklyn Museum, New York, entitled, ‘It’s Pablomatic’. The exhibition has been curated or directed by Hannah Gadsby, and, though she is reputedly a comedian, and though the title is flippant, the exhibition is intended to put a solemn question mark against the art of a misogynist. It opposes 50 of Picasso’s work to 49 feminist works, as if this is some great moral marble run. “Damn it, the Mademoiselles of Avignon came first again.”

I have almost nothing direct to say about this. The answer is in the question. The critique is in the content. The mockery is in the making. Satire is unnecessary because the entire enterprise is so subsumed in circular self-satire that it is even being offered to the public with a shrug, as if on a ‘Why not?’ basis. My first thought about it was that I hope that some other museum, perhaps the Metropolitan Museum of Art, will enable someone on the other side – the dark side – someone like Matt Walsh, say, to curate an exhibition considering the panoply of female and feminist art that runs from Lavinia Fortuna and Artemisia Gentileschi to Frieda Kahlo and Paula Rego.

The other thought I had was somewhat tangential but, I would argue, fundamental. I asked myself, ‘Why Hannah Gadsby?’ (I first heard of her, by the way, when accidentally listening to Matt Walsh trying to find her amusing.) Why did a Museum of Art in the United States ask an Australian comedian to edit an exhibition? One answer could be the Netflix Special. Another answer could be that just as we like to hear the reassuring tones of Jeremy Irons in Westminster Abbey, so we require that, on every occasion, there is a voice to suggest to us what attitude we should have – reverent or irreverent – to our environment. But there is another answer. I wondered if Hannah Gadsby’s name gave educated Americans pleasure because it reminded them, subliminally perhaps, of the Great Gatsby. By Gad, the Great Gadsby! Reborn in more acceptable form, now ticking diversity and inclusivity boxes.

This is where we arrive at the glorious science of names.

Hannah Gadsby. Hannah has a trustworthy Old Testament sound: that of a beloved but at first barren woman, later to be blessed by God. Gadsby is of course a crude Gatsby: Gatsby being an outsider, an arriviste, who achieves great fame through a sort of confidence trick. Great on the surface; not great underneath. Gatsby had a blue lawn; Gadsby has blue clothes and, spiritually, blue hair.

Once one starts, the science is an easy one to master.

Matt Walsh. Matt, oddly, is something that makes you welcome, and that you step on. It is also an attempt to hide the fact that the name is that of a biblical tax collector. Walsh signifies Welsh, which means foreigner: a word associated with weal. But there is a hint of ‘wash’, too: which explains the desire to clean up a dirty world.

Sometimes the name offers a contrast, or a secret. But sometimes the meaning is clear. Take the name of our Editor-in-Chief:

Toby Young. Young is young, of course. Toby is quintessentially English, eccentric and fond of jugs. There is a reminder of Sterne’s Tristram Shandy: a humorous take on everything which is remarkably persistent and eventually profound while never giving up the atmosphere of a shaggy dog story.

James Delingpole. James is, of course, a highly respectable name, and explains the respectable first half of a career. It is biblical, New Testament and ambiguous, since no one can count exactly how many Jameses there were, and which was which. One of the Jameses was the founder of the original Jerusalem church, and so there is a heavy tincture of the Old Testament about the name. (Also something of the shapeshifter: James is Jacob; and Jacob pretended to be Esau.) Delingpole, however, is as 18th-century as Toby: it is straight out of Fielding or Dickens. Hence the loquacity, irascibility, button-holing.

Nick Dixon. Short and almost rhyming, hence an affection of extreme simplicity. But there is a hint of danger, in the ‘Nick’ reminding us of Machiavelli (and Adam Sandler), and in the cocky surname. The surname is also shared by Jim Dixon, hapless and sentimental hero of Lucky Jim. Hence the name has an atmosphere of comedy and good luck.

Kingsley Amis. Amis suggests ‘aimless’, also misspelt ‘aims’, though it has a hint of strange elegance. Kingsley is an allusion to 19th-century literature, also suggesting what Bede used to call an ‘under-king’. A kingsley is not quite a king. If Kingsley had had any hopes for his son’s career as a writer he would not have called him Martin, a name for Protestants bedevilled by bodily difficulties, but something like Carroll or Blyton.

Will Self. This is name so spectacular that it is a shame Martin Amis did not think of it. (It makes John Self seem a bit amateurish.) As with Hannah Gadsby, the answer is in the question: ‘Will.’ ‘Self.’ QED.

Joe Biden. Biden is, of course, a reminiscence of ‘biding’ which refers to what the President is doing with his time, and also what the Democratic party and the United State are doing with their time. Joe is spectacularly ordinary, though it is meant to hide (this is the Bible again) a taste for power, having to put up with troublesome relatives and, unexpectedly, a fondness for wearing colourful clothing. Biden also suggests ‘bid’: cash transactions.

Theresa May. Theresa May but she may not. A fundamental suggestion of ambivalence.

Gordon Brown. Was doomed by the comparison with Tony Blair. Blair suggests ‘flair’ (as well as, famously, ‘liar’), and the initial ‘B’ of the surnames not only condemned Brown to association with Blair, it meant he came second – alphabetically, and also in colour. Flair leaves brown nowhere. Plus, Tony is not made in Scotland by girders: it is a slippery name, implying political ballet of a sort impossible to a Scottish tank. Tony, incidentally, is the name of the hero of Waugh’s novel A Handful of Dust, the theme of which was ‘It was nobody’s fault’.

Jordan Peterson. The first name is ambiguous: firstly, neither distinctively masculine or feminine; and secondly it is biblical (the name of a river) without being a biblical name as such. Hence ambivalence about the Bible: very much of it, but not in the usual way. The name Peterson has something of the cold, insane Strindbergian north about it – hence the atmosphere of Ibsen’s Brand which surrounds Peterson.

Ian Hislop. Ian is a sort of John: unworthy of unloosing someone else’s latchet (e.g. Peter Cook or Richard Ingrams). Hislop refers to ‘his lop’ or ‘lope’, a tendency to one-leggedly veer to the left.

Holly Willoughby. An excessively alveolarly laterally approximant name: too many Ls. Also too many trees: holly and willow, suggests prickles and withies, and a hint of whiplash.

Niall Ferguson. The name of someone determined to do anything not to be confused with Neil Ferguson. Niall also implying ‘nay’.

Jimmy Savile. Jimmy is a corrupted James. Savile implies fancy clothes (Savile Row) but also ‘vile’. Vileness hidden behind an appearance of being a saviour. A perfect name for a DJ turned BBC salvation figure turned posthumous reprobate.

Rolf Harris. Rolf is reminiscent of ‘wolf’: of course slightly obscure. Harris refers to tweed, that is, wool. Hence a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

Meghan Markle. There is more than a hint of Dickens about this name. The surname is almost comical, but suggests trying to make a concern with making money (‘mark’) in a sparkly Hollywood manner. Meghan has an ‘egg’ and ‘hen’ element to it. Alliteration is always significant: has the effect of making the name comical and possibly sinister. A perfect accompaniment for ‘Harry’: the name of the most open and affable sort of man, especially if one drops one’s HRHs.

Penny Mordaunt. Another remarkable name, also somewhat Dickensian, suggesting, again, money, but also mordancy with a hint of medieval elegance. Also there is the distinctive Dickensian touch of ‘mord’ (Murdstone, Merdle etc.). Penny is cute (and cheap), trying to be small; but penny farthings were colossal. The surname was suited for someone carrying a sword.

Liz Truss. An overly sibilant name. Truss is, alas, also Dickensian: it suggests being tied up like a chicken. Since this is what the Establishment did in 2022, again we have evidence that name is destiny.

Rishi Sunak. When names drift too far away from English names there is more speculation than science. ‘Ready for Rishi’ and ‘Dishy Rishi’ have been attempts to domesticate his name. Rishi suggests Rikki-Tikki-Tavi and Reepicheep: valiant rodents. Sunak has to be analysed in the same way Kingsley Amis analysed Iris Murdoch’s name: ‘Aye! Merde! Och!’ ‘Soon’ certainly suggests a useful political anticipation of the good to come.

Keir Starmer. He should have been the lead guitarist of Ugly Rumours with a name like this. Keir suggests, not ‘queer’, but certainly a bit unsure about how to define a woman. Starmer is a cross between ‘star’ and ‘murmur’, a very odd combination.

Elon Musk. Those on the left hold him in bad odour.

Lord Frost. A good name for someone warning us of the folly of changing our energy policy. If we all install heat pumps our windows will be graced not by the elegant tracery of Jack Frost but the glacial icing of Lord Frost.

Nigel Farage. A composite name suggesting the conviviality of a minor knight or bookie, but also in ‘Far’ and ‘Age’ suggesting an eye for the grandest scale of all (cf. Faramir in Lord of the Rings.) The implied rhyme with ‘garage’ also lends the name the necessary atmosphere of second-hand car salesman.

Piers Morgan. A networker, apparently always building bridges, but actually acting for himself: the bridges go nowhere, are piers. Good for sun-tanned blow-harding. All this activity is, almost needless to say, for more gain.

Emmanuel Macron. A perfect name for a modern Napoleon. ‘Macron’ meaning big, but only a hair’s breadth from ‘micron’ meaning small. Gillray would have stuck Macron on a toasting fork and had him slicing up Europe with Merkel.

Owen Jones. Owen suggests ‘own’ (like ‘will’ in Will Self), but with a whining second syllable. Jones is short for cojones, suggesting Jones has balls; but those balls remain his owen. The entire name also has a hint of ‘own goal’, alluding to the self-defeating nature of the critique. We may note that the letter S is on the far right of his name. Perhaps he should rename himself Owen Jone and, as is essential, dissociate himself entirely from the far right.

Ash Sarkar. A remarkable name, aptly suggesting worthless sarcasm.

Lord Sumption. Another remarkable name, suggesting ‘sumptuous’, ‘gumption’ and ‘assumption’. Positively 18th-century in its tonality. Jonathan is sweet, but suggests Swift. Everything is bewhigged here and covered in snuff and very intelligent.

Pablo Picasso. I hope Gadsby saw the punning potential in the Kingsley Amisesque ‘Pick-Ass-Oh!’ She also could have made use of the fact that ‘pabulum’ is tasteless food or other matter.

Almost no one is safe from the science of names, scientia comica nomina. I leave the subject to the reader, with some hints. Anyone with the name Moore wants more than more. The ‘h’ in the name Whitty requires explanation. Vallance suggests ‘valiance’ but also ‘balance’, an odd contradictory combination. Gove is reminiscent of Hove, a small town always to be found nestled next to a larger town (does anyone remember Johnson and Gove Albion?). Fauci was obviously a tap pouring out nonsense. Greta Thunberg is not much ‘thun’ or fun, despite the fairy story first name: she creates enough moral effluent to block the London sewage system. George Monbiot has only one theme and, unexpectedly, it is to do with humanity as a threat to life.

May you all go on to apply the science of names to your colleagues and favourite public figures.

Dr. James Alexander is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at Bilkent University in Turkey.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Well this is doubly tragic but I’ll let you read it and draw your own conclusions;

”A two-month-old boy who was born prematurely after his mother suffered a fatal blood clot died in his sleep just weeks later, an inquest has heard.

Dexter Khan-Barnes was born at just 32 weeks after being delivered by emergency caesarean section when his mother, Laura Barnes, developed the clot.

At Wednesday’s hearing the court was told by Laura’s mother, Jennifer Barnes, that her daughter had suffered a stroke in the months prior to her death and the premature birth of Dexter.”

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-12171763/Baby-born-prematurely-blood-clot-killed-mother-tragically-died-just-two-months-later-sleep.html

So many tragic coincidences afflicting the one family.

Call me paranoid but I’m just thinking of all the pregnant women coerced and scared into getting jabbed, being lied to that they were at increased risk from a virus, and thinking, ”what are the odds?” It doesn’t mention her age but she looks very young in the picture. Young, healthy women don’t just have a stroke. Personally I think family has a duty now, a moral obligation, to declare publicly if their loved one had the jab or not. If they don’t I always think, ”why not? Why’s nobody mentioning this incredibly relevant detail?”. Think I’m getting too suspicious for my own good but I’m even wondering if they’re getting some sort of back-hander, a bribe, in order to silence them. After all, what would anyone have to lose by saying someone’s been vaxxed or not? They’ve already lost a beloved family member FFS?

Sadly Mogs I suspect our original and worst fears are playing out. Mothers are going to die young, babies are going to die very young, children won’t reach adulthood and young adults will find they are infertile. I am sad and angry but these types of events will inevitably become more common. It has all been planned for.

The artcle states that the child had been seen by a nurse at his home the day before he died. One can only speculate, but were the 8 week jabs administered during that visit? The baby was only just reaching the developmental status of a new born.

The grand-daughter of someone I know was born three months prematurely last year. The mother is a nurse and vaccinated as required including during the pregnancy. The baby was born with organs in the wrong place, organs adhering to each other, poorly functioning kidneys and brain damage. She’s had multiple operations with more to come and will never lead any kind of normal life. She was in hospital for the first 9 months of her life, home to a specially adapted environment for about 8 weeks and requiring 24 hours a day care then readmitted to hospital where she has been for months. It is desperately sad for all involved.

I believe it’s a result of the vaccinations the mother had but obviously can’t say that as being a nurse the mother did all the “right” things and vaccinations are believed to be a Good Thing. I contrast the vaccination of pregnant women with the fact that when I was pregnant I was expected NOT to touch even so much as a paracetamol. How times change…

You are quite right. It beggars belief that pregnant women are presumably still advised to avoid soft cheeses and pate but the mRNA novel, toxic junk is totally encouraged! Insanity. Your above story is absolutely tragic. 🙁 In my book nowadays, it is always the vax until proven otherwise.

One can only sympathise with both this poor child and its parents, but there is a word of warning to be added. Having studied embryology at University and seen the distressing range of bodily changes that can result to a foetus in utero (the worst resulting in spontaneous abortion), it is a constant amazement to me that a baby is born complete and whole.

I hope this was written by Chat GPT.

That’s funny, I enjoyed the article though.

Ah, Chat GPT – that upstart Frankophile moggy with GPS to strategically crap all over your brassicas, spinach and sanity.

Please don’t refer to Gadsby as “Australian”.

She/he/it/they is/are “Tasmanian”.

Tasmania is to Australia what Gadsby is to comedy.

Or, Tasmania is Australia’s scrotum.

(Strong sarcasm alert here regarding Tasmania, not Gadsby, for the literal minded down-tickers)

Nice one Dr G 👍

Theresa May

Ronnie Wood

Brian Cant

Immanuel Kant

Sadiq Khan

I expect Jeremy Irons to be always very neatly dressed.

I wonder about Lionel Messi’s kitchen.

The science of names is a fascinating, and probably under-researched, topic.

I think – like it or not – names affect how we think (subliminally) about a person, especially initially, probably for various reasons, not least because we associate the name of a person with someone we previously know with the same name. In my 20s I was in love with a beautiful girl called Anna, I never really fell out of love with her. Ever since, I have a prejudice in favour of anyone called Anna, I immediately like them more than if they were called, for example, Daphne or Liz. It may turn out that Daphne or Liz is a far more wonderful person that any of the Anna’s (apart from the first!) but that’s prejudice for you!

I write fiction, and it sometimes takes me longer to decide on the name of a character than to write pages of dialogue.

My friend and I find names which are commands amusing, especially footballers, as you can imagine their coach shouting instructions at them from the touchline. Just a few examples off the top of my head:

Peter Crouch

Terry Neill

Luke Young

Winston Reid

Ian Wright

In politics:

Jeremy Hunt

Mel Stride

and last but not least:

Donald Trump!

In the 1970s I knew a person from Derry whose real name was Donald Tuck (what were his parents thinking?) I was never with him when he was stopped by the British army, I can only imagine it!

I’ve found that midnight feasts do not agree with me and I suffer from hydrophobia due to previous horrific experiences with water.

A GP of my acquaintance is called William Willcock. His father was a vicar so the likely reactions to his son’s name probably passed him by?!!

“Elon Musk. Those on the left hold him in bad odour.”

Until about three years ago, it was very much the other way around. Socialist Kalifornian Politicians and People used to love him – and he them! – until they ran out of other people’s money to give him for crappy cars and all his other boondoggles.

Then, as if by magic, Elon began to court that other tribe, “the right”, where he found a willing audience for his sudden change of tune (unbeknownst to them).

The Subsidy Truffle Hound and Pretengineer, Mr Elon Reeve Musk. The guy is a genius, just not in the way most believe.

Well I enjoyed that, it was so entertaining. My only problem was prefixing Sunak as Rikki as it reminds me of the Rikki-Tik a place of much musical and other youthful enjoyment in Windsor and Sunak is about as far from that as possible.

Funny and clever. Brilliant!

‘The Foreign Office

London

6th April 1943

My Dear Reggie,

In these dark days man tends to look for little shafts of light that spill from Heaven.

My days are probably darker than yours, and I need, my God I do, all the light I can get.

But I am a decent fellow, and I do not want to be mean and selfish about what little brightness is shed upon me from time to time.

So I propose to share with you a tiny flash that has illuminated my sombre life and tell you that God has given me a new Turkish colleague whose card tells me that he is called Mustapha Kunt.

We all feel like that, Reggie, now and then, especially when Spring is upon us, but few of us would care to put it on our cards.

It takes a Turk to do that.

[Signed]

Sir Archibald Clerk Kerr,

H.M. Ambassador.’