Barely a week goes by without some new initiative being announced to ‘solve the NHS workforce crisis’. It has become the cause celebre de nos jours and will probably be a major bone of contention at the next General Election.

This week saw the announcement of the ‘medical apprenticeship’ scheme – a new idea to increase the number of doctors and widen access into the medical profession. In traditional fashion, the media splash generated instant hostile pushback from horrified commentators choosing to interpret the plan as permission for school leavers to undertake appendicectomies. Equally predictable was the tedious condemnation from the medical establishment – ever eager to protect its intellectual hegemony and maintain barriers to entry onto the medical register.

I should state up front that I quite like traditions. For example, it is the tradition of the Daily Sceptic to look deeper than the mainstream media – to investigate and analyse the reality behind headlines. We think that’s what attracts our readership – so here goes.

My first observation is that this is not a new idea. Medical students have walked the wards as porters, healthcare assistants and general orderlies for generations. In my day it was a useful way of becoming acquainted with the junior nurses – a highly enjoyable way of broadening one’s education.

It’s not even a new idea in the near term. Health Education England (HEE) announced the plan on their website nearly a year ago.

From my perspective at the other end of a medical career, there are many advantages to aspiring young doctors getting early exposure to the sharp end of clinical practice (notwithstanding proximity to charming nurses). For a start, it enables students to decide early on whether the practice of medicine is really what they want to do. If it isn’t, much better to find out quickly and transfer to another career. The reality of medicine does not suit every smart teenager with good grades in science A levels and a starry-eyed belief in the priest-like virtue of the healer. That’s one reason why we have so many disgruntled juniors – the hype is not concordant with reality.

Using such a scheme to widen access to medicine for established healthcare workers in other fields also has potential. Over the last 34 years I have worked alongside some outstanding specialist nurses and allied trades. Within their narrow scope of practice those talented and dedicated individuals are every bit as effective as doctors. If some of them wanted to gain a medical degree via an apprenticeship route they would undoubtedly be a massive asset to the nation.

So, let’s put the hysterical pearl-clutching to bed. If we want more doctors, we need to train them, and an apprenticeship scheme is not a bad way to achieve that goal.

Now for the problematic part – the detail. The devil is always in the detail.

We can start by looking at the HEE website and their arguments in favour of the scheme:

The apprenticeship has been introduced to make the profession more accessible, more diverse, and more representative of local communities so patients are treated by a medical workforce that reflects the diversity of local communities. The aim is to recruit students from varying backgrounds, who may have struggled to pursue a traditional medical degree education, so that future generations of students, and health professionals, more closely mirror the population that they serve.

Frankly, this kind of bullshittery brings me out in a rash – it’s precisely the line of thought that devalues and degrades an otherwise worthy idea. The implication behind this type of nonsensical statement is that anyone can become a doctor if they have the correct demographic characteristics required to fill a diversity quota. Unfortunately learning the trade demands rather more than that. Whichever route one takes, there is a non-negotiable need to spend long hours sitting on a hard chair in a quiet room, committing vast amounts of information to memory – then demonstrating you’ve memorised it and can process it properly via a rigorous examination process. There’s no getting around it – not everyone is capable or inclined to manage the intellectual demands needed to get a medical degree. If, as HEE confidently assert, the apprentices will achieve a medical degree within the same five-year period as at university, then they are going to have to work a good deal harder than their equivalents on the traditional pathway.

My concern about the implementation of an apprenticeship scheme is that standards of examination will be ‘relaxed’ in the interests of diversity and of pushing more students/apprentices through the scheme. If that turned out to be the case, we would not be training more doctors – merely handing out badges in the interests of tokenism and political imperatives to get the numbers up. The only professionals benefitting from this scenario would be malpractice lawyers.

HEE and their fellow travellers are quick to state that standards for apprenticeships will be exactly the same as for a doctor trained in a medical school. That may be the aspiration, but past experience with ‘medical educators’ leads me to be suspicious about assurances of this nature. The usual argument deployed is that there are vast areas of the medical curriculum that students ‘do not need to know’ – that bypassing a granular study of anatomy, physiology, pathology and pharmacology can be done without degradation of a practitioner’s effectiveness in the workplace. I’m sceptical.

The argument about knowledge requirement really leads to the core question: What constitutes a doctor? What are the essential differences between doctors, nurses, and other health professionals?

In my view, the differences lie in the breadth and depth of knowledge which underpins the acceptance of responsibility for decision-making. It may well be the case that in everyday practice, an individual doctor will not use specific bits of knowledge. It will be rare for a practitioner to be called on to recall the branches of the trigeminal nerve, or to discourse on the modes of actions of different diuretic drugs or the clinical presentations of the four common types of malaria parasite. But here’s the point – medical problems do not present in isolation, wrapped up neatly in boxes with the diagnosis on a sticker. Medicine is complex. Diseases present with odd symptoms. Multiple problems overlap and transgress anatomical and physiological boundaries. Having a breadth of knowledge and experience makes errors less likely – if you don’t know what you don’t know, then you will be practicing in blissful ignorance – an accident waiting to happen.

But let’s give HEE the benefit of the doubt and accept their assurance that educational standards will not be lowered for the apprenticeship scheme. Who will train the apprentices? Hospitals and universities already struggle to provide adequate teaching for medical students, as experienced clinicians come under more strain to manage the NHS backlog. High quality medical education requires lots of ‘bedside teaching’ – small groups of students gaining regular intense tuition in history taking, clinical examination and the diagnostic process under the tutelage of senior doctors with decades of experience. Where is that coming from in the brave new world of medical education?

From my personal standpoint, as I approach retirement from clinical practice, I could be tempted to help out with a bit of teaching if the terms and conditions were similar to 30 years ago – but of course, they are not. Having one’s every remark scrutinised for ‘micro aggressions’, ‘unconscious bias’ or other contrived thought crimes, makes the idea of teaching modern day medical students extremely unattractive – indeed, those are the reasons why I withdrew from teaching some years ago. I can’t see many of my cohort volunteering to assist in training the next generation, as many outstanding retired clinicians did when I was at medical school.

Concerns have been raised by colleagues that an apprenticeship degree could be considered a second rate-qualification compared to a formal medical school education. I think this worry is exaggerated. In the crucible of clinical medicine, meritocracy usually prevails. If an apprentice doctor meets the standard, no one will even ask or care how they obtained their degree. I’ve worked alongside colleagues from all over the world, across the full spectrum of ethnicity and orientation. The good ones rapidly gain the respect, trust and affection of their peers – the idle or incompetent are equally rapidly exposed.

In summary, I have absolutely no objection to an apprenticeship style training in medicine. Indeed, done properly, it could be highly advantageous. However, I’m deeply suspicious of the motive and intention behind the implementation of this plan, based on my experience of the type of people pushing it and their track record of destroying much of what was good about British medical training and education over the past two decades. When medicine becomes politicised, standards slip and patients suffer. Feel free to call me sceptical, but my expectation is that last week’s fanfare was a performative piece of PR fluffery, carefully orchestrated to pretend that the clever people in the NHS had discovered a magic wheeze to fix an insoluble workforce problem at a stroke. It doesn’t matter which way you slice it – learning to be a doctor is hard work and takes a long time. There are no short cuts.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Apprenticeship style training can work well in other industries. It’s quite a few years now since I retired, but I dealt with several apprentices under my management/training, and quite a few of them towards the end seemed to have made a wise choice financially, avoiding the debit that would arise the other way via a degree course these days. The other side of the coin is that the meritocratic structure is more challenging compared with a conventional degree. However their balance sheet could look a lot better than someone who has been at university for a few years.

“More closely mirror the population that they serve”

Doesn’t that require far fewer non-whites than are currently employed?

My GP practice has 8 GPs. 2 are Asian – but born and educated here, thank God – and one Eastern European, but the population they serve is at least 95% “White British”.

What of the ill educated, not-interested populations? How will they be represented – if they should be?

And so continues the long period of educational egalitarianism aka dumbing down (has anyone read the most recent book by Peter Hitchens?).

In fact medical school and doctor training have clearly been dumbed down especially since the European Working Time Directive meant ‘educationalists’ felt doctors could be trained during 9 to 5 hours. You have to be close to the system to know this, but it’s also clear that senior doctors (itself a term that has become devalued) just can’t cut it as much as their predecessors could. This can be potentially disastrous in craft skills type roles such as surgery where you can only (largely) train for the procedure by doing it.

This website has had very good analysis on the UK medical system – long may this continue!

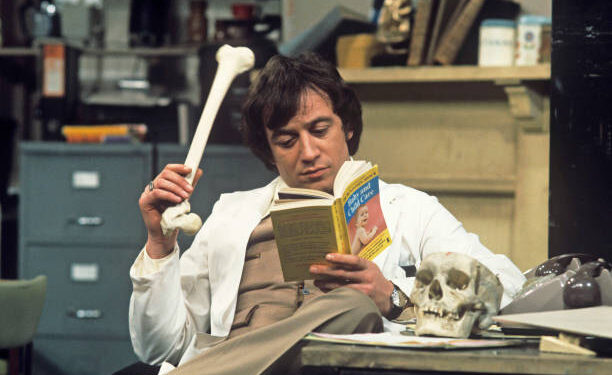

Thank you for the reasoned analysis (and the picture of one of my childhood crushes).

This nonsense was tried with nursing and has been a complete flop.

Everyone is complaining about nurses having to have degrees and not doing on the job training.

Indeed. I taught Access courses to wannabe nurses and the thought of some of them actually passing the course and being out there in wards and clinics is, quite frankly, terrifying!

Marvellous analysis. However Dr Anon is clearly younger than me; I qualified 50 years ago this month, and as a medical student did large numbers of unsupervised procedures such as stitching wounds in A&E and including a lumbar puncture when a student locum. As did all my fellow students. Just saying.

I agree largely with the gist of this article.

I graduated nearly 40 years ago in Australia.

I am not sure how Medical courses differ in the UK, but my training was a combination of imbibing knowledge (anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, pathology, etc) AND an apprenticeship style of learning practical skills.

There is no way to master performing a knee replacement other than to observe, assist, perform with help, then perform alone. This is, in essence, an apprenticeship.

This applies for all practical skills, but must come on a background of sound knowledge of the basics.

I agree that once the epithet “diverse” rears its ugly head, I can see only danger ahead.

Don’t they combine practical skills and. classroom learning currently? My daughter’s in the middle of doing a midwifery degree and she seems to spend her time between the two, or is it different for student doctors?

I understand the need to stay anonymous, as described in this very useful item by somebody who knows what they are talking about. I know nothing much about medical training, apart from occasional discussions with youngish people in training to become a doctor. As a result of that, I understand how hard it is and the commitment required to progress. The thing that seems difficult is that the same initial training is required for people who go on to the extra training to specialize and become, for example, a surgeon or one of the other top end specialisations. I just wonder if there could be a level of medical education suitable for say a GP that provided a good level of general medical competence that could be provided by the apprenticeship scheme suggested. Most GP’s main knowledge required seems to me to be when to refer a patient to a specialist, and one of the issues slowing treatment seems to be the lack of numbers of the specialists. If the upper competence group of training doctors could be faster tracked through their chosen specialisation, perhaps this would help increase the numbers of them.

I taught Access courses to wannabe nurses, doctors, dentists, vets etc. The requirements for entry to the course were decreased year on year so we got all sorts. The curriculum was dumbed down, the exams could more or less be sat repeatedly until they were passed and a lot of of the students were only interested in what they need to know to pass the exams, nothing outside the curriculum but with relevance held no interest. Some of the ones who went on to further studies were never going to make the grade but TPTB had made the decision and that was that. The students are “supported” through their course and a whole new world of support and counselling has opened up job opportunities in both FE and HE.

Interestingly our new neighbour (in her early 60s and trained on the wards) is involved in assessing final year nurses in the ward environment and is full of despair about the standard of training and competence. She’ll probably retire soon.

The writer of this article has made some excellent points especially about the breadth/ depth of knowledge required to joins the dots when required. The nuances of diagnosis are very important.