To lockdown sceptics’ great chagrin, recent polls have found that the majority of Brits are still very much pro-lockdown. In a YouGov poll taken in early March, only 19% of respondents said the government’s handling of pandemic was “too strict”, and a remarkable 37% said it was “not strict enough”.

Likewise, when UnHerd asked Brits whether “in retrospect, lockdown was a mistake”, they found there wasn’t a single constituency in the country where a majority agreed. Overall agreement was 27% – which is barely more encouraging than YouGov’s finding.

Now, you can always quibble with polls – the figures might be off by five or ten percentage points. But this clearly isn’t enough to turn 27% into a majority. So what explains Brits’ continued support for a policy that imposed such huge costs while conferring such small benefits (if any)?

Are many of us suffering from Stockholm syndrome? (although it should really be called ‘Wuhan syndrome’). Here are the factors I think are involved.

First: as veteran-lockdown sceptic Lord Hannan has noted with regret, “many of my countrymen couldn’t give two hoots about liberty”. Like the citizens of most Western countries, Brits have long favoured higher taxes and nationalisation of industry. So their support for lockdown isn’t exactly a major anomaly that needs to be explained.

Second: as I noted in my reply to Lord Hannan, Brits massively overestimated the risks of Covid, particularly the risks to the young. This owes partly to general biases in the estimation of small quantities. But it also stems from the intentional use of fear tactics whose very aim was to increase compliance with lockdown.

Third: the theoretical case for ‘flattening the curve’ was strong. If infections rise too high, hospitals will become overwhelmed, leading to huge numbers of deaths; a temporary lockdown can prevent this from happening. The argument is flawed, of course – not least because it ignores the ‘costs’ side of the equation. But it seems quite compelling.

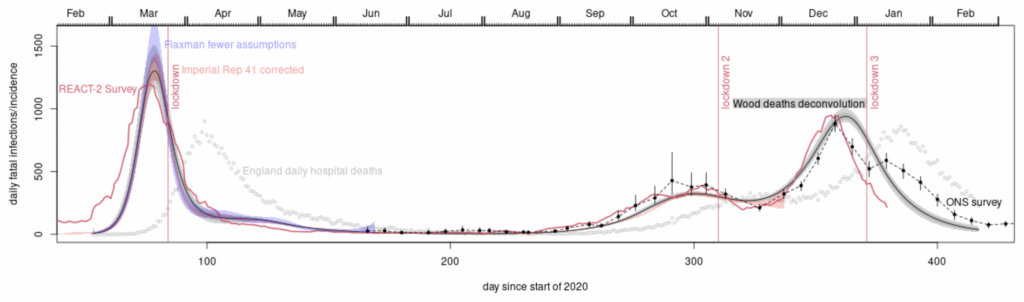

Fourth: case numbers did start falling around the time of each lockdown in 2020. Yet as the statistician Simon Wood has shown, infections were already in decline before the lockdown was called – in all three cases. This can be seen in the chart below, which shows the timing of lockdowns in relation to five reconstructions of infection numbers.

Fifth: while the supposed benefits of lockdown were obvious and immediate, the costs were largely delayed. As a result, members of the public are more likely to credit lockdown for its ‘successes’ than they are to blame lockdown for its failures – including debt, inflation and plunging test scores.

Sixth: for months, credentialed scientists appeared before the television cameras and informed the public that lockdown was the right choice – that the Government really was ‘following the science’. Meanwhile, dissenting scientists (like those who signed the Great Barrington Declaration) were consistently marginalised.

This last point is particularly important, as surveys show that scientists are among the most trusted professionals in the country. Through a combination of groupthink, deplatforming and biased media coverage, the public became convinced that there was such a thing as ‘the science’ and that it supported lockdown.

Three years later, they haven’t changed their minds.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

“When I was sixteen, I went to work for a newspaper in Hong Kong. It was a rag, but the editor taught me one important lesson. The key to a great story is not who, or what, or when, but why.“

I must admit it’s not entirely clear to me why it matters what gun was used.

Cover, Major, cover.

L Rons Hubbard is the usual apologist here for the US takeover of the Ukraine, its money laundering, bio-labs, its proxy war to try and weaken Russia, its imperialism.

Looking forward to L Rons next whingefest on the same, given that Russia has handed his deified NATO its ass.

I read somewhere that it was a regular 9mm poodleshooter reasonably expertly handled (dealt competently with a cycling problem).

The curious thing is the writing on the shell cases presumably designed to give a clue as to the why.

Health care is shall we say a contentious issue in the usa and the middle classes get well shafted by a deeply corrupt and unfair system riddled with government intervention (but I repeat myself).

A thoroughly sad story all round.

This appears to be some part of the motive:

‘A report released Oct. 17 by the Senate Homeland Security Committee’s investigative subcommittee scrutinizes some of the nation’s largest Medicare Advantage insurers for their use of prior authorization and high rates of denials for certain types of care. The subcommittee sought documents and information from the three largest MA insurance companies — UnitedHealthcare, Humana and CVS — and investigated their practice of “intentionally using prior authorization to boost profits by targeting costly yet critical stays in post-acute care facilities.”

The report found that between 2019 and 2022, UHC, Humana and CVS denied prior authorization requests for post-acute care at far higher rates than other types of care. In 2022, UHC and CVS denied prior authorization requests for post-acute care at approximately three times higher than the companies’ overall denial rates, while Humana’s prior authorization denial rate for post-acute care was more than 16 times higher than its overall denial rate. The report also found increases in post-acute care service requests subjected to prior authorization and denial rates for long-term acute care hospitals, among other findings.’

Apparently his company were one of the worst for refusing claims. I hope this makes other CEOs sit up and think about the business they are in.

To be clinical it’s also a pretty decent shot. Suppressors tend to make guns less accurate, the target is moving away from the shooter (in a video clip I’ve seen) and it’s dark, with no doubt a dose of anxiety about the escape route to add to the mix.

You live by the sword you die by the sword. You live by the invisible sword and you still die by the sword.