Back in the scary but innocent days of March 2020 the Government and NHS sought to maximise hospital capacity. This was surely the right thing to do, given the uncertainty of the pandemic, but many of its efforts backfired badly.

First, NHS Hospitals decanted bed-blockers without testing them for SARS-CoV-2. Some were infected, igniting lethal nursing-home outbreaks. Secondly, the Government commissioned Nightingale Hospitals to great fanfare. Unfortunately, as it should have perceived beforehand and soon discovered, there weren’t enough doctors and nurses to staff these facilities. The Nightingales quietly closed over the subsequent months, having treated derisory numbers of patients. Some treated no one at all. Half a billion of taxpayers’ money went pop. Third, the Government spent £2 billion to buy-up capacity at private hospitals, which did have staff, beds and expertise. The BMJ, whose article is worth reading in full, has managed – after multiple FOI requests – to analyse how this turned out, and it isn’t pretty.

In the BMJ’s words:

The major deal bought the entire capacity of 200 private hospitals, including 8,000 private beds, 1,200 ventilators, 700 doctors and 10,000 nurses, to help the NHS care for patients with COVID-19, with cancer, or needing urgent operations…

The national contract block booked beds, equipment, and staff… It allowed NHS teams to take over whole departments of private hospitals if necessary. NHS England agreed to pay for the bulk of the hospitals’ operating costs, including staff, consumables, rent, capital expenditure, building modifications and infrastructure.

According to the BMJ, the March 2020 plan was for this extra capacity to be used for Covid patients, but this changed in May 2020, with the independent sector told to concentrate upon elective patients whose surgery had been delayed whilst the NHS concentrated upon Covid. I believe that this was true of provincial England but that, from the start, the London plan was that the NHS would handle Covid whilst contracted private sites remained ‘Covid clear’ and undertook medical and surgical treatments that would otherwise be delayed.

When contracted beds were not needed by the NHS, the private hospitals remained free to admit paying patients, but with 60-85% of the income remitted to the Government. Readers should note, as an aside, that the Government effectively closed the posher London private hospitals to their Middle Eastern patient clientele owing to travel restrictions. This should have left the hospitals with substantial spare capacity and an urgent need for new income streams.

The NHS made little use of this pre-paid capacity for Covid. Through the March and April 2020 peak only 0.62% of the 8,000 contracted beds were used to treat Covid patients. On April 12th 2020, at the peak of the first wave, the NHS had almost 19,000 Covid inpatients, 2,881 on mechanical ventilation, whereas the contracted private sector had 52. Just 30 of the 200 contracted sites ever treated COVID-19 patients and one of these – the royalty-favoured King Edward VII – treated one Covid patient for one day, which sounds like an incidental case to me.

Low numbers are understandable if sites were told to concentrate on non-Covid care and, at least from May 2020, this was their core role. But there is one key point that the BMJ misses: few of the contracted sites can have had Covid outbreaks during the first wave. That contrasts with care homes and NHS hospitals, implying exemplary infection control, a view that tallies with my experience when I ran Public Health England’s reference lab for antibiotic resistance.

High-end London private hospitals regularly sent exotically antibiotic-resistant bacteria to the lab, seeking advice on treatment and a view on mechanisms of resistance. These bacteria largely came from Middle Eastern patients who’d previously been hospitalised in Saudi or the Gulf Region, some approached pan-resistance, and we’d scrabble to identify some obscure or developmental antibiotic that might be used. Crucially, though, I never once saw such a superbug cause an outbreak at a private hospital, whereas I saw and advised upon plenty of superbug outbreaks at NHS sites.

What’s more concerning than the paucity of Covid patients is how few non-Covid NHS patients were treated at the contracted hospitals. This was particularly striking for prestigious London sites. The 234-bed London Clinic provided just 896 NHS in-patient, outpatient and day case activities over six months for £28.2m received. That’s £30,000 per activity, which seems steep, given that not all ‘activities’ required the patient to be admitted. Numbers were similar for the BUPA Cromwell.

Underuse was general, though, and not confined to these high-end London sites, as revealed by how much private work the contracted sites could continue to perform. Across 29 contracted Nuffield Hospitals 64% of episodes of inpatient care during the first year of the pandemic were for private patients, not for the NHS cases for whom beds were reserved. At 36 contracted Spire hospitals the proportion was 62%, at Circle’s 47 hospitals it was 44% and at Ramsay’s 31 sites it was 27%. Together, these four groups accounted for 75% of the £2bn contract.

There is no suggestion by the BMJ (or me) that any site or hospital group wilfully avoided admitting NHS patients and instead prioritised paying patients. Rather, NHS patients weren’t being referred, leaving independent hospitals free to take those with insurance or who’d grown so frustrated with ‘our NHS’ that they chose to self-refer and to settle their own accounts.

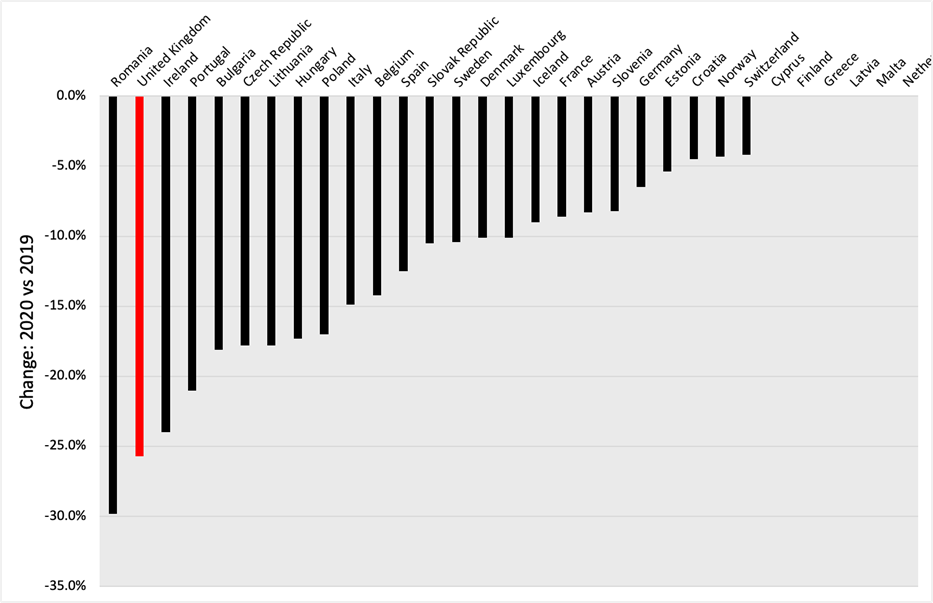

This underuse matters because, as the OECD reports, and the BMJ fails to stress, the U.K. was among the worst European countries at providing non-Covid medicine. During 2020 the U.K. saw a greater reduction in the provision of major cancer surgery than in any other European country bar Romania.

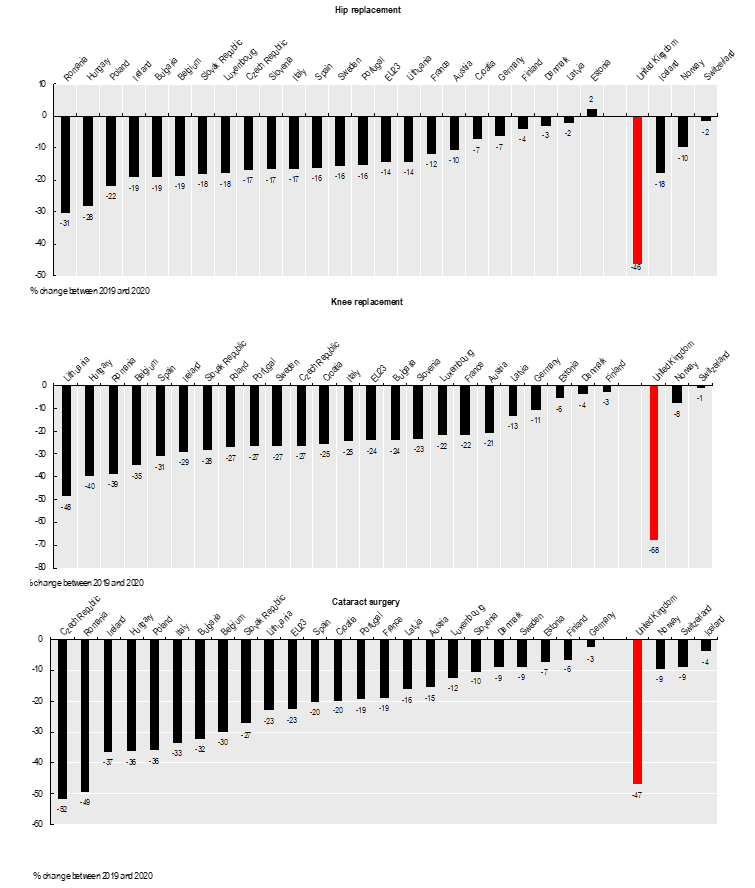

It was similarly bad for hip and knee replacements, and for cataracts.

The BMJ finds a few medics to justify aspects of the underuse, asserting that private sites weren’t suitable for Covid patients, or that one particular hospital ordinarily handled sports injuries and wasn’t always appropriate for complex orthopaedic patients managed at the NHS teaching hospital with which it was partnered. At one tiny 12-bed private hospital in Oxfordshire surgeons operating on an NHS patient were allegedly told to ‘hurry up’ because there was a private patient waiting.

It is right to point out these deficiencies, but they cannot account for massive underuse when, demonstrably, there were patients who needed treatment and weren’t receiving it.

High-end London private hospitals are well able to provide major cancer surgery. They do so for overseas patients in normal times. Joint replacements and cataract surgery are the bread and butter work for contracted provincial hospitals owned by Spire, Nuffield, Circle and Ramsay.

Some people will have died because they failed to receive cancer surgery. Many more will have suffered pain, immobility and poor vision owing to delayed elective procedures. The latter folk are now part of the NHS backlog, patiently awaiting their turn in ‘our NHS’, or shelling out from their own pockets for private surgery.

It needn’t have been like this. Hospitals were waiting and bills had been pre-paid. It is scandal that this capacity was not used. Allyson Pollack, Professor of Public Health at Newcastle University, told the BMJ that the Parliamentary Accounts Committee or National Audit Office should investigate. I concur, and hope that they interview Dr. Richard Packard, chair of the Federation of Independent Practitioner Organisations, who told the BMJ, “It was the NHS managers who were supposed to organise things,” adding that, “The NHS couldn’t organise a piss up in a brewery.”

Many frontline NHS healthcare staff worked with great dedication through the worst months of the pandemic. They deserve respect, whatever one thinks of lockdowns, masks, vaccines et cetera. The same cannot be said of ‘our NHS’ as an organisation.

Dr. David Livermore is a retired Professor of Medical Microbiology at the University of East Anglia.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

This is a classic symptom of an excessively siloed organisation. Targets are distributed to the relevant silos, which then execute plans to address the targets in splendid isolation. Strong organisations have multi disciplinary and multi departmental ‘boards’ that can review the individual execution plans and adjust them in the context of actual demand and the plans of other departmental silos. The board needs also to carry the operational responsibility for the hospitals and services, so they have an existential interest in making sure everything works together.

Or where no one is accountable for the bottom line and they can spend other people’s money freely. A bit like the entire public sector.

.

Looks like the downvoter works in the public sector.

‘… of an excessively siloed organisation. .’

Typo? I think you mean ‘soiled’.

Good old school highly centralised command and control Socialism is how the NHS “works”. Of course, it doesn’t. It’s massively over-bureaucratised, and Blair’s managerialism runs the show.

RUH in Bath. Senior nurse of over 20 years experience; I asked her what she thought of NHS management.

“Managers? Dickheads with clipboard who stop me working”

All you need in a nutshell. Though one could add, that these managers get huge salaries and pensions. Reward for ensuring the NHS does not work.

French insurance based system works just fine…

“Why the Health Service works in France”

https://edmhdotme.wordpress.com/why-the-health-service-works-in-france-11-2022/

“Unfortunately, as it should have perceived beforehand and soon discovered, there weren’t enough doctors and nurses to staff these facilities.” Perceived? No, all it needed was a health ministry analyst with a pencil, the back of an old envelope and 5 minutes to spare. They were probably otherwise engaged making midazolam consumption forecasts.

No need for the calculation, they knew already.

Since the 1990s the aim – consecutive Governments’ policy – has been to reduce bed numbers and medical and nursing staff levels because State funded/provided healthcare to deliver what it promises is unaffordable. 80% of expenditure is the payroll expense.

This is why Winter ‘flu crises have become endemic (sorry) in the NHS over the last three decades whereas not prior.

Well of course they were not needed.

when retired senior retired nurses offered their services, even for the mundane job of administering vaccine, they were required to submit to ludicrous personal checks; so one I know walked away.

M I can see it now in WWII when a volunteer tried to join the RAF:

yes sir, well I appreciate you want to do your bit but we have to ask if you have any bad feelings towards the Germans. You do, well sorry Sir you are not the sort we want. By the way, are you a Nazi?

“Back in the scary but innocent days of March 2020”

scary because freedom loving Boris became the Dictator he always wanted to be.

innocent because so many people were too stupid to see what was happening

*****

Stand in the Park Make friends & keep sane

Sundays 10.30am to 11.30am

Elms Field

near Everyman Cinema & play area

Wokingham RG40 2FE

When the “Nightingale” hospitals were created, it looked like a budgetary exercise by the MoD, with the Spring budget being just round the corner (although it never happened, because of the Lockdown etc). Demonstrating what they could do might have helped them out if financial cuts were on the agenda.

I’ve alway considered that a publicity stunt: By that time, large hospitals had reportedly been erected very quickly in China and the associated background whisper was They could never do this in England because The English System[tm] is so irrational and inefficient. Hence, someone set forth to demontrate that the British military still has the capacity for money-burning exercises like this. An anglo-sino military PR war, so to say.

Good! It’s just what the Our™️ NHS besotted, idiot British public deserve. More please.

I would have thought that one of the reasons private hospitals aren’t bedeviled with infections is because the majority of rooms are single with private bathrooms. The ward lavatories at our local big county hospital are filthy and smelly and compare badly with the average public lavatory, it’s no wonder that stomach bugs go round the place like wildfire.

I can never understand why the Victorian ward system still exists in the UK. It is dehumanising, noisy, lacking in privacy and undignified, especially on mixed wards, which are still around, despite protestations to the contrary.

The story I have been told was that govt bought the private beds en bloc specifically to ensure they were not made available to paying customers. Obviously the intentions were very honest and not in the slightest underhanded.

Of course not.

When pressure on the NHS is used to justify all kinds of experimental social engineering measures, mass-selling of useless pseudo-medical products like face masks and covaxxes and also, as covert driver all kinds of other policies some people always wanted to see implemented, eg, the teetotaller agenda or banning fireworks (Germany), anything which could relieve pressure on the NHS must be highly unwelcome. Methinks the scandal is not so much that the NHS couldn’t get this organized but that it didn’t want to get it organized.

Anyone surprised?

this was the public sector. And the NHS worst of all.