When did the coronavirus first appear and begin spreading? Did it emerge in December in the Huanan wet market, or did it leak from the Wuhan Institute of Virology in November, or was it intentionally released at the World Military Games in October? Was it spreading internationally during autumn 2019? Has it been around for years?

Here I’ll present evidence that the coronavirus appeared at some point in the second half of 2019 and was spreading globally during that autumn and winter.

There have been a number of studies that have gone back and tested stored samples for evidence of the coronavirus, either antibodies or viral RNA. One of the most intriguing is a study from Lombardy in northern Italy by measles researchers (Amendola et al.) who had spotted that Covid could cause a measles-like syndrome (though the evidence on this claim is not fully clear and a measles-like rash was not a widely publicised symptom of the disease). The researchers tested hundreds of stored samples taken during 2018-20 for both antibodies and viral RNA. Eleven of the samples were positive for viral RNA from August 2019 to February 2020, including one from September, five from October, one from November and two from December. Four of these were also positive for antibodies, including the earliest sample from September 12th 2019 (both IgG and IgM). A striking 25% of the samples from September to December were positive for viral RNA, which seems on the high side even considering these were samples from people visiting hospital with measles symptoms; the percentage positive then oddly dropped to 16.7% in January and February 2020. The positive samples were genetically sequenced to reveal mutation information, reducing the chances of them being false positives – though it should be noted that the positives were of partial sequences, not complete ones, so cross-reaction remains a possibility. In addition, none of the samples tested positive on a SARS-CoV-2 PCR test and the first to be positive on more than one RNA component – the first strong evidence of true infection – was from December 15th in Milan. Comparison was made with a control group of 100 samples from August 2018 to August 2019, none of which were positive on any RNA fragment, though 12 were positive for at least one antibody, a result which the researchers called “inconclusive”. Their results led them to estimate that the virus emerged around July 2019.

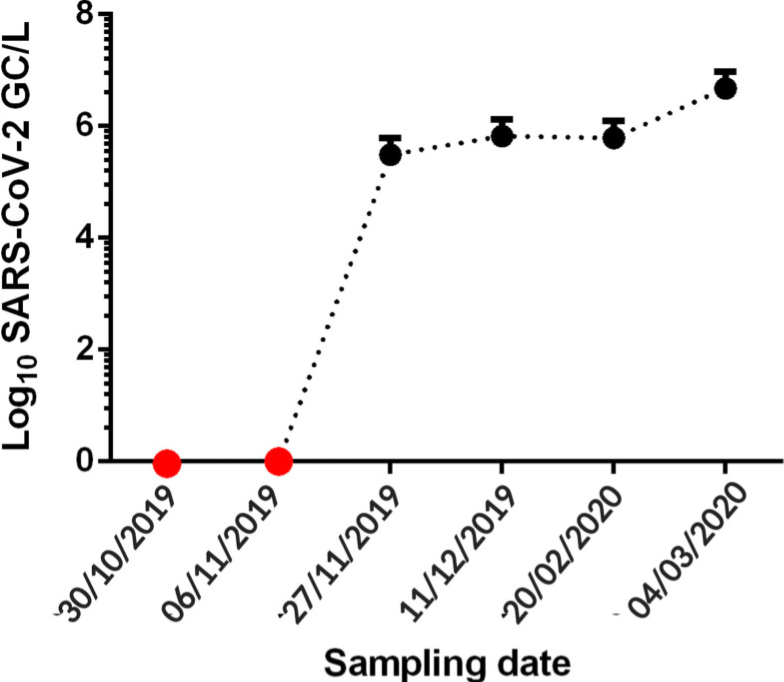

A separate study in northern Italy tested waste water from 2019 for viral RNA and found samples in Milan and Turin positive from December 18th, though negative prior to that, which is in contrast to the results of the first study – though in line with when the first strong positive turned up in Milan. The samples were again genetically sequenced, adding to their reliability.

A Brazilian sewage study found SARS-CoV-2 RNA in samples from late November and December 2019, but not in two earlier samples from October and early November. The samples were taken from one site in the southern Brazilian city of Florianópolis and were genetically sequenced for confirmation.

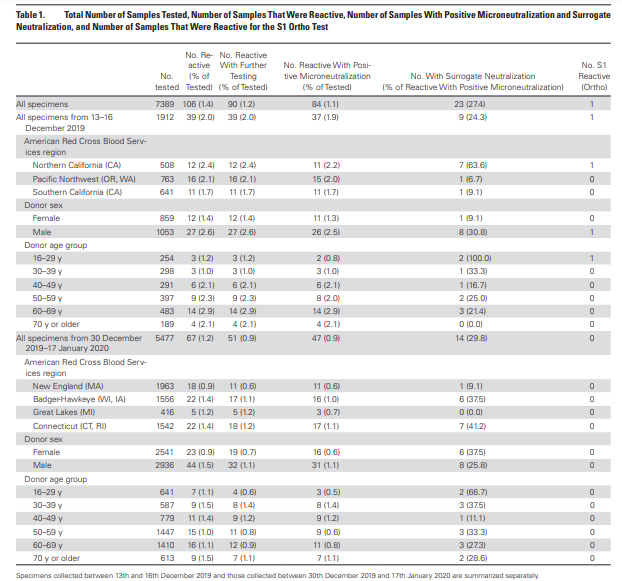

An antibody study of archived Red Cross blood conducted by the U.S. CDC found 39 antibody-positive serum samples collected December 13th-16th 2019 in California, Washington and Oregon. Overall, 2% of blood samples collected from these states on these dates tested positive for antibodies. The full results can be viewed in the table below. A 2% antibody prevalence in mid-December suggests significant community spread across America during November 2019. However, there were no earlier samples for comparison and no testing or sequencing of viral RNA for confirmation.

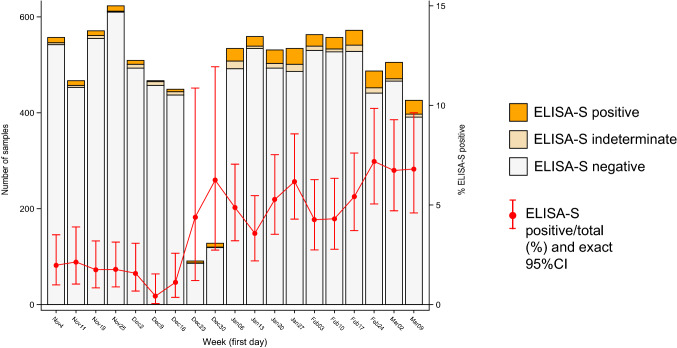

A study of stored blood samples in France examined hundreds of routinely collected samples in a population cohort and found around 2% prevalence of antibodies in November, rising prevalence in December and around 5% prevalence in January. These figures do seem on the high side when compared to the above studies, and the lack of testing and sequencing of viral RNA and the absence of samples from earlier periods suggest this may be less reliable evidence.

Another Italian study (Apolone et al.) tested blood samples from lung cancer screening for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and found 14% of those from September 2019 were positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, rising to 16% in October though oddly dropping back to 3% in January 2020. These pre-pandemic results are again on the high side and lack testing and sequencing of viral RNA as well as negative controls from earlier periods, meaning they may be cross-reacting. A Spanish study detected SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in a sample of waste water from Barcelona on March 12th 2019; however, all the other historic samples up to January 2020 were negative and it is suspected that this is a false positive due to contamination or cross-reaction (the sample wasn’t sequenced).

What about early spread in China? It’s hard to get reliable data for this country. However, a leaked Chinese Government report found hospital patients (recognised retrospectively) admitted in Wuhan from November 17th 2019, suggesting the virus was spreading there during November and probably October.

A molecular clock study estimating the date at which the common ancestor of early viral samples was around put the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 as early as July, in China. A separate molecular clock study estimated the emergence between mid-October and mid-November in Hubei province, China; another put the emergence between early October and early December and reviewed other studies which found similar. A fourth estimated an emergence in late October with global spread occurring throughout the winter.

There is considerable evidence, then, that the virus was circulating both in China and internationally by November 2019 at the latest. We can also say with strong confidence that it was not circulating prior to July 2019, and it may not have been around before October 2019, depending on how reliable the European data from the early autumn are.

Some argue that all this evidence of early spread – despite coming from multiple sources and using robust validation methods such as sequencing – must be faulty in some way, as the lack of excess deaths prior to March 2020 makes it impossible for the virus to have been spreading widely over the autumn and winter.

My view is that this argument is insufficient to overcome the clear evidence of early spread. I don’t deny that there is something of a ‘mystery‘ that must be resolved insofar as the waves of excess deaths did not begin until March 2020. Some sceptics resolve this ‘mystery’ by arguing that the virus must therefore be no more deadly than other similar viruses, and thus that any excess deaths since March 2020 must all have been caused by interventions such as lockdowns, faulty treatment protocols and vaccines. However, I agree with Dr. Pierre Kory that we have undeniable evidence of waves of severe pneumonia with a common clinical profile that began in March 2020 and that are best explained by the novel respiratory virus to which most of the deceased tested positive. While some of the excess deaths will be due to interventions, and some of the Covid deaths will be misclassified, the majority of additional deaths from a respiratory cause will be due to the virus. Professor John Ioannidis used antibody data to estimate that the infection fatality rate in the Americas and Europe in the first wave was around 0.3-0.4% (higher in hot spots), which is several-fold higher than flu, usually estimated at around 0.1%.

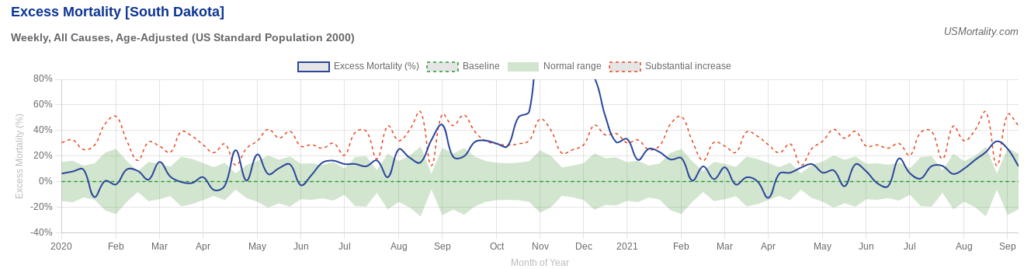

A good counterexample to the claim that all the excess deaths in the pandemic were caused by interventions and not the virus is South Dakota, which imposed very few interventions. Despite this laissez-faire approach it had a mild spring wave; yet then had a massive summer wave that resulted in greatly elevated deaths during the autumn. These deaths certainly can’t be put down to sudden panic: the state was so relaxed during its summer outbreak that it held a massive motorcycle rally.

So how to explain the lack of excess deaths during the autumn and winter of 2019-20? The most important point to be made is that while SARS-CoV-2 was clearly circulating during that winter, it does not appear to have been the dominant virus either in the community or in care homes and hospitals. Thus while, say, 2% of the population may have contracted the virus during the winter, because it was competing with other, milder viruses and wasn’t running rampant among the high risk population, its impact was limited and it did not cause noticeable excess deaths.

The early-spread-sceptic’s objection to this point is that the virus is clearly highly infectious so if it was present and circulating it’s simply not possible for it to have remained at a low level and not run rampant in, say, care homes, causing havoc.

But is it really true that the virus always causes a large wave of infections and deaths whenever it is present, and as soon as it arrives? The evidence suggests not. Just look at how it failed to take off in many places in spring 2020, not just South Dakota, but Japan, South Korea, Germany, Eastern Europe and large parts of the U.S. India notably wasn’t hit hard till Delta in 2021, and East Asia not until Omicron. In other words, the virus doesn’t always do what we’d expect, and in particular it doesn’t always cause a large, deadly wave as soon as it is present.

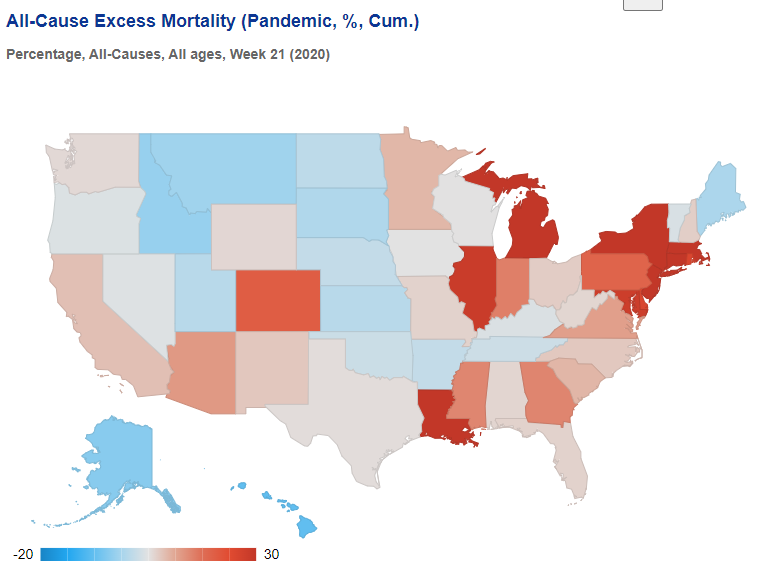

To illustrate, here’s the picture in the U.S. at the end of May 2020, after the initial wave. It’s a real patchwork, with clear concentrations of excess deaths around New York and around Michigan, Illinois and Indiana, plus Louisiana and one or two other states. Many other states had very few excess deaths during the spring. Yet we know the virus was circulating widely in every state.

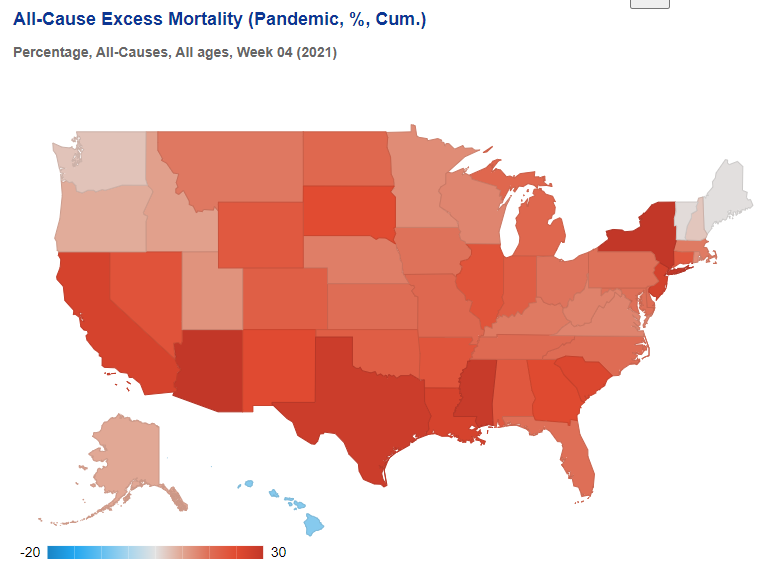

Then, by the following winter, excess deaths were high almost everywhere, meaning specific local treatment protocols or policy responses cannot be credited either with causing the deaths or averting them.

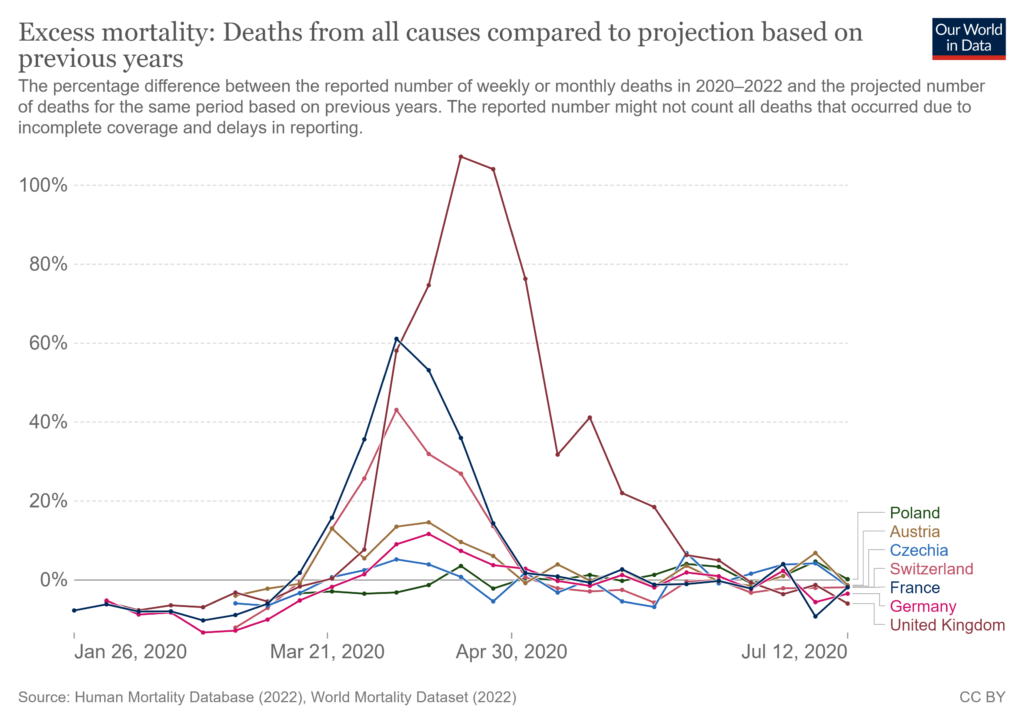

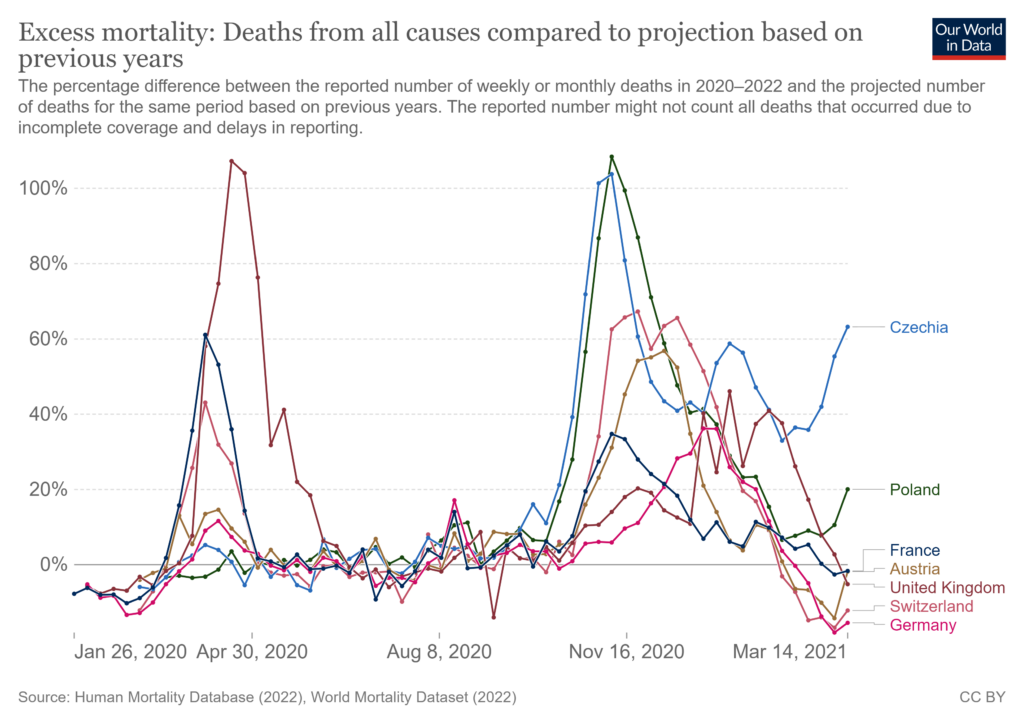

In Europe, too, there was huge variation in the impact during the initial spring wave, even though the virus was circulating everywhere.

This wasn’t owing to policy responses, as shown by the very different outcomes the following winter.

In line with these inconsistent outcomes, numerous studies have shown that outcomes during the first wave weren’t explained by policy responses. But they also aren’t explained by whether or not the virus was circulating, as it was circulating everywhere.

The evidence we have, then, from multiple studies with strong validation methods – including genetic sequencing of viral RNA – shows that the virus was circulating globally since November 2019 at the latest, with some evidence of its presence as far back as July, though not earlier than that.

The most likely reason there was not an explosive, deadly outbreak prior to March 2020 (or even later in many places) is that the virus was still in competition with other winter viruses so was not dominant or running rampant in hospitals and care homes. The large outbreaks from spring onwards may have been assisted by the emergence of new, more infectious (and possibly more deadly) variants. A winter Covid prevalence of around 2% largely among the low risk could easily go unnoticed among the usual winter diseases without triggering noticeable surges in hospital admissions and deaths.

On this evidence, then, it seems we can definitively rule out both an emergence before July 2019 (too many negatives and just one questionable positive) and after November 2019 (too many positives in a number of countries). The evidence is not currently consistent or robust enough to be able to pin it down more definitively than that.

There should, of course, be much more evidence on early spread. The World Health Organisation in June 2020 called for early spread to be properly investigated. However, very little has been done, and particularly in the United States, the various Government agencies have made no efforts to investigate early spread as part of their general neglect and squashing of all investigations into Covid origins.

Such silence and obfuscation only raises suspicions. And there is no shortage of reasons to be suspicious. The lack of genetic diversity in early samples, the high degree of adaption to humans from the outset, the absence of animal reservoirs and the presence of unique features that make the virus highly infectious among humans suggest that it was not natural but engineered, and thus either leaked from a lab or was released. Who was involved in the research that created the virus and the course of events that led to its getting into the human population is therefore a question of great importance that must continue to be pursued.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

I look forward to a time when grown adults going to some talking shop don’t feel comfortable moaning about “psychological safety” and feel ashamed even for thinking such a pathetic, narcissistic thought. I am pretty sure none of the people complaining have ever felt truly unsafe in their entire coddled lives- I know haven’t.

““However, psychological safety is a precursor to free and open debate and the need to subject ideas to scrutiny.” Which really means they don’t have the intellectual capacity to defend their ideas from a robust challenge. The latter being the bedrock of a democracy.

I consider the term “psychological safety” a bloody insult. Ooh, how progressive – psychological safety. A wholly fabricated Orwellianisation of words to provide a veneer of ‘science.’ Those throwing this term about are quite simply intellectual pigmies not far removed from nursery school children who cannot have their own way in the toy box.

As BB has pointed out, if they genuinely believed they had legitimate concerns they would have positioned themselves front, centre and loud and inviting debate.

The real solution here would have been to cancel the invitations to these fairies – with apologies to fairies.

The correct response is, of course, “If you don’t feel safe, perhaps you would better not attending”.

Psychological safety in this context = intellectually inadequate cowards.

a bunch of wimps why is everything about safety safety safety, really annoying times.

what happened to keep calm and carry on.

If people don’t feel safe when their views are challenged or discussed they need to keep their views to themselves and leave adults able to have respectful differences of opinion.

In other words, someone disagrees with you, grow up and get over it.

I listened to a talk by Baroness Hale last week. Her opinion is that upsetting people is not a crime…

What, pray is psychological safety? Is it a euphemism for contrary opinion?

The organiser needed to grow a pair. 7 wimps who don’t feel safe? They’re hardly the ‘Magnificent Seven’ are they?

These people need to go and live in a dictatorship or a war zone to learn what the concept of being “unsafe” actually means.

I see a dislike tick in every comment. Wonder if that person feels unsafe reading this article? LOL.

These people are simply lying. They ‘feel’ powerful enough to squash dissenting opinions. And hence, they’re doing that. They just need to add the right kind of Babble™ to have something which can pass as a thin justification for that. I appreciate that the late notice of this decision is not ideal for any parties concerned obviously means We’ve postponed telling you about our decision until the very last moment to ensure that you cannot take measures against it anymore.

Some sort of public protest against this kind of conference in Edinburgh would be highly appropriate.

Woketards make me feel unsafe and I don’t want them anywhere near my children; why does no-platforming only work in one direction?

So some felt ‘unsafe’ because someone had a different opinion than their opinion?

The wretched wokeville centre , if they had any intelligence, should have cancelled the other 7 & just invited Dr Cuthbert. The problem are the damned others