As I write these words I see that daylight is dimming, reminding me that it is the shortest day of the year. The winter solstice traditionally marks the start of the 10 day period when we take time off work to visit relatives and engage in general revelry before the arrival of the annual ‘collapse of the NHS’ that’ll take us through to the start of springtime. This year to join in with relative newcomer COVID-19 once again demonstrating its ability to re-infect everyone, we’ve got an influenza outbreak that looks set to rival that of 2010-11, high incidence of RSV, Strep-A threatening the old and young and perhaps a touch of human metapneumovirus to keep us on our toes. In the past few years we’ve also had a new tradition, where a senior representative of the U.K. Government is chosen to tell everybody to refrain from enjoying themselves over the holiday period in order to save the NHS, and to remind all to try to receive as many vaccines as their arms can handle – we’ve not had this yet this year, but I note that there’s still time for our authorities to slip it in before Christmas Eve. Given the imminent collapse of the NHS, perhaps it is a good time to discuss how well the Covid vaccines have been helping to reduce infections, hospitalisations and deaths from Covid, according to the data in the UKHSA’s Vaccine Surveillance Report.

It wasn’t until early September 2021 that the UKHSA started to include actual vaccine surveillance data in the Vaccine Surveillance Report. I’ve often wondered why they started to offer these data, as even in that September report the data didn’t support the ‘vaccines are good’ narrative. My favourite theory is that someone in authority, ignorant of the complexities of the immune system (that’s the vast majority of those in authority, if not all of them), demanded that the data be included to show the population how well the vaccines were bound to be performing…

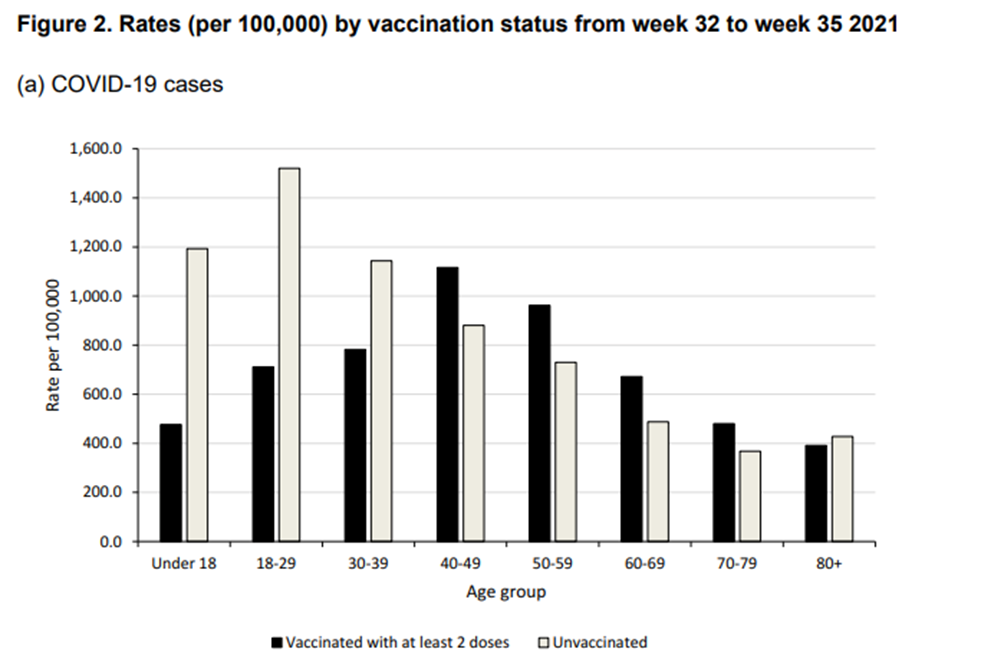

The data on infections first presented in the Vaccine Surveillance Report were troubling, showing an incidence rate of Covid in the vaccinated higher than that seen in the unvaccinated for those aged over 40.

In that first reporting of real-world incidence data by vaccination status, the UKHSA put only a small paragraph to remind readers that you mustn’t simply look at the data and infer how well the vaccines are doing:

The rate of a positive COVID-19 test varies by age and vaccination status. The rate of a positive COVID-19 test is substantially lower in vaccinated individuals compared to unvaccinated individuals up to the age of 39, and in those aged greater than 80. In individuals aged 40 to 79, the rate of a positive COVID-19 test is higher in vaccinated individuals compared to unvaccinated. This is likely to be due to a variety of reasons, including differences in the population of vaccinated and unvaccinated people as well as differences in testing patterns.

Of course, that final sentence is correct in that there are a multitude of reasons why raw data shouldn’t be interpreted simply. However, data based on population-wide testing tends to at least offer a strong indication of what is really going on. The real-world data on incidence presented in that Vaccine Surveillance Report were highly suggestive of a problem that should have been prioritised for rigorous investigation, not explained away with the flick of a pen.

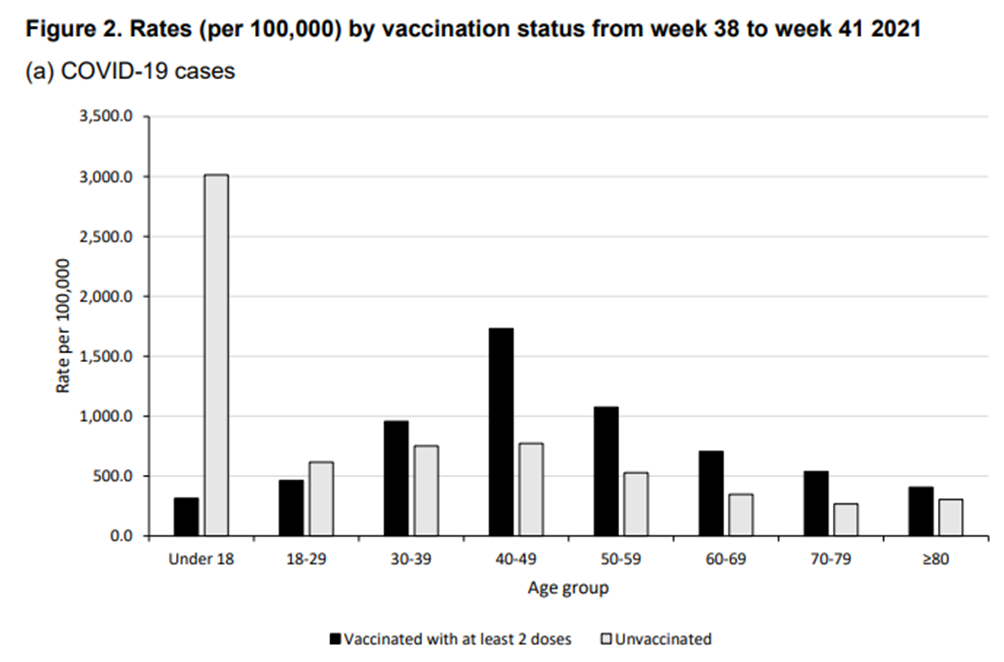

Six Vaccine Surveillance Reports later the situation had deteriorated, with rates in the vaccinated higher than in the unvaccinated for all those aged over 30, with significantly higher rates for those aged 40-60.

After a few more weeks of the apparent deterioration of the vaccines’ protection, the UKHSA gave up on the helpful charts (presumably they were too easy to interpret how bad things were getting), but they were still publishing raw data in tabular form and they continued to include ever more text warning of the dangers of interpreting these data ‘at face value’. By November 2021 the UKHSA had resorted to including a stern warning in bold in its section on real-world data:

These data are published to help understand the implications of the pandemic to the NHS, for example understanding workloads in hospitals, and to help understand where to prioritise vaccination delivery. These raw data should not be used to estimate vaccine effectiveness.

Again, their polite request not to look at the real-world data with an open mind hid the real problem – that they preferred to believe that it was the real world that was wrong and that their cleverly constructed experimental studies that were right (despite there being a lack of evidence supporting these experiments’ core assumptions, as described in an earlier post).

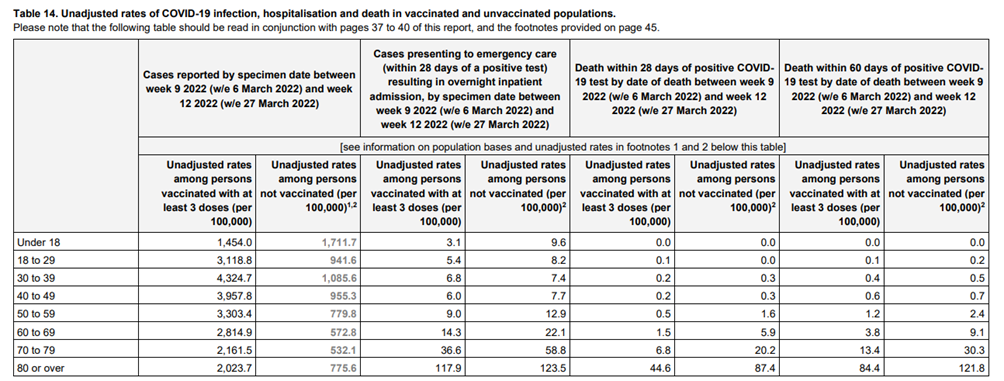

The final tables on real-world incidence data came at the end of March 2022:

The last set of data on infection rates (first two columns in the table) strongly suggested that the vaccines were significantly increasing the risk of infection with Covid. Of course, the UKHSA were keen to suggest that the differences seen between vaccinated and unvaccinated infection rates were actually due to… well, anything that they could think of that wasn’t ‘the vaccines’:

The vaccination status of cases, inpatients and deaths should not be used to assess vaccine effectiveness because of differences in risk, behaviour and testing in the vaccinated and unvaccinated populations. The case rates in the vaccinated and unvaccinated populations are crude rates that do not take into account underlying statistical biases in the data. There are likely to be systematic differences between vaccinated and unvaccinated populations, for example:

- testing behaviour is likely to be different between people with different vaccination status, resulting in differences in the chances of being identified as a case many of those who were at the head of the queue for vaccination are those at higher risk from COVID-19 due to their age, their occupation, their family circumstances or because of underlying health issues

- people who are fully vaccinated and people who are unvaccinated may behave differently, particularly with regard to social interactions and therefore may have differing levels of exposure to COVID-19

- people who have never been vaccinated are more likely to have caught COVID-19 in the weeks or months before the period of the cases covered in the report. This gives them some natural immunity to the virus which may have contributed to a lower case rate in the past few weeks

The UKHSA authors were correct to point out some potential reasons for the very high incidence of Covid in the vaccinated population, but they left one potential reason out: that they’d used a poorly tested vaccine that might have resulted in an increase in the risk of infection, a.k.a. negative vaccine effectiveness. To include this potential reason would have been supported by prior research into candidate vaccines for coronaviruses (including SARS and MERS). Alas, we’ve gone far beyond the realms of ‘trust the science’ and it is clear that no-one in authority is allowed to even whisper the potential for the vaccines to have made things worse.

We’re now nine months from that last table of real world data on Covid infection by vaccination status, and in the meantime studies from from around the world continue to suggest that the vaccines increase the risk of Covid infection. The most recent study into the impact of the vaccines on Covid infection risk was published last Monday – this well-constructed analysis of infections by vaccination status in healthcare workers in the U.S. state of Ohio showed that disease risk was significantly correlated with the number of vaccine doses given, with those having received three doses of vaccine being approximately three times more likely to get infected with Omicron variant, compared with the unvaccinated. Perhaps if the UKHSA had been more interested in having an open mind compared with its ‘it’s anything but the vaccines’ attitude towards the data it presented there might have been more caution taken with the vaccine rollout and as a consequence we might currently be seeing far fewer than 1 in 20 of the population concurrently infected with Covid.

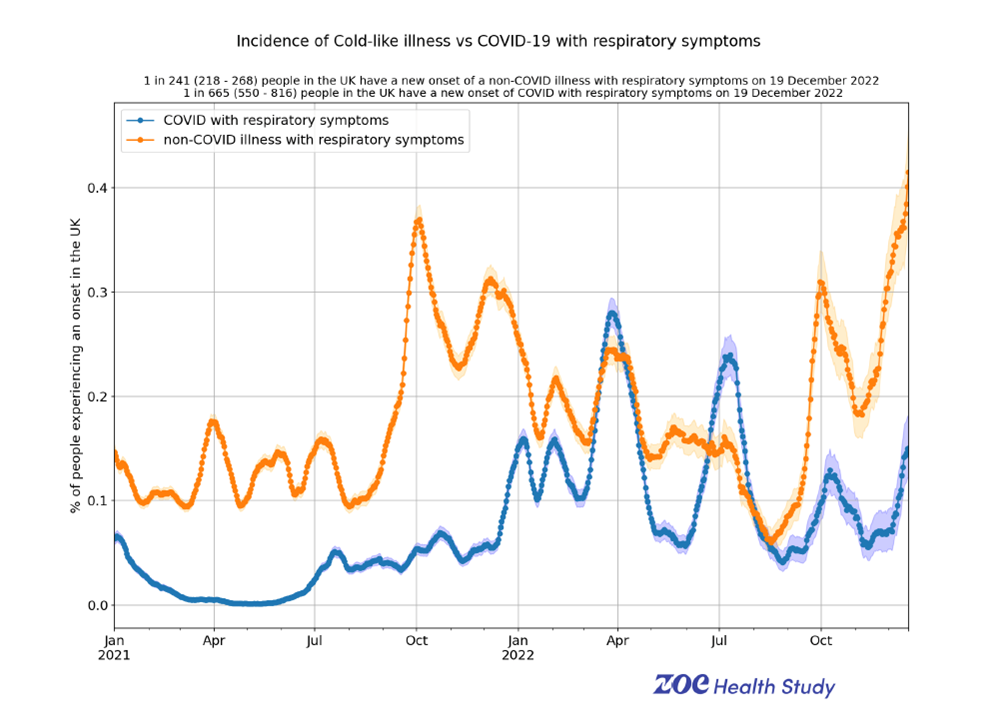

I’d also note (yet again) that the ‘test-negative case control’ method discussed at length in a previous post will give misleading indications of vaccine effectiveness if the vaccines are associated with an increase in ‘similar to, but not Covid’ infections. Recent data from the Zoe symptom tracker suggest that this might indeed be going on, showing a remarkable correlation between infections with Covid and infections that have similar symptoms to Covid but that aren’t.

To put it plainly, on a single day (December 19th) around 0.4% of the population developed a new non-Covid respiratory illness (‘cold’), while around 0.15% of the population developed a new Covid infection – are the vaccines also responsible for a general decrease in immunological protection from other diseases? I have previously discussed some of the potential complex side-effects of the vaccine. Yet another is the potential for the vaccines to generate autoantibodies against interferons, chemicals produced by the body as an early immune response to viral and other infections. These autoantibodies would act to reduce the ability of the interferons to impair viral replication, increasing the risk of a variety of diseases to fully take hold in those exposed to the viruses that each of us encounter every day but which are normally dealt with before the infection becomes sufficiently established for people to suffer symptomatic disease. Interferons also act to modulate the innate and adaptive immune responses, so an impaired response might also impact on the risk of bacterial infection. Note that if this is occurring then all in the population would be impacted by increased infection levels given that some in the population would have an increased propensity to become infected and thus infect others. There is some evidence that Covid vaccination does indeed introduce a risk of generation of interferon autoantibodies, as recently discussed in a vlog by Dr Philip McMillan. This is yet another aspect of the impact of the Covid vaccines on the immune system that deserves much more scientific investigation than has been undertaken to date.

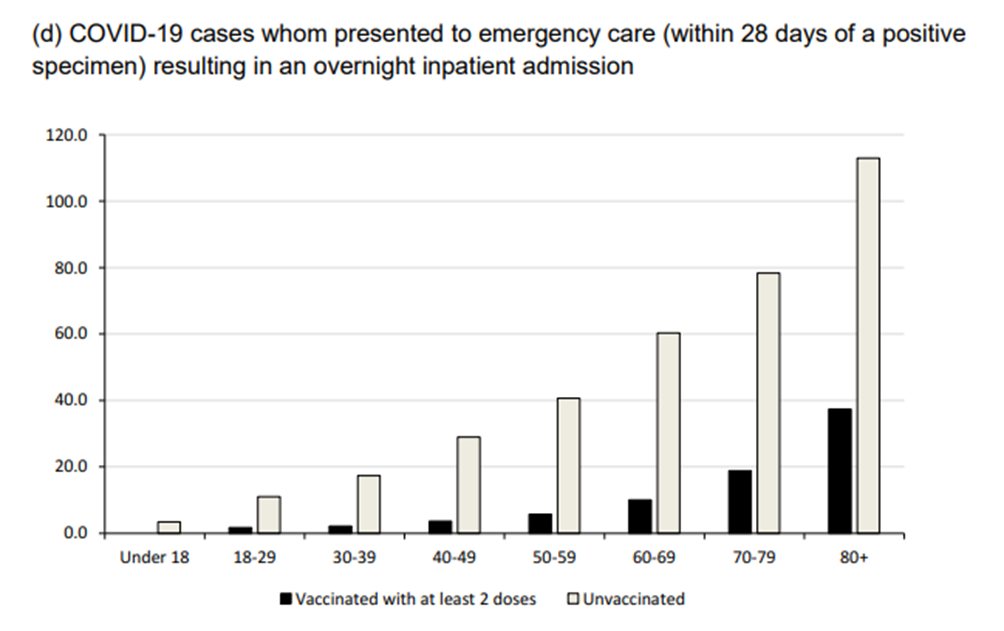

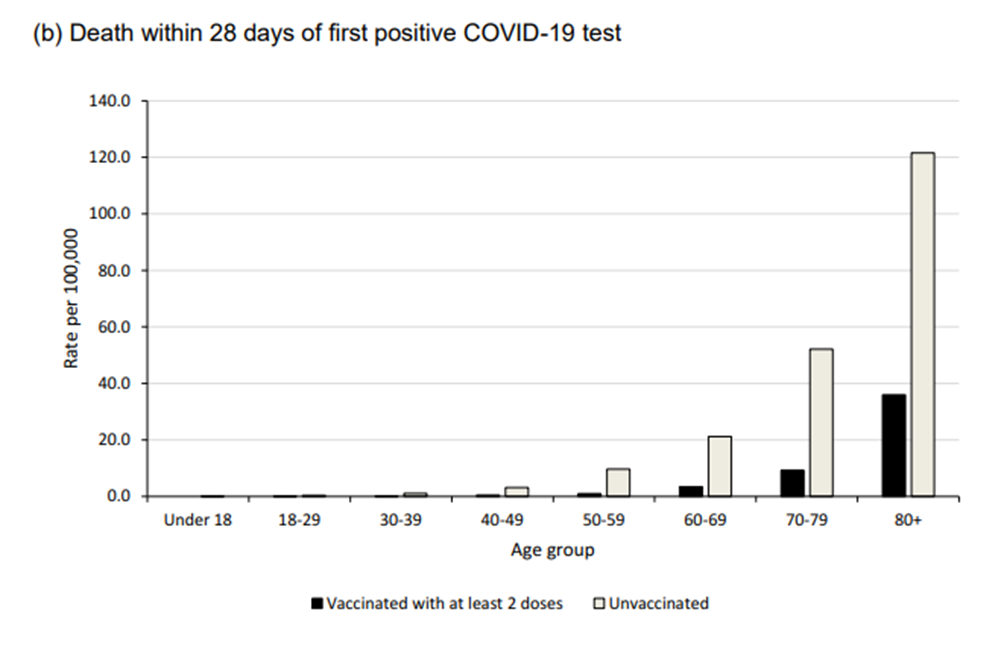

The table of infections by vaccination status presented a little earlier in this post does, of course, show more than just the infection data. An important aspect of the vaccines is their supposed protection against hospitalisation and death. Back in April 2021 the vaccines certainly appeared to offer significant protection against the most serious of outcomes.

It is important to point out something largely ignored by the Vaccine Surveillance Reports. What is clear from the graphs above is the significant effect of age on the risks from a serious outcome following an infection with Covid; those aged under 50 were always at a lower risk of hospitalisation and death. Beyond that, these raw data don’t take into account morbidities. Even the lower rates of hospitalisation and death seen in those aged under 50 hide the fact that very few healthy younger adults ended up in hospital as a result of Covid and even fewer died – the problem was with those younger adults who had significant morbidities (that’s not to dismiss the risk to the vulnerable, but the mantra that ‘everyone is at risk’ was unhelpful). It is also unclear regarding the impact of any ‘healthy vaccinee’ effect in those early months (i.e., because individuals ‘close to death’ weren’t given the vaccine, and were more likely to have a serious outcome from what would be a benign infection in a healthy individual).

The other aspect of the data not entirely clear from those charts is the significant reduction in risk seen with time. The UKHSA data suggest that the risk of hospitalisation and death saw a 10-fold fall in the seven months between September 2021 and March 2022. The claimed effectiveness of the vaccines at protecting against these serious outcomes must be interpreted with these lower absolute risks in mind. Is a vaccine with a 50% effectiveness at protecting against hospitalisation and death offering much real-world value if the risk of hospitalisation and death faced by an unvaccinated individual is relatively low compared with day-to-day risks?

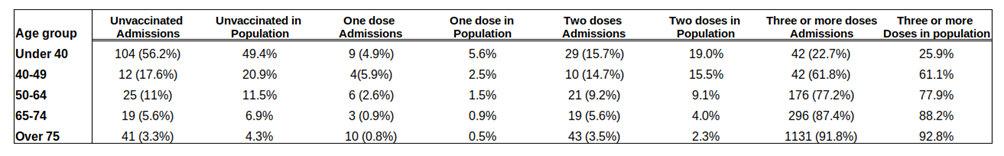

Even if the vaccines once offered protection against hospitalisation and death, is it still the case? Since August 2022 the Vaccine Surveillance Reports have been including real-world data on hospitalisations from the UKHSA’s Severe Acute Respiratory Infection (SARI) Watch system. In November’s report these data suggest the following hospitalisation figures for the subset of hospitals included in the SARI-Watch data:

Oddly, the UKHSA data table didn’t include any data on the proportions vaccinated in the SARI-Watch areas, only the proportions hospitalised by vaccination status – I’ve included the proportions vaccinated for England in the table above, which should be close enough for comparative purposes. It should be clear from the table that there doesn’t seem to be any significant impact of the vaccines in reducing hospital admissions – the proportions hospitalised for each age group and vaccination status generally match the relevant proportion vaccinated in the population.

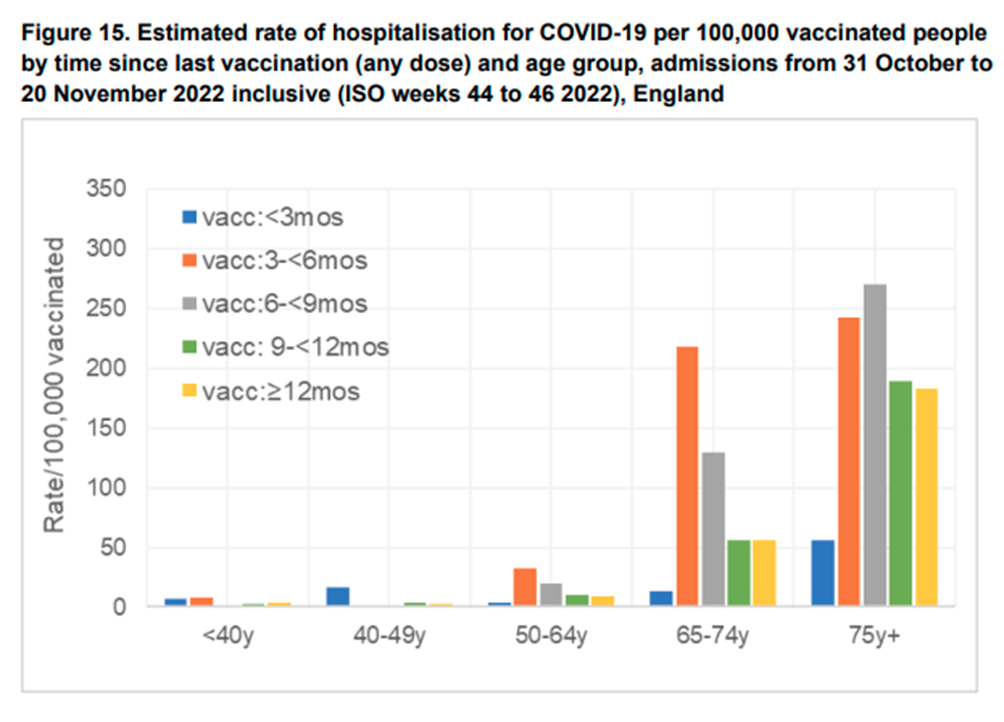

The section covering the SARI-Watch data also includes charts for the proportion of hospital admissions by the period of time since each admitted individual’s last dose of vaccine. The most recent chart is shown below.

This chart suggests that for those aged over 50 there might be a short period of vaccine effectiveness, but this is soon followed by a period of significantly increased risk of hospitalisation which gradually reduces over a 12 month period. Even worse, for those aged under 50, these data suggest that the vaccines offer an immediate increase in risk, albeit there appears to be a silver lining in that the risk soon dissipates.

Given this apparent lack of effectiveness of the Covid vaccines in reducing hospitalisations, it is odd that official guidance is still for the vast majority of those in the UK (all aged over 5, and soon to be all aged over 6 months) to receive a full course of a Covid vaccine. Are the U.K. experts responsible for advising Government paying any attention whatsoever to these real-world data?

Looking back from where we have ended up, it should be fair to ask whether there was ever any benefit in vaccinating those at low risk from Covid. Even given the uncertainties surrounding the Covid vaccines in early 2021, would we have gained nearly all of the supposed benefits by vaccinating only those most vulnerable? If we had taken this approach then the potential risks of the vaccines wouldn’t have affected the majority of the population. Indeed, if we are indeed seeing negative vaccine effectiveness, then we will likely be having much larger Covid waves that could well be resulting in more hospitalisations and deaths in the vulnerable, compared with if we’d vaccinated only those individuals actually at risk from Covid.

That brings us to the end of this series of posts reviewing the UKHSA’s Vaccine Surveillance Report – a document released by Government when we needed it most, but which delivered as little as it could beyond the propaganda value. That said, perhaps we should be grateful that statisticians and epidemiologists in the UKHSA persisted with presenting data that clearly showed the deterioration in the protection offered by the vaccines, even if the text that was written was so very keen to divert attention from the data elephant in the room.

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading the instalments over the weeks. Oh, and do enjoy your Christmas break, no matter the attempts of our Government to spoil it.

Amanuensis is an ex-academic and senior Government scientist. He blogs at Bartram’s Folly – subscribe here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Whilst I’m sure the guts of this article are correct I’m not sure there is now much value in getting in the knotted weeds if it all. COVID was never a huge threat and was all a massive scam to make RNA vaccine makers/sellers colossal sums of cash. WW1 was probably the same for the armaments industry, the state weaponised against ppl.

Indeed, I’m of the opinion that almost all publicly available information is expressly designed to propagandize i.e. tell you what you’re supposed to think. Those of us who had become aware of the lies and deceit going on with regard to climate change almost instantly spotted the same techniques with covid.

With the ongoing release of the Twitter files we’re seeing how social media is controlled, and of course this is happening with all forms of media, including search engines and Wikipedia. Absolutely nothing can be trusted to be reliable or truthful or even-handed.

In fact I pretty much take the view that all popular narratives on every subject are lies, designed to manipulate the public in the interests of those with power and control, and none of it is ultimately in our interests.

Covid, climate, Ukraine/wherever the PTB are currently laundering the public’s wealth, nations/borders/immigration, the illusion of democracy, globohomo/feminism/trans/gender, race/racism, religion… this is not by any means a comprehensive list!

In fact I pretty much take the view that all popular narratives on every subject are lies,

And that is exactly where I am at. Prior to the Scamdemic I tended to take a sceptical view of anything from “officialdom.” As the Scamdemic rolled out and I knew it was being rolled out my view that everything from officialdom was a lie was sealed. Now there is no going back.

Sadly, I am now at the point where I am questioning every aspect of our history:

The Miners strike.

World War ll

World War l

And so on.

Yes it was a huge scam and not a threat to the vast majority. It is also my theory that flu never did ”disappear”, conveniently usurped by this one virus to rule them all! Perhaps any doctors on here can attest to the fact flu was being tested for, because it would seem that every other respiratory virus legged it and the myopic focus was on Covid and solely testing for this particular virus. I think all existing influenza like illnesses ( ILI ) got attributed to Covid as a way of increasing the fear and hysteria ( and those all important numbers ) so that people would be more inclined to take a jab as soon as they were available. It’s really shameful that the vast majority of people ( including doctors, remarkably ) fell for this hoax hook, line and sinker. After all, ”you can’t find what you’re not looking for.” So if all they tested for was Covid and nothing else what did people really think was going to happen? Cue your casedemic right there.

If you designed PCR tests for every known virus and dialled up the thresholds I wouldn’t be at all surprised to discover that we’re all walking plague-ships, carrying around a host of bugs at any moment in time.

When you’re under the weather, run down, stressed, lacking essential vitamins etc. one of them will overcome the immune system and you come down with something.

I seem to remember an incidence in some god-forsaken place like an arctic research station, where everyone had been quarantined before visiting and they still had an outbreak.

Indeed. I read the Arctic story. Of course they couldn’t stop shoving sticks up their noses even when ‘on station.’

Bloody crackers.

That’s part of the reason I wrote this series.

Covid never was a huge problem, but the vaccines have introduced a different set of problems.

We’ve just seen the UK government sign an agreement with Moderna to produce 250 million doses of mRNA vaccines a year targeting a series of viruses, yet the experience of the one mRNA vaccine that has been developed is negative.

I note that it usually takes at least 10 years to go from candidate vaccine to authorisation for use (outside of clinical trials), thus this agreement is very troubling. Are we going to find that they say that the technology is ‘safe and effective’ and thus new vaccines can be produced based only on an antibody response? I also fear that if they’ve signed up to 250 million doses they’ll want to make sure that they’re getting ‘good value for money’, so perhaps there’ll be a more than a little encouragement to make sure that none of these doses are wasted…

Precisely. The fact, which is totally irrefutable at this point in time, that their precious, much-hyped, “only way out of this pandemic”, magic-bullet gene-therapies fell way short of their “safe and effective” advertising slogan hasn’t stopped them plowing on with the agenda and creating yet more mRNA toxic bioweapons says it all really doesn’t it?

And at what point do the various adverse event reporting systems get ditched as, much like the regulators, they appear to be mere theatre and neither use nor ornament. It’s business as usual and “carry on regardless” for these criminal psychos.

Thanks for another thorough deep dive article Amanuesis. I wondered what you think of Igor Chudov’s latest, where he cites a study about immune tolerance, whereby your body cannot effectively clear the virus, being responsible for excess mortality. It’s very interesting;

https://igorchudov.substack.com/p/booster-caused-immune-tolerance-explains

He also shows data from Germany, comparing regions within the country, which appears to demonstrate a high correlation between booster rate and excess mortality rate;

https://igorchudov.substack.com/p/covid-boosters-are-killing-germans

The substack from Igor, referencing work by Rintrah Radagast, seems to be very important. If they are correct, it would explain the increase in rates or RSV and the anecdotal increase in people either getting Covid repeatedly or just getting ill and not clearing the virus. Certainly almost everyone I speak to at work is either ill or getting over something. Now perhaps that is confirmation bias but if you take it together with the data on excess mortality and the statistics on hospital admissions, it is very concerning indeed. If only someone had warned them that carrying out an experiment on billions of people at the same time was not a smart move.

“If only someone had warned them that carrying out an experiment on billions of people at the same time was not a smart move.”

I don’t believe they carried out an experiment. Whatever happened was intended to ensure that everybody accepted the injections.

On that, fortunately, it failed.

It is rather troubling. IgG4 induced tolerance would lead to a subset (probably not all) suffering from symptomless chronic infection (similar to Typhoid Mary) and thus acting as a viral reservoir ensuring that Covid continues to circulate at very high levels. I note that the ‘mainstream view’ of Covid is that it is ‘serious Covid’ that results in hospitalisation/death, but that is an immune over-reaction to the infection which is going to be far less likely in those tolerant of their infection — instead you’ll see problems emerging due to long term high(ish) viral loads. I suspect that this will result in higher risk of cardiac problems and possibly neurological problems, but the (potentially) longer term viral loads could result in a variety of problems.

What’s so remarkable is the evidence that is emerging of a wide range of immune problems post vaccination, including tolerance, autoantibodies, other autoimmune problems, etc.

I am assuming that these figures relate to people hospitalised with a positive Covid 19 test and suffering from a respiratory infection.

There must therefore be further cases to add to this grim toll from people suffering from all forms of vaccine damage.

It is worrysome that there’s so little investigation into how the problems that we’re seeing in the population might correlate with vaccination status.

And I think that’s not going to change, even more worryingly, considering the imminent growth of the mRNA vax industry. Trying to be more realistic than pessimistic here but it’s become a fine line between the two.😐

Indeed, but sadly it’s not a surprise. The covid scam seems to me unique certainly in the history I’m aware of in its scope, globally, politically and institutionally and among the general population. Normally with some kind of fraud or conspiracy or folly there are significant forces who opposed it or didn’t go along with it who have some incentive to expose the truth. With covid, can anyone think of a significant body of any kind (state, media, academia, business, public health, science, the general population, judiciary, political opposition etc) that was not an enthusiastic supporter of lockdowns and vaccines? A few maybe, but a vanishingly small number. There’s simply no incentive for anyone to break ranks, even among the public who probably know in their hearts that they’ve been had.

I’m sure that the MHRA/Dame June Raine and the UKHSA/JCVI Dr Jenny Harries are well aware of this data.

I have every confidence that if they thought there was absolutely anything in these figures to worry about they would have immediately alerted the public.

We should have every confidence; after all they are fully independent and the head of those bodies have never had any ties or allegiances whatsoever.to pharmaceutical companies.

Anyone who suggests otherwise is guilty of spreading misinformation.

On a serious note – a big thank you Amanuensis for all the hard work, knowledge and wisdom which you so ably impart.

Don’t overdo elementary irony. Eventually, no one will be sure whether you mean what you say, at face value. or the opposite.

😀 😀 😀

Apologies for the lack of activity from myself on these pages for a fair few weeks; a combination of being unable to login and then pay my donation has kept my razor sharp comments and insights from the board 🙂 TBH, I am so tech illiterate I am surprised that I manage to function on the net at all!

Firstly, another brilliant article, thank you @Amanuensis. Secondly, a belated “hello again” and “Merry Xmas” to all the regulars here for continuing to fill BTL with such pertinent observations; even when previously active on the site I found little need to comment often because pretty much everyone who contributes says exactly what I would wish to say, but does it a whole lot better.

Having, with a few exceptions, cleansed myself of contact with people that I see as covid fanatics, (my mum, my partner, my brother are all unjabbed….I rarely hear any pro covid narrative face to face anymore),it is less usual now for me to encounter any jaw dropping bits of nonsense, even through my infrequent visits to the MSM, (to see what the enemy are up to).

This however, gave me a reality check, (as i suppose I live in a bit of a covid/climate change/ukraine, it’s all a load of shite bubble), at just the sheer lack of insight going on.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-south-scotland-63987721

Sadly, there must be tens of thousands of useful idiots in the country like this, with a trail of devastation in their wake that is completely invisible to them. Obviously avoided any kind of discussion about the injuries she may have caused and presenting herself to readers with a sense of pride and achievement.

The BBC of course will know that these people have ruined the lives of many, but shamelessly parade these “heroes” for the rest of the sheep to admire.

Sorry, have rabbited on a bit much; must be the euphoria of managing to finally get back on DS!

Welcome back. I have avoided everything about the BBC for getting on five years now. It started with cancelling my tv licence but soon extended to any and all BBC content and specifically the website. Everything they do now is little more than propaganda.

Yep, license cancelled about a year and a half ago, never watch or listen to their programmes, (even the so called “entertainment” is thinly disguised propaganda), but I do very infrequently check out what their “news” output is doing. Forewarned is forearmed sort of thing.

Anyway, thanks for the welcome back 🙂

I actually feel a bit sorry for these ‘footsoldiers’ — they genuinely believe that they’re doing good; I imagine that many will be horrified when (if) the problems introduced by the vaccination campaign become accepted.

Those in positions of power (that should have been more careful); those politico-scientists that pushed an untested solution to an exaggerated problem; the media darlings and celebrities that pushed something they didn’t understand; the scientists that took the money and turned a blind eye — they’re far more guilty of creating the mess that we’re in.

My main worry is that the problems/dangers of the mRNA vaccines will never be accepted.

Bigpharma have had decades of being able to swat aside criticisms. They seeped into med. schools and government after WW2 (A Big Thank You to the Rockefellers) and have been ably assisted by the likes of Gates, Blair, Fauci ever since.

Capturing the MSM was a cake walk.

That’s what we’re up against.

Most of the sheep now just want to forget and “move on”.

The mRNA platform has been deemed safe – so shortly there will be a jab rolled out for every “disease” they can think of.

I’m sorry to say it, but imho the only chance we have of opening eyes is that the deaths and chronic illnesses increase vastly to the extent whereby even the likes of the BBC can’t ignore the culprit.

Oh I’m sure these criminals will continue to declare their “countermeasures” safe even if the excess mortality and low birth rates continue throughout 2023. They’d deny all causality if they were stepping over dead bodies in the street, such is their wicked objective and total lack of conscience or ethics.

But one thing they can’t bank on is the same amount of dozy muppets believing their abject lies and swallowing the propaganda now as did in 2020. They can spout all the claptrap they like but nobody’s obliged to believe it or comply with it. I refuse to believe people are as naive or thick as they were at the beginning. It’s our only hope really because certainly nobody in authority is coming to save us or put a stop to this blatant democide.

With the possible exception of Ron DeSantis. We’ll see.

Agree to some extent about those in “command” of the “footsoldiers”, (to keep the military analogy going) are more culpable, but surely the trained nurses and medics “firing the rounds”, must know they are doing wrong?

Most will have had the (dubious) advantage of being better educated than a lot of us who have called this as a scam from the start.

Myself…factory worker, no degree, my brother…empties the bins, my mum….untrained care worker, plus a few of the delivery guys that come to us, the guy that runs the chipper….and so on…..not particularly academic, but bright enough to immediately see the big lie.

I’m not disagreeing with your point, but experienced and supposedly well trained “health professionals”….I expected better, (as we all did).

Welcome back BTW. I’ve not seen your name round these parts for a looong time!😺👋

Cheers! Been reading the comments section most days and enjoying the stuff yourself and the other regulars are consistently posting….thanks for that! 🙂

A fitting epitaph for these official reports. And with a small revision could probably sum up the UKHSA itself.

Thank you for all of the hard work and interpretations that you have done.

You should not vaccinate when the pathogen is proliferating, for the same reason you should not over-use antibiotics; you simply stimulate the emergence of new variants that are immune to this year’s vaccine.

Former top White-House aide Dr Paul Alexander has said the pandemic will never end like this. Every year brings a new variant needing a new vaccine.

The tole of natural immunity is being outsourced to Pharma.

Every year, measles used to kill perhaps 2 in a million children who did not inherit natural immunity from their mothers. Now, no child inherits natural immunity: vaccination has eradicated it, clearing the field for vaccine profiteering.

Dream marketing, if you are wicked.

In the 1870s, a campaign in England began against smallpox vaccination, which had been compulsory by law for 50 years. You went to prison if you refused. The campaign slogan was ‘Fraud, Force, Failure’. The vaccine manufacturers were making fortunes, take-up was mandatory, and huge smallpox outbreaks still occurred.

Plus ca change!

I worry that we’re moving from a massive industrial-military complex that influences world affairs to make things worse and make huge profits,

to a massive industrial-medical complex that influences world affairs to force their ‘solutions’ to make things worse and make huge profits.

Then again, I suppose we’ll merely end up with both.

The Medical-Pharmaceutical-Government Complex.

The public health industry, allied to the “safety” industry, will doubtless continue to expand and talk up the “need” for them to have more money and power. Safetyism is destroying Western civilisation.

As well as vaccinating during an epidemic being contraindicated, RNA viruses mutate and evolve so quickly that vaccination even outside an epidemic is useless as it only encourages new vaccine-resistant mutants to emerge and circulate. Vaccination then gives a false sense of security.

And this is precisely why it is not UK practice to mass vaccinate animals against Foot & Mouth disease – caused by an RNA virus. We know it doesn’t work in animals, so why should it work in Humans?

It is also why there are no effective vaccines against the plethora of other respiratory viruses and we have a pretend vaccine for ‘flu which despite decades of vaccinating with ‘new’ vaccines, ‘flu still circulates some years serious, other years not and the money-making band wagon continues on.

Measles: fatalities from Measles were in significant decline prior to the use of vaccines, most probably due to better nutrition and hygiene. If vaccines eliminated Measles, why is nearly every young child still being vaccinated?

The link between vaccination and reduction of presence of pathogens or reduction in fatalities is only ever considered in isolation of other factors such as sanitation, hygiene, nutrition, treatments and is over-estimated, but it is good business for Big Pharma.

It would be interesting to see research into why there has been a steady increase in cases of asthma and food allergies concomitant with increased, multiple vaccinations of children – given that vaccines mess with undeveloped immune systems in children.

http://vaccinepapers.org/

Beware the adjuvants.

Aka known as the dirty secret of immunologists/vaccinologists.

The amazing thing is that nobody knows the precise way in which they work ie keep the immune system boosted against the supposed pathogen.

But hey, never mind the “side” effects – they’re mainly years down the line – so nobody takes notice.

Government Reports reveal covid jab failure. Sadly this will hardly be reported in the media. Health propaganda requires constant medical intervention, whereas good health doesn’t.

If anyone needs someone to talk to we meet every Sunday.

Stand in the Park Sundays 10.30am to 11.30am From 1st January 2023

Make friends & keep sane

Elms Field (near Everyman Cinema and play area)

Wokingham RG40 2FE