Why is the Government using taxpayers’ money to subsidise relatively well-off company car drivers more than £2,000 a month to slum it in £70,000 electric cars?

I don’t want to come across as some po-faced champion of the people. I drove a company car for years, exploiting every tax loophole known to man and I confess I’d no doubt be at the front of the queue to grab an EV tomorrow if anyone was foolish enough to employ me and throw in an EV as part of my salary package. In truth, I feel a bit like a member of the Magic Circle about to betray the secret of exactly where the rabbit is hidden before it’s pulled from the hat. Except, in this case I’m going to explain just how much the rest of us are spending on cross subsidies to allow company car driving executives to burnish their personal green credentials as they swan around in £70,000 EVs.

Let’s suppose I was employed and that my current company car was a £70,000 diesel powered BMW and on October 1st I switched it for a £70,000 BMW EV. Company car tax rates are complex and vary from car to car, but typically I might expect to have been paying £9,800 in tax per year on the diesel BMW. By switching to the EV my tax bill would go down to £560. I’d be better off by £9,240 and HMRC’s tax take would be down by £9,240, which the rest of you would need to make up.

I know lots of people who have an EV. I don’t know any who don’t like them; no one I’ve come across would swap back to an internal combustion engine car. Why are we subsidising them?

But the subsidies don’t stop there.

Let’s assume the £70,000 diesel BMW achieves 40mpg and that it covers 18,000 miles per year. Let’s also assume that diesel costs £1.85 per litre. Over the year I’d spend £3,785 on diesel of which £1,083 would be excise duty and £631 would be VAT. Add them together and we get a total of £1,714 collected in tax.

Adding the company car tax of £9,800 to the fuel tax of £1,714 we get an £11,514 contribution to the exchequer. Divide that by the 18,000 miles driven and we can see that the diesel BMW was contributing 64p per mile driven to the country’s tax take.

Of course, the exchequer still needs that £11,514 contribution. If the car driver stops coughing up it simply falls to other taxpayers to make good the shortfall. The taxpayer goes from having a positive contribution of £11,514 to losing that and yet still having to dig deeper into his or her pockets to replace it; the difference between the two situations is £23,028. But as I’m about to take delivery of my new, stunning looking EV maybe the tax I’ll contribute for the benefit of driving that beauty will go some way to reducing that difference?

Let’s look at the picture after October 1st when my new £70,000 EV turns up. I’ll still drive 18,000 miles per year but this time those miles will be powered at the rate of about 4 miles per kWh, that’s a total of 4,500 kWhs.

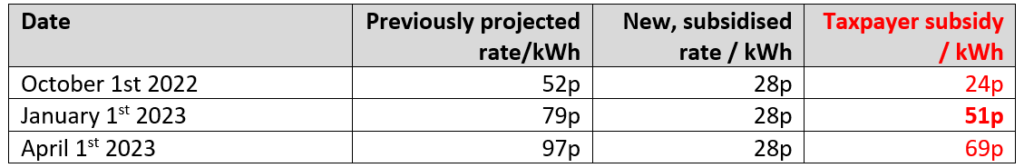

I wrote a piece in the Daily Sceptic in August about the relative cost of driving an EV in comparison to an internal combustion car. It assumed that the price per kWh of electricity would go up to 52p on October 1st 2022. That it would increase to 79p on January 1st 2023 and would further increase to 97p on April 1st 2023. We now know that this isn’t going to happen – though the Government’s actions haven’t cancelled the market forces driving up costs but simply deferred the costs by introducing a tax-funded subsidy. At the time of writing I haven’t yet seen what the ‘energy price guarantee’ will be in terms of the price per kWh but it looks like it’s going to be about the same as the current ‘energy price cap’ of 28p per kWh. This means that the taxpayer is subsidising each kWh at the following rates:

Let’s keep the maths simple and suppose that on average over the next 12 months the subsidy on the kWhs I charge the car with are at the January 1st 2023 rate, attracting a subsidy of 51p courtesy of the generous taxpayer. This means that I can expect that my electricity bill for the 4,500 kWhs I require to drive 18,000 miles will be subsidised by the rest of you to the tune of £2,295, or, if you prefer, by 12.75p per mile. If we look at the likely level of subsidy after next April, it will rise to 17.25p per mile.

Hang on, I can hear someone complaining at the back that I’m ignoring the tax I’ll pay on the electricity I charge the car with. You’re right, let’s add that to the mix. That’s 5% VAT, so on my 4,500 kWhs I’ll pay £63 of tax, or if you prefer, 0.35p per mile.

Let’s summarise. Driving my diesel 18,000 miles over the year I’d pay £11,514 in tax, working out at 64p per mile.

Driving my new EV I’d pay £560 in company car tax and £63 in VAT on the electricity, a total of £623 in tax or 3.4p per mile. But the taxpayer would, in addition, subsidise my kWh by £2,295. Let’s add those together: £623 – £2,295 = -£1,672, or looking at it another way, for each mile I drive the taxpayer contributes 9.3p.

Now let’s just look at the difference between me switching from my diesel to an EV. The taxpayer loses my prior contribution of £11,514, which the taxpayer has to make up, so that’s £23,028 in the swing going from a positive £11,514 to a negative £11,514 per year. In addition, the EV costs the taxpayer an additional £1,672; this gives us a staggering difference of £23,028 + £1,672 = £24,700. This converts into £1.37 per mile. That’s right, the loss to the taxpayer is £1.37 for every mile I drive my EV in comparison to every mile I would have driven my diesel.

In 2021, 190,727 electric vehicles were sold, accounting for some 11.6% of all new cars. More EVs were registered last year than over the previous five years combined. The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) commenting on the figures said: “Two-thirds of all new electric cars bought in the U.K. are purchased by businesses, rather than private buyers. The growth in the electric car market is being driven by the corporate sector.” No great surprise there on these figures.

I wouldn’t mind so much if it wasn’t for the self-righteous virtue-signalling that goes along with EV ownership. Just about everyone I know who drives some huge EV thinks they’re saving the planet, but surely, if it was planet saving they were primarily interested in, they’d have kept their old car going for another 100,000 miles or they’d have downsized to a basic car doing 80mpg. The figures I’ve seen claim an EV creates only 60% of the carbon footprint of an equivalent petrol or diesel car (though some analysts have suggested EVs actually emit more CO2 over their lifetime), but why compare to the equivalent car? If a diesel or petrol car achieved 80mpg or 90mpg, wouldn’t that be no worse for the environment than a 2.5 tonne all electric Land Rover? What’s more, it could be produced at a fraction of the cost.

Presently, the main people who can afford an EV are the relatively wealthy or the company car driver. The upfront cost of a new EV puts them out of reach of most people. But once these relatively wealthy people get hold of one it’s the rest of us who pay for it. The figures above look at the extreme case of the company car driver, but even the private buyer for whom there’s no company car tax benefit would see a huge saving. Let’s take for example a person driving a 12 year-old diesel doing 10,000 miles per year in a car doing 40mpg. He’d buy 1,137 litres of diesel costing him £2,103 at £1.85 per litre. This would contribute £602 in excise duty and £350 in VAT, a total of £952 in tax. Do the same mileage in an EV achieving 4 miles per kWh and the 2,500kWh used will raise £35 in VAT – but that electricity is subsidised by 51p × 2,500kWh = £1,275. Subtract £35 from £1,275 and we get a net cost to the taxpayer of £1,240 or 12.4p per mile. Again, looking at the difference, HMRC goes from receiving £952 to shelling out £1,240, a difference of £2,192 which has to be made up by the rest of us.

The table below looks at the difference in the tax for the fuel/kWh costs of EVs and cars with internal combustion engines. In each case the difference is the amount the taxpayer has to find to restore the tax take whenever a conventional car is replaced by an EV. I’ve ignored various other subsidies for EVs such as car tax to keep it relatively simple, but feel free to add your own list.

Virtue-signalling comes at a cost, but it’s a cost those of us who are being signalled at pay rather than the person doing the signalling. Shades of Marie Antoinette? How long before the driver of the 12 year-old diesel starts feeling resentful of the tax he’s paying to keep the £70,000 EV on the road?

Maybe we should look at lifetime environmental costs of all vehicles. If a sub 1 tonne, 90mpg diesel has a lower lifetime carbon footprint than a 2.5 tonne EV, why is the driver subsidising the EV?

Clearly, the taxpayer has pump-primed the market. Isn’t it time we throttled back a bit?

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.